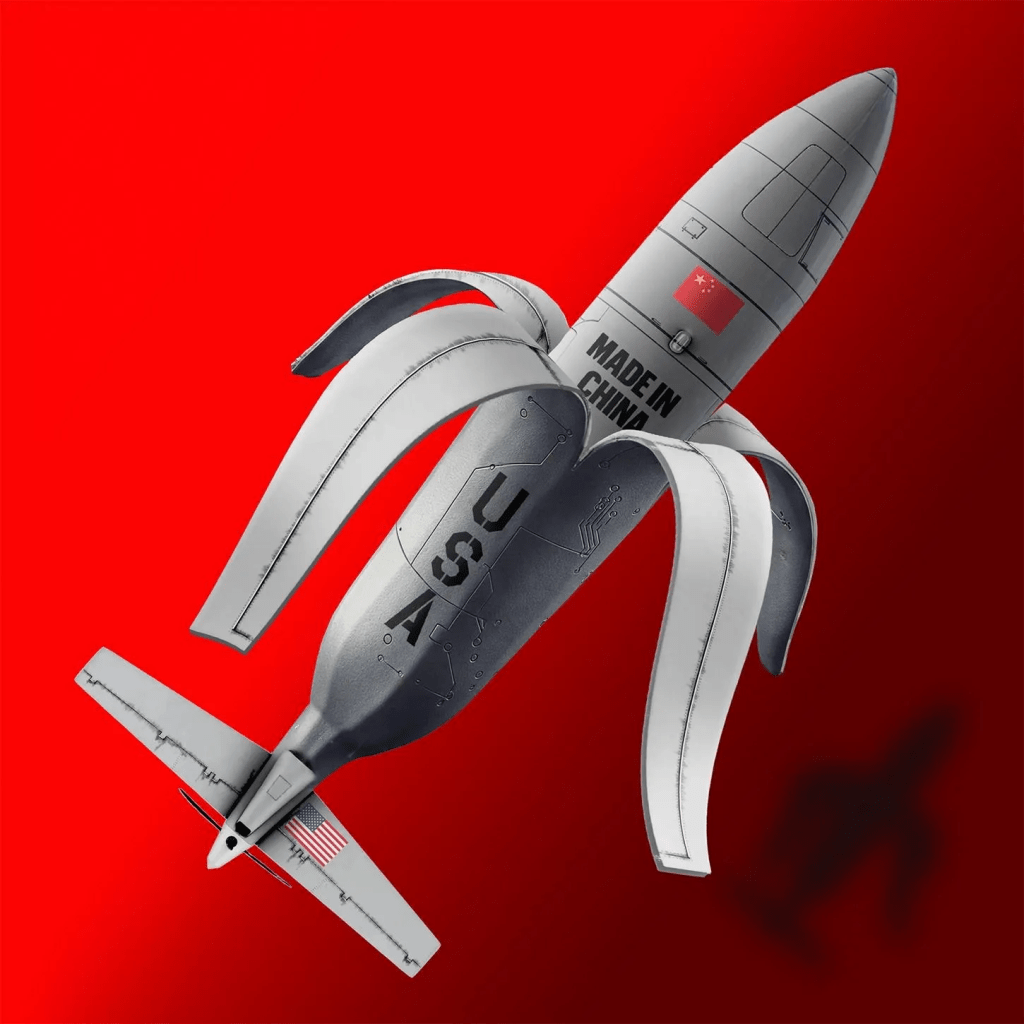

Pentagon leaders are calling for thousands of drones to prepare for war in the Pacific. But as Trump’s tariffs escalate tensions with China, they face an uncomfortable reality: Silicon Valley’s drone companies are addicted to Chinese components.

Itwas the day after Mach Industries published a slick promotional video for Viper, its new military strike drone, and CEO Ethan Thornton had a problem.

A few eagle-eyed viewers of the video, which Thornton had posted to social media proclaiming “Show, don’t tell,” had noticed that the drone used an engine with an uncanny resemblance to one made by a Chinese manufacturer. He’d vehemently denied that there were Chinese components in any of the company’s drones. But now Palmer Luckey, CEO of defense tech giant Anduril, had asked him a question with far less wiggle room to answer: “What about the airframe in the video?”

Backed into a corner, Thornton conceded on X: “We feel comfortable blowing up Chinese components for testing purposes, Palmer,” he replied, confirming the engine’s country of origin. (Thornton told Forbes “all final production units ship without Chinese components”; Anduril and Luckey declined to comment on the exchange.)

The conflict in Ukraine, rising tensions over Taiwan and the dominance of Chinese drone companies like market leader DJI have underscored the need for the U.S. military to source cheap and mass-produced drones from American and allied companies. But Thornton’s exchange highlighted an open secret in Silicon Valley: most drone companies answering the Trump administration’s America First mandate have a “Made in China” parts problem.

