The Google cofounder has already donated more than $1.5 billion to Parkinson’s research. Now, as he takes on autism, he’s also investing in venture funds and startups working to develop therapies and treatments.

On March 26, 2024, Nicole Shanahan stepped onto the national stage as Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s vice-presidential running mate. On that day, and in many later public comments, Shanahan shared details of her young daughter’s autism diagnosis, tying it to a vaccination she received as an infant. There is no evidence that vaccines cause autism, but Shanahan—describing herself as an “autism mom”—broadcast that debunked theory throughout her five-month VP campaign. “My daughter has lifted the veil for me,” Shanahan said on a podcast a day after accepting the nomination. “If we’re talking about my support for Bobby Kennedy, that is what has brought me to this movement: financially, spiritually and perhaps other ways.”

Far from the campaign trail, her ex-husband and daughter’s father, Google cofounder Sergey Brin, has never spoken publicly about their child or Shanahan’s beliefs. Yet in early 2022, members of his philanthropy team began to explore ways to help. After more than two years of planning and nearly $50 million in funding for autism research to date, Brin is launching a new initiative called Aligning Research to Impact Autism (ARIA) that will fund research into what causes autism as well as therapies for it. The long-term budget for the project hasn’t been finalized, but will greatly exceed what’s been spent so far, according to a person familiar with Brin’s philanthropy strategy. Its first program, called the IMPACT Network, aims to link a group of autism care centers and affiliated researchers who will collaborate and coordinate on clinical trials; applications to join the network are set to open in the next few months.

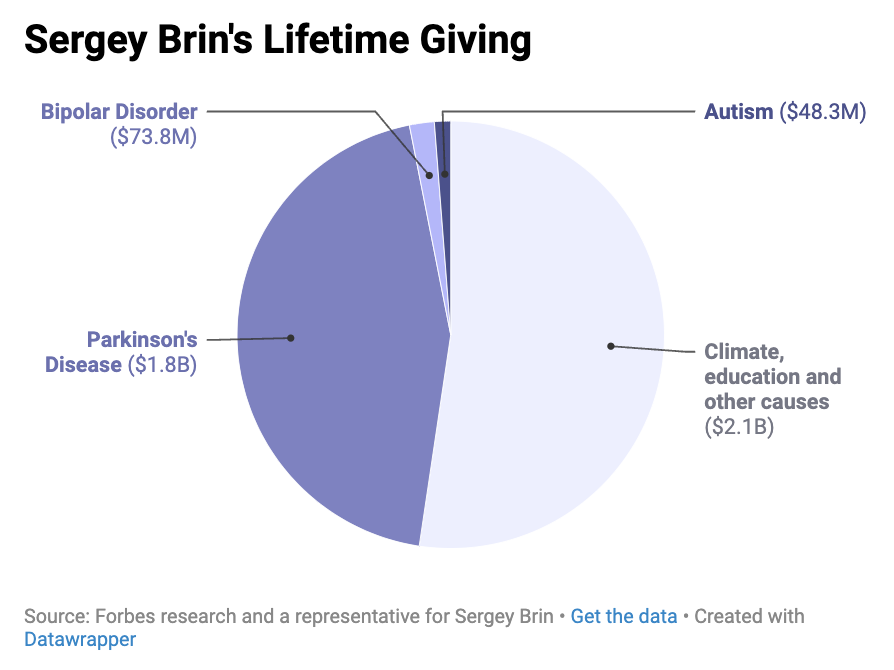

Brin’s focus on autism is his latest effort to direct the bulk of his substantive philanthropic giving to conditions that affect the central nervous system (CNS), all organized under an umbrella called the “CNS Quest,” according to Ekemini Riley, who has a PhD in molecular medicine and helps lead the CNS Quest initiatives. Much of Brin’s initial giving emphasized the basic science behind Parkinson’s disease, starting more than a decade ago, and bipolar disorder in 2022, as Forbes previously reported. While Brin hardly ever talks to the press and keeps his life private, all three conditions—Parkinson’s, bipolar and autism—have affected members of his family. His mother, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease more than two decades ago, died in December at age 76. In 2010, Brin also disclosed in a rare interview that he has a higher risk of getting Parkinson’s due to a genetic mutation that his mother also had.

“This work is personal because it starts with Parkinson’s disease, and I carry one of the genetic mutations discovered, the G2019S mutation to the LRRK2 gene,” Brin, the seventh richest person in the world, wrote in an email to Forbes. “This work led to the discovery of a new GBA1 gene variant that increases the risk of PD [Parkinson’s disease] in people of African ancestry. I’m optimistic about similar discoveries that will improve care for people with bipolar disorder and autism.”

