After a turbulent ending to her tenure as Australia Post’s CEO, Christine Holgate has re-emerged as the driving force behind the resurrection of staggering logistics giant, Toll Global Express. Since taking the helm in September 2021, Holgate has increased revenue by 16 per cent and halved staff turnover with the promise of profitability in the upcoming reports. And she’s done it all with an eye on the group’s enormous footprint, rolling out EVs and rail.

Christine Holgate will share her full story live at the Forbes Business Summit. You can secure your ticket here.

It all started in 2021. Christine Holgate was living a nightmare. Gagged from speaking about the imbroglio that saw her ousted from the top job at Australia Post, she endured dark suicidal thoughts, stewing that if she’d just given her executives $150,000 bonuses instead of $5,000 Cartier watches, nobody would have said a thing. She knew her employability, and her life, were in ruins.

And then she got an email.

It was from Adrian Loader, co-founder of Australian private equity firm Allegro Funds, which was negotiating to buy ailing transport giant Toll Global Express (now Team Global Express).

TGE was something of a basket case. Loader straight up asked Holgate if she would run it for him. Thanks, but no thanks. She wasn’t going there again.

But Loader – a noted “turnaround” guy running a fund with more than $1 billion under management – persisted. He kept sending her files. She was curious enough to open them and saw that the patient had good bones – revenue of $3.2 billion, two ships, 39 planes, 151 depots, 884 trucks, 3496 trailers and 3496 smaller vehicles. She looked a little deeper.

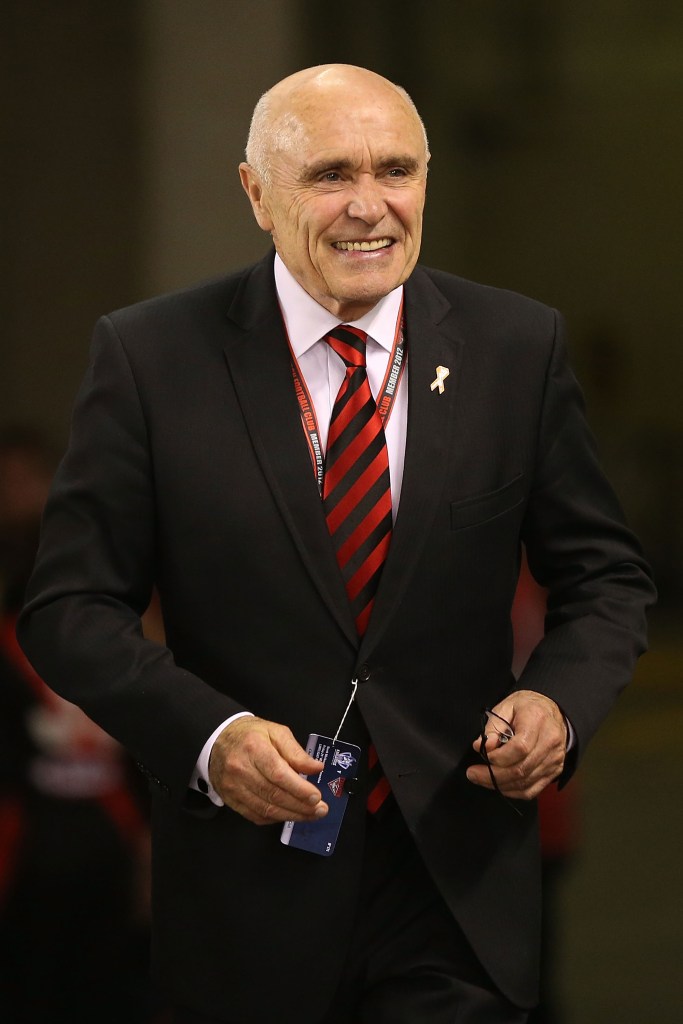

In 1985, Toll Global Express had been an 18-truck, $1.5-million operation when it was taken over in a management buyout by Paul Little (Little served as the managing director of Toll Holdings from 1985 until 2011) and colleagues. After about 120 corporate acquisitions under Little’s aggressive growth strategy, Toll Global Express was bought by Japan Post for $6.5 billion in 2015 – and Little became a member of the Aussie-dollar billionaire club.

Within two years, however, Japan Post had written down its sprawling, dysfunctional asset to $1.6 billion. Toll Global Express chewed up and spat out executives over six years

before Japan Post gave up and sold the Global Express chunk of the business to Loader for just $7.8 million.

As Holgate read the files, she saw that it was losing more than 30% of its workers a year and was similarly haemorrhaging cash. Its “net promoter score” – a measure of customer satisfaction – was minus 52. She didn’t know the score even went that low.