China currently controls close to 90 percent of the global commercial drone market, and manufactures most of the key hardware used to build them – airframes, batteries, radios, cameras and screens, according to market research firm Drone Industry Insights UG. Because of its longstanding reliance on these parts, the U.S. is years behind building the manufacturing infrastructure that could come close to rivaling China’s. “We are almost completely reliant on our major adversary for them, and our ability to make them,” said Josh Steinman, who previously oversaw supply chain security at the National Security Council.

It’s a reality that seems almost impossible to escape. When Vice President J.D. Vance attended a U.S. Marines drone demonstration for a photo opportunity at Quantico last month, pictures showed him wearing Chinese-made drone display goggles. (Major Hector Infante, who oversees training at Quantico, told Forbes the goggles “were not military-issued” and insisted they were provided “solely for viewing purposes”; the White House did not respond.)

US Vice President JD Vance wears a Chinese-made Skyzone headset during a tour of the Marine Corps Base in Quantico, VA.

AFP via Getty Images

This addiction to Chinese parts has set off alarm bells among military officials. Several American drone companies with Pentagon contracts — including Skydio, one of the largest — are scrambling to rebuild their supply chains after Chinese sanctions cut off access to suppliers. “China could shut [the drone industry] down globally for a year,” Trent Emeneker, who leads a team at the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit that approves drones for military use, told Forbes. “It’s a national security issue, not just for the United States, but for the global West.”

Some drone companies told Forbes the Pentagon’s bureaucracy has stunted the American industry’s growth. But the presence of Chinese parts has dulled Pentagon enthusiasm to adopt them at scale. For example, military purchases from Orqa, a drone company that pitched itself as “DJI of the West,” were halted after allegedly banned Chinese components were found in its products. “Most of the western drone companies still rely on Chinese components,” Orqa’s CEO Srdjan Kovacevic told Forbes. (He said Orqa has moved its manufacturing inhouse.)

It’s the kind of stranglehold that President Donald Trump’s tariffs are seemingly designed to break, theoretically encouraging American companies to reduce their reliance on cheaper foreign supply chains and build their own at home. But doing so will take years of research and development and significant investment. Meanwhile, China’s retaliatory tariffs are set to make components American drone makers rely on even more expensive; plans to redraft a new export system are already halting shipments of magnets, which are essential for drone motors.

“It’s easier to get sanctioned by China” than get Pentagon approval.

Andrew Cote, BRINC

But regulatory efforts to force the issue, by ending imports of all Chinese drones and parts, have faced strong opposition from Chinese manufacturers and American investors alike. Responding to a proposed Commerce Department measure that is considering banning or restricting Chinese-made drones and components, venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz — which has backed drone unicorns Anduril, Skydio and Shield AI — called for a more considered response with gradual restrictions on drone parts sales from China, while simultaneously allowing for U.S. companies to continue sourcing components from the country.

“Immediately removing all foreign adversary-based sources of supply for critical drone components would have a catastrophic effect on the American drone industry,” chief legal officer Jai Ramaswamy wrote in response to the Commerce Department last month (the firm declined to comment further).

Such a catastrophe might be what’s needed, national security experts say. “You are going to have to pull the bandaid off at some point,” said Steinman. “And either you are going to choose or [China] will.”

Troubled by China’s advances in drone tech, the Pentagon made drone acquisitions a major priority in 2023 and announced Replicator, an initiative to fast track production and deliver thousands of mass produced, cheap drones to counter China’s arsenal. But the initiative, which is expected to deliver its first drones by August, faces an uncertain future and is one of several that drone companies say don’t go far enough to spur adoption.

The primary on-ramp to drone contracts is the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), which maintains a so-called Blue List of drones that are approved for military use. The list, which is updated annually, is overseen by half a dozen employees who test hundreds of products to ensure they are free of Chinese components banned under the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), like cameras, flight controllers, radios and ground control systems — mostly components that transmit a signal and could be tampered with.

Companies big (Anduril) and small (Neros) have been included on the Blue List. But some drone manufacturers say it has become another bottleneck that stifles the industry. This year, just 23 companies were approved out of more than 300 submissions. San Antonio-based Darkhive was among the companies expecting to be included. After waiting for months, it learned its quadcopters hadn’t been approved when DIU issued a press release announcing the list in February. “There was no follow up apart from, ‘try again next year,’” CEO John Goodson told Forbes. (Darkhive maintains several Pentagon contracts through other mechanisms.)

Another company, BRINC, which has more than 700 law enforcement and public safety customers, and this month announced a $75 million funding round led by Index Ventures, was sanctioned by China last year after it attended a sales trip to Taiwan organized by the U.S. government. It didn’t make the Blue List either, and has now shifted away from its military business to focus on public safety contracts. “It’s easier to get sanctioned by the [People’s Republic of China] than it is to get on the Blue List,” said Andrew Cote, BRINC’s head of strategy and growth.

