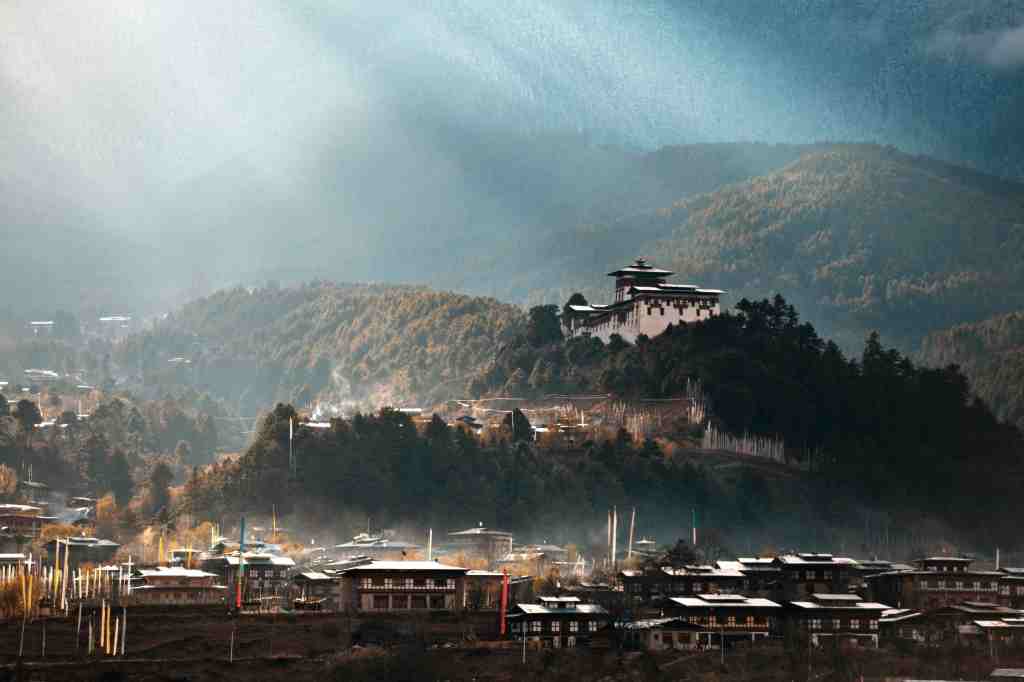

Australia is suffering from a mental health crisis. Suicide and self-harm are increasing, and some are linking it to technology. Meanwhile, in Bhutan, there is a nuanced vision for creating happiness but also, a push to digitalise. It is also seeing a serious brain drain. Where are they going? To Australia. Forbes Australia’s Stewart Hawkins was granted rare access to the kingdom and sat down with the country’s secular leader and a senior spiritual scholar to explore that dichotomy.

One of the first things the Bhutanese Prime Minister says to me is that he feels the world-famous concept of gross national happiness has been misrepresented or misunderstood.

The 54-year-old Dr Lotay Tshering, a surgeon by trade, is sitting in a plush armchair in the Ceremonial Lodge at Paro airport. He seems tired, and his rugged, strong-featured face looks slightly the worse for wear, having just jumped off the plane from New Delhi.

Dressed in a traditional Gho, he speaks deliberately and with a calm intelligence, insisting he will answer “any question under the sun” during our interview, wanting me to take away the “purest and truest” information.

I can hand-on-heart say no other politician has made that promise to me.

I start by pointing out that Australian people – despite being rich (the richest in the world, on a median asset-ownership basis according to a 2022 Credit Suisse report) – are suffering a severe mental health crisis and are, quite often, miserable. Bhutanese, on the other hand, with a GDP per capita of US$3,200 per annum, seem to be, well, happy.

I asked him why?

“If you want to believe that money will bring happiness, or the richer you get, the happier you will be, then I think this is a good question. But for myself, I don’t think money will make you happy,” Dr Lotay replies.

“When I say this though – in the context of gross national happiness – we do not mean [happiness in terms of] emotional mood, how happy or elated you are, or excited you are, that is not the kind of happiness we are talking about.

“[It’s] how peaceful you are, how content you are, how settled and how at home you feel wherever you go. How you reason out life, how you want to do more with less. These are values. When you say happiness, it’s not just mood.

