The University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies joined forces with CSIRO, the Natural Resources Foundation, the Great Southern Reef Foundation, and Google Australia to study, sequence and rewild giant kelp.

‘Ideas to Save the Planet’ featured in Issue 14 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

The Problem

Giant kelp in the Great Southern Reef is being decimated by warming, nutrient-poor oceans impacting marine ecology and the $10 billion in economic value derived annually from the reef through fisheries, tourism and recreation.

The Solution

World-first AI and satellite imagery to identify heat-resistant underwater giant kelp, genomic research to cultivate heat-resistant varieties that can be rewilded into oceans in eastern Tasmania.

The impact that climate change is having on Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef is well documented. Yet the deterioration of the Great Southern Reef – bordering five Australian states, spanning 8,000 kilometres of coastline, and generating $10 billion for the Australian economy annually – gets much less attention.

The cooler temperatures of the Great Southern Reef mean there is no coral. The lifeblood of the ecosystem in WA, SA, NSW, and Victoria’s reefs is kelp. In the ocean around Tasmania, giant kelp can reach 35 metres in height and, in ideal conditions, grow 50 cm each day.

Giant kelp is not only essential to the health of the Great Southern Reef but also to reefs all over the world. According to the Great Southern Reef Foundation, it is a foundation species and the underwater equivalent of a forest of trees that modify the environment and maximise biodiversity.

The strands attach to the seabed and reach for the sunlight on the ocean’s surface using air-filled ‘bladders.’ Giant kelp is out of sight, and its reputation as a slimy, smelly seaweed keeps it out of mind.

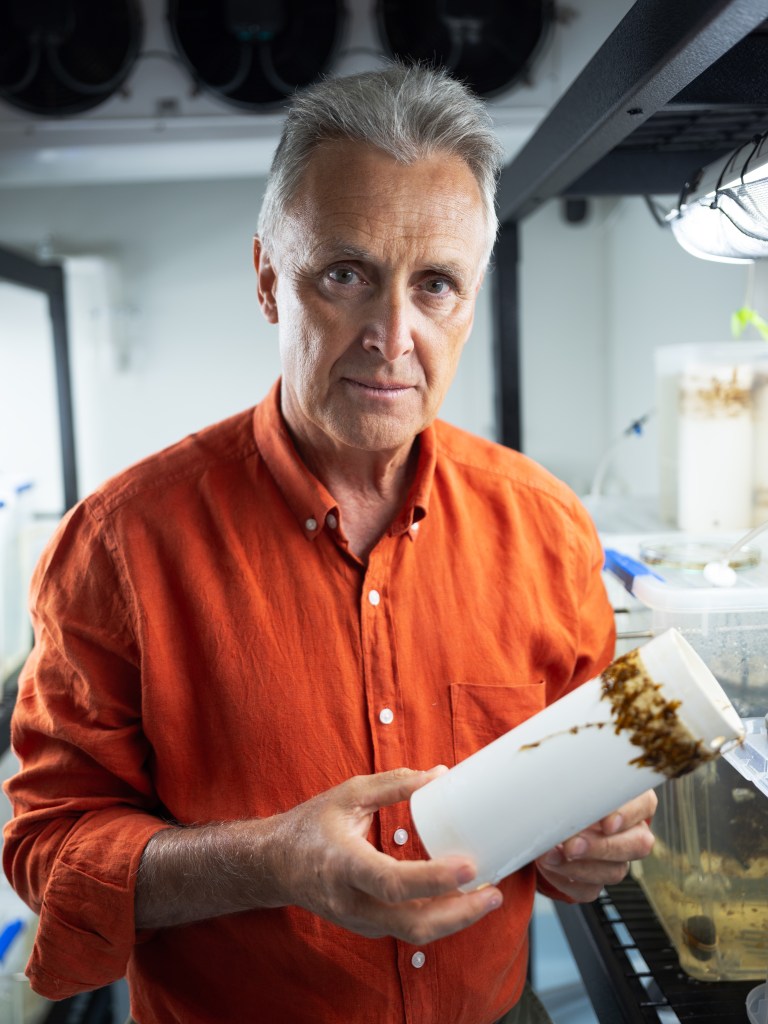

Professor Craig Johnson is a marine ecologist with the University of Tasmania working to change that perception. “We’ve lost 95% of these giant kelp forests,” says Johnson. “If we lost 95% of the Daintree Rainforest, it would be a very different sort of community response – because the Daintree is not out of sight, out of mind like underwater kelp is.”

Professor Johnson is a kelp ecology expert who has worked in the northern and southern hemispheres on coral and temperate reefs. Born in Tasmania, Johnson returned to his island home to be at the epicentre of giant kelp regeneration efforts. “Scientists worldwide are watching us carefully. The rate of warming in eastern Tasmania is three times the global average – the impact happening here is a bellwether for other regions,” says Johnson.

Ocean temperatures around the Tasman Sea have risen by two degrees Celsius over the past 60 years, according to CSIRO. The global ocean surface compounds the problem in the Great Southern Reef, and deeper currents are shifting south.

Australian organisations partnering to rewild giant kelp

The University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) has joined forces with CSIRO, the Natural Resources Foundation, and The Nature Conservancy in Australia to study and rewild giant kelp. Juvenile kelp is being grown in local hatcheries and out-planted along the east coast of Tasmania.

In a world first, AI and satellite imagery are being used to locate surviving kelp forests in an area spanning 7,000 km2. Google’s DeepConsensus and DeepVariant AI tools are helping to analyse what makes these portions of giant kelp heat resistant. The genetic sequence of those varieties is studied in a CSIRO lab in Hobart.

“One of the main focuses of this project is to understand why some giant kelp can withstand temperatures up to four degrees higher than they used to. And to introduce this into the restoration plots,” says Dr Anusuya Willis, the Director of CSIRO’s National Algae Culture Collection. “This will breed in resilience to heat waves so that these populations can live through the summers of now and the future.”

Willis’ work would not have been possible without advanced technology.

“This huge amount of data that we’re producing – full genomes, reference genomes, hundreds of samples, multiple samples in the labs at different temperatures, different conditions. We’re producing terabytes of data, and Google AI platforms are helping to analyse it and tease out the details,” says Willis.

Leah Kaplan is Google APAC’s business sustainability lead, facilitating Google’s participation in the project through its Digital Futures Initiative. “In the past, scientists flew aerial surveys and took pictures of the kelp. Satellite imagery captures more than the visible spectrum; we can detect more than you can see with the naked eye,” says Kaplan.

“We’ve been late to the party in terms of some of the old methods in the restoration space, and we’re now at the leading edge,” says Dr Scott Bennett, a senior researcher at IMAS.

Bennett says the work the consortium of organisations is doing to restore kelp is invaluable. “Our oceans are warming fast, forcing the conversation along. We have restoration techniques underway and can now do things at scales that haven’t been done in many places around the world.”

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.