David Reilly worried that breaking up with Microsoft had thrown his Sydney-based quantum computing team’s future into peril… Then the phone started ringing.

Two Microsoft vice presidents turned up at the University of Sydney armed with carrots and a big stick.

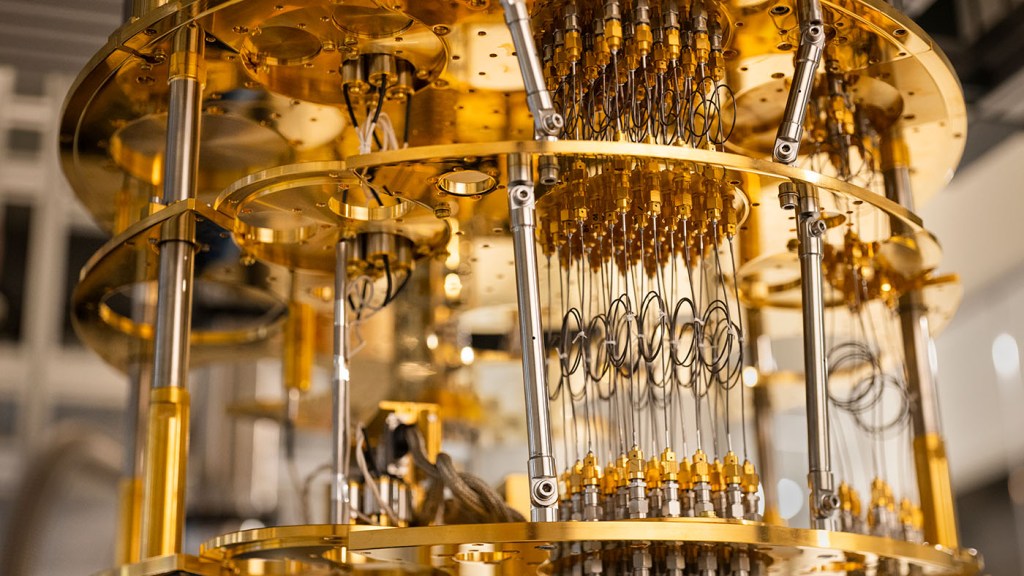

The good news was that they loved their Sydney team’s work figuring out how to connect quantum computers to classical computers. They liked it so much they wanted to throw more resources at it and bring it in-house. They wanted the entire team of 15 Microsoft employees based at the University of Sydney to move to Seattle.

The carrot was salaries large enough “to buy a house in Sydney without a mortgage” after a few years.

The stick was that the world’s second-largest company was shutting down the Australian lab – the Microsoft Quantum Sydney laboratory at Sydney Uni’s Nanoscience Hub – so if the team didn’t come over, their jobs would no longer exist.

