As social media’s poster boy approaches 40, he’s having his Bill Gates moment: mellowing (a bit), maturing (a bit more) and upending his company with staggering confidence. It’s a big bet on the future of daily human life—and his legacy.

Sitting in a glass-walled conference room nicknamed The Aquarium, Mark Zuckerberg runs a cost/benefit analysis on the topic that has brought him headlines this year: mixed martial arts. Today, he’s focusing on head shots versus body shots. “Getting hit in the face doesn’t hurt that much,” he deadpans. “It just does brain damage.”

The obviously-never-going-to-happen cage match with Elon Musk (“I assumed he wouldn’t do it”) put Zuckerberg back into the zeitgeist in the stupidest way, but it also served a business purpose: For much of his career, he has undermined his monumental achievements by wading through a swamp of missteps and democracy-crippling scandals. So the Musk beef was rare: an opportunity to play hero to the Tesla CEO’s petulant villain, to demonstrate that Facebook’s former “toddler CEO” has evolved into Meta’s statesman.

“The thing that determines your destiny isn’t a competitor,” he says. “It’s how you execute.”

Photo by Guerin Blask for Forbes

Such reflection is well-timed. Zuckerberg will turn 40 next May, with a fortune estimated at $106 billion, a philanthropy arm designed for maximum impact and a commitment to transform one of the most important companies in the world, over which he has near total control. In many ways, he’s having his Bill Gates moment. Like Zuckerberg, Gates dropped out of Harvard to build a historically significant tech company. Like Zuckerberg, he was the nerdy boy-wonder face of his field. Like Zuckerberg, he produced fans, enemies and antitrust concerns on his brusque, relentless way to the top.

And then, in his 40s, Gates flipped the script. He transformed his image from unrepentant monopolist to global benefactor, with his company and legacy both winning because of it.

So what might that look like for Zuckerberg? His friend and peer, Spotify founder Daniel Ek, describes a narrative arc that brings us to the current moment.

There’s “The Social Network Mark,” Ek says, a nod to the 2010 movie that portrayed the Facebook founder as an arrogant, duplicitous genius. Then there’s “Cambridge Analytica or ‘evil Mark,’ ” he says, referring to the company’s data harvesting scandal.

Which brings us to the Mark of today. “He is a lot more authentic in his public persona,” says Ek, who emphasizes that his three Marks reflect public perception, not his own opinion. “He’s learned a lot over these past few years and he has a new fire in the belly. He’s realized he needs to act responsibly because he’s got this enormous platform. . . . But there’s still some of the old Mark, where he is betting on things even though everyone tells him ‘this is never gonna work.’ ” Most notably, what’s likely to be a $100 billion investment in a fantastical yet still unproven virtual world called the metaverse that may not pay off for another seven years, if ever.

MISSION IMPOSSIBLE | With his wife, pediatrician Priscilla Chan, Zuckerberg has shouldered a potentially Sisyphean goal: to help science cure, manage or prevent all disease by the end of the century. Says Chan: “We talked about things that we couldn’t imagine being true in our kids’ lifetimes.”

Meta

Zuckerberg has embraced a “martial arts view of the world,” personally and for Meta, he says. That speaks to respect, purpose, discipline and many other management textbook clichés. But ultimately, this third, more mature Zuckerberg will lean on another MMA principle: self-awareness. “When you go into a competition, you’re not fighting another person, you’re fighting yourself, right?” he says. “You’re just trying to be a better version of yourself.”

Zuckerberg has extraordinary leeway as he pursues this re-invention. Professionally, no one can tell him what to do. Facebook has a dual share structure which gives him unassailable control. Currently, he owns 99% of the super-voting Class B shares and has 61% of the overall voting power, making him both unfireable—and largely unaccountable.

“Can you gather all the other common shareholders to vote against Mark?” asks his friend and Facebook cofounder Dustin Moskovitz. “No, you can’t.”

