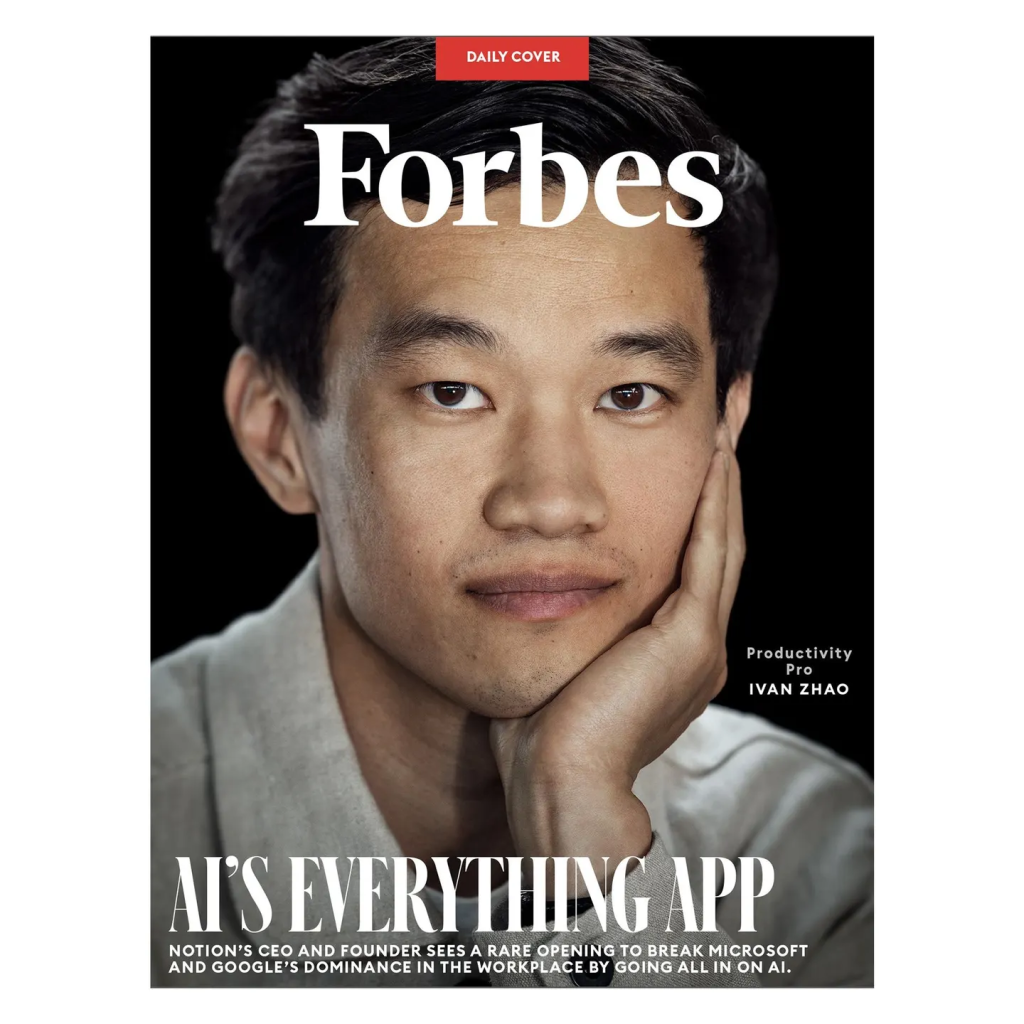

Notion co-founder Ivan Zhao captivated Silicon Valley investors and everyday consumers alike with a sleek productivity app that went so viral its servers crashed. Now, the profitable startup’s CEO sees a rare opening to break Microsoft and Google’s dominance in the workplace by going early and aggressive on AI.

Ivan Zhao had started Notion based on the idea that you should be able to do as much with a word processor as you can with a blank piece of paper.

Josh Kopelman, frequent Midas Lister and cofounder of First Round Capital, was so impressed by Zhao’s unusual pitch, which involved a lengthy digression into the origins of paper, he wrote the biggest check in the $2 million seed round in 2013.

