In a pristine environment, diesel spills can disrupt local ecology with long-lasting effects, but researchers from Australia are looking for better clean-up solutions.

Fuel spills are historically one of the key environmental risks of Antarctic stations and responding to a spill in such an extreme environment of isolation and sea ice can be extremely difficult. While improved fuel management has reduced the incidence of spills in recent years, research has shown that the impact of so called ‘legacy spills’ can still be seen for decades.

Kristopher Abdullah is a PhD student based in UNSW Sydney working on a project that’s being spearheaded by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) to utilise native bacteria in Antarctic soils to clean up diesel spills. In a Q&A with Forbes Australia, Abdullah talks about the importance of finding better, more efficient solutions to protect the area.

What is your research and what prompted you to undertake the project?

KA: My research is based around the soil remediation project that is currently taking place in Casey station in Antarctica. The overall goal of this project is to clean up several diesel spills by excavating the contaminated soil and constructing it into mounds called biopiles. The AAD is interested in how we can enhance the ability of naturally occurring microbes to break down hydrocarbons and safely reuse the soil in Antarctica. My research specifically is looking into the microbiology of the biopiles to determine what microorganisms are residing in them and what they are doing. We hope to find ways to increase the efficiency of the process as well as identify why some of the biopiles experienced toxic nitrite accumulation and how to prevent this in the future.

I’ve always had an interest in microbiology and the potential for microorganisms in biotech applications and the fact that the project is based in Antarctica made it even cooler.

What is the importance of what you are doing?

KA: The importance is twofold: the first is that there is a legal obligation for Australia to clean up spills that have occurred on its Antarctic bases as a signatory of the Antarctic treaty and secondly, I believe we have an ethical obligation to maintain Antarctica as one of the world’s most pristine locations.

Who are you working with?

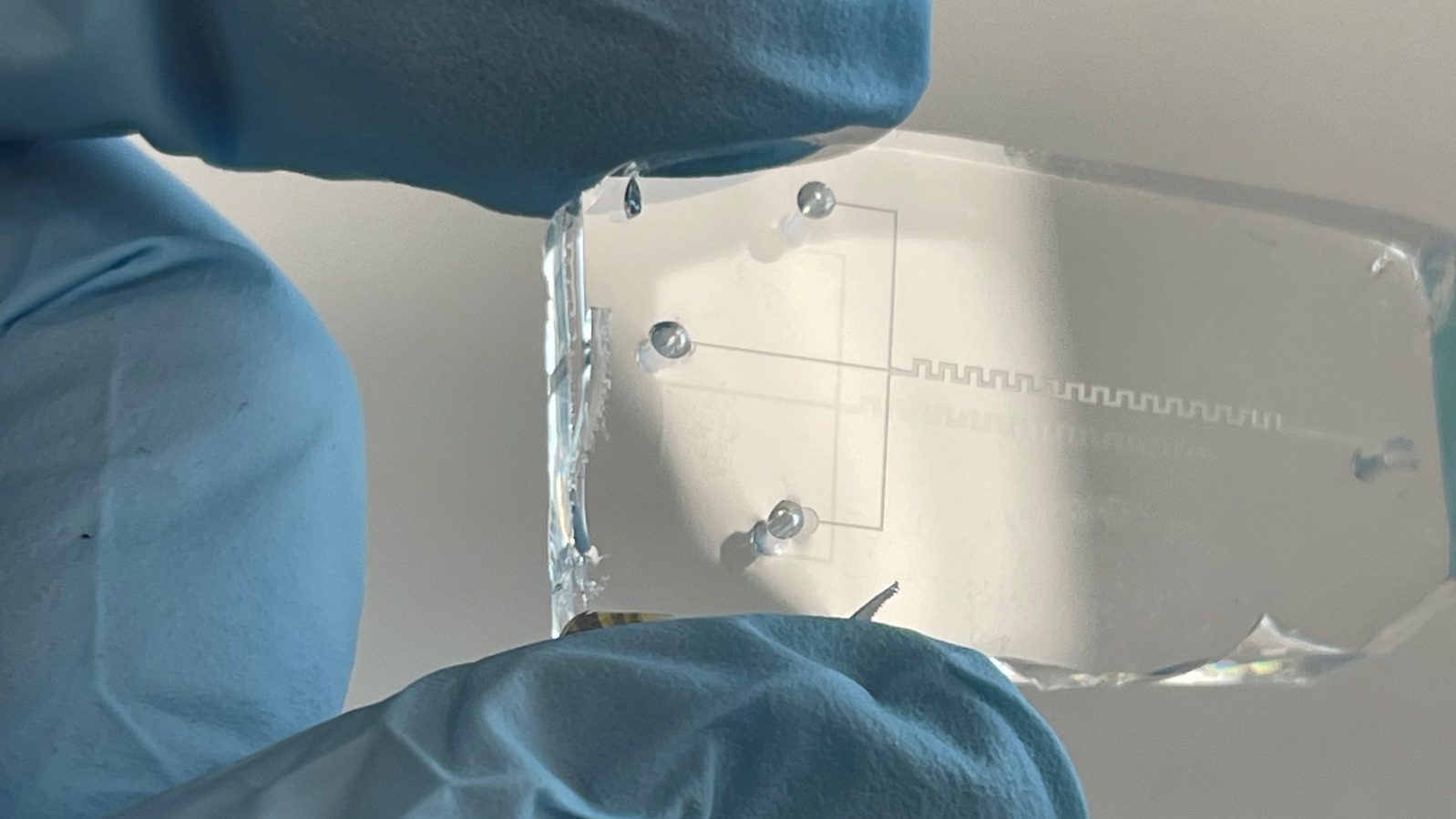

KA: I’m based in UNSW working within the Ferrari Lab, we collaborate with colleagues from the Environmental Stewardship Program at the Australian Antarctic Division, which is part of the federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

What are the impacts you can see; what is the potential?

KA: Probably the biggest impact would be putting a spotlight on the addition of nutrients to biopiles- previously the addition of nitrogen was calculated to optimise the removal of hydrocarbons only, but I think our research to date shows that there is more to the picture than that. Further down the line there is potential for molecular techniques to be used in eco-toxicology assays for example identifying a combination of genes that indicate the microbiome is experiencing stress from a particular toxic compound. In addition to Australia’s research station at Casey there are over 42 nations signatory to the Antarctic Treaty, and 110 bases in Antarctica, many of which have been abandoned,so there is a lot of potential to clean up Antarctica.

What of the benefits of collaboration?

KA: Without collaboration I wouldn’t be able to be part of this project at all. It also keeps us more closely connected to the real-world applications and objectives of our work which can often seem far away from the lab bench.

What is the importance of this undertaking in this environment and where else might it be applicable?

KA: Unlike in warmer climates or the ocean, hydrocarbon spills in terrestrial Antarctica persist for a long time and don’t really show any degradation when left alone. In other words, if we don’t clean this up nothing else will. While each site would be different in terms of contaminants and microbes present, this research will be applicable to other cold climate remediation programs, such as those in the Arctic, including in places like Greenland, Canada and Russia.

How have advances in this area changed our perspective on the issue and where will the focus be moving forward?

KA: I think generally our perspective has broadened to encompass not just the removal of hydrocarbons from soil but also being mindful of what other potential side-effects could result from bioremediation efforts. Moving forward I think advancements in molecular techniques will lead to more detailed inquiries into the metabolic activity of microorganisms in these biopiles. The beauty of researching microorganisms from Antarctica is that there is still so much left to discover and learn about life on the edges of our planet.