If Curtis Priem, Nvidia’s first CTO, had held onto all his stock, he’d be the 16th richest person in America. Instead, he sold out years ago and gave most of his fortune to his alma mater Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Curtis Priem wanders across a wooden stage before coming to a standstill a few feet right of center. It’s one of the “acoustic sweet spots” in the 1,165-seat Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute concert hall that the Nvidia cofounder donated $40 million to construct between 2003 and 2008.

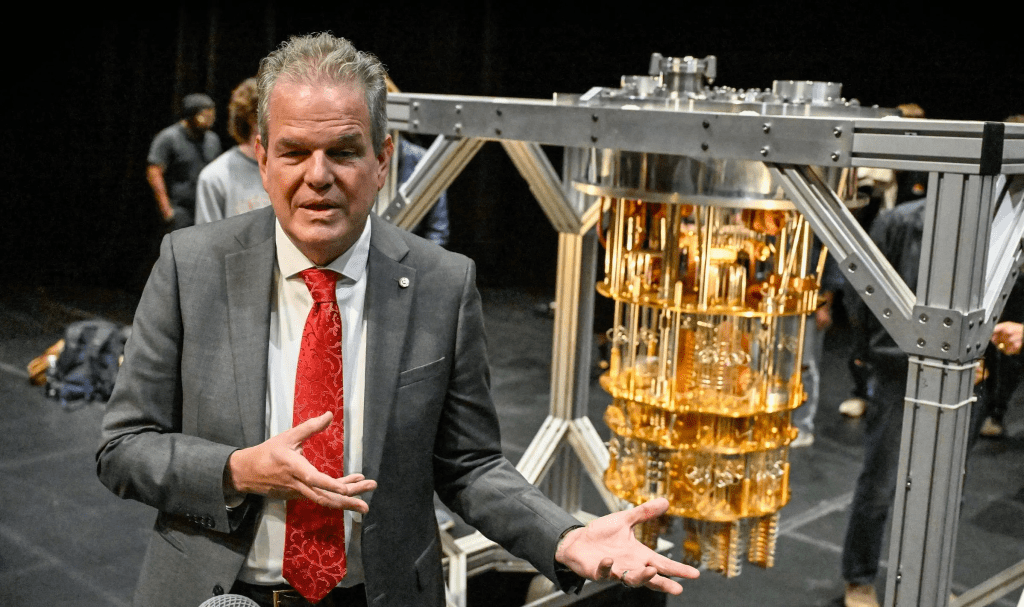

Bathed in warm stage lights, Priem, 64 and dressed in suit and red tie, gestures toward the thousands of uniquely curved wood panels lining the walls and tightly-woven fabric specifically tuned for air permeability and mass on the ceiling—all built for ideal acoustics.

“This is the most technically advanced performance space in the world,” the electrical engineer beams, describing the Troy, NY, venue that is named after him: the Curtis Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center.

It’s part of a much bigger commitment to his alma mater that most recently includes helping it become the first university in the world to house an IBM Quantum System One computer.

Expected to be operational by next spring, it will be the cornerstone of a new computational center that will hopefully help RPI and the surrounding area attract top talent.

Since 2001, Priem has given $275 million to RPI, accounting for 40% of RPI’s total gifts during that period, and he’s pledged approximately $80 million more. Only half that amount has ever been publicly acknowledged as gifts from Priem.

An anonymous pledge of $360 million was announced by RPI in 2001 around the time Priem started giving, but neither he nor the school would comment on whether he is the donor.

What’s even less known is Priem’s own story. An inventor who has almost 200 patents, he helped design the first graphics processor ever for PCs in the early 1980s and later cofounded semiconductor firm Nvidia, where he spent a decade working as its first chief technology officer.

Following Nvidia’s 1999 IPO, he transferred most of his shares to a charitable foundation, after deciding it was an “excessive amount of money” to hold onto.

A few years later he left the company, in part due to a highly litigious first marriage that ended in divorce and domestic violence allegations against his ex-wife. By 2006 he’d sold off his remaining shares.

Had he held onto his entire stake, he’d be worth $70 billion. Instead, Forbes estimates that Priem has a fortune that’s closer to $30 million, just over one-tenth of what he’s given to RPI.

That includes a $6 million home near Fremont, California where he lives off the grid with unreliable cell service and writes “manifestos” filled with equations about how to solve world problems like “repairing the earth.” (None have been published anywhere).

He says he often communicates by giving out unique email addresses—sixteen-digit strings of numbers including one given to this Forbes reporter, as a way of avoiding spam (he says he hasn’t gotten any since 2000).

He also owns a Gulfstream G450 private jet, named Snoopy, that he bought in 2021 and now uses to fly to RPI four times a year.

In an interview on RPI’s campus in the historically blue-collar town of Troy, NY, Priem opens up about his donations, why he left Nvidia and a few regrets.

