The Problem: Filling the wind and solar intermittency gap to reach net zero by 2050.

The Solution: Drawing on oil and gas industry expertise to create reliable renewable energy from waves.

It was 3am on an offshore construction vessel stationed on the north west shelf of WA when Simon Renwick realised he had solved the long, elusive puzzle of how to harness wave energy effectively.

“We were putting a cylindrical floating structure in the water with a crane, and it started heaving up and down five meters out of the water, and everyone was kind of panicking,” says Renwick.

The instability set alarm bells off with some of the 150 crew living on board the ship. “I was like, no, I know exactly what is happening here. It resonated – an effect and a set of equations I understood from my uni days.”

Renwick led the team to fix the problem by filling the floating structures with water to sink them and stop them from resonating.

“After that, I realised that if we had two thousand-ton cylinders sitting next to each other and one was moving and one wasn’t moving, that’s a really good way to harness wave energy.”

Renwick’s analogy to describe the renewable energy innovation he uncovered is akin to a rising – but choppy – tide non-simultaneously lifting all boats. “It’s like having two different types of boats next to each other when a wave goes past. They never move together. They always move differently from each other. Our floating structures weigh a thousand tons each, so massive forces are involved. Our job is to convert that relative motion between the vessels into electricity through a linear generator,” says Renwick.

It turns out that the concept was the subject of his university thesis, undertaken 12 years before.

“In 1998, I did my honours research in civil engineering on the hydrodynamic motion of oil and gas facilities. Those hydrodynamic equations never left my brain, despite my best efforts,” says Renwick.

Fifteen years after that fateful night off the coast of WA, Renwick is now the founder and CEO of Perth-headquartered wave power generator firm WaveX. “We believe we’ve got the world’s first scalable wave energy converter that will survive all the storms that are thrown at it, which have been a large part of the mediocre performance of wave energy until now,” says Renwick.

“Our window is three to five years, and by including wave energy as the gap filler, you can reduce the cost of electricity to the grid by 50%. It’s the absolute game-changer.”

Simon Renwick, WaveX founder

A part of the WaveX secret is the placement of the wave-harnessing technology. “We have no underwater electrical or mechanical moving parts, which is quite different to how everyone else approaches wave energy,” says the WA-born entrepreneurial engineer. Those were also lessons he learned in his oil and gas days.

“Stuff breaks when it goes underwater. Those guys have an unlimited budget to ensure stuff doesn’t break, and it still breaks. We’re a different market and commodity, and we don’t have unlimited budgets, so we just said no underwater moving parts.”

Instead, the underwater electrical and mechanical moving parts are stored inside a water-tight steel-welded hull.

“We have two big floating tubes that weigh 1000 tonnes each and have iron ore in the bottom so that they sit vertically in the water. They’re about 10 metres in diameter and 30 metres deep. We join those two structures together but still allow them to move freely relative to each other; that’s effectively our IP,” says Renwick.

The watery solution to a sticky, blue energy problem

Tapping into the motion of waves to create energy dates back to the late 18th century. The first wave energy patent was filed in 1799 by French civil engineer Pierre-Simon Girard.

“Between 1856 and 1973, over 340 British patents on wave energy were filed, yet significant progress did not occur until the 1970s,” according to a report issued in November 2024 by the Australian government’s Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre.