This was Social Network Mark’s foundational move—suggested by Napster cofounder and former Facebook president Sean Parker, no less, and epitomized by Zuckerberg’s early business cards, which read I’M CEO, BITCH. In Facebook’s primordial days, the need for control of one’s own destiny was reinforced. Zuckerberg recalls the time in 2006 when Yahoo offered $1 billion to buy Facebook, then just two years old. “When I didn’t want to sell the company, I think the investors were thinking, ‘Maybe we should get a different team?’ And it’s like, ‘Oh, well, you can’t,’ ” he says, laughing quietly.

Zuckerberg understandably sees this as a feature, not a bug. “There are plenty of companies in the world that have a lot of capital . . . that don’t have the leadership or board structure that enables them to take big bets on the future,” he says. “We’re a founder-controlled company.”

That has no doubt helped Facebook make several acquisitions once seen as audacious but now viewed with respect (WhatsApp), curiosity (Oculus) or awe (Instagram, one of the best corporate purchases this century).

Yet these successes, as Facebook went public at a market capitalization of nearly $82 billion in 2012, also led to the Evil Mark period, which can be summed up in one word: hubris. In the mid-2010s, Zuckerberg barnstormed through the Midwest on a listening tour with fishermen, farmers and firemen. Meanwhile, back in Menlo Park, California, his company, which connects the world better than any other, was being used to assault democracy at a scale bigger than any other.

It’s serious stuff: In 2014, Facebook’s algorithm amplified calls for ethnic violence in Myanmar that helped incite genocide against the Rohingya minority. In 2016, Cambridge Analytica, consultant to Donald Trump’s campaign, improperly used data collected from Facebook with the intent to build voter profiles ahead of the presidential election. That same year, Russia in essence turned Facebook into a discord-inducing anti-democracy tool. In 2021, whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed that Facebook’s leadership had known about the harm its products could cause—and prioritized profit and growth regardless.

“Mark Zuckerberg’s legacy will be the key role his company played in undermining democracy,” says venture capitalist Roger McNamee, an early Facebook investor (and former Forbes investor) who has become an outspoken critic. “Without Facebook, the whole world would look completely different . . . and much better. For someone who had so much opportunity for good, this is a tragedy.”

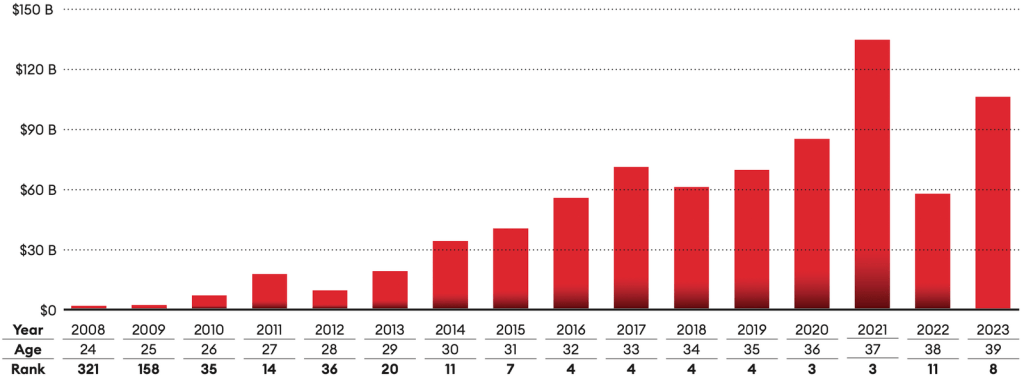

Zuckerberg’s Fabulous Fortune

In 2008, AT 24, the Facebook founder was the youngest self-made billionaire ever to join The Forbes 400. Seven years later, he was the youngest to crack the top ten.

To this, Zuckerberg—who originally dismissed concerns about 2016 election interference on Facebook as a “crazy idea,” even as it was going on under his nose—says, “Certain governments around the world will keep on trying to run different campaigns like this,” adding “I think our teams have gotten a lot more sophisticated about dealing with this.”

That’s about all we’ll likely get. Voting control largely shields him from consequences other than apologies. “We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake,” he told a congressional hearing in 2018, apologizing for the Cambridge Analytica scandal. “It was my mistake, and I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it and I’m responsible for what happens here.”