“Contentment depends on your needs and wants in life. Your desire in life. If you don’t know how to put a check on your desire in life, you will never be content.”

Gross national happiness, as a governance concept, was introduced to Bhutan in 2008. It has an index based on survey data, technically a multidimensional poverty index, according to the Asian Development Bank. Statistics are compiled under nine domains: living standards, health, education, environment, community, time use, psychological well-being, governance, and culture.

“The index ranges from 0 (if all surveyed individuals have insufficient achievement in all nine domains) and 1 (if all surveyed individuals have sufficient achievement in all nine domains),” the Bank says.

So, far from being a simple call to be happy with your lot, the thought process behind gross national happiness, according to Dr Lotay, goes deeper, acknowledging people want to be richer and have the right to be, but understanding there is an environmental and social cost to that wealth.

He talks about the concept of “intergenerational equity”, something protected in the country’s constitution, which demands a minimum of 60% of the country remain under forest cover (72% currently is). If resources are to be tapped, then it must be done in a way that does not disadvantage future generations.

“Outside Bhutan, [people] talk about… the Happiness Kingdom. While we are happy to hear that, I am unsure how to take it because it’s always being connoted with Bhutanese being happy with less. Bhutanese are okay to be poor but happy,” Dr Lotay says.

“We are human beings. We also want to be rich. We also want to have more. But in our own time. In global terms, I would say we want to be sustainably rich. We want to be sustainably happy. The happiness that we have, the contentment that we have, the pride that we have as Bhutanese must be sustainable. We should be able to pass it down to our children.”

It’s worth mentioning Bhutan is currently carbon negative. It sinks three times more carbon than it emits, according to Dr Lotay. [The World Population Review currently lists only three countries as carbon negative – Bhutan, Panama and Suriname.]

Grim reading

While it’s one thing to make an observational assessment based on a short time in a place, it’s another to crunch the numbers. However, any assessment of “happiness” is most likely based on survey data, and it’s challenging to find an apples-to-apples comparison in that space.

Dr Peter Baldwin is a Senior Research Fellow and Policy Research Manager with Sydney’s Black Dog Institute. He also suggests happiness is a difficult concept to pin down as it means many different things to different people at different times.

“There’s a big difference between happiness as a construct and how we think of happiness in our society,” he says.

“Mental illness is not just necessarily the absence of happiness, and people living with mental illness can experience times when they describe themselves as quite happy and content. So, they’re not necessarily mutually exclusive in that way.

“My background is in cognitive neuroscience, and you can’t look at a human brain and say, okay, so that’s in a happy or sad state. Happiness is just something that we label and put on our experiences, and that label varies across time and place. For us, it’s much more about that person being able to live a high-quality and meaningful life.”

Dr Baldwin maintains that anxiety disorders are the most common mental-illness complaint amongst Australians, followed by depressive disorders or mood disorders.

“The happiness that we have, the contentment that we have, the pride that we have as Bhutanese must be sustainable.”

But one of the worrying trends is the increasing incidence of self-harm in young people, particularly in young women. (As an aside, self-harm is considered distinct from suicide – it is, however, related because it can result in death.)

Any symptom that results in physical injury stresses the health system because people need to present to emergency departments, and they need immediate care.

When I quizzed Dr Baldwin about what he thought was the cause of this increase in incidents of self-harm, he was understandably cautious about giving a definitive answer.

“There are some variables associated with the pharmacological side of things – the availability of some drugs – particularly the availability of bulk paracetamol. Our research suggests that it is a risk,” he says.

“Another thing that we’ve seen is the representation of self-harm on social media. Unfortunately, human brains are designed so that when they experience a stimulus repeatedly, they habituate to it, and it becomes normal. So young people seeing images and even sometimes tips on how to self-harm either in a safe way or in a way that mum and dad won’t find out, that’s potentially related to it.”

Dr Balwin maintains what we need to be happy and healthy is predictability in our environment. We need to have a sense of hope that we’re going to have goals that we can achieve and agency in our future.

He says a lot of young people had that taken away at a critical developmental period during the pandemic, and it affected their social, cognitive and educational development.

