Amanda Healy is an indigenous woman who employs 850 people at her engineering business. And she’s bent on straightening out what’s crooked in the land of opportunity.

Amanda Healy was working up near the Arctic Circle, doing human resources for BHP as they built Canada’s first diamond mine when she faced a problem no male employee ever confronted.

“I fell pregnant to a local guy. It was never going to go anywhere, so I decided to come home and have my child here,” recalls Healy, now CEO of Perth-based Warrikal Engineering, of that time in 1998.

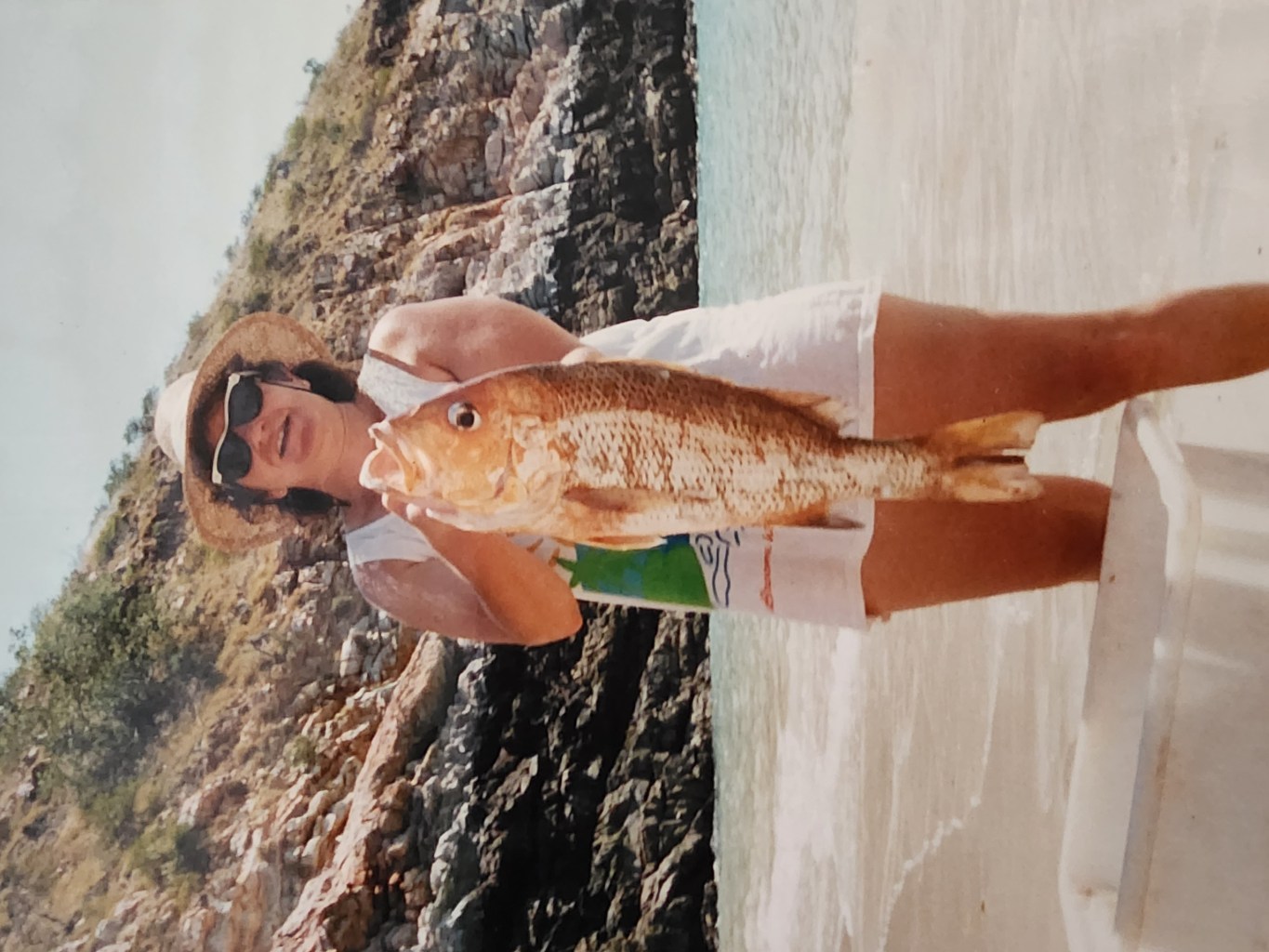

With a new baby, she did a year on contract for Rio Tinto at the Argyle Diamond Mine in the Kimberley and three years for Western Mining. “I found it so hard to be a single mum with a young child in an industry that expected its pound of flesh. We often worked from six or seven in the morning till six or seven at night.”