But responsibility and accountability are different. Especially when the giant asset firms that support him, including Vanguard, BlackRock and Fidelity, see that despite the stumbles, he has delivered an inarguably great track record for shareholders. Over the last three years, Meta’s shares have lagged the S&P 500 by nearly 16 percentage points, but they outperformed the index by 31 and 367 percentage points over five and ten years, respectively.

Benevolent dictatorships can, in theory, produce greatness. “There just aren’t that many places in the world where you can make the kind of long-term bets that we have,” Zuckerberg says, correctly. But without self-awareness, that benevolence looks more like the “evil” Mark to whom Ek referred—especially if the CEO’s reign could exceed a half-century.

“I think I’m going to be running Meta for a long time,” Zuckerberg says.

It’s hard to pinpoint anyone’s maturation, but in looking at Zuckerberg, and the third Mark, you could do worse than to consider September 2021.

Facebook stock had hit its all-time high. The company was now worth nearly $1.1 trillion, and Zuckerberg himself was worth some $136 billion. His push into the metaverse was moving apace. The following month he announced the decision to change Facebook’s name to Meta Platforms, staking its brand on a bet that the metaverse would become the future of computing—the very definition of a founder-driven big bet.

Then came the reckoning. Over the next 14 months, Meta’s shares plunged 75% as annual revenue fell for the first time, with 2022 net income sagging 41%. Zuckerberg’s fortune crashed to $33 billion. Apple’s 2021 privacy update to its mobile operating system, iOS, which made it harder for tech companies to track users across apps, played a role. Another culprit: competition from TikTok.

EYES WIDE SHUT | The latest version of Meta’s Quest headset offers “mixed-reality” (a blend of virtual reality and the physical world) and is due to be released this fall; it will cost $500. Pictured above: a prototype of the device.

Meta

Last year, then, Zuckerberg did something different. No plowing forward. No belated halfhearted apologies. Instead, he shifted. After taking his workforce from 33,600 to 87,000 in four years, Zuckerberg last November announced layoffs of more than 11,000 employees—13% of the company—then added another 10,000 to that number this March. “We made some really tough calls last year,” he says flatly. “It’s obviously not what you want to do.”

“We tried to set up the operating framework for the company for two goals,” he continues. “One was to set us up to operate more efficiently and build better products faster. The other was to make sure that we have the financial space to buffer whatever bumps we hit along the way so we can continue to invest in the long-term vision, which for the most part is these two major investments that we’re making in AI and the metaverse.”

The vision didn’t change, even if the metaverse has already been written off by some as a failure and Zuckerberg has said publicly it will take a decade before it makes money. Meta has already accumulated some $40 billion in opera-ting losses from its bet on the idea of an alternate virtual universe led by its Reality Labs arm, but Zuckerberg remains all-in. It’s tough sledding: Horizon Worlds—a free virtual reality app for its Quest VR headsets that was supposed to herald an era of immersive experiences and VR conference calls—reportedly failed to meet its 2022 target of 500,000 monthly active users, hitting fewer than 200,000, according to an internal document cited by the Wall Street Journal in February. Even Zuckerberg concedes Horizon Worlds isn’t as retentive as it needs to be. “It’s one thing to say, ‘Okay, this is an impressive experience,’ ” he says. “It’s another to say, ‘I want to do another meeting like that every week.’ ”

“I would probably make a different investment in Reality Labs, for example, if I were calling all the shots,” adds Susan Li, Meta’s chief financial officer.

Li notes that her remark won’t come as a surprise to Zuckerberg, who encourages such debate. And as he took in the criticism and course-corrected, markets responded. Meta’s stock has more than tripled in value since its trough in late 2022—helped along by about $38 billion worth of share repurchases since the start of last year.

Analyst consensus projects a 14% rise in revenue this year to nearly $133 billion and a whopping 50% jump in net income to $34 billion, bringing it much closer to its high two years ago. The resulting share upswing again made Zuckerberg one of the ten wealthiest people on the planet.

