OLEG VORNIK, a Russian kid from New Zealand, took American start-up DroneShield to Australia to make anti-drone defence systems that are now used all over the world, including the conflict in Ukraine.

DroneShield’s headquarters, high in a Sydney office tower, is a mess. As CEO Oleg Vornik gives a tour of the 23rd-floor defence tech HQ, the reason for the stacks of miscellaneous stuff lining the corridors becomes clear. He moves past the “drone guns” decorated with camo netting, past the software guys doing command and control – “basically, it’s Google Maps for drones and drone pilots, with little icons for where the drones are and little flags where the drone pilots are” – to an embedded defence team working on AI to detect “never seen before” threats; past the design team which creates every part of their drone defence systems; and on to the team doing final assembly.

The office gets messier with each new section.

DroneShield is using its Sydney CBD office as the final assembly plant for all the bits that arrive from a multitude of fabricators in Australia and the US. The biggest boxes and crates are finished products waiting to be shipped worldwide. “This is a DroneSentry-X”, says Vornik, pointing at a wooden crate containing a vehicle-mounted device capable of detecting and dropping unseen drones several kilometres away – and telling you where its operator is.

DroneShield is getting busy. It announced a $9.9-million deal with an unnamed government in July and, weeks later, a $33-million order from the US Government, more than doubling its previous year’s revenue with just two signatures. The share price has lifted about 50% since July 1.

“When we started eight years ago, there was no counter-drone industry. Drones were what you bought your child for Christmas. They were not a weapon.”

Oleg Vornik, DroneShield CEO

Vornik is negotiating for premises two-and-a-half times larger, he says. But location is difficult. “If you’re hiring a lot of bright young software engineers, you don’t want to be out in the sticks because they’ll not want to come to the office. So, you try to strike a balance between that and not having a big manufacturing operation in a high-rise office building.”

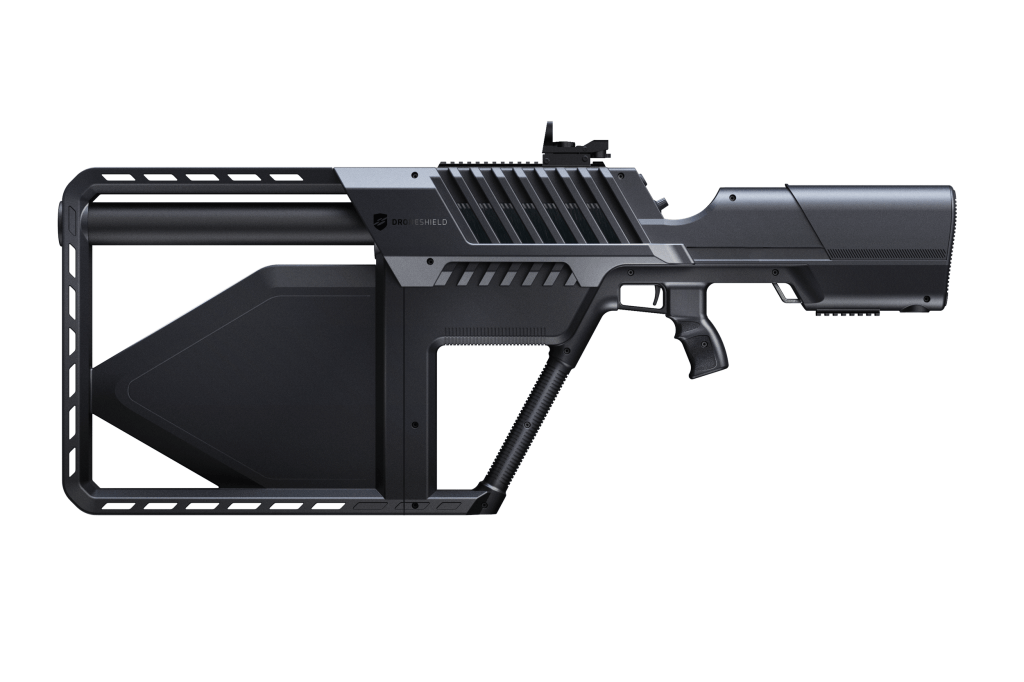

He picks up a DroneGun Tactical, which looks like a superhero’s alien slayer. There’s no need for it to even look like a gun, says Vornik. “But we believe end users want an emotional connection to the product.” And that’s why the DroneGun Tactical looks so cool, especially accompanied by sunglasses and a frown.