“I remember walking out and thinking, ‘This is different from any founder pitch I’ve ever taken,’ ” Kopelman says. “There was no screenshot, no mockup. It was very conceptual, but I felt like I understood at the highest level what he wanted to do.”

But Kopelman was in the minority. Two years later, people didn’t understand Notion, the software editor Zhao had built, and he hadn’t figured out a compelling way to explain it.

Few saw a need for a tool to design personalized computer programs. When he saw First Round employees using Notion, it seemed to Zhao that they were doing it “out of pity,” he recalls.

“The software wasn’t good enough yet,” he admits. “You know you can get better. You know what better feels like. But you don’t quite know how to get there.”

In a last-ditch attempt to save the company, Zhao and cofounder Simon Last laid off all their employees, sublet their San Francisco office and moved to Kyoto, Japan, to cut costs. A $150,000 emergency loan from Zhao’s mother gave them enough time to reboot with “Notion 1.0.”

The software editor was still there, but now Notion looked like a productivity tool on the surface—a minimalist twist on Google Docs that also let you easily make wikis and manage your to-do lists. In August 2016, they released it on app discovery site Product Hunt.

It was the site’s most popular product of the day, then week, then month. Within weeks, Notion, which is free but charges power users upward of $8 a month, was turning a profit and had become one of Silicon Valley’s hottest startups.

In October, Zhao and Last returned to San Francisco triumphant. Notion was spreading globally (80% of users are outside the U.S.) on word of mouth alone.

It hit its first million users in 2019.

Students liked it for making to-do lists and taking class notes. Design-minded entrepreneurs used it to replace the traditional pitch deck, and artists to show off their portfolios. “How I use Notion” tutorials flooded YouTube.

People needed those videos because while Notion is powerful, the customization options for something as simple as a to-do list can make it overwhelming.

One of the most popular is a relatively simple walkthrough of the software that shows how to get started using it “without losing your mind.” But it was precisely this level of customization that made Notion so useful for work.

Employees at DoorDash and Nike adopted it to manage projects or share notes. It caught on among some teams at McKinsey after a partner began using it at home to organize his pizza recipes.

Scott Belsky, Adobe’s chief product officer, used Notion to organize all his research and write the drafts to his bestselling book The Messy Middle. “In a wonderful way, Notion has collapsed the concept of a website and a document,” he says.

In January 2021, a handful of those “How I use Notion” videos went so viral on TikTok that the demand for downloads overwhelmed the company’s servers and Zhao was forced to pause all product development for six months to shore up the back end.

At the time, the app had 20 million users. Now it’s fast approaching 100 million, Zhao says.

By Forbes’ estimate, it made $250 million in revenue last year and remains profitable.

Throughout Notion’s viral rise, Zhao managed to retain an unusually high degree of control for a startup of this scale.

None of the venture capitalists who’ve put some $330 million into Notion have a seat on the board. With VCs lining up to give him money, Zhao has little reason to give them one. (He recently added his first outside board member, a financial auditor, in 2022.)

And Notion’s longtime profitability gave him added leverage to raise funds with minimal dilution.

Forbes estimates that the 37-year-old still owns at least 30% of the company, worth $1.5 billion, based on Notion’s $5 billion valuation on secondary markets. (Akshay Kothari, 37, who joined in 2018, and Last, 30, cofounders in title, likely own less because they joined the company after inception.)