There was something about Loader, however, that she trusted. He wore her down, and she accepted the chief executive job with a generous equity deal.

Loader “got the keys” from Japan Post on 1 September, 2021. On day one, they told managers at every facility around the country to nominate five frontline staff for “listening sessions”. Loader and Holgate wanted to hear from the workers. They had three questions: What do we need to do to make this company great again? What do we need to stop? What do we need to do to grow?

“Adrian and I knew at the end of day two, having done a few (listening sessions), that we’d made the right decision,” says Holgate. “What we saw was an army of people who’d stayed with the organisation throughout all the troubles, through sale processes, through cyber-attacks, through multiple different CEOs, and they had a passion.

“One lady said, ‘We just want hope to be great again, Christine.’”

Christine Holgate

It was a field in which Holgate had form. While most Australians know her as ‘that woman from the Cartier watches scandal’, she more rightly deserves to be known as a bringer of hope to employees and shareholders alike. She was using a playbook – being humble and listening. It had achieved extraordinary results at Australia Post, but even before then, she’d been named Australia’s top CEO by CEO Magazine, for transforming a mid-sized supplements company.

Blackmores

Holgate had come to the vitamin manufacturer Blackmores from Telstra, where she’d been a marketing executive. Within months as CEO in 2008, she identified Asia as the big opportunity, rather than the US, where others were telling her they should expand.

“I used to live in Hong Kong, and I remember getting sick, and my secretary took me to a herbalist to get better,” she recalls. “Nobody questioned whether that was sensible. It happens in their culture.”

Blackmores had a small loss-making presence in Asia, and there were no Aussie brands “kicking it” there, she says. “The first thing I did was I stole the head of Asia from Austrade (Peter Osbourne) because he’d lived in the region for a long time. He spoke several languages, and he understood the regulation and the governance.”

With each new country Blackmores opened in, it made sure to employ locals. “But we looked for people who had an understanding of Australia. Our leader in Hong Kong, for example, had studied in Australia, and that gave us somebody who understood the culture, the language, and the customs but also understood the importance of regulation and controls in Australia. It worked very well.”

The expansion catapulted Blackmores into the ASX200 as the share price rose from around $18 when Holgate joined in 2008 to peak at more than $200 in late 2015. But she has said that her proudest moment was announcing that all employees would get nine weeks’ extra pay that year. Rewarding staff is important to her.

Taking on the Banks

Holgate was headhunted to Australia Post in 2017 with a reported base salary of $1.375 million and the potential to double it with bonuses. It was nevertheless a pay cut from her $2.84 million package at Blackmores. Her predecessor, Ahmed Fahour, pocketing $5.6 million in a year led to criticism by then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull. Fahour left with a $10-million golden handshake.

Two months before Christine Holgate took over Australia Post in 2017, she rang the organisation’s greatest critic, Angela Cramp. Cramp owned two small, licensed post offices south of Sydney and was the leader of a group of disaffected licensed post office owners complaining they were being squeezed out by an uncaring head office.

Tell me what I need to hear,” Holgate told Cramp. “What are your main pain points?

Cramp had a long list, but right up the top was the fact that the post office licensees were losing money every time someone did a bank transaction with them. Bank transactions were rising fast as banks shut branches, leaving post offices as the last institutional contact for hundreds of thousands of small-town Australians.

Cramp spent two hours on the phone with Holgate. Cynical and defensive, Cramp still had no doubt the incoming chief was just like all the rest and would do nothing about it. But Holgate accepted Cramp’s invitation to address the licensees at their annual general meeting the night before she took over as CEO.

“She and her husband Mike came out to Penrith (in western Sydney) and addressed our AGM,” recalls Cramp. “And there were so many tears. It was incredible.”

The way Cramp tells it, Holgate said she’d investigated their claims and agreed with them: “We are losing $50 million a year doing these banking transactions, and I’m not sure why we’re doing that … But I’m wondering how we got into this situation and what we need to do about it.”

She got a standing ovation, but the audience still wondered what she could do.

Delivering

One of the first things Holgate did at Australia Post was to commission research. “What that research showed us was that a community post office was second only to Medicare in the importance communities placed on it,” she says. “More important than the police.” Banking services were one of the things making it so important.

“But those post offices were still counting money by hand,” she says. They needed huge investment. She sent her executive team out to negotiate with the banks: that if they wanted to stay in these communities, they needed to pay for it. Or maybe, it was suggested, Australia Post just might have to create its very own bank.