Intriguingly, he asserts that much of our brain’s anxiety is also centred around uncertainty and unpredictability, and we see that in any organism with a nervous system.

“Poor people are still poor [despite the wealth in Australia],” he says. “There is still a lot of wage and food uncertainty.

So, I think that [while], on average, on one metric, we are doing well, there’s certainly a lot more to life and a lot more to happy, healthy brains than material wealth, that’s for sure.”

He outlined three key needs for mental wellbeing:

- Autonomy – we need to have a choice in what we do

- Freedom – we need to learn, get better and make a contribution to the community

- Relatedness – to be connected with other people in a meaningful way

He says some countries do a brilliant job meeting citizens’ psychological needs without much material wealth. In his role at the Black Dog Institute, he’s been trying to encourage the Australian Government to measure our psychological needs and understand how we increase those rather than our material wealth.

“My recommendation to the government is if we started to look at inequities between things like autonomy or relatedness, we might start to see that certain groups are simply more able to achieve their psychological needs than others due to a range of factors. If we’re able to balance that out, then we probably will see people start to thrive,” he says.

Dr Baldwin says he’s recently wrapped up a large longitudinal study of young people, and the results show a clear relationship between the use of technology and the increased number of depressive episodes that young people experience. But the data is unclear on whether increased screen time leads to increased depression. It’s equally likely that young people experiencing low mood are increasingly spending time online.

“I think what they’re doing is they’re seeing content that’s making them perhaps a bit more depressed because, unfortunately, people when in [a] depressive episode, develop this negative stimulus bias where they just are more attracted to more negative stimuli.”

“If a Bhutanese does well on this planet, it is a Bhutanese doing well. That is to our pride.”

It becomes a self-fulfilling feedback loop. Ergo, when you’re in that state, trawling the internet will probably make you worse.

“Talk to the parent of any teenager, they’re highly emotional creatures, but they’re not quite there in terms of their brain development, where they can think long term, and they can come up with alternate solutions for problems, which is one of the reasons why adolescence is such a risk period for self-harm and suicide. They’re always coming up with these permanent solutions for very temporary problems,” he says.

But for adults, Dr Baldwin admits we’re still in a situation where women are more likely to attempt suicide, but more men are likely to succeed.

The reading is grim, at least in Australia. According to the Government’s Institute of Health and Welfare data for 2019–2021, suicide was the leading cause of death among people aged 15–24 (36%). For people aged 25–44, it was also suicide (22%). Perhaps most shockingly, it was the 5th leading cause of death in children aged between 1 and 14. And these figures included land transport accidents.

According to Beyond Blue, more than 3,000 Australians take their lives each year and 65,000 attempt suicide.

[As a comparison, the road toll in 2022, according to the Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Economics, was around 1,100 fatalities.]

Falling back on World Health Organisation data, Bhutan’s life expectancy in 2019 was 73.1 (global average 73.3), and Australia’s was 10 years higher at 83. However, self-harm didn’t factor as a leading cause of death across all ages in Bhutan in this data set. It came in at number nine for Australian males (not, however, for Australian females), following mainly aging-related diseases.

This is not to suggest that the Bhutanese are immune from the ravages of circumstance, just that they may have a better way of dealing with it.

On the flip side, though, a report in The Lancet, published in March this year, found that during the pandemic, “a rise in depression and anxiety had been reported in Bhutan. Depression rose from an average prevalence of 9 per 10,000 between 2011 and 2019 to… 32 per 10,000 in 2021. Similarly, anxiety rose from an average prevalence of 18 per 10,000 to… 55 per 10,000 in 2021.”

Interestingly it also found that: “Stigma and discrimination towards mental health disorders discouraged mentally distressed people from seeking care.”

The report acknowledged the government began a “range of interventions including home delivery of medicines and tele-counselling to people in need of urgent mental health care” but that the care could be further improved.

Why are young people leaving?

Happy or not, Bhutanese are leaving their home country in droves. And guess where they’re heading? To Australia. Media reports have suggested that 1.4% of the Bhutanese population have been granted visas to Australia since June last year.

Much of that is to take advantage of Australia’s education system – but there’s also a large contingent seeking better material opportunities. When I questioned him about it, he insisted it was important to build infrastructure and opportunities to encourage them to return, and he saw a positive side to the situation.

