Helsing built a $4.5 billion business on a pledge to transform Europe’s militaries with software, not hardware. Now its reversed course with plans for a fleet of attack drones.

By Iain Martin and David Jeans, Forbes Staff

When Helsing’s CEO and cofounder Torsten Reil took to the stage of a tech conference in a London church-turned-event space last September, his vision for the $4.5 billion defense startup was clear. “We are not a hardware company. We’re a software company. That’s all we do,” he said.

The pitch was radically different from other defense startup entrepreneurs like Anduril billionaire Palmer Luckey or Shield AI’s Ryan Tseng, who want to build their own missiles and drones, eventually challenging defense giants like Raytheon or Lockheed Martin. Instead, Reil said Helsing would focus on software alone, using AI to supercharge Europe’s militaries and arms makers. “It’s specifically about adding capabilities to existing assets,” Reil, a former video games developer, explained at another event in 2022.

Now, he’s made a 180 degree shift. Helsing this week unveiled the HX-2, a drone with a 50-mile range, capable of hunting in swarms and destroying armored vehicles. “When deployed along borders at scale, HX-2 can serve as a powerful counter invasion shield against enemy land forces,” Niklas Köhler, cofounder of Helsing said in a statement.

Peter Quentin, a Helsing spokesperson, said the company had recently started manufacturing the HX-2 drones in Germany, adding that they would be cheaper than comparable systems. Riel told Bloomberg earlier this week that the company planned to produce tens of thousands of the devices a year, adding the drone “has the capability to create a deterrence level that currently just isn’t feasible.”

Helsing’s pivot follows a string of deals the company signed with European arms manufacturers like Germany’s Leopard tank maker Rheinmetall and plane maker Airbus, and Swedish aerospace group Saab. Cofounders Reil, Köhler and Gundbert Scherf had pitched investors on its AI, which has been used to upgrade the radar system of Saab’s Griphen fighter jets, and to level up the German Luftwaffe’s Eurofighters.

The company had started designing and manufacturing its own drones after it couldn’t find an existing product that matched the specs it needed, said a Helsing investor, who requested anonymity to speak freely. “There’s no prime in that space and these drones are quite commoditized, but only with AI and autonomy they become game changing,” the investor said. “If you want to drive AI into the drone space you need some vertical control.”

Helsing’s Quentin disputed the company had struggled to find a partner. “We partner with industry across all domains, whenever it is possible to pursue approaches that are truly software-defined, but decline to simply sub-contract when that is not possible.”

Investors have plowed more than $100 billion into defense startups since 2019, according to Pitchbook, but only Anduril, which raised $1.5 billion at a $14 billion valuation this year, commands similar resources to Helsing. Helsing’s valuation soared to $4.5 billion in July after raising $480 million from American venture funds General Catalyst and Accel in a deal first reported by Forbes. That followed an earlier $325 million raised from investors including Spotify billionaire Daniel Ek’s investment firm since its launch in 2021.