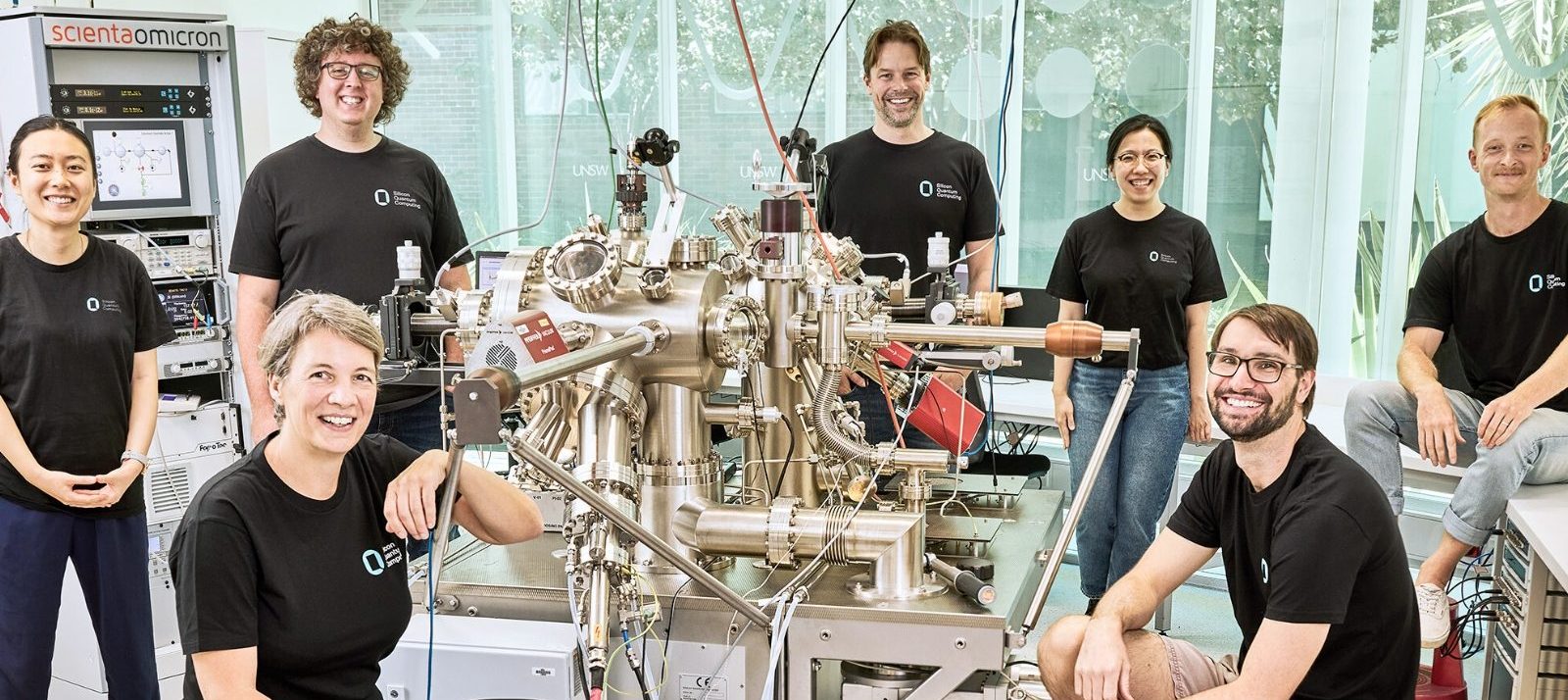

Microsoft Quantum Sydney was set up at the university’s $150-million Nanoscience Hub, to much fanfare, in 2017. Rather than building a quantum computer, the team headed by Professor David Reilly worked on creating the hardware that would allow a classical computer to control a quantum computer.

In 2021, the team announced a major breakthrough in solving the “input/output bottleneck” – one of multiple problems that need solving before a quantum computer can become a generally useful tool and open up quantum’s long-held theoretical promise of untold computing power.

The team had also made unpublished breakthroughs of commercial significance which had been kept under wraps, Reilly says. “It [the Microsoft relocation offer] was the result of the success we’ve had which we haven’t been public about.” And while Microsoft still owns that intellectual property, Reilly says the greater value is what the team members hold in their heads.

