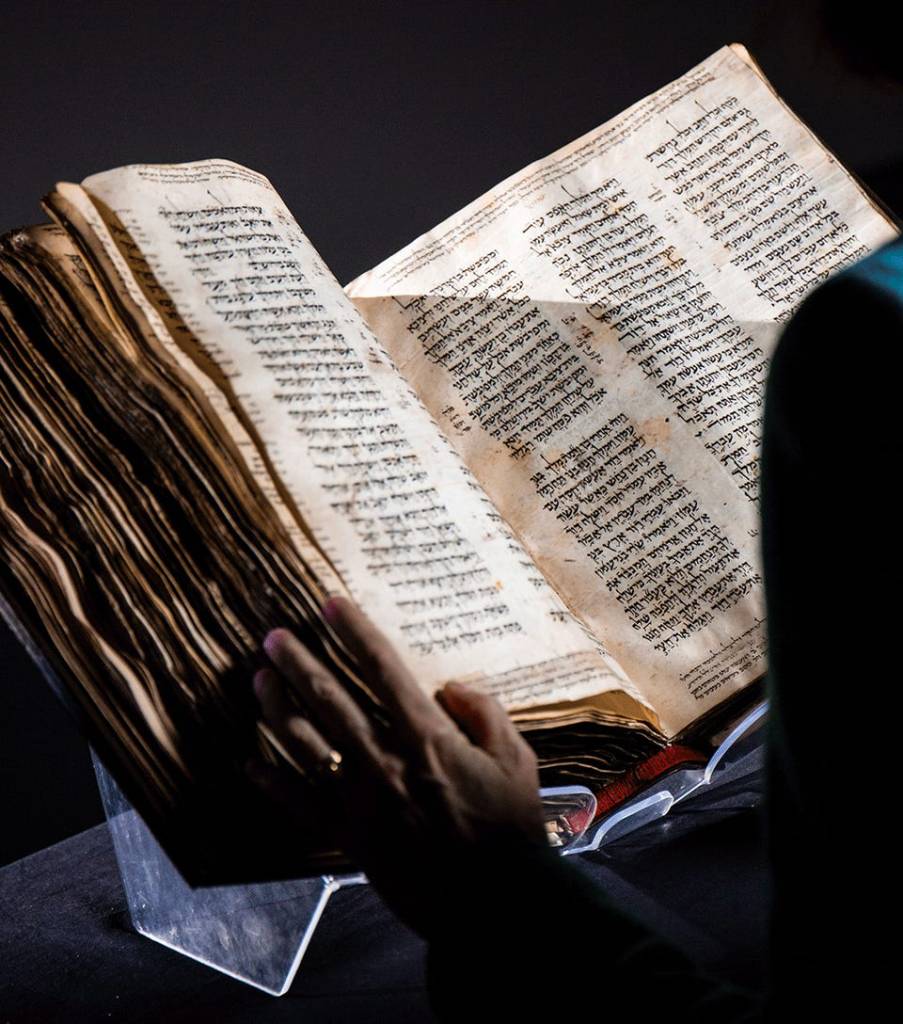

The Codex Sassoon, a 10th century Hebrew Bible, goes up for sale at Sotheby’s in May and could become the most valuable book ever sold at auction.

“It’s one of the world’s greatest treasures.” Sharon Liberman Mintz, a senior Judaica specialist at Sotheby’s, says of the Codex Sassoon, which goes up for auction in May. But for now, the thousand-year-old Hebrew Bible is stored in what looks like a supersized shoebox stuffed with paper, on a crowded table in a nondescript room at the auction house’s New York headquarters. Hardly a glamorous setting for one of the most valuable books in the world.

It’s not until Liberman Mintz and a colleague lift it—as gingerly as one can raise a 26-pound, six-inch thick stack of centuries-old parchment—that the true heft of the Codex apparent.

Already boasting the highest pre-auction estimate of a book or manuscript ($30 million to $50 million – AU$74 million), the Codex Sassoon could become the most expensive book or manuscript ever sold at auction when it hits the block this spring. That title is currently held by a first edition of the United States Constitution that sold for $43.2 million in 2021 to billionaire Ken Griffin.

Believed to have been written in the late 9th or early 10th century, the Codex Sassoon is particularly valuable because it’s the earliest, most complete Hebrew Bible in existence, containing each of the 24 books, including the Torah (or Pentateuch) the Nevi’im (or Prophets) and Ketuvim (or Writings). It also contains crucial vowel and cantillation marks that other Judaica manuscripts like the Dead Sea Scrolls lack—meaning modern-day Hebrew readers can understand it.

“We looked at the comparables and realized that there are no comparables,” says Liberman Mintz. “It’s a book that has such resonance for so many millions of people around the world, so we felt that the price was equivalent to its power.”

The Biblio File

The most valuable books, manuscripts or printed text ever sold at auction.

The Da Vinci Codex: Billl Gates purchased Leonardo’s scientific writings, known as the Codex Leicester, in 1994.