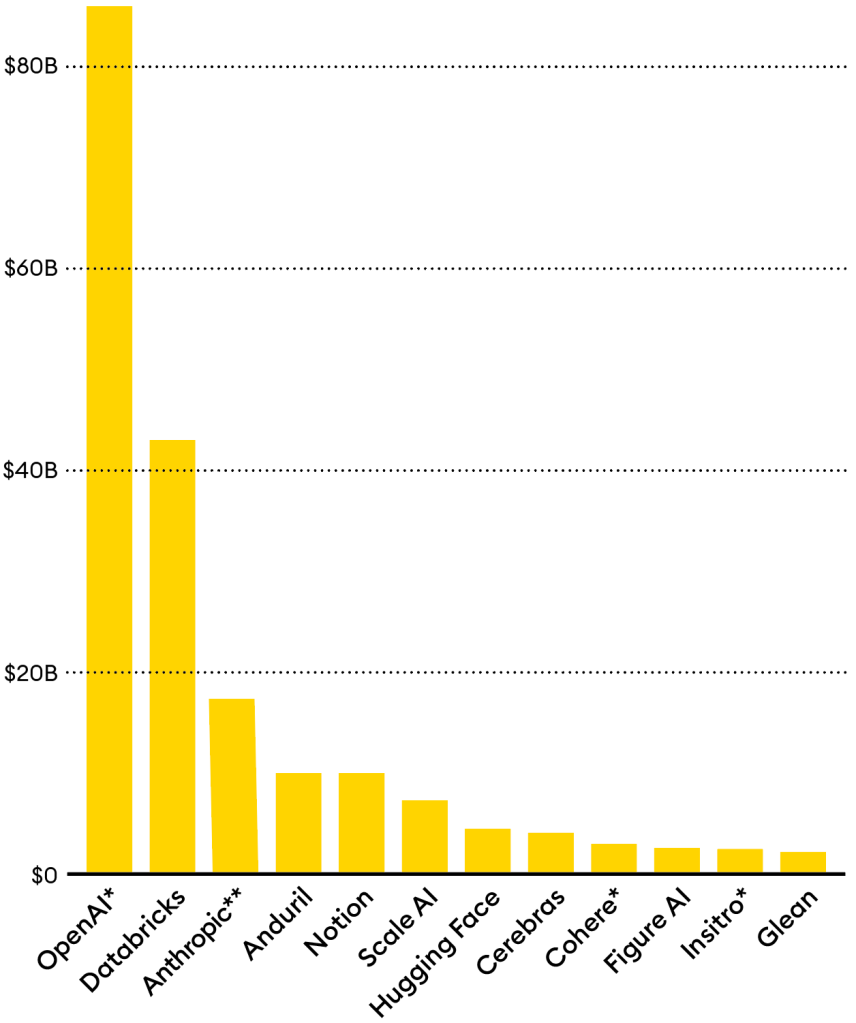

AI 50’s intelligent unicorns

In Silicon Valley, venture capitalists have driven the valuations of the hottest AI startups to lofty heights. Among them are OpenAI and Anthropic, whose models provide the bedrock for Notion’s AI product.

Notion’s last big release, which introduced spreadsheets and databases, was in 2018. Later this year, the company hopes to debut Notion 3.0.

Users got a preview when the company launched an artificial intelligence bot in November 2023 that can rapidly surface anything stored inside Notion, part of the company’s aggressive bet on generative AI that earned it a place on Forbes’ sixth annual AI 50 list.

No longer do Notion users need to remember where they put a particular piece of information. For instance, you can ask the bot, “What are the takeaways from the team meetings last week?” and it will pull them out from what it identifies as the most important documents.

Zhao says the bot is like an extension of his brain: “You have the freedom to forget.”

Layer in more automation—plus January’s launch of a calendar offering and perhaps an email client, thanks to a February acquisition—and Zhao’s ambition becomes clearer: to build Notion into an everything app for the office that might one day challenge the dominance of Microsoft and Google, which together control 99% of the $52 billion (2022 sales) productivity suite market, per Gartner.

“Our competitor is the entire industry,” he proclaims. “If you’re building Legos, are you competing with a toy airplane or toy car company? It’s both.”

“Notion is a manifestation of [Zhao’s] value system and his urge to create. That’s why he doesn’t want to sell the company. I can’t imagine he even wants to go public.”

Enterprise AI software could be a $1 trillion market opportunity over the next decade, according to Wedbush analyst Dan Ives. “It’s a yellow brick road of growth ahead,” he says, even without confronting Microsoft and Google head-on.

Zhao acknowledges this point, but he has ambitions of building something just as lasting. “The enterprise is a challenge, but if we just execute, we’ll get there,” he says.

Though Zhao studied cognitive science at the University of British Columbia (he immigrated to Canada with his mother from China when he was 17), he also considered a career in photography and got involved with the local hacking scene, where he learned web development.

When his friends asked him to design portfolio websites to display their photography, he thought they ought to be able to show their creativity just as easily on a computer as they could with a camera.

It gave him the idea for a flexible editor that would enable anyone to easily create a portfolio, a task tracker, a complex database—or anything else of their choosing.