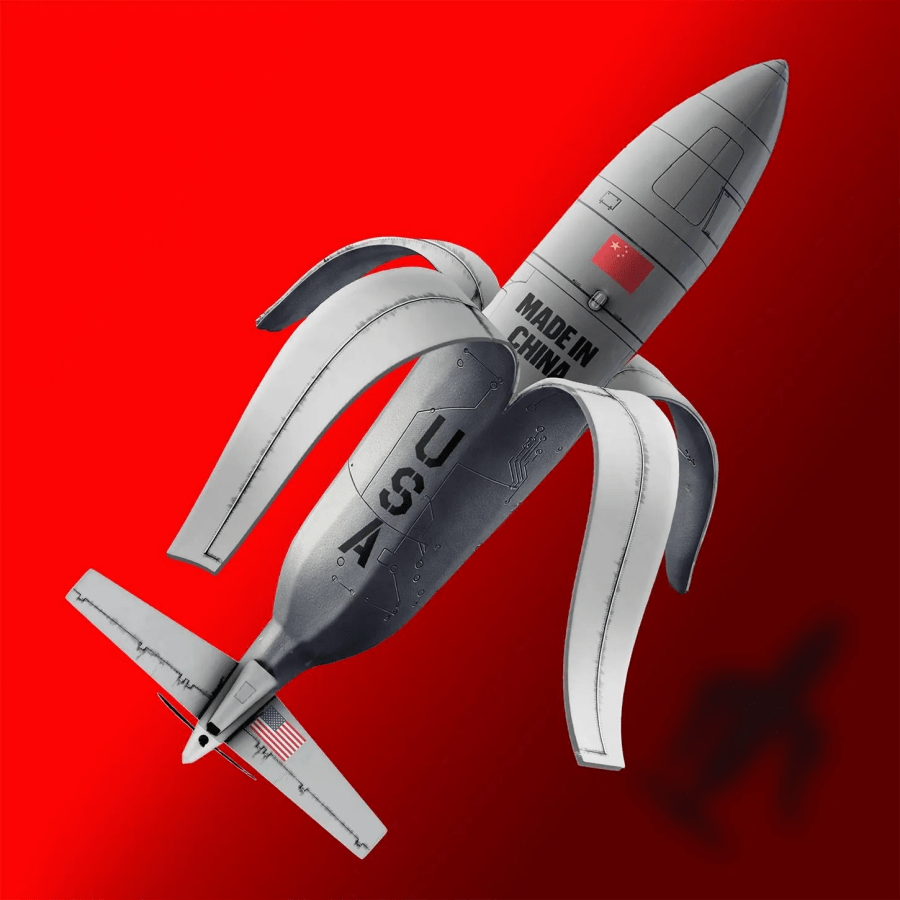

Europe’s most valuable defense startup now enters an incredibly competitive landscape. Aside from Chinese-made drones that have dominated the market, Helsing is also facing an uphill battle against American incumbents like Anduril, Shield AI and Skydio, which have been building small, expendable drones for years. It could also impinge on the territory of its own partners like Saab, Airbus and French missile maker MBDA, which all have their own drone programs.

Defense startups have encountered significant challenges in deploying drones in Ukraine, where the Ukrainian army has found success by instead churning out thousands of drones with off-the-shelf parts. Daily tinkering and updates near the frontline have helped them stay ahead of the invisible battle with Russia to jam the radio signals and GPS technology that allows drones to navigate and receive instructions from operators. The level of jamming is so intense both Russian and Ukrainian forces are now fielding drones tethered with fiber optic cables so pilots have hardwired controls.

American-made drones, meanwhile, have been less effective, with many of them crashing or glitching out. “The biggest challenge is electronic warfare with jamming and spoofing and that’s why U.S.-made drones are not performing that well in Ukraine,” says Kateryna Bondar, a fellow with the Wadhwani AI Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Still, companies like Shield AI and AeroVironment have landed deals to supply Ukraine’s Defense Department with drones; Germany’s Quantum Systems is also building its own UAVs in Kyiv.

“Companies that are trying to grasp what the Ukrainians are achieving, knowing where the sweet spot is going to be, they have to be engaged” on the ground, said Andrew Michta, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “And quite frankly, some of our technological solutions are not hitting the sweet spot.”

Helsing’s pivot has surprised some. Quantum Systems’ founder Florian Seibel, who’d unsuccessfully asked Reil to invest in his own military drone startup, said that his message remained consistent: building hardware was a race to the bottom on pricing. “He was all in on software,” Seibel recalled. (In a since-deleted Linkedin post, previously reported by Bloomberg, Seibel had criticized Helsing’s plans for its new drone, stating “The war in Ukraine is deadly and shouldn’t be misused for marketing purposes.”)

Other defense founders have warned that the nature of the procurement process for militaries has made software a hard sell. “To sell software without a hardware product is almost impossible,” one defense startup founder told Forbes. Shield AI’s cofounder Brandon Tseng testified to Congress in September that the U.S. Department of Defence often treated software as an afterthought in deals based around hardware.

Reil’s company will at least have a head start in Ukraine. It opened an office in Estonia last year and has reportedly had staff operating in Ukraine since at least 2023, according to Wired. It is possible drones could be tested in action as soon as this month. Germany’s Minister of Defense Boris Pistorius announced in November that 4,000 drones equipped with Helsing’s AI software would be donated to Ukraine starting in December.

These won’t be Helsing’s new HX-2 but instead will be a cheaper, wooden model dubbed HF-1 which will be made in Ukraine by local startup Terminal Autonomy, sources close to the deal told Forbes. Helsing says these drones have already been certified by the Ukrainian government and will use its AI and computer vision technology to navigate the battlefield without satellite assistance. The BBC reported earlier this year that Terminal Autonomy’s Bayonet drone cost a few thousands dollars to produce.

Helsing said it planned to use its recent funding, one of Europe’s largest rounds this year, for its research and development and to help “secure NATO’s eastern flank”. The company has previously revealed few details about its AI-powered software, hinting only that the tools give commanders a battlefield overview.

But Reil and his investors now seem to be betting that hardware is easier to crack than software. “We always talk about internally that the capability leap that we want to make is always at least 10X,” Reil said at the September 2023 event. “And for us, this is not a marketing claim.”