Three of the big-four banks agreed to each pay a $20-million-a-year ‘community representation fee’, with transaction fees on top of that. “We then rolled it out to about 70 financial institutions,” recalls Holgate. “The smaller the institution, the smaller the community representation fee, but everybody had to pay the same fee for usage.”

It was a lifesaver for the post office owners and was one of several initiatives that

returned Australia Post to profit. Rather than pay the four executives who’d negotiated the deal a six-figure bonus, Holgate famously – and frugally – presented them with Cartier watches.

She revealed the gift to the Senate estimates committee in October 2020. Later that same afternoon, then prime minister Scott Morrison said that Holgate should stand aside pending an investigation, and if she didn’t, “She can go.”

Truck-driving woman

On Holgate’s third day at Toll Global Express, September 3, 2021, she and Loader held a board meeting and started making changes. All the executives in the company who were on incentive schemes would now have 40% of those incentives tied to customer satisfaction ratings.

“The second thing we did,” recalls Holgate, “was to make an immediate commitment to bring home things like credit management from India. That was the number one problem for customers and employees. We had outsourced all of our credit management and customer service. You had to write an email and wait for them to come back, and there were many language issues and delays. It caused a lot of frustration for everybody.

“Just announcing that we were going to bring it home was so motivating to employees because it said: ‘You’ve listened to us.’”

They went on to do 150 listening sessions and surveyed more than 22,000 people connected to the business – staff, customers and suppliers. By the end, they’d hit all the pain points with no anaesthetic.

Holgate and Loader worked at stripping bureaucracy, taking away “lots of silly rules”, such as the one where if somebody quit, the manager in charge had to get a replacement signed off by multiple people above them. “So we said ‘no, if it’s on budget, only your one-up manager needs to sign it off’.” If somebody was going to be promoted internally, a rule forbade them from getting more than a 10% pay rise. “So what happened,” says Holgate, “was that nobody wanted to take the promotions and all your good people left. You’re constantly having to recruit from outside … Fancy not keeping your best people … while that rule change didn’t impact a lot of people, it impacted a lot of people’s motivation.

“Within our first 12 months, we were able to halve labour turnover, and we took the business back to growth in the first seven months. We ended that year with revenue up about 16%.”

Now it was time to refinance the business. Allegro had got into Toll Global Express with a leveraged buyout using non-bank debt. It needed money on better terms.

Andrew Hinchcliff, the Commonwealth Bank’s group executive of institutional banking and markets, recalls Holgate coming in for an hour’s meeting but staying much longer. She impressed him. He could imagine her going out and sitting with truckies and rallying them to the cause.

“My thinking was,” says Hinchcliff, “if she’s that good with me, that influential, that across the detail and that empathetic with respect to her people and her team, then she’s going to be pretty much that influential with everybody else she speaks to, which gives this business a good chance of being successful and it’s worth backing.”

They would go on to sign a $250 million refinancing deal.

There were a lot of hard conversations. The previous business model had favoured volume over margin to the extent that – just as with Australia Post and the banks – they were losing money on some big customers.

“We had to go to those customers and talk to them and share with them our challenges and be very open about that. And that is very tough, but I deeply appreciate the customers who’ve helped us on this journey and have stayed with us.”

It had been reported that previous management had failed to tame the “warlords”, the divisional heads of the company’s still balkanized corporate conquests.

But Holgate rebuilt the leadership team. “I’m proud to say that we now have half of our executive team as women. We’ve had to talk to some employees about whether they were in the right job. You know, sometimes people see themselves in one role, and you might see them in another.

“But my learning is that whichever conversation you have, you treat people with respect. People can handle difficult conversations if they are respectful and you give evidence for why you’re doing things, but if it’s just sheer bullying or disrespectful, expect people to object.”

Earlier this year, Holgate announced a deal with rail freight operator Aurizon worth $1.8 billion over 11 years. It will allow Team Global Express to offer its container customers greener options. And recognising heavy transport’s contribution to greenhouse gasses – 17% in Australia – in December, TGE said it was trialling 60 heavy electric trucks. It will invest $24 million of its own money and receive $20 million in federal funding for the experiment.

Under Holgate, TGE also got out in front of the new Albanese Labor government with providing paid domestic violence leave, plus paying superannuation on parental leave and carers’ leave.

“What we’ve seen is a lot of people come and say, ‘Can I have three months off because I need to go and care for this parent who’s ill?’ And then when they take that time off, they’re not paid their superannuation. So we wanted to make sure that they don’t become disadvantaged for doing something so important for their family.