“I did a little crazy thing, and I wish I’d kept a little bit more [Nvidia shares],” admits Priem, who says he still thinks of Nvidia twice a day—when he puts on and takes off his Omega Speedmaster X-33 Mars watch, the same model worn by Thunderbirds and Space Shuttle astronauts; it was a gift from Nvidia on his fifth company anniversary.

For him, RPI has become the place not only to put his money but also to find meaning and solace.

“Hell was happening for me on the outside, and [RPI] was actually my retreat,” says Priem of his work with RPI, where he has served on the board of trustees since 2003. “It became my purpose and my sanity.”

Priem chose RPI over the better-known Massachusetts Institute of Technology thanks in part to it having a fancy IBM computer he wanted to use. It turned out to be an ideal place for Priem, who had always been interested in the intersection of technology and the arts.

In high school, after moving “all over the east coast” as a child, his family settled outside Cleveland, where Priem took cello lessons with the Cleveland Orchestra’s Donald White, the first Black musician to play in a major orchestra, and spent two summers at an intensive camp for classical musicians in North Carolina.

He also played the trombone. At RPI, he played cello in its orchestra all four years, and credits much of his creativity in the electronics industry and his work at RPI to his musician upbringing.

“To perform, you have to practice, right? And you have to be creative,” Priem says. “So I started applying that to electronics and computer science.”

He graduated from RPI with a degree in electrical and computer engineering in 1982, and went to work as a staff engineer for PC company Vermont Microsystems, followed by a stint as a hardware engineer at electronic test equipment firm GenRad.

He later moved to California to work at Sun Microsystems for seven years.

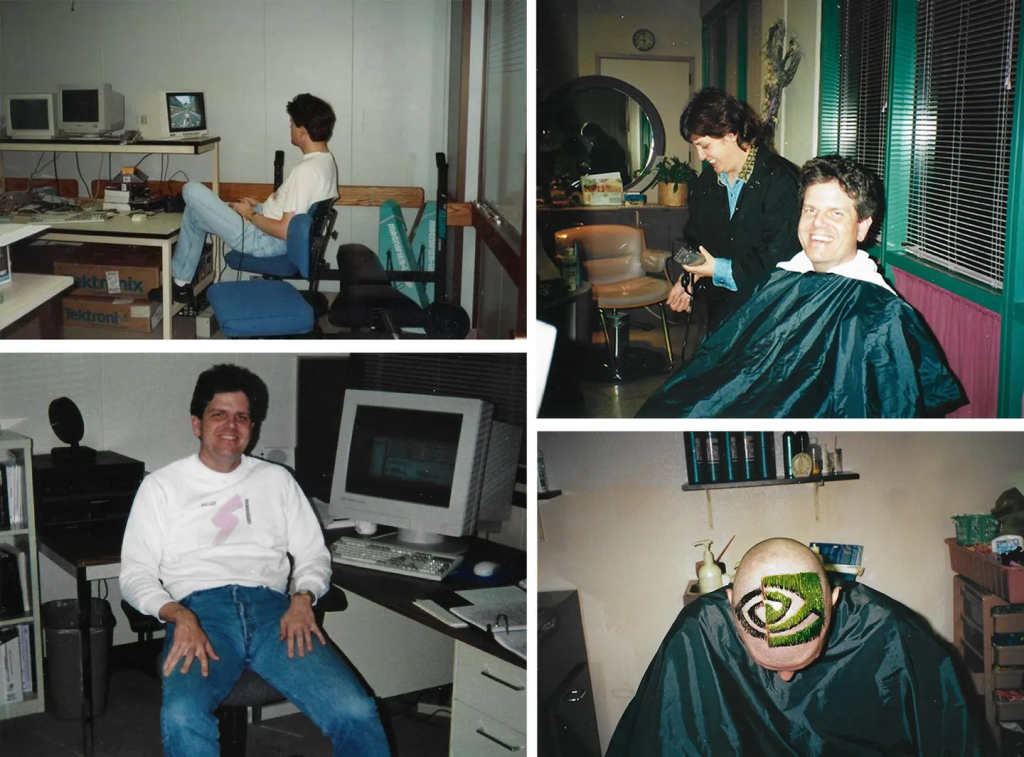

The idea for Nvidia was hatched in 1993 at a Denny’s in Silicon Valley. That’s where he, his Sun Microsystems colleague Chris Malachowsky and their friend Jensen Huang, an engineer who worked at LSI Logic, would meet up to brainstorm how to build a better chip.

Priem describes his role early on as the architect creating the underlying blueprint that allowed engineers to design algorithms for Nvidia’s chips, working mostly behind the scenes.

“There was a saying at Nvidia to never put Curtis in front of a camera, and never put Curtis in front of a customer,” Priem quips. (CEO Huang’s response: “Curtis was actually excellent with customers.”)

