Armed with a newly raised $640 million, Groq thinks it can challenge one of the world’s most valuable companies with a purpose-built chip designed for AI from scratch.

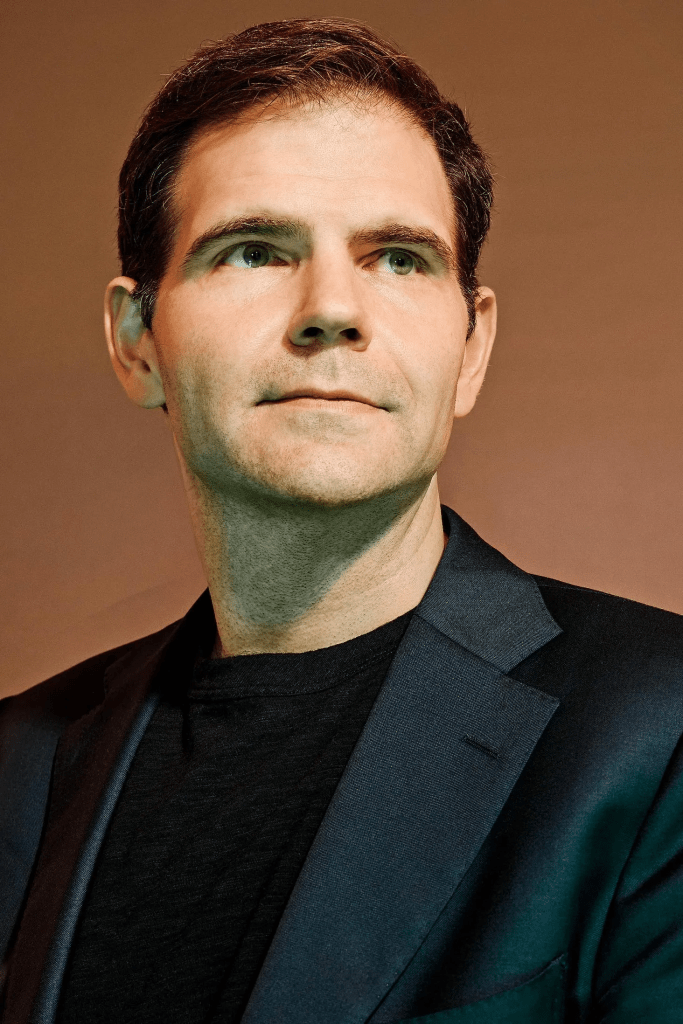

Jonathan Ross’s first inkling that something was wrong came back in February while he was speaking to a host of Norwegian Parliament members and tech execs in Oslo. Ross, the 42-year-old CEO of AI chip startup Groq, was in the middle of a demo he hoped would vitalise the languishing company: an AI chatbot that could answer questions almost instantaneously, faster than a human can read.

But, for some reason, it was lagging slightly. It unnerved Ross, who was pitching a Groq-powered European data centre that would showcase the specialised chips responsible for those super-fast answers. “I just kept checking the numbers,” he recalls. “People didn’t know why I was so distracted.”

The culprit was an influx of new users. A day before Ross’s Oslo meeting, a viral tweet from an enthusiastic developer raving about “a lightning-fast AI answer engine” sent tons of new traffic to the online demo, buckling the company’s servers. It was a problem, but a good one to have.

When he founded Groq eight years ago, Ross’s idea was to design AI chips explicitly for what’s known in the industry as “inference”: the part of artificial intelligence that mimics human reasoning by applying what it’s learned to new situations.

It’s what enables your smartphone to identify your dog as a Corgi in a photo it’s never seen before, or an image generator to imagine Pope Francis in a Balenciaga coat. It’s quite different than AI’s other computational suck: training the massive models to begin with.

But until OpenAI released ChatGPT in late 2022, touching off a global AI frenzy, the demand for superfast inference was limited, and the company was limping along.

“Groq nearly died many times,” Ross says from inside the startup’s semiconductor lab in San Jose, California, recalling one low point in 2019 where the startup was a month away from running out of money. “We started Groq maybe a little bit early.”

But now, with the demand for computational power to build and run AI models so intense that it’s contributing to a global electricity shortage, Groq’s time has seemingly come—either as a potential noisemaker or acquisition target for the legacy chip giants.

On Monday, the company exclusively told Forbes it raised a monster Series D round of $640 million, vaulting it to a $2.8 billion valuation, up from $1.1 billion in 2021. The round, led by BlackRock Private Equity Partners, also includes Cisco Investments and the Samsung Catalyst Fund, a venture arm of the electronics giant that focuses on infrastructure and AI.