DroneShield was founded in 2014 by two former US military men, Brian Hearing and John Franklin, whose first idea had been to use sophisticated acoustics to detect that dreaded nighttime raider, the mosquito, and shoot it down with lasers. “They were shooting these movies in slow motion,” says Vornik. “Mosquitoes spiralling down with smoke coming out of them, like a World War II movie.”

Alas, the idea did not catch on. Hearing and Franklin pivoted to drones using radio frequency and the same highly sensitive acoustics with software to distinguish aeroplanes and cicadas from unwanted unmanned aircraft – too small and too plastic to be picked up by radar – then dropping them with jamming technologies.

Their first big sale was to the Boston Marathon, which, rocked by a bomb attack in 2013, had decided to cover all of its bases. A private equity fund read about it and bought the company. They wanted to list it in Australia because the ASX was branding itself as an enabler of small, innovative companies, says Vornik.

The fund needed somebody on board who knew how to list companies in Australia, and they chose Vornik. “Even though my defence and security experience was non-existent,” he says.

Vornik was born in Russia, but his family left in 1997 when he was 15, during the post-Soviet chaos. They moved to New Zealand under a skilled migration program. His single mother, a doctor, was not able to practice, so she requalified as a natural medicine practitioner.

“We were in a bad situation financially in the beginning – in council housing as I went through high school and university.” But the rigorous, almost brutal, Soviet-style of teaching maths put him in front of his classmates, so he studied that at university and got a job as a high-frequency hedge-fund trader in Auckland. After two years of working from 6 pm to 6 am, he went into investment banking with ABN Amro. Then he moved to Sydney, working for Brookfield Australia, Deutsche Bank and Royal Bank of Canada, where he worked on taking companies public. “I was about ten years in as a banker and felt I’d overstayed my welcome. Past a certain age, you need to be a particular type to thrive in that environment, and I wasn’t that person,” he says.

He got a call from DroneShield, and he jumped. “We didn’t have much money, so I was paid $100 a day until we listed.” The company raised about $7 million in the listing. “As soon as it was done, I packed my bags and moved to Virginia for two years to teach myself the defence trade at our office there,” he says. It was the only place to be – with CIA headquarters, the Pentagon, and a string of military bases nearby.

“I realised that a kid with a Russian name living in Australia would not be doing great business selling to the US. So, I switched my focus from sales to building a team.” Finding the right people proved difficult. And he twice had to completely turn over the staff.

“Once you set the wrong culture, it’s hard to change it incrementally. You need to uproot the whole thing and start again. Thankfully, US employment laws are more employer-friendly than in Australia. We had to acknowledge that we had made a mistake and hired the wrong people.”

What made him think he could get it right the third time?

“I had no choice. The US market opportunity was incredible, and I knew I had to keep trying until I got it right. I didn’t want to live in Virginia forever and needed to establish the team before I left.

“It often starts with one person. We hired Matt McCrann [US CEO], who is ex-US Navy intelligence. We got lucky with him. Other people started building around him. You can just tell by the level of engagement. Sales can take a couple of years, but just seeing what type of government trials you get invited to, small purchases. Those guys were doing great from the get-go. I could go back to Sydney and focus on scaling.”