Francois Guillot/AFP/Getty Images

1. FIRST PRINTING OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION: $43.2 million

(Sotheby’s, 2021)

2. THE CODEX LEICESTER: $30.8 million

(Christie’s, 1994)

3. THE MAGNA CARTA: $21.3 million

(Sotheby’s, 2007)

4. BAY PSALM BOOK: $14.2 million

(Sotheby’s, 2013)

5. THE ROTHSCHILD PRAYERBOOK:$13.6 million

(Christie’s, 2014)

Source: Sotheby’s

For the Codex Sassoon, the May auction is the latest stop on its extraordinary thousand-year journey, which began with a wealthy patron, some 200 pieces of sheepskin and more than a year’s work for a single scribe. While the person who commissioned the Bible is lost to history, records inscribed in its pages over the centuries allow scholars to definitively trace later owners.

The first known sale of the Codex came in the early 11th century when businessman Khalaf ben Abraham sold it to Isaac ben Ezekiel al-Attar for an estimated 37 gold dinar, or enough money to feed a family of four for two years. He then bequeathed the manuscript to his sons with the condition that they never sell it.

The Bible eventually became the possession of a synagogue in Makisin, in present-day Syria, but the tiny village was destroyed between the 13th and 15th centuries and it was entrusted to a community member to safeguard it until the synagogue was rebuilt. It never was.

“All of those paratexts make this book exciting,” Liberman Mintz says of the provenance, “not only as a foundational object of Jewish and worldwide civilization, but also as a deeply personal object. We watch as it’s transmitted through the generations, and I find that really thrilling.”

The Bible survived the next five centuries until David Solomon Sassoon, a Bombay-born British scholar and bibliophile purchased it in 1929. Already a renowned collector of Hebrew manuscripts, books and other Judaica, Sassoon paid £350 for it (about $21,000 today) making it the fifth-most expensive text in his 1,274-piece collection. (The priciest was Maimonides’ Moreh Nevuchim, or Guide for the Perplexed, for which he spent the equivalent of $91,000 on and is now owned by the British Library).

Old Shul: One of the Codex’s early owners was the synagogue of Makisin in modern-day Syria, where it resided until the 13th or 15th centuries.

Sotheby’s

Since Sassoon (who died in 1942) purchased the Codex, it has appeared at auction only twice, both times at Sotheby’s: In 1978, when Sassoon’s heirs sold it to the British Rail Pension Fund for around $320,000 ($1.5 million today), and in 1989 when it fetched $3.2 million, or nearly $8 million today. And the winning bidder turned a profit almost immediately: The Codex Sassoon was sold to Swiss financier Jacqui Safra, of the Safra banking family, for an additional $1 million that same year, and it’s been in the 83-year-old Safra’s private collection ever since.

Given its provenance and rarity, the Codex Sassoon’s record $30 million to $50 million presale estimate was also fueled by blockbuster sales of other historical texts, including Leonardo da Vinci’s manuscript, the Codex Leicester, which Bill Gates purchased for $30.8 million in 1994, and the $43.2 million copy of the Constitution that Griffin outbid the Constitution DAO to acquire in 2021. But when compared to other ancient holy works, it’s in a league of its own.

Hand to God: When it comes to touching ancient texts, the gloves come off, says Sharon Liberman Mintz of Sotheby’s. The preferred method: Clean, bare hands.

Sotheby’s

Though 15 of its 929 chapters are missing, mostly from Genesis, that pales in comparison to another famed 10th-century Bible, the Aleppo Codex, which lost forty percent of its pages in the late 1940s under mysterious circumstances. The next best comparison is the Leningrad Codex, the most complete early Hebrew Bible—but that was written almost a century later.

The Codex Sassoon’s construction is largely to thank for its remarkable survival story. Its parchment pages will last forever, says Liberman Mintz, and because the manuscript is in book form—rather than scrolls—it helps preserve it. While the leather binding is relatively modern (Sassoon added it nearly a hundred years ago), and some pages have been mended, the book is largely the same as it was in the 10th century.

Its fine condition—combined with its vowel and cantillation marks—means that the Codex Sassoon is as readable as a modern Bible, good news for the thousands of visitors Sotheby’s expects on its ongoing international tour. In London, where it was shown from February 22 to 28—its first public display in more than forty years—about 800 visitors a day jostled for a view (though attendance dropped by half on the Sabbath. “It rested,” jokes Liberman Mintz.).

The next stops for the Codex are Tel Aviv, Dallas, Los Angeles and, finally, New York, where it will spend the last weeks leading up to its sale. As for who might be the next owner of the Codex Sassoon, Liberman Mintz says Sotheby’s has received equal interest from private individuals and public institutions around the world. “Private ownership does not preclude public access,” Liberman Mintz is quick to note, as institutions will often court private investors to buy big-ticket items and donate them (one obvious benefit: the tax write-off).

“I think everything is possible at this point,” Liberman Mintz says of the historic May sale. “This book is deeply powerful. To be able to hold something in your hands that’s a piece of history, not just Jewish history, but is a foundational text of worldwide civilisation…it’s electrifying.”

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.