Perth had a daycare shortage. Her father was dying of cancer, so her mother was occupied. She decided, “in a moment of madness”, that the only way out was to take redundancy and start her own business. Being in HR, she knew there was a crisis in the construction industry, with workers jumping ship as projects neared completion in a bid for job security. “It was constantly in the paper about these independent operators who made multi-millions. ‘If they can do it, why can’t I?’”

She teamed up with a boilermaker, Carey Gardner, and together they put together skilled teams to finish any job, but ended up refocusing on mining jobs and shifted north to Port Hedland. The resources boom was blasting off, and Fortescue Metals had just entered the iron-ore game as a third player. “There was a lot of clean-ups going on around the port, so we were able to pick up a massive amount of work doing whatever: shutdowns, turnarounds, project work, jobbing work.”

There was a growing movement to encourage procurement from indigenous businesses, and so, in 2010, Healy registered her company, which had been renamed Maxx Engineering, as an indigenous business.

Don’t ask, don’t tell

Her father, Bill Healy, was from the Wonnarua people of the NSW Hunter Valley. “Dad was always very proud of his Aboriginal heritage, but he avoided telling people about his history. It was illegal for him to work in many occupations in NSW as an Aboriginal man.”

Healy’s mother, Edith, was white, and she had a relative who was a surveyor in Queensland, where employment was less restricted. He took Bill under his wing and trained him in surveying. The Healy family moved to Western Australia when Amanda was little.

“Dad came here looking for work. People didn’t ask a lot of questions in the mining industry. If your skin was slightly darker or your culture was slightly different, people didn’t care. They just needed bodies.”

Amanda Healy

Bill Healy went on to enjoy a long career surveying West Australian mines, roads and railways while raising seven kids. Amanda was the youngest. “I was pretty independent from a fairly young age,” she recalls. “People never told me I couldn’t do anything, except occasionally, my brothers and sisters would give me a smack around the ear. ‘That’s mine!’”

It seemed natural for young Amanda to gravitate towards mining, and she fell into human resources, including a 14-year stint on tough assignments for BHP. Mark Jackaman was a young accountant at the company’s manganese mine on Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

“Amanda was a trailblazer,” Jackaman, now COO of Cancer Council Australia, recalls. “A young professional woman on a remote Aboriginal mine site, a very blokey mine site, that was heavily unionised. She was in there running HR – a tough gig at any time – but to be a young, professional, single woman doing that was a little bit ahead of her time.

“But as tough as Amanda was in the workplace – and she was pretty tough because she had to be – she was an extremely social person outside of work, and she loved mixing with people.”

Mark Jackaman

“Not just the employees. She did a lot of work with the traditional owners on things like building houses for them, open offers of employment and training for anyone that wanted them.”

From Mining to Fashion

After registering as an indigenous business, Healy got deeper into that world. “I found that there was absolutely nothing in the market representing authentic indigenous engagement in Aboriginal products and with Aboriginal people. Everything was made overseas ‘in-the-style-of’ – boomerangs made and painted in Indonesia and sold in our market as authentic Aboriginal products – which I found unacceptable.” She complained about it for a “couple of years” but got no traction. “I thought, ‘Bugger this! I’m gonna do it myself. I don’t know why there isn’t outrage about it.’”

In 2014, Healy invested $250,000 in Kirrikin. Dubbed the “Gucci of indigenous art”, Kirrikin prints contemporary indigenous art onto fabric for high-end fashion. Healy started it as a for-profit, but working with many socially disadvantaged artists, she morphed it into a social enterprise. “The funds from that go back to the Aboriginal artists, to supporting Aboriginal single mums. I don’t take any money out of that business. But we have established a foundation to help develop other small Aboriginal businesses.