In December, the Pentagon halted use of drones sold by Croatia-based Orqa — which pitched itself as a Replicator solution and a “one-stop shop” for China-free components — after DIU discovered radio modules that were made in China and allegedly ran afoul of NDAA requirements, according to the company and multiple sources familiar with the matter. In addition, DIU learned that Orqa had acquired a China-based company in 2022.

“Until DJI is entirely banned, there’s not enough market to stand up a U.S. industrial base.”

Nathan Ecelbarger, U.S. National Drone Association

In response to questions, Orqa CEO Kovacevic acknowledged the modules were assembled in China, but claimed the underlying chips were made in Taiwan and Europe, and disputed that they were critical components; he said the company now makes its own modules. As for the China-based subsidiary, he claimed its operations were moved to Europe after the acquisition — except for one product unrelated to drones that is still manufactured in China.

Orqa had all of its submissions to the Blue List rejected. “What we previously thought were transparent rules, are obviously subject to very creative interpretations,” Kovacevic said. “There’s no transparency whatsoever to the process.”

The DIU’s Emeneker, who oversees the Blue List, isn’t having it. “Companies don’t get to decide what is and is not legal under the law,” he noted. He added that the results of the recent list refresh were made in accordance with law. “There are always edge cases and hard decisions to make,” he said. “But the process was standardized and designed to provide the best options to the warfighter.”

The Pentagon bans on Chinese components don’t extend to parts like airframes, engines and batteries, but relying on them can still be risky. In October, America got a peek at what a worst case scenario might look like when China sanctioned military contractor Skydio, cutting off the battery supply for America’s largest small drone maker, which has raised more than $850 million from investors like Andreessen Horowitz and Accel. The company said it wouldn’t be able to secure new suppliers until this spring, and would be forced to ration batteries.

“If there was ever any doubt, this action makes clear that the Chinese government will use supply chains as a weapon to advance their interests over ours,” Skydio said in a statement at the time. Six months later, the company has yet to announce a new supplier; it did not respond to a request for comment.

More than a dozen other drone companies vying for Pentagon contracts — including Anduril, Shield AI, Firestorm, CyberLux and Neros — have now been sanctioned by China. Some say it hasn’t impacted their operations. Lily Hinz, a spokesperson for Shield AI, said the company doesn’t use Chinese parts, and isn’t “feeling the impact” of the sanctions. Dan Magy, the CEO of Firestorm, said his company’s drones don’t contain Chinese parts, and called the sanctions “a badge of honor.” Anduril spokesperson Shannon Prior said the sanctions had “no effect on our business” and that the company had eliminated all “direct spend from China.”

But other drone makers have had to make changes. CyberLux CEO Mark Schmidt told Forbes his company was “pro-actively shifting away from Chinese components…and scaling its North American suppliers on the production of critical parts.” He declined to comment on the related costs and timeline.

Even California-based Neros, which designs and manufactures most of the critical parts for its $2,000 drones in-house, felt some pain from the December sanctions. Flush with a $35 million funding round backed by Sequoia, the company still relies on some Chinese parts. “Getting these components has been more challenging,” said CTO Olaf Hichwa. “But this is a good forcing function to become completely free of Chinese parts.”

Military leaders, national security experts and the drone industry all seem to agree on one thing: building a China-free supply of drones relies on expelling DJI from the U.S. The Shenzhen-based company, which became the world’s largest drone maker thanks to heavy subsidies from the Chinese government and funding from American venture capital firms Accel Partners, Kleiner Perkins and the former China-based arm of Sequoia, is the most ubiquitous drone seller in America, and one of the largest suppliers of drones to farmers and police departments.

“Until DJI is entirely banned, there’s not enough market to stand up a U.S. industrial base,” said Nathan Ecelbarger, chairman of the U.S. National Drone Association, which aims to speed up military adoption of drones.

But DJI has so far mounted a successful campaign to dodge efforts to ban its drones. It has protested the proposed Commerce Department rule to ban imports of Chinese drones and parts, calling it a move that would “significantly harm a number of U.S. stakeholders.” In October, it sued the Defense Department insisting it is not a national security threat, and it lobbied against a legislative measure that would have banned its products from entering the U.S., disclosures show. “DJI has been unfairly targeted due to its national origins,” the company said in a statement to Forbes.

In December, the legislative ban on DJI’s products was dropped from the annual military spending bill. DJI was free to continue shipping. In a statement at the time, the company thanked those who had supported its efforts to kill the ban — top among them, its American customers. “Your support made a real difference,” DJI said. “Congressional offices paid attention and listened to what you had to say.”