“And again, ahead of the previous government, we put in place very clear policies for relief. So, when the floods in Lismore happened, we were the first to give $2,000 cash to anybody that had their home damaged. The second thing is we said for anybody who lost electricity, we would give them a voucher for $500 to restock their fridges. We didn’t want them to become disadvantaged at a critical time.”

Transport Workers’ Union national secretary Michael Kaine praised Holgate for her willingness to meet workers and negotiate.

“Over the past two years, Team Global Express workers have succeeded in achieving industry-leading 15% superannuation, CPI-linked pay increases and job security protections,” Kaine says.

“Holgate has certainly endeavoured to show that investing in workers is good for business … When Scott’s Refrigerated Logistics collapsed, Team Global Express was one of the first to open its doors to redundant workers.”

Michael Kaine, Transport Workers Union

For all that, Holgate says that when TGE reports in June, the financial numbers will be good. “We’ve got a significantly improved profitability position. There’s a long way to go.”

Meanwhile, the postal service she left in profit is anticipating major losses this financial year but still found the cash to pay eight executives more than $500,000 each in bonuses – 100 times more than those Cartier timepieces. The inquiry into the Cartier watches affair might have vindicated her, but the new role, leading from the front, has redeemed her.

“I got asked the other day, ‘What is leadership?’ And I answered, ‘It’s a privilege.’ Which is what I think. It’s bringing people together, having a vision for the future and inspiring those people.”

Women’s Summit

Holgate addressed the Forbes Australia Women’s Summit in March and talked about resilience, fashion designer, Carla Zampatti and the simple message behind a gift of a spoon

Christine Holgate held an audience of 1600 pin-drop quiet at the Forbes Australia Women’s Summit in March.

With the quiet voice of a woman wronged, she was not, however, afraid to embrace a bit of comedy. Asked how she’d come to look so strong – dressed in a white suit – at the inquiry into her resignation from Australia Post, she put it all down to famed fashion designer Carla Zampatti.

“I used to meet Carla on a Thursday afternoon,” Holgate says. “Forgive me if I get her accent wrong, but she went, ‘Darling, what are you going to wear?’

“I said ‘Carla, wear? I’m lying on the bathroom floor vomiting most days.’

“And she says, ‘Darling, you have to look fabulous. The whole country will be looking at you.’ It was Carla’s white suit jacket.”

Zampatti died a week before Holgate gave evidence. “But wearing her jacket that day, I felt I had her armour, her soul, her protection,” Holgate says.

She agreed that it had been one of the hardest things she’d done. “Because to go to parliament, and to speak up against the man who told you to go (then prime minister Scott Morrison). And it’s his house, and a lot of people are telling you not to do it.”

She was told she would become unemployable if she decided to admit to having had suicidal thoughts.

“But if I didn’t do it, I would never have been able to live with myself because if you don’t speak out, you tolerate it. How would I ever have deserved the right to lead people again and to ask those people to respect each other if I was prepared to be abused and silenced?

“I was still quite ill when I went to parliament, but I had to find that strength to speak out and … I knew it was the only way we could get things to change.”

She said that resilience was a feature that employers often overlooked when hiring. Three out of five women in the workplace suffer bullying or harassment in their life.

“When something happens to you and somebody in one minute can destroy your whole life, you go through a whole set of experiences… It was the Saturday that followed that I was depicted as a prostitute in the Saturday morning paper. That wouldn’t have happened to a man. Yet it was deemed okay. I was told I was not allowed to speak.”

It took a long while to recalibrate. “But one day I just woke up and – excuse me for swearing – I just thought, ‘f**k you, bastards!’ You feel incredibly alone, but once you get to that stage, you can lift your head, and use it for positive change.”

Holgate told the story of how as a teenager, with a shaved head and a nose ring, she’d had an argument with her father and found herself homeless in London at a train station.

“I don’t think at that moment, sitting on the floor of Euston station, I had any ambition to be a CEO. I had the ambition to have a roof over my head – that girl never leaves you.”

She said it was important to frame adversity correctly. “Bad things are going to happen. You can’t change that, but don’t let them define you.”

Holgate said she was struck by the empathy of others when she told her story. The founder of Oz Harvest, Ronni Kahn, gave her a spoon as a present.

“She sent it to me on a particularly bad day. And she talked about the power of sharing. The idea of sharing food, but my advice is that on a bad day, share your troubles because if you’ve got a problem, somebody else has.

“A simple act of kindness, that’s what that spoon was. I’ve carried it every day since, and

if we can all do just one simple act of kindness, we’ll get through this, and we’ll all be so much better.”

Forbes Australia Issue Four is out now. Tap here to secure your copy and membership.