Melanie Cooper, first female chair of Coopers Brewery, on keeping the largest Australian-owned beer maker in the family.

This article was featured in Issue 11 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Coopers Key Facts

- Coopers have about 5% of the Australian beer market and are the largest independent brewer. They produce about 100 million bottles and 60 million cans of beer a year.

- Coopers made $28.5 million profit last financial year, up $1.5 million on the previous year, from revenues of $287 million, which had risen 5.9% in 2021-22.

- Keg sales were up, but packaged beer was down in a market that hadn’t yet returned to pre-COVID-19 levels.

- Coopers recorded total beer sales, excluding non-alcoholic beers, of 77.6 million litres for the 2023 financial year – a 2.3% fall on the previous year’s volumes.

Melanie Cooper grew up over the road from the family business in Leabrook, Adelaide, and would spend time mucking about in the brewery on weekends with her older brother Tim and their cousin Glenn Cooper while her dad, managing director Bill Cooper, was working. She’d ride her bike through the grounds on her way to school, saying hello to workers.

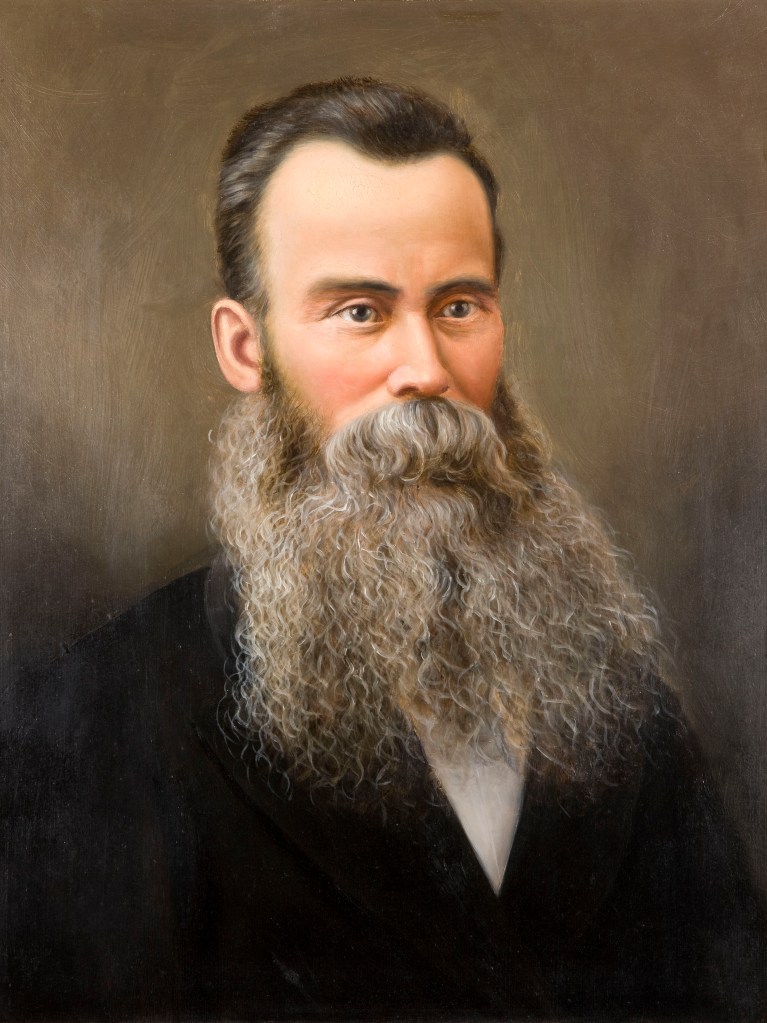

The brewery founded by her great, great, great grandfather Thomas Cooper in 1862 was in her blood, she says, but the minor brewer wasn’t in her future – she wanted to be a physiotherapist.

The brewery was still firmly in family hands, but ownership was growing increasingly diffuse as shares spread among the descendants of Thomas’s four sons, plus a quarter share owned by the South Australian Brewing Company, the state’s largest brewer with its West End lagers.

Being a numbers person, Mel Cooper was persuaded that economics and accounting might suit her better than fixing broken bodies. She was in a tiny minority of women studying economics at the University of Adelaide in 1980 – she recalls it might have been as low as 5% – but the guys in her cohort embraced Coopers Sparkling Ale on tap at the Union Bar more enthusiastically than the rest of the population.

“And as my father said, ‘I am Bill Cooper of Coopers brewery. If I sell these shares, I just become Bill Cooper, owner of condominiums.’”

Melanie Cooper

“When I grew up, Coopers’ beers were not as popular as they are today. And, in fact, it was almost embarrassing to say you were a Cooper because they’d be like, ‘Uh, not that heavy stuff with all that gunk in it.’ And so I really didn’t disclose that I was a Cooper from Coopers Brewery.”

Thomas Cooper had brewed his first batch of ale 20 years before the first German-style lager was brewed in Melbourne in 1882, and for ales, it had been all downhill from there as Australians began their love affair with the lighter lagers.

After university, Mel Cooper worked for Price Waterhouse as an auditor but was bored. After a few years, she pursued a job with an American merchant bank that was setting up in Australia after the deregulation of the financial system.

“My father said, ‘Just before you take that offer, would you come and speak to us about maybe being an accountant at the brewery, and we’ll match whatever they’re paying you.’”

