Francis Wedin built Vulcan Energy into an $800 million green lithium powerhouse – and got the feuding Rinehart-Hancocks on his share registry.

Francis Wedin was a 27-year-old fly-in-fly-out geologist at a West Australian gold mine in 2013 when he read an article about Tesla that would lead him to solving one of the more intractable problems of electrification and founding Vulcan Energy Resources, a company which at it’s peak has been worth $1.8 billion.

A bit of an environmentalist – “Dad’s Swedish roots have something to do with that” – Wedin had been thinking about energy transition. When he saw what the then-upstart EV maker was doing with its batteries, he did a few quick calculations.

Many crucial minerals required for electrification – like copper and nickel – were already enormous markets. But lithium production was tiny.

The “fly-out” part of FIFO life meant he had time on his hands. He started researching after getting a PhD out of the way – and having done a modern-era-first by rowing from Turkey to Cyprus, and despite being deep in training for ironman triathlons.

The tiny lithium market was predicted to grow from 100,000 tonnes per annum to 5 million tonnes in the space of a decade or two.

At 28, he co-founded Asgard Metals to explore for lithium and, at 29, found himself as an executive director of an ASX-listed company. Asgard discovered and developed a hard-rock lithium deposit in the Pilbara.

Along the way, Wedin realised lithium’s dirty, not-so-secret problem: that processing it consumed large amounts of coal-fired energy in China, negating much of the benefit of electrification. There had to be a better way.

In 2018, he got out a whiteboard and wrote the endpoint: “zero carbon lithium”. He worked backwards from there, reading research papers until he thought he’d found the solution.

The company he founded in 2018, Vulcan Energy, turned on its test plant in Germany last April and, in October, began producing Europe’s first domestic lithium, plus four megawatts of power an hour, all with zero carbon emissions.

But the Cyprus-born Australian has much grander ambitions for Vulcan, a $1.1-billion ASX company that has variously been a stockmarket darling and dud, and which has sparked something of a competition between two feuding arms of Australia’s richest family, the Hancock/Rineharts.

Hard rock

Wedin’s research took him to lithium brines – subterranean salty water from which the mineral was already being commercially extracted. The most widely used extraction method – “adsorption” – was more eco-friendly than the hard-rock methods but still required a lot of heat to drive the process.

“I try to be very Zen and zone out of the whole thing, whether it’s going up or down. But my wife tells me there’s a direct correlation between my mood and the share price.”

Vulcan founder Francis Wedin

Wedin’s breakthrough was the realisation that if you could find hot brines in the ground, you could use the embedded heat to take out the lithium – and maybe even use excess heat energy for geothermal power. Not only would it be carbon neutral, it might even be carbon negative.

In 2014, when he was trying to launch Asgard Metals and sell the notion of hard-rock lithium to investors, it hadn’t gone well. “I was laughed out of the room because brines were seen as a very low-cost way of producing lithium,” recalls Wedin. “Everybody said, the big guys who are producing lithium from brines; they’re just going to increase production, stop the market, you guys are going to be nowhere.”

But the lithium price surged. Asgard and other West Australian hard-rock lithium players did well, and Wedin sold Asgard to Pilbara Minerals.

Freed up to pursue his zero-carbon lithium dream, Wedin employed a PhD student to look for places around the world where the right conditions existed. While Australia does have potentially suitable sites, Germany’s Upper Rhine Valley was more compelling because it already had a geothermal energy industry based on hot underground waters.

“It was well known in German geothermal circles that there was lithium in the brine,” Wedin says. “But the opportunity was that the geothermal industry in Germany had no lithium expertise.” He founded Vulcan Energy to fill that gap. It was listed on the ASX in mid-2018.

“Being quite pushy and entrepreneurial, I wanted to run it myself, at least initially,” says Wedin. He bought a German geothermal energy consultancy that had already built numerous geothermal projects in 2019, and its owner, Dr Horst Kreuter, became a co-founder in 2019.