Houthi rebels from Yemen were the first to start using drones as weapons on any scale, giving the company its first boost. Since 2015, the rebels have used drones to attack Saudi bases and oil pipelines – including one attack in which they took out Patriot missile radars, disabling the missiles so they could fire rockets into the kingdom.

Starting with small orders, DroneShield jumped through the hoops to get into the US military. “The thing about selling to government is it can take a couple of years from first hello to first sale, but once you have the relationship, it’s painful for them to move to someone else. So long as they’re happy with what you’re providing, it’s very sticky. Repeat orders are fast because you’re in the system with the right certifications,” Vornik says.

DroneShield says it’s now selling in about 100 countries, with distributors in about 30 of them. Being purely defensive, the product has less moral ambiguity than drone manufacturers who have no control over how their product is used once it is sold.

The company raised $17 million in 2021, led by Phil King at Regal Funds Management. Staff numbers jumped to 65. Last year, they looked for $3 million more with a share purchase plan for existing shareholders, but got orders for $29 million. They decided to keep the extra money and used it to take on 20 more staff, build inventory and upgrade their testing range in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney.

When the US Government put in the $33-million order in July, the company was ready. The order involves hundreds of units, each containing about 200 parts from 30 suppliers. “We ran into an issue a few years ago where a product worth $50,000 was waiting on one $20 knob. The whole production was halted for a month. After that, we bought thousands of those knobs – hence, all the boxes lying around. It’s like conducting an orchestra where no one thing can fall behind.”

The Ukraine war has transformed the business, with YouTube demonstrating how dangerous a drone can be. DroneShield has been in Ukraine since the first days of the conflict. But it is not selling to the Ukraine military. An unnamed European government is buying and donating units.

Vornik says that at the beginning of the war, there was some awkwardness with him being Russian. “Putin helped me in a strange way,” he says. “Our products were so successful that he put DroneShield and four employees – me, our CTO, one of our senior sales guys and one of our senior engineers – on the sanctions list. It’s a badge of honour.”

Vornik received up to 30 emails a week from Ukrainian soldiers and their families asking for more, he says. “Sometimes, they’re saying they’re hiding in a building, and there’s a Russian drone hovering outside. Sometimes, they say how safe it makes them feel.”

Another reason for shifting the company to Australia was the tax incentives. “Unlike anywhere else in the world, here we get 43 cents back on every dollar spent on R&D in cash. This year we’ll claim more than $2 million on our expenditure. Next year will be even bigger,” he says.

The quality of top talent in Australia is “no worse than in the US”, but there’s less competition for it, Vornik says. “We don’t have Tesla, Amazon and SpaceX. Here, we’re a cool kid on the block, but in the US, there are a lot more cool kids.”

DroneShield doesn’t tend to hire engineers with a military background. “Traditionally, this sector operates on very long horizons at low speed,” Vornik says. “We draw on a lot of people who were designing technologies in the medical products industry. Medical and defence have interesting similarities. In many other industries, it’s okay for the product to have an error. It’s okay for a laptop to reboot. You just wait for it. Military and medical are two areas where it must work every time, so that mindset is important.”

But Vornik has the same perfectionism for his engineers as he demanded from his US sales team. “When somebody has been in the top 10% at another company, they’ll come to DroneShield and be average, which is a stress for a lot of newcomers. When you hire people who aren’t performing, you have to move them on. If not, you are creating cancer within the company where somebody says, ‘I’m working my arse off. Why is this guy next to me just coasting and not producing much?’”

Last year, DroneShield launched a software-as-a-service (SAAS) subscription model.

“Customers are not locked into quarterly updates, but we highly recommend it as new drones come out and you want the latest firmware on our AI,” he says. “You’re not an AI company if you’re not sitting on a treasure trove of data. Where the customer allows us, we collect data from the field, get it back here, and use it for our product development.”

FULLY WEAPONISED

DroneGun Tactical: 7kg anti-drone device that only needs to be pointed vaguely towards an enemy drone several (exact ranges are secret) kilometres away to disable it with complex jamming technology.