“We have more Bhutanese leaving Bhutan in [the] last two, three years compared to pre-pandemic days. We agree with that. Most of them are in Australia. Again, we agree with that,” he says.

“[But] that only points to the fact that we are all human beings. It’s [the] nature of a human being to chase opportunities. [However] many Bhutanese are leaving because… now [the] Australian economy is opening [and] you need [a] labour force.

“Are we worried? Oh yes, sure. But will we have to do anything to stop them from going to Australia or other similar economies? Absolutely not. Because wherever one goes, they will always be true Bhutanese. If a Bhutanese does well on this planet, it is a Bhutanese doing well. That is to our pride. Wherever they go now, looking for opportunities, gaining some extra experience, skills and knowledge, we are very happy.”

Having said that Dr Lotay acknowledged that Bhutan should create opportunities

for migrants to use the experience they have gained overseas and to invest back home. He hopes that should “mostly bring them physically back willingly”.

Dr Lotay insisted the best way to develop the Bhutanese economy sustainably and rapidly was a push to “digitise” the country. A national Digital IT Act was recently introduced to parliament, and Dr Lotay says the country has introduced ICT (Information and Communications Technology) as a “third language in all the schools”. [The first is the national language, Dzongkha, and the second is English.]

This is all good, except for a country that guards its culture so carefully. Opening up digitally is fraught with danger.

Dr Lotay agreed: “Fearing dangers if you don’t embark onto those avenues, we will be left behind. We must be able to take advantage. Then to have the resilience to identify and fight off the risk.

“Everything must be agile enough to adapt to the need of the hour. I have no choice about choosing between my culture versus going digital. But we don’t have to pick one side. We can digitise our culture. We can digitise our mindset. As long we remain true Bhutanese.”

Ancient roots of happiness

While the country is rapidly digitalising, it must be emphasised that the politics and practicalities of gross national happiness are inextricably linked to Bhutan’s spiritual and philosophical infrastructure. This dates back to when the Buddhist saint Guru Rinpoche or Padmasambhava (the lotus born) brought teachings to the region.

I was lucky to spend several hours with Buddhist scholar and reincarnate lama Mynak Rinpoche. (He was recognised at the age of two as the reincarnation of Wonpo Tulku of Rikhud Monastery in Minyak, Eastern Tibet. The title Rinpoche means precious one in Tibetan.)

We spoke about many things, political, global, and personal, including the untimely and tragic death of my brother. But he kept coming back to one point.

It’s something the Dalai Lama espouses as well, that the prime purpose in life is to help others. And if you can’t help them, at least don’t hurt them.

He stressed that in Mahayana (or Great Vehicle) Buddhism, practised in Bhutan, it is vital that you should strive to attain enlightenment for the sake of the liberation of all sentient beings from samsara (or suffering), not for yourself.

One of the highest callings is, after attaining enlightenment, to come back to samsara in human form and help others achieve the same state. It is an outward rather than inward-looking school of Buddhism, a socially engaged philosophy that sometimes is lost when teachings are brought West. (Important to note that the last observation is mine, not his.)

Bhutan fast facts

Population: 770,000

Land mass: 38,394 square kilometres (Slightly smaller than Switzerland at 41,285 square kilometres).

Situated between China and India in the Eastern Himalayan region.

Forest cover: 71%

Highest point: Gangkhar Puensum. 7,570m

Capital: Thimphu.

Elv. 2,334m

Official language: Dzongkha. (A Sino-Tibetan language which is written with Tibetan script).

Government: Democratic constitutional monarchy (since 2008).

Current monarch is His Majesty King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck (Dragon King).

Economy: Agriculture and forestry are primary components.

Key exports are tourism and hydropower. The economy grew by 4.3% FY21/22, expected to post a growth of 4.5% in FY22/23. Current account deficit was at 33.1% of GDP FY21/22.

Bhutan is described by the World Bank as a “lower-middle income country”.

Sources: DFAT, World Bank

If you or anyone needs help: Lifeline 13 11 14, MensLine Australia 1300 789 978 , Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467, Beyond Blue 1300 22 46 36, QLife 1800 184 527

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here.