Of Brin’s nearly $900 million in philanthropic grants last year—nearly double his 2023 giving and a quarter of his $3.9 billion in lifetime charitable giving—about half went to causes related to CNS Quest. Brin has also started backing startups and venture capital funds of late that are working on for-profit solutions and treatments, investing more than $600 million to date, including about $400 million in 2024 alone. While any profits will be reinvested or donated to nonprofits, it’s another way to push progress.

Brin has already spent $1.75 billion on research of Parkinson’s, a devastating degenerative disease that affects 10 million people globally, more than any other single person. He’s one of just a few people globally who’ve donated that much toward one disease. (Others include Bill Gates, Melinda French Gates and Warren Buffett toward polio eradication and the late real estate billionaire Harry Helmsley and his wife Leona toward Type 1 diabetes). The dedication and collaboration he applies to his philanthropy has already started to pay off. In November 2023, researchers funded by Brin’s Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) program and its partner, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, discovered the gene variant that Brin touted in his email to Forbes–one that nearly quadruples the risk of the disease among people of African ancestry. And last August the FDA issued a letter of support encouraging scientists and drug developers to use a spinal fluid test for early Parkinson’s diagnosis that was funded in part by ASAP.

Researchers funded by the Brin-backed Parkinson’s initiative ASAP traveled to Rome from more than a dozen countries last year to share ideas and talk about their research.

Miranda Perry

Brin has also been heavily funding efforts to study bipolar disorder, a serious mental health condition that affects some 40 million people worldwide. In 2022, Brin and two wealthy couples—all of whom have family members diagnosed with bipolar disorder—committed $50 million each over five years to an entity called Breakthrough Discoveries for Thriving with Bipolar Disorder, or BD2 for short. Brin has already donated $75 million to researching the disorder.

By early 2022, Brin’s team was already planning to focus on autism next. It soft-launched ARIA last October, focusing from the start not just on the basic science, where funding for autism has historically skewed, but also on potential therapies or treatments. “What we’ve learned and seen from our other initiatives is that it’s really important to fund both things in parallel, and have that feedback loop across both the science and the clinical side of things, like trial design, drug development and therapeutics,” says Riley, who co-leads ARIA. This is especially important in autism, since it is simply a neurological difference, not a disease to be cured.

Over the next five years, she adds, ARIA has big goals, including developing quantitative assessments for language, social communication or sensory dysfunction to help improve treatment for autistic people who seek it.

“I would like to ensure that everyone who has a complex neurodevelopmental condition like autism has an opportunity as an adult to live a life that allows them to fulfill their potential and live in an environment in which they feel safe, respected and appreciated for who they are,” says Katarzyna Chawarska, a psychiatry professor at Yale School of Medicine who researches early markers of autism and spoke to Forbes about Brin’s efforts.

To get to Brin’s goal of better treatments, his team has begun backing biopharma companies. In late 2021, Brin seeded Catalyst4—a type of nonprofit called a 501(c)(4) that can lobby as well as own entire for-profit companies—with more than $450 million worth of donated Alphabet and Tesla stock. (He invested in the electric vehicle company in 2008.) In 2023, he gave another $615 million to Catalyst4.

Catalyst4’s portfolio includes a majority stake in biopharma firm MapLight, which is developing treatments for brain diseases and autism. It currently has a drug candidate in Phase 2 clinical trials that aims to help with “social communication deficits” in certain autistic people. Catalyst4 also invested in Stellaromics, which makes detailed three-dimensional maps of gene activity in slices of tissue for other companies to use in drug development; early stage gene therapy company Capsida Biotherapeutics; and Octave Bioscience, which works on improved care for neurodegenerative conditions, starting with multiple sclerosis. One approach Catalyst4 has taken with several of its portfolio companies is to give “philanthropic” dollars (often some 25% of the total investment) along with making an equity investment, according to a person familiar with Brin’s philanthropy.

Catalyst4 also holds indirect stakes in additional startups through several investment funds. The largest is a dedicated fund at venture firm The Column Group, seeded in partnership with the Simons Foundation (founded by the late hedge fund billionaire Jim Simons and his wife Marilyn), that now has some $200 million in assets. The fund targets early-stage investments in drug discovery, vaccines, and gene and cell therapy startups aiming to develop treatments for neurological conditions.

The fund was created with Brin’s high tolerance for risk in mind, which sets him apart from other philanthropists and venture capital investors, according to renowned biochemist Robert Tjian, a professor at UC Berkeley who’s also an advisor at The Column Group and helped seed the idea for the fund. “It’s so difficult to work within the human brain, because you don’t have access to it, right? You don’t want to cut into it,” Tjian says. “That means the timeline of an initial investment in a problem to the time that it actually starts to pay off in a clinical study is probably longer than most VCs are willing to deal with.”

For goals as ambitious as Brin’s, “one other thing that should be obvious,” Tjian says. “You’re going to have to be lucky.”