DroneGun Mk4: 3kg pistol-grip drone gun with slightly less range than the Tactical.

RfPatrol: Walkie-talkie-sized wearable that alerts the user – and headquarters – to nearby drones.

DroneSentry-X: Vehicle-mounted device that passively listens for drones with no radio missions. Upon detection, it switches to their radio frequency and jams them, dropping them automatically or manually while providing map displays of drones and their pilots.

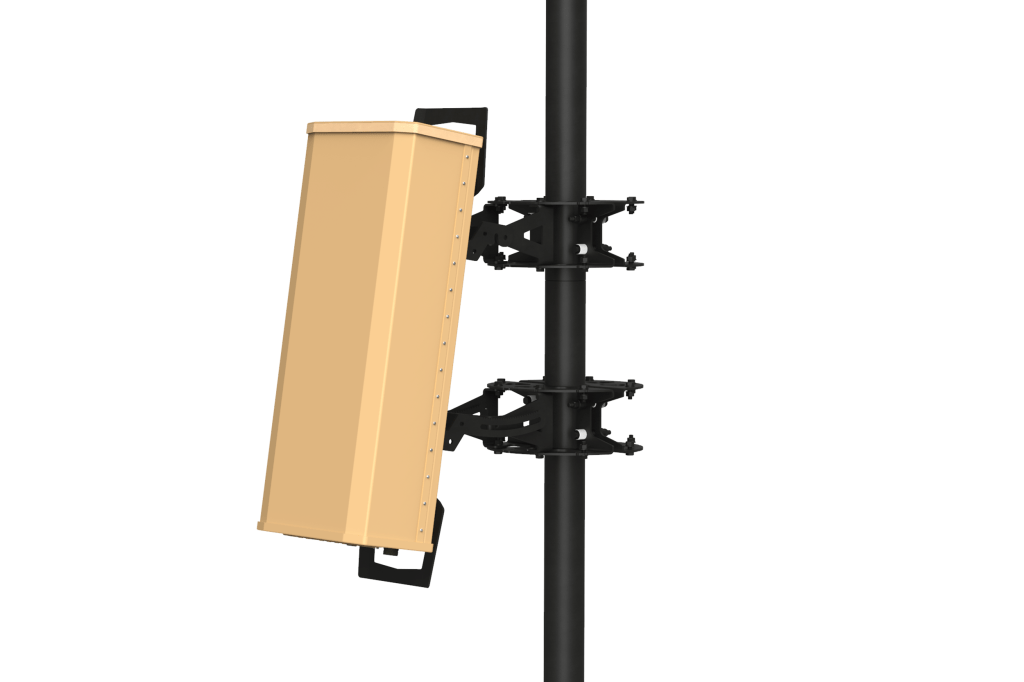

DroneCannon Mk2: Fixed-site device that works like the DroneSentry-X but with greater range.

ANALYSIS

Investment adviser MOTLEY FOOL’S analyst KATE LEE says DroneShield has remained a buy recommendation since 2021.

Lee says it was one of the few companies in the space on a global scale, and there were significant barriers for others to enter owing to the slow nature of government relationships. She points out that five years after its founding, the company’s annual sales to the US government remained under $500,000 before surging to $9.1 million in 2022. Prisons, airports and sports stadiums provide plenty of upside, she says.

The company’s total revenue was $17 million last year. Now, with the $33-million US government contract and an order backlog of $62 million, Vornik predicts revenue approximately four times last year’s, which he says will tip the company into profit for the first time.

“The North Star is $300 million to $500 million revenue in the next three to five years,” says Vornik. “There are three streams of revenue: sale of hardware, SAAS and our R&D projects for the Australian Government.”

Vornik recognises that scaling hardware is difficult, and so, once their hardware is widely distributed, he hopes that within five years, half the company’s revenue will come from software subscriptions – updating for new threats like anti-virus software.