After Zhao spent a year learning the inner workings of Silicon Valley at e-textbook startup Inkling, he began pitching Notion—even before he had a prototype.

His clarity of vision wowed angel investors, which included Kopelman, Facebook’s product chief Mike Vernal and Kothari, who invested $75,000 from a recent windfall selling his first startup to LinkedIn.

“He’s authentically offbeat,” says Inkling cofounder Matt MacInnis, who wrote Zhao his first check for $50,000. “He’s got a certain taste in how things should be.”

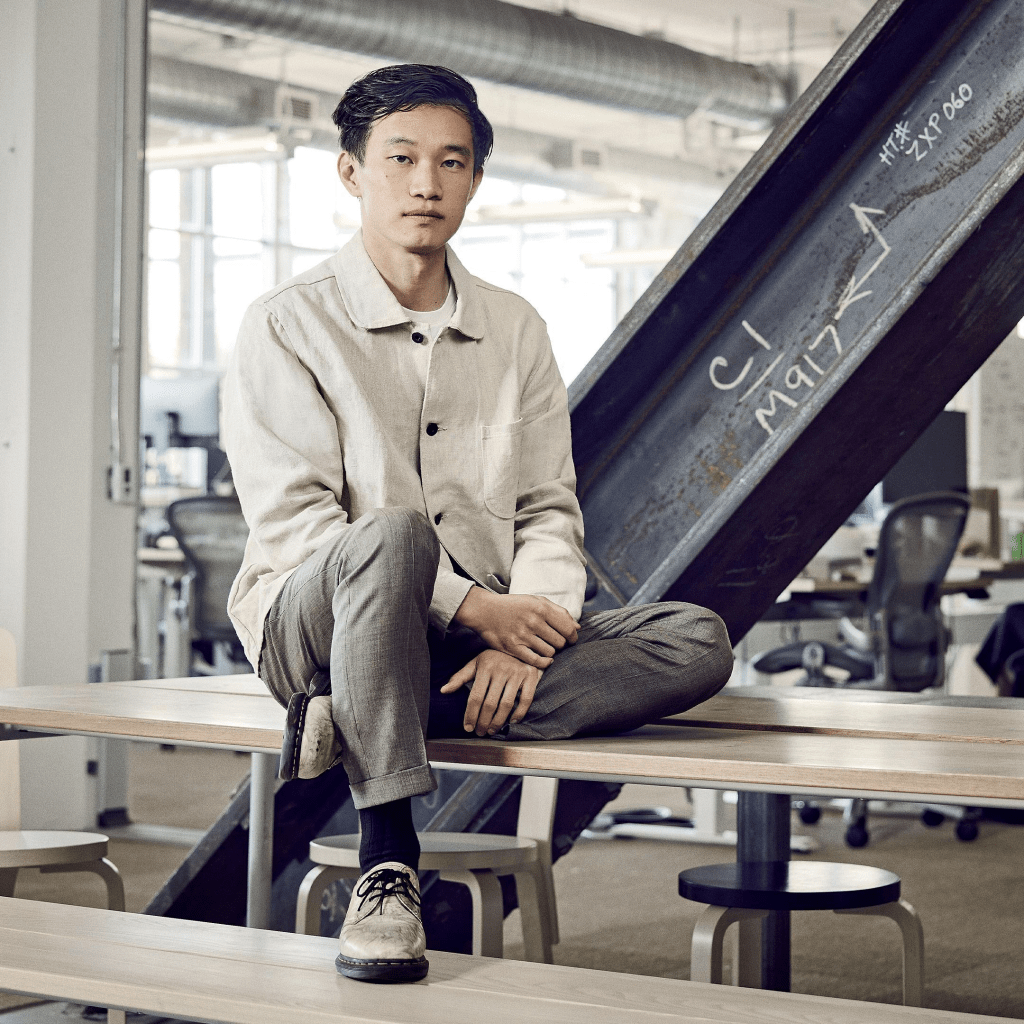

That included instituting a no-shoe policy and handpicking all the furniture as Notion moved from office to office in San Francisco’s Mission District.