She figured that, as an auditor, she’d seen so many systems – good and bad – that she might have something to offer the family business. So, in 1985, she became the first female family member to work at the business and the first of the fifth generation.

When she arrived, debtors and invoicing were handled by a mainframe computer, but everything else was still on paper. She helped the chief financial officer get all the other functions onto other computers. At the same time, her father, Bill, and cousin, Glenn, worked on making their brew fashionable again, especially outside of South Australia – even succeeding in the US before a rising Australian dollar made exports too expensive.

In 1989, she added “company secretary” to her duties and got to attend board meetings. But in 1993, her husband was posted to Brisbane for his job. “By then, my brother Tim [a medical doctor] had come into the brewery as a brewer, and I said to my father, ‘Unfortunately, we’re gonna have to go to Brisbane.’ And he said, ‘Oh, no, no, no, no. That’s ruined all my plans.’”

And so, off she went. Two children came along soon after, before the marriage failed and she returned to Adelaide, a single mother now, picking up part-time accounting work to pay the bills.

In 2001, her brother Tim, who was about to take over as CEO, asked her to return to the company. With the kids now in primary school, she jumped at the chance. “I was able to then look after my kids in a way that, I suppose, was better for them.”

The family had by then bought back the South Australian Brewing Co.’s shares, but it wasn’t long before the company faced its greatest existential crisis. In 2005, the then New Zealand-owned Lion Nathan (which had a few years earlier swallowed SA Brewing) launched a takeover bid.

While Coopers was privately owned, because it had more than 50 shareholders (it had about 120 at the time), it was a public company, so, under the Companies Act, it had to receive the offer and respond.

The company had been set up in the 1920s such that shares had first to be offered to descendants of Thomas before they could be sold elsewhere. Their value was set by internal mechanisms which, in 2005, had the price at $45 a share.

Lion was offering $260 a share, valuing the company at $352 million.

It stood to make the dispersed web of cousins wealthy. However, the small group of family members at the company’s core resisted and rallied support from the wider shareholder groups.

Lion upped the offer to $310 a share and took out full-page newspaper ads quoting interstate business journalists astonished that the family was resisting.

“As many of the shareholders said at the time, the money doesn’t mean anything to us,” recalls Cooper. “This is more about our history, heritage, and sense of identity … And as my father said, ‘I am Bill Cooper of Coopers brewery. If I sell these shares, I just become Bill Cooper, owner of condominiums.’”

In the end, two per cent of shareholders did sell. But Lion didn’t get a single share. Other family members bought them at Lion’s offer price. The bid was voted down by 93.7% of shareholders.

“The immediate feeling amongst the larger shareholders was relief and a sense of pride,” recalls Cooper. “We got very much closer to our shareholders. And we’ve worked out that it was really important to keep them engaged. Our AGM is a social event. We’ve had quite a few dinners. Pre-COVID-19, we were having sixth-generation events every 18 months to keep them informed and engaged. “It’s brought us closer together as a group.”

One effect of the bid was to spread the shareholdings even thinner, says Cooper. “A lot of family members were so proud of the shareholders and what the brewery had achieved, that grandparents gave their grandchildren shares, parents gave their children shares. Suddenly, we had a proliferation of new shareholders holding small parcels. They’re engaged, enthusiastic, loyal and interested.”

There are now more than 200 owners. The shares are trading at $400 and paying about $6 a share in dividends.

Cooper says she doesn’t know what percentage she owns, but it would be in the low single digits.

Australia’s Top 10 Beer Brands

| Rank | Beer |

|---|---|

| 1 | Great Northern Brewing Co … [Asahi] |

| 2 | Carlton Dry … [Asahi] |

| 3 | XXXX Gold … [Kirin] |

| 4 | Coopers |

| 5 | Victoria Bitter … [Asahi] |

| 6 | Corona … [Asahi] |

| 7 | Tooheys … [Kirin] |

| 8 | Hahn … [Kirin] |

| 9 | Pure Blonde …[Asahi] |

| 10 | Asahi … [Asahi] |

Four main family groupings control most of the company. “Tim and my family are significant shareholders. Glenn’s family is a significant shareholder.” The family of their father’s first cousin, former chairman Maxwell Cooper, is also a significant grouping, with Maxwell’s son-in-law Cam Pearce holding a seat on the board. Board member James Cooper – the first sixth-generation family member on the board – represents the fourth main group.

“A couple of those groups are close to 20%, but nobody has a controlling interest,” says Cooper.

Cooper knows more of them than most through her role as company secretary. “I would have emailed all of them. I might not have met all of them, but I’ve learned a lot about their families and about them. It’s very much a family business in that way.”

There are so many shareholder family members now the company has a policy of not employing them or their children as school leavers. “We say, go out and get a career before you think about coming into the brewery. You will make your mistakes on the outside.”

The Coopers board now comprises Mel Cooper, 63, her brother Dr Tim Cooper, 68, Dr James Cooper, 70, Glenn’s son Andrew Cooper, 41, in-law Cam Pearce, 66, and independent director Rob Chapman.

Cooper says the goal is to get more people to try the product in a declining beer market and to bring the next generation of the family through.

They’re building a $60 million visitor centre at Regency Park brewery in Adelaide where they will have seasonal beers on tap and a Coopers whisky, the first batch of which is already aging in barrels. “We want to bring in the next generation and foster their growth in the company because we’re all getting older, and it’s nice to think we’ll be upskilling them to be the next custodians of our brand.”