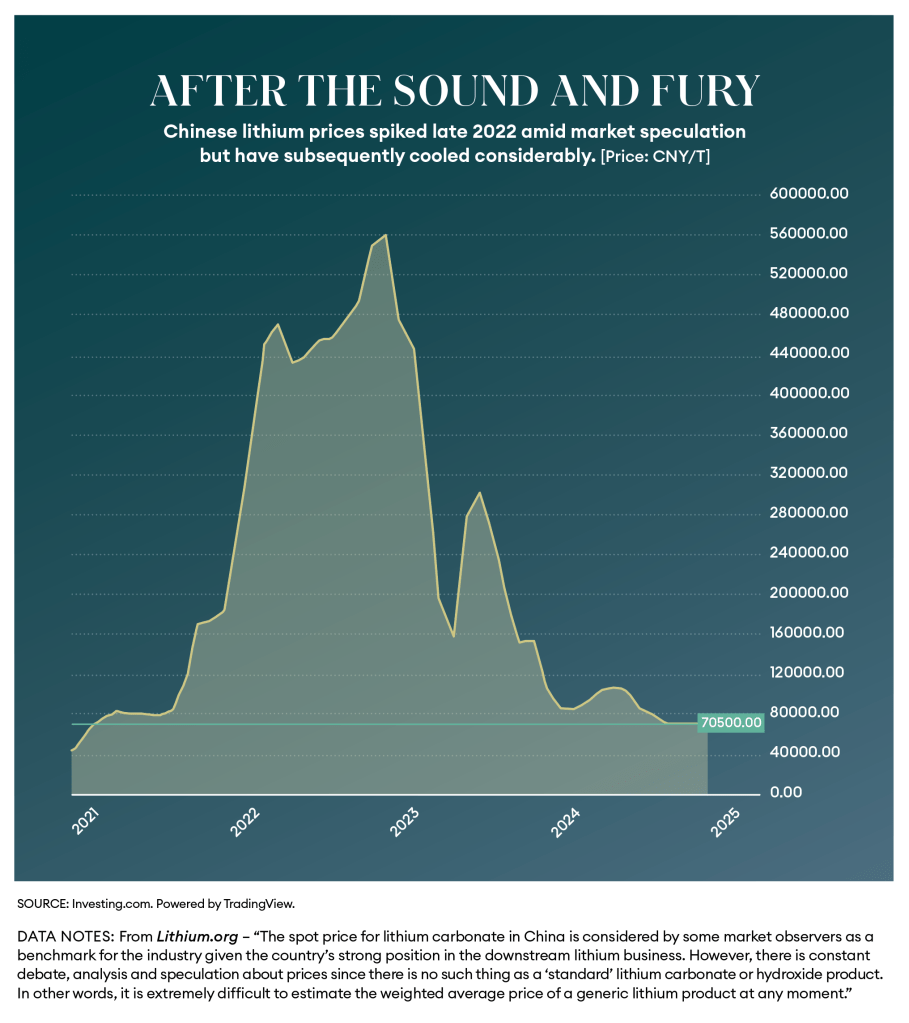

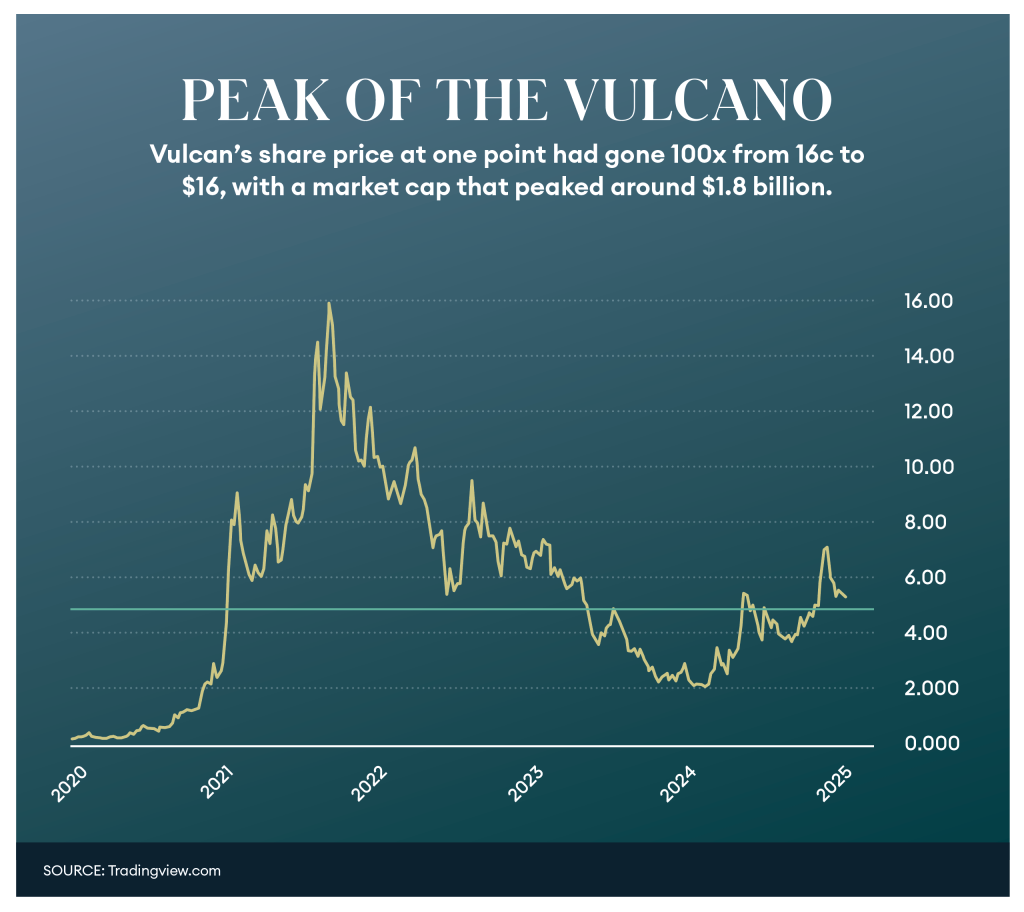

The timing was good. The lithium spot price had been steady for years; around $8 a kilogram. It started rising in 2020 and was over $80 by late 2022. Within 20 months, Vulcan’s share price had gone 100x – from 16c to $16, with a market cap that peaked at around $1.8 billion.

One of the early investors to come on board was Hancock/Rinehart family scion John Hancock [see below]. His mother, Gina Rinehart, also jumped to near the top of the share register.

Vulcan rode this wave. It raised $120 million at $6.50 in February 2021 and $200 million at $13.50 in September 2021, for a total of $320 million.

“That meant we could accelerate the project,” says Wedin. “We brought in some fantastic people