The Australian quantum start-up, Diraq, which hopes to build a quantum computer the size of a fridge utilising standard silicon chips, has announced it has achieved “record control accuracy of 99.9% for a quantum bit (qubit)”.

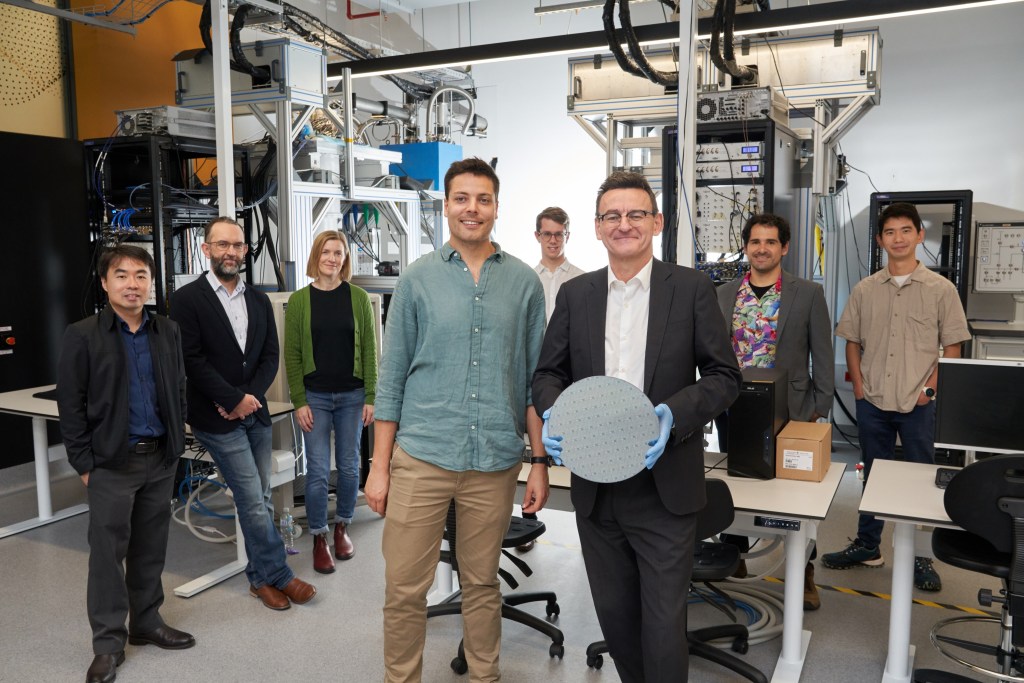

Diraq, spun out of the University of New South Wales in 2022 by Professor Andrew Dzurak, has already raised US$135 million from private and government sources.

To coincide with the new milestone, it has announced that it is partnering with US-based GlobalFoundries Inc to manufacture the chip – which has both quantum and classical processors – this year. It also revealed its partnership with Belgium-based IMEC – a world leader in chip design.

“By confirming 99.9% single qubit control fidelity, Diraq reaches the level of precision required for powerful, full-scale, error-corrected quantum,” the company said in a statement.

Diraq’s chip is designed to operate at -272.15 degrees, which is just one degree warmer than absolute zero, at which most other quantum computers are predicted to need to operate. That small difference is claimed to give it a real-world application advantage.

The type of chip used is the same as that used in mobile phones.

Diraq’s efforts have been overshadowed recently by the announcement of $940 million in federal funding to go to the US-based PsiQuantum and its Australian-origin team to build a quantum computer in Brisbane.

They also compete with the more high-profile Silicon Quantum Computing, which is headed by former Australian of the Year Michelle Simmons, and is also based at UNSW. Diraq spun its technology out of Simmons’ company in 2022.

“You might note that PsiQuantum also use GlobalFoundries for their photonic chips. But because their qubits are around a million times larger they need many, many chips (and cryogenic systems) to make one quantum computer, whereas we can get everything on one chip – and therefore in one compact unit,” Dzurak told Forbes Australia.

The recent performance demonstration was achieved using a qubit device manufactured by IMEC, “the world’s leading independent nanoelectronics R&D hub,” based in Leuven, Belgium, Dzurak said, making the relationship public for the first time. “This relationship is crucial for Diraq’s technology roadmap, through which we intend to achieve a fully error-corrected quantum computing system ahead of our competitors.”

“In over 30 papers in Nature-group journals over the past decade, the Diraq team has produced multiple world-first results for silicon spin qubit research and has patented their technology along the way,” the company said in a release.

In a Nature paper from March, Diraq’s team demonstrated the high-fidelity operation of silicon qubits at a temperature of one kelvin – high enough to cope with the heat generated by the classical transistors needed to control a quantum processor.

Of the company’s US$135 million investment, US$35 million has come from private sources, with more in the pipeline, Dzurak told Forbes Australia.

The company announced a second Series A fundraising in February led by French investment firm Quantonation which is a quantum specialist. “But that round also included funding from an Australian family fund, Higgins Family Investments. They’re a Melbourne-based family investment firm.” The Higgins family runs Higgins Coatings, a 70-year-old painting company.

“And UNSW also participated in that second Series A round,” Dzurak said. “That was on top of our initial round when we launched in 2022 with (Bermuda-based) Allectus Capital.”

Diraq has 35 staff in Sydney and is about to take on some in the US, Dzurak said.

“The big advantage of our technology, is that our quantum computers will be compact. I mean, they’ll be the size of a rack in a data centre, or maybe two racks in terms of physical size, and they’ll be consuming energy in the kilowatts, whereas our competitors are looking at systems requiring megawatts of energy in order to perform computations in physically enormous systems. You only have to go to their websites and look at what they’re proposing. These are large buildings, very large buildings, often multiple buildings in order to make one computer.

“But from our perspective, quantum computing is genuinely going to become a ubiquitous capability. If so, we have to make them affordable, and we have to make them compact.”