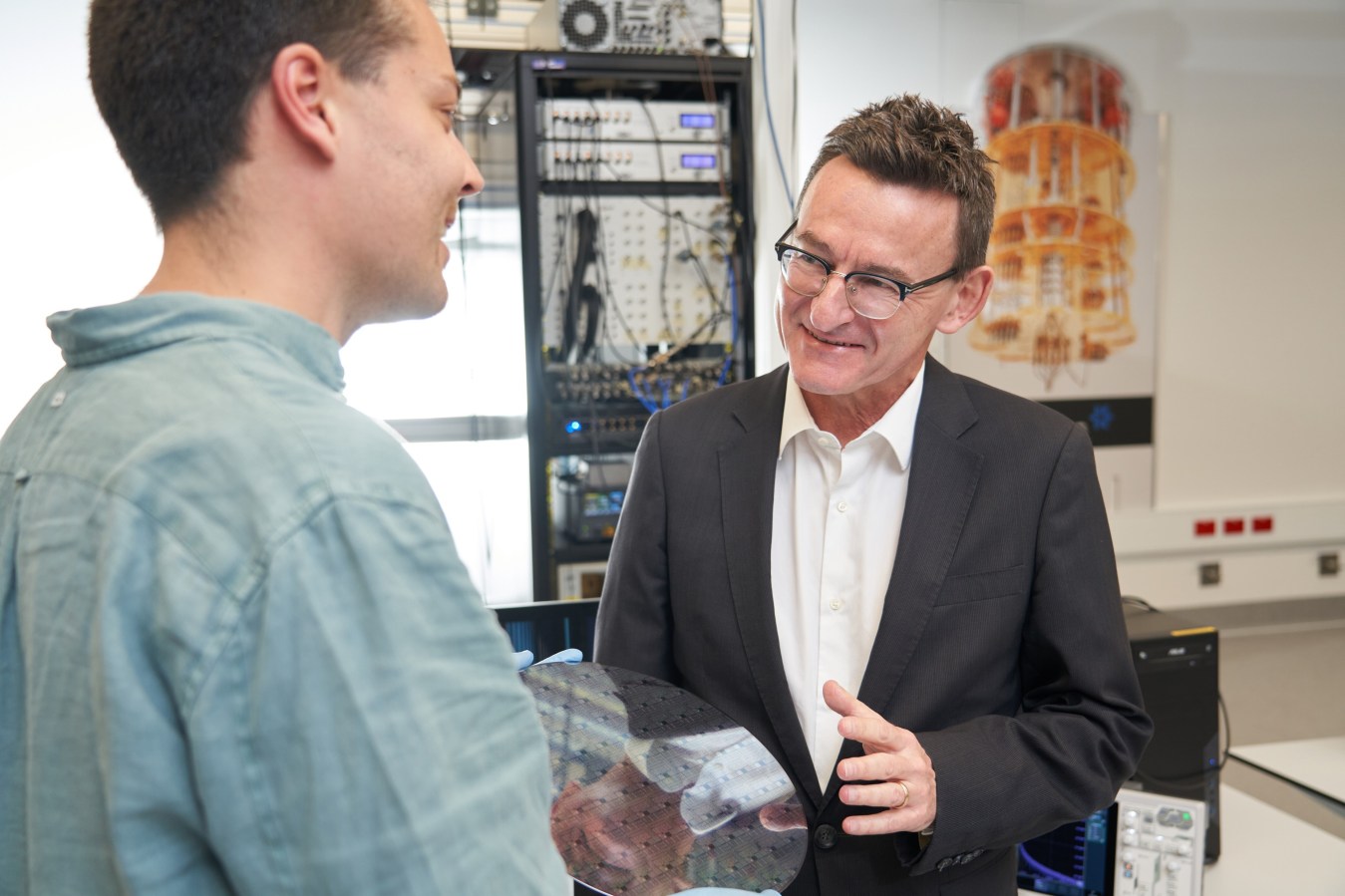

Reilly and his key collaborator, quantum engineer Tom Ohki, met with the Microsoft vice presidents, then with a university deputy vice chancellor who wanted to keep the team on campus.

“You’re not going to do anything great if you’re too comfortable.”

Tom Ohki, former Microsoft quantum scientist

They had limited time to decide, says Ohki. “We spent a lot of that time talking. You’re weighing the pros and cons. None of it is easy. But the fact there was support [from the university] – somebody who cared about the people and cared about keeping it here – showed we were on the right track.”

Reilly imagined that, if he took the offer, a perfectly comfortable life awaited him in Seattle, but he was haunted by the fear that one day he’d look back and wonder what they could have achieved if they’d done it their way. “Even though it’s hard to predict now, we feel that a decade from now we’re going to look back and say ‘That was a crazy time, a bold decision, but look at the impact we’ve had.’”