“Groq nearly died many times.”

Jonathan Ross, CEO, Groq

The need for compute power is so insatiable that it has spiked Nvidia’s market cap to $3 trillion on 2023 revenue of $60.9 billion. Groq is still tiny by comparison, with 2023 sales as low as $3.4 million and a net loss of $88.3 million, according to financial documents viewed by Forbes.

But as interest spikes in its chips, the company has forecasted a perhaps optimistic $100 million in sales this year, sources say, though they were doubtful the company would be able to hit that target. Groq declined to comment on those figures.

With the AI chip market expected to hit $1.1 trillion by 2027, Ross sees an opportunity to snag a slice of Nvidia’s staggering 80% share by focusing on inference. That market should be worth about $39 billion this year, estimated to balloon to $60.7 billion in the next four years, according to research firm IDC. “Compute is the new oil,” Ross says.

Challengers like Groq are bullish because Nvidia’s chips weren’t even originally built for AI. When CEO Jensen Huang debuted its graphics processing units (GPUs) in 1999, they were designed to run graphic-intensive video games.

It was serendipitous that they’ve been the best-suited chips to train AI. But Groq and a new wave of next-gen chip startups, including Cerebras ($4 billion valuation) and SambaNova ($5.1 billion valuation), see an opening. “Nobody who started with a clean sheet of paper chose to make a GPU for this kind of work,” says Andrew Feldman, CEO of Cerebras.

It’s not just startups looking to dethrone Nvidia. Both Amazon and Microsoft are building their own AI chips. But Groq’s chips, called Language Processing Units (LPUs), are so speedy that the company thinks it has a fighting chance. In a pitch deck to investors.

The company touts them as four times faster, five times cheaper, and three times more energy efficient than Nvidia’s GPUs when they’re used for inference. Nvidia declined to comment on the claim.

“Their inference speeds are clearly demonstratively better than anything else on the market,” says Aemish Shah, cofounder of General Global Capital, which invested in multiple Groq funding rounds.

Groq started selling its chips two years ago, and has since added customers like Argonne National Labs, a federal research facility with origins in the Manhattan Project, which has used Groq chips to study nuclear fusion, the type of energy that powers the sun. Aramco Digital, the technology arm of the Saudi oil company, also inked a partnership to use Groq chips.

In March, Groq launched GroqCloud, where developers can rent access to its chips without buying them outright. To lure developers, Groq offered free access: in its first month, 70,000 signed up.

Now there are 350,000 and counting. On June 30, the company turned on payments, and it just hired Stuart Pann, a former Intel exec and now Groq COO, to quickly scale up revenue and operations. Pann is optimistic about growth: More than a quarter of GroqCloud customer tickets are requests to pay for more compute power.

“The Groq chip really goes for the jugular,” says Meta chief scientist Yann LeCun, Ross’s former computer science professor at NYU who recently joined Groq as a technical advisor. Late last month, CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that Groq would be one company providing chips to run inference for Meta’s new model Llama 3.1, calling the startup “innovators.”

“The Groq chip really goes for the jugular.”

Yann LeCun, Chief Scientist, Meta

Ross cut his teeth at Google, where he worked on the team that created the company’s “tensor processing units” semiconductors, which are optimized for machine learning. He left in 2016 to start Groq, along with fellow Google engineer Doug Wightman, who served as the company’s first CEO.

That year, Groq raised a $10 million round led by VC fund Social Capital. But from there, finding new investors was difficult. Groq cofounder Wightman left a few years later, and did not respond to interview requests.

There’s still plenty of naysayers. One venture capitalist who passed on the company’s Series D round characterized Groq’s approach as “novel,” but didn’t think its intellectual property was defensible in the long term.

Mitesh Agrawal, head of cloud for the $1.5 billion AI infrastructure startup Lambda, says his company doesn’t have any plans to offer Groq or any other specialised chips in its cloud. “It’s very hard to right now think beyond Nvidia,” he says. Others question the cost-efficiency of Groq’s chips at scale.

Ross knows it’s an uphill climb. “It’s sort of like we’re Rookie of the Year,” he says. “We’re nowhere near Nvidia yet. So all eyes are on us. And it’s like, what are you going to do next?”

Additional reporting by Rashi Shrivastava, Alex Konrad and Kenrick Cai.

This story was originally published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter hereor become a member here.