In those early days, financial constraints meant he bought cheap Ikea tabletops and brought in a rug from home, but even then he refused to skimp on seating. His favorite is the Aalto stool, designed in 1933, which might look like any garden-variety wooden footrest yet retails for $400.

For Zhao, it exemplifies the simplicity and versatility he wants Notion to have.

People who know Zhao well say his new wealth and Notion’s success have hardly changed him.

He still picks out all the furniture for Notion’s office—recent additions include curvy Artek armchairs ($6,000 each) and the De Stijl art movement’s angular Red and Blue Chair (resales for about $3,000)—though he has had to compromise in some ways: Shoes are now allowed.

“Notion is a manifestation of his value system and his urge to create,” MacInnis says. “That’s why he doesn’t want to sell the company. I can’t imagine he even wants to go public.”

He was skeptical about raising money, too. Danny Rimer, a partner at Index Ventures, remembers first meeting him at a board meeting for Figma, where Zhao bluntly introduced himself by saying, “I’m trying to understand whether boards or investors make sense.”

His conclusion? They didn’t.

So he stopped taking meetings with investors. When Rimer’s then-colleague Sarah Cannon appeared at Notion’s office unannounced with tickets to a Marcel Duchamp exhibition after learning that the French artist was one of Zhao’s favourites, he was a no-show.

“The native form factor of AI products…will look very different from what we have today, and our deep conviction is that builders like Notion are the ones who will invent it.”

All of this gave Zhao something of an “anti-VC” reputation. He says it’s not true, but he attributes its roots to Shana Fisher, an early investor, who convinced him that his time would be better spent on development and hiring.

“If you’re patient, you will get the grand slam,” she told him.

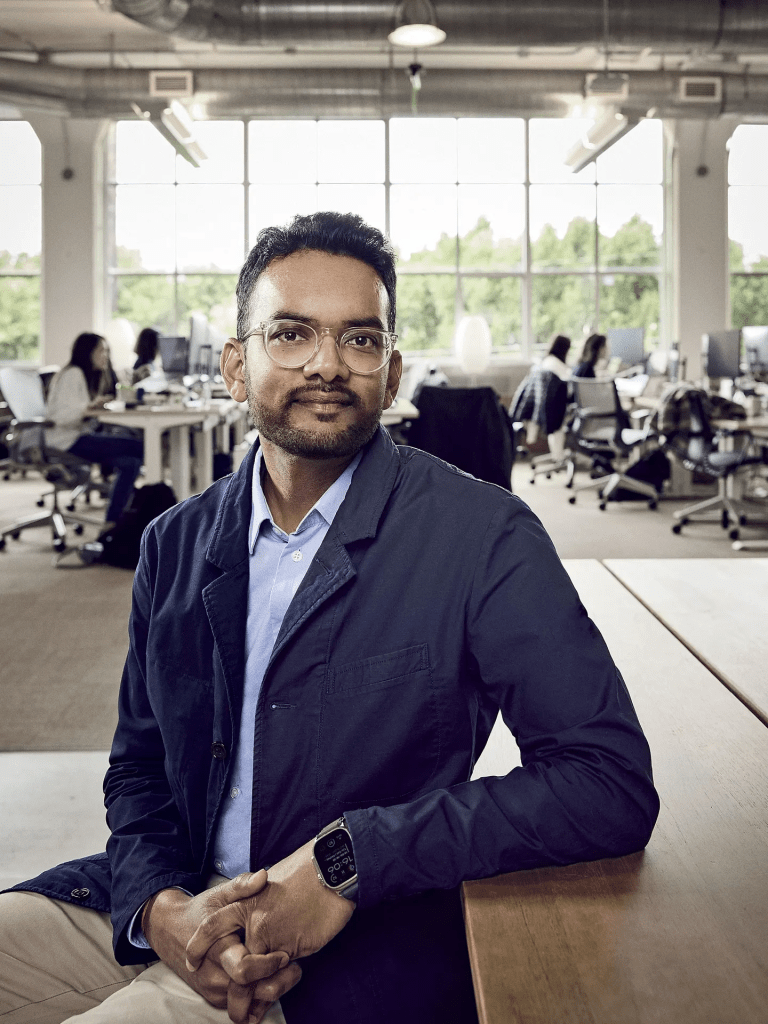

One of those hires was Kothari. During a routine investor update in 2018, Zhao surprised him with a job offer: chief operating officer.