“What are you spending all this money on? ‘Well, we’re trying to fit a supercomputer into a pair of normal glasses.’ ”

For him, the metaverse is part of a long-term vision that encompasses not just VR and AR, but artificial intelligence as well. Like Gates, who in a February interview with Forbes described recent advances in AI as “every bit as important as the PC or the internet,” Zuckerberg sees the mainstreaming of AI as a transformative event. And, like many other tech giants, Meta has also built a large language model on which to train the AI that will define its future. Called Llama 2, it’s open-source and will be integrated into a variety of Meta’s products.

“AI will go across everything,” he says, outlining a now familiar new world that begins with intelligent assistants and ends with holograms of our colleagues in business meetings. Zuckerberg also sees AI powering a new suite of products that reportedly include chatbot “characters.”

He acknowledges AI is another one of those costly forward-looking gambles. But he’s the only Meta shareholder who matters, and he has plenty of patience. “Look, it’s going to take some more time to get to full augmented reality glasses. And that’s what a large percentage of the Reality Labs budget is going toward. So when people say, ‘What are you spending all this money on?’ It’s like, ‘Well, we’re trying to fit a supercomputer into a pair of normal glasses.’ ”

Should Meta manage to pull that off first in a compelling way, it could define a new market. If it doesn’t, it will be a costly fast failure like many before it: the Facebook phone, the now-abandoned Portals videochatting device, the botched cryptocurrency effort Libra.

“Our lived experience here is failures, constant failures, constantly doing things that we think people will love,” says Meta chief technology officer Andrew “Boz” Bosworth. “And they don’t love them and leave us asking, ‘Why don’t you love this?’ We ask that question rigorously. And then we iterate and iterate and iterate until we find the product market fit. That’s something we’re very good at.”

If the first two Marks are based on public perception, then the third Mark has surely realized how Gates transformed his image through the great public works he began to focus on in his 40s. Zuckerberg, just 26 at the time, was one of the original signatories of the Giving Pledge, the campaign spearheaded by Gates and Warren Buffett that asks billionaires to commit to spending at least half of their fortune on philanthropy.

“Bill believes very strongly that if you want to do philanthropic work well as a discipline, if you want to be good at it by the time you’re older, you need to practice,” Zuckerberg says.

In 2015, just before the birth of their daughter, Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, wrote her a letter pledging to give 99% of their Facebook shares to their philanthropic mission, later dubbed the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Today that stock is worth some $103 billion (plus the $4.2 billion they’ve already given away). If they follow through, and there are no indications they will not, CZI will emerge as one of the world’s largest philanthropic efforts, second only to that of Gates and his ex-wife, Melinda French Gates, and possibly bigger depending on Meta’s future performance.

Chan describes CZI as “an unbelievable opportunity.” It’s set up nontraditionally as a limited liability company that in addition to giving money away makes venture investments in for-profit companies that align with its goals. It also funds advocacy work. The LLC setup means Zuckerberg and Chan don’t get an immediate tax break, nor do they have to disclose its activities. But when they transfer assets from the LLC to CZI’s charitable foundation, which has $7 billion in assets (as of its most recent tax filing), the couple gets a tax deduction—and mandatory disclosure. CZI’s audacious goal is to help science cure, manage and prevent all disease by the end of the century. Full points for aiming high, but the reality of delivering treatments is complex. Chan is unfazed. “It’s rewarding to work on problems that people think are impossible,” she says.

To that end, CZI plans to build one of the world’s largest AI computing clusters for nonprofit life science research, trying to more completely model various human cells to understand how they behave when healthy and diseased. The Chan Zuckerberg Institute for Advanced Biological Imaging, which is based in Redwood City, California, is already developing new ways to view cells in high resolution to promote earlier disease detection.

Such expansive thinking has changed how Zuckerberg operates. As his CZI-backed entities study diseases, Mark three has embraced wellness in his own life to boost his productivity, exercising almost every day and sleeping a full eight hours a night. With jiujitsu and MMA, he’s engaging in combat, but in a respectful, more thoughtful way. And he’s clearly recognizing that his sins of the past decade might be washed away if he achieves even a fraction of what CZI has sworn to.

“Even if only a third of the things that you bet on work,” he says, “I think that still creates a ton of value in the world.”

This article was originally published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.