“One of the big issues for our people is that we were excluded from economic participation for so many years that we don’t have generational wealth. I couldn’t rely on my parents to provide me with a guarantee for a home loan, for example. Though I have a different personal story, my friends wouldn’t have enough equity in their house to guarantee the setup of a business. You need half a million dollars, at least.”

Healy had bought out her engineering business partner in 2009 and built Maxx Engineering to a turnover of $15 million with 30 staff. In 2015, she sold out to the German conglomerate ThyssenKrupp for $4.5 million.

She returned to university (having graduated in anthropology and history in the late 90s) to do an MBA. She teamed up with Roy Messer, who’d been at Linkforce Engineering and David Flett, who had a workshop at Henderson, south of Perth. They were white, but Healy owned 51%, so they registered the new business, Warrikal, as indigenous.

“In 2017, we started knocking on doors around Perth to see whether there’d be an interest in engaging with us, which I knew there was because it’s hard to find good mechanical operators, and there wasn’t a single Aboriginal mechanical operator in that space.”

Amanda Healy

By the end of the year, they had about five office staff and 20 temporary workers. “We did $300,000 total revenue, which probably cost us about $600,000. But we know this industry. We were confident we would get there. It was just how much we could do and how quickly we could do it.”

The business had two things going for it. Indigenous businesses get a favourable weighting in tendering, and iron ore and the hard rock and silica that surround it, and the salt used to wash it, are all highly destructive of mechanical equipment. Everything needs regular repair and replacement. “We replace walkways; we replace crushers and conveyors and feeders and anything to do with steel – all the plant that you don’t drive around: ship loading, stacker reclaimers, port equipment, and anything in between. Generally, you would imagine that every piece of equipment in those processing plants would be replaced at least annually, sometimes more often. It’s great for business, and it’s not very sexy, and nobody cares about it, but it can be very profitable – if it’s done very well.”

Warrikal has grown to 850 workers with a turnover “in the realm of $100 million”. It has a target of a 20% indigenous workforce, but as growth accelerated, it struggled to find enough indigenous workers, and is now sitting at 15% indigenous, says Healy.

They signed a $350 million five-year maintenance deal with Fortescue Metals in 2021. And a similar deal with BHP.

And they’ve got no intention of stopping. “We’ve got big dreams about our future. Whether that’s a float, we don’t know. We’re six years old, and we’ve just grown to a point where we have to build a huge structure to continue that growth. We see ourselves stabilising and building over the next few years.”

Former model Shannon McGuire got to observe Healy last year when they went to Europe on a trade mission with various indigenous fashion industry players. “She’s probably one of the best human beings I’ve met,” says McGuire. “She’s always got time to sit and speak with others, and to mentor and help people, so as much as she’s succeeding, she’s holding someone else’s hand along the way.”

Last year, Healy founded the Kirrikin Foundation, to commercialise indigenous – mostly creative – businesses and McGuire came on as CEO in May. “In West Australia, everyone knows Amanda, and Amanda knows everyone,” says McGuire. “She can walk into a room, and even her competitors want to work with her. I call her ‘Mum Manda’. There’s a few of us who call her that now.”

Healy is also one of the Blak Angels indigenous investors – a group brought together by the Forrest family’s Minderoo Foundation – to seed First Nations start-ups. “It’s so great to see these kids coming through – their enthusiasm, how savvy they are, how well-educated and how interested they are in making a difference, and how interested they are in participating in the broader economic community,” says Healy.

While she remains CEO of Warrikal, its growth has meant she can delegate some of the more mundane problem-solving jobs to spend more time mentoring the young and schmoozing the old. “I love doing the relationship stuff. I get to watch football matches and have a glass of wine with the big bosses. So that’s a nicer side.”

Forbes Australia suggests that she’s living a dream she could barely have imagined when returning from Canada, single and pregnant 25 years ago.

“Exactly! Next minute, I’ll be driving a bloody Mercedes Benz, and nobody in the community will talk to me anymore!”