In 1999, Nvidia had two major breakthroughs: It went public with a $1.1 billion market capitalization and it invented its graphics processing unit, or GPU, which was initially used for video editing and gaming but eventually reshaped the computing industry.

That July Priem also married his first wife, Veronica, and two months later, established the Priem Family Foundation in which he put more than three-quarters of his 12.8% (at IPO) Nvidia stake–about 100 million shares (in today’s share count).

Part of the reason for the big gift, he said, was that he didn’t want the government to get the money if he had sold a bunch of shares and owed taxes on them.

It was also around that time that Priem looked at his shareholding and thought he’d end up with around $50 million. “My saving grace was that I couldn’t predict the future,” he says somewhat wistfully about his decision to sell off shares in the now $1.2 trillion (market cap) company.

After initially donating to a handful of causes including The Nature Conservancy and the Monterey Bay Aquarium, Priem shifted away from his goal of alleviating human-induced suffering to preventing it, mostly through education-focused giving.

“Adam and Eve had free will and chose a sinful path which originated suffering … our belief is that most suffering can be avoided since it is within our control to begin with,” stated his foundation’s early website, drawing on his family’s roots in the United Church of Christ (Priem doesn’t practice the religion, but his father, sister and grandparents were all ministers, he says).

In 2000, Priem went back to RPI to receive the university’s Entrepreneur of the Year Award for his work at Nvidia. “I walked onto campus, and it’s like, okay, this is sort of my calling,” Priem says.

He says he donated $1 million to RPI in 2000 and again in 2001. Then in the fiscal year ending in June 2002, the Priem Family Foundation began disbursing at least $10 million a year to RPI—and has done so ever since.

More than 40% Of Gifts to RPI Since June 2001 Have Come From The Priem Foundation

Things at Nvidia, meanwhile, weren’t going as well. According to Priem, he was distracted by personal issues at home and not contributing at the level he wanted, so he left.

The next decade of Priem’s life was a mess, he says—a court found that Veronica had a “history of domestic violence” against him.

He alleged in 2013 court filings that the violence had “generated 19 written police reports, five arrests, three criminal convictions, three criminal protective orders, one civil temporary restraining order, and three probationary periods.”

According to the same document, Veronica claimed that Curtis “triggered her violent reactions by provoking her verbally” and mentioned a “lack of severity associated with her misconduct.” (Her lawyer did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

At one point, Curtis Priem says he met with California state senator Bob Wieckowski to advocate for an amendment that would make it harder for alleged perpetrators of domestic violence to receive spousal support. The amendment, SB 28, passed unanimously in a 2015 Senate vote.

His ex-wife pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge of domestic violence, and he never paid spousal support.

Throughout this time, Priem continued to help RPI, which he said had financially “floundered” for decades. He wanted to help “turn this super tanker around.”

First, his donations went to the essentials—hiring more faculty, building renovations and acquiring lab equipment.

Then came contributions to what’s now the Shirley Ann Jackson Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies and to the performing arts center, which opened in 2008.

The idea for his biggest contribution yet came just months ago at a board retreat in Carlsbad, California.

That’s where Priem suggested to RPI’s new president Martin Schmidt that they try to bring a quantum computer to RPI, an interesting idea but one Schmidt thought would be too costly.

“We left Carlsbad with me agreeing that I would drive down to see Dario Gil, the head of IBM research … to see if we could convince him that IBM should put a quantum computer on the RPI campus,” Schmidt told Forbes.

Just three months later, in June, RPI formally announced plans to bring an IBM Quantum System One computer to campus next year, which will make it the only university in the world to house one.

“Now, with quantum computers, RPI will be at the forefront of ushering in a completely new paradigm of computing that offers profound possibilities for the exploration of a range of previously intractable problems across areas such as material design, sustainability, pharmaceutical development, healthcare and much more,” Gil said at an October groundbreaking event for the quantum computer.

Priem’s latest $95 million pledge to bring the computer to campus and set up a new center for it is, in his words, setting his foundation on the “glide path to zero.”

“This weekend is actually the termination of our foundation,” Priem said at the groundbreaking event, where he explained to a packed crowd of students, faculty, alumni and other guests that his funding for the computer would be his foundation’s last major gift and use up most of its remaining funds.

He made the announcement standing in front of a gleaming “quantum chandelier,” the heart of the forthcoming quantum computer because it contains the quantum chip and is surrounded by intricate gold wiring to keep the 2,000-pound computer cold enough to operate, at around -460 degrees Fahrenheit.

The computer is expected to be operational sometime in spring 2024 and will sit under four stained-glass windows in a former chapel.

Priem’s family foundation currently has $160 million in assets and is on track to wind down by 2031, he says, but he isn’t sure the money will last that long, given all the new initiatives he keeps deciding to fund at RPI.

“We can’t stop spending, so it’ll probably be a lot sooner than that,” says Priem, who adds that “when the money runs out, I get to retire.”

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.