Kothari was living in Bangalore, where he ran LinkedIn’s 1,000-person India operation and his wife was overseeing construction of their new house, but he was willing to relocate to California after a few days of playing with Notion’s new 2.0 product.

“I was actually convinced by the end of the week, but I had to spend a couple months convincing my wife,” he says. Zhao later gave him the cofounder title in recognition of his efforts launching the sales, recruiting and finance teams.

It took the uncertainty of the pandemic to convince Zhao he should raise rainy-day funds. But he still called the shots: no board seats, low dilution.

Index sprang to lead a $50 million investment at a $2 billion valuation in February 2020 within 36 hours of Zhao starting fundraising. It was a similar story in October 2021 when Notion raised $275 million from Coatue and Sequoia.

Zhao called Vernal, who had become a partner at Sequoia, on a Friday morning to offer the illustrious firm first dibs on investing $100 million—if they could decide that day.

The $10 billion valuation was “very painful,” admits partner Pat Grady, but within 30 minutes of reviewing the financials, Sequoia agreed.

“Not me, not another investor, not anybody is responsible for the success of this company. They are doing it themselves,” Fisher says. “That’s the art of this thing.”

During an October 2022 company offsite in Cancún, Last received an email from friends at OpenAI offering early access to an AI model known as GPT-4.

He and Zhao were so blown away that they skipped the team-bonding events and holed up in their hotel room for days until they scrapped together a bare-bones AI writing assistant.

When ChatGPT launched the next month, provoking a mad dash by businesses to integrate AI into their offerings, Notion was already out to market.

In 2023, the company followed up with a Q&A bot that can retrieve information stored within Notion. Its AI tools are built mostly atop GPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude and a few other open-source AI models.

Now, a year and a half into the generative AI boom, Notion is in pole position among productivity apps. The company charges an additional $8 monthly for access to the AI features.

Millions have tried it, and so far the business is faring “better than our highest hopes,” Zhao says.

But their rivals are among the biggest companies in tech—Google, which injected dozens of AI features into its work suite, and Microsoft, whose new collaboration app, Loop, looks eerily similar to Notion.

“I often tell Ivan, we may compete, but the number one thing we both compete with is the old set of tools,” says Shishir Mehrotra, a veteran of both Google and Microsoft who now runs Coda, one of the myriad smaller productivity companies also trying to make a dent in the duopoly.

No one knows how AI will evolve, but the winners of the next act might have to look beyond familiar interfaces like chat.

“The native form factor of AI products has yet to be invented,” says Olivier Godement, a product lead at OpenAI who has worked closely with Notion to integrate its AI. “It will look very different from what we have today, and our deep conviction is that builders like Notion are the ones who will invent it.”

Zhao has tried to keep Notion as lean as possible, and its word-of-mouth growth let him avoid hiring a big sales team. But those days are over.

The company now has 650 employees spread across offices in the U.S., Ireland, India, South Korea and Japan. Customers are increasingly businesses, not individuals, though many of them are smaller startups.

Zhao estimates half of Y Combinator runs on Notion, as do many rising stars on the AI 50, including Perplexity, Pika and Runway.

To get to the next level, Zhao is building out a sales team to target larger clients where usage is often limited to individual teams, like at McKinsey and OpenAI.

The bull case here for Notion is Atlassian, the $3.9 billion (2023 sales) software firm that became a work staple by first attracting small groups of users within larger organizations who loved using products like Jira.

“Notion is kind of similar,” says Sequoia’s Grady. “If they can make the teams happy, it’s kind of inevitable that they’ll end up with the whole thing.”

For Zhao, who wants Notion to be ubiquitous, ending up with the whole thing is the goal. To do that, he needs to make the software eminently flexible—a real everything app that can not only replace tools for work but also organize people’s lives.

That said, he recognizes his pitch to investors a decade ago of fully unseating incumbents like Microsoft and Google was a “romantic” notion—but only to an extent.

“The lawyers probably will use Microsoft Word until the end of time, but they might use Notion for other parts of their workflow,” he says.

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.