Ohki and Reilly met with their team of 15 and laid out their thought that they could do exactly what Microsoft wanted to do, but do it in Australia, maybe as a start-up, maybe with a foot still in academia, and sell their product to a multitude of other companies, including Microsoft.

“We didn’t want to pressure people,” says Reilly. “They needed to make an individual choice of what’s right for them and their families.”

“Just going around the room, we realised that everybody had the same perspective … Everybody was like ‘Let’s stick together and do something big.’”

The consensus was that they would have more impact separate from Microsoft, because they imagined working with many different teams attempting to build quantum computers and would not be chained to the success or failure of Microsoft’s effort. Quantum Insider identified 79 companies worldwide attempting to build a quantum computer, or part thereof.

“It was less ‘us against them’,” says Ohki, “and more, ‘What are the opportunities if we accelerate here in this ecosystem?’”

Agnostics

There was also a certain nationalism in their decision, even though Ohki – an American with an Australian wife – had only moved to Sydney during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I made Australia my home. My kids are Australian,” Ohki says. I do want to see how we can make it succeed and I think it’s a unique environment to do that. Not only because of the pool of talent, but the quantum ecosystem reminds me of the US a decade ago when (the quantum scene) was starting to take off. It’s a chance to jump on a ship that’s about to launch.

“I also think you’re not going to do anything great if you’re too comfortable.”

It is still unknown when a useful quantum computer might become operational. Or whether one will ever operate, and, crucially, what type of system might get there first, be it with semi conductors, or super conductors or light-based systems, as per PsiQuantum’s system, into which the Australian and Queensland governments have invested $940 million with the plan to have it finished by 2027.

But Ohki and Reilly imagine creating a product that is “qubit agnostic” – that it will work with whatever system gets there first.

“This could plug into PsiQuantum, Diraq, SQC, everything, and all of a sudden you have the whole Australian ecosystem benefitting.”

“Australia has efforts doing qubits and some efforts doing software,” says Reilly. “What’s missing is the thing that’s connecting them and that’s what we’ve been focused on for 25 years.”

But still Reilly worried that they’d chosen a very hard path. “When you sit down after the dust settles and try and figure out how you’re going to pay a mortgage, it really hits home.”

He was, however, confident that a lot of quantum companies around the world had no good solution to the problem that he and Ohki were solving. When news broke of their decision to break up with Microsoft, Reilly’s phone started ringing and confirmed the hypothesis.

“They reached out to us from all over the world saying, ‘What are you guys doing? Would you like to join our company?’ Small companies, big companies, government labs, the whole spectrum. There was a quick alignment.”

One of those callers was Reilly’s old PhD co-supervisor, Professor Andrew Dzurak, who founded quantum start-up Diraq, out of the University of New South Wales in 2022, and who has raised US$135 million from private and government sources.

“The former Microsoft team are definitely one of the world leaders in the development of classical cryo-CMOS chip design – and we have actually been collaborating with the team for some time,” says Dzurak. “In fact, we just posted a paper on the public arXiv which demonstrates the use of one of their cryo-CMOS controller chips to operate a Diraq two-qubit device.”

Reilly and Ohki have begun putting together a pitch deck to look at the potential of spinning out a start-up with venture capital, but say they have not decided what their new entity will look like.

Whatever it is, “it will be bigger and more ambitious than what we were doing with Microsoft,” says Reilly. “Our intent is to build something that has all the upside of academic university activity – blue-sky research, students, discovery – but then to also have a new company that will closely partner with the academic side to have the best of both worlds.”

In response to Forbes Australia‘s questions, Microsoft said in a statement: “We recently made the decision to close our quantum facility at the University of Sydney as part of an ongoing consolidation of our quantum engineering resources as we accelerate the move from research to productisation. The work that the team previously did in Sydney will move to the core team who are leading our quantum efforts globally.”

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter hereor become a member here.