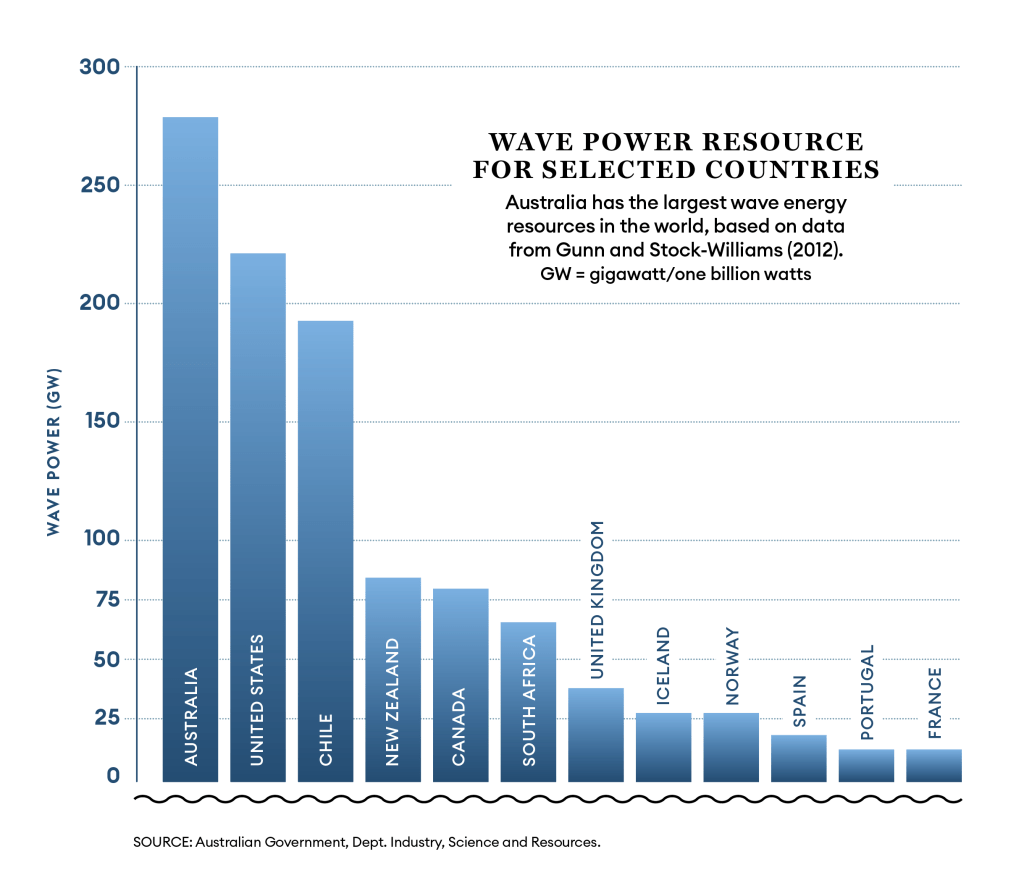

“In Western Australia, we’ve got the best wind, sun, and critical minerals. We also happen to have the best wave energy resource globally.”

Simon Renwick, WaveX founder

In 1974, a scientist at the University of Edinburgh published a seminal paper demonstrating 80% absorption of incoming wave energy using a tool called the ‘Salter Duck.’

Wave energy was on a roll, but by the 1980s, oil prices had declined and funding for alternative energy innovation dried up.

Tweaking oil and gas technology to go green

R&D in the oil and gas-rich North Sea near Scotland continued, however.

Shell had pioneered the world’s first ‘spar platform’ in the Brent Oilfield in 1976. The partially submerged, 300-metre cylinder included a platform that peaked above the ocean’s surface and storage of oil in the deep sea. The Brent Spar as it is known to this day, was a design influence for the cylinders that WaveX is now building to procure renewable energy.

Some 25 years after the spar platform was pioneered, innovation in the North Sea returned to alternative energy sources.

The European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) was built just off the Scottish north coast in 2003, committed to the real-world exploration of wave and tidal energy. Here, Renwick spent 2005 and 2006 studying wave energy as one of EMEC’s earliest employees.

Today, the Scottish EMEC is the benchmark for similar facilities around the globe, inspiring similar facilities in South Korea, the US, France, Ireland and Portugal.

These global marine energy centres are where WaveX plans to deploy its technology.

Wave energy meets sub-sea cables en route to land

Renwick says that exposure to oil and gas operations has also given him insight into developing the WaveX business model. “Our pathway to commercialisation involves 16 wave energy connection points built by governments worldwide, who understand the value of wave energy,” he says.

“They have already got environmental approvals and the power cable installed. They’re already connected to the grid, which are the things that take all the time. Almost none of these facilities are currently used.”

Once WaveX has completed its proof of concept in Albany at the University of Western Australia test site, it will build a larger installation at an undisclosed location. “Our Albany one is about 12 metres wide and 40 tons. Our big one, is around 45 metres wide and weighs around 1300 metric tons of steel,” says Renwick.

When the technology is ready to be deployed into the global Marine Energy Centres, WaveX will operate as an OEM. “We’re an original equipment manufacturer effectively. We still work with power developers, but instead of them going and buying wind turbines for their offshore project, they come to us and buy wave energy devices.”

Renwick’s firm will, in turn, pay the marine energy centre a fee. “We pay them an amount like a leasing fee effectively, which keeps the lights on for them and gives them a return on their investment.” Setting up the facilities is a cost-intensive process. The Pacific Marine Energy Center off the coast of Oregon cost $24 million and can service companies producing electricity from waves and offshore wind turbines. “These 15 test sites recognise the value of wave energy as this gap filler, and they’re a little bit ahead of the market; a lot have been sitting there for some time.”

Australia’s, and specifically WA’s, competitive advantage, Renwick says, is five-fold: its abundance of renewable natural resources, oil and gas talent and insight, maritime fabrication expertise at Henderson, and proximity and strong trade relationships with Japan, South Korea, and other Asian countries.

“In Western Australia, we’ve got the best wind, sun, and critical minerals. We also happen to have the best wave energy resource globally,” says Renwick. “We can get this going quickly, relative to, say, trying to establish a nuclear industry. Our window is three to five years, and by including wave energy as the gap filler, you can reduce the cost of electricity to the grid by 50%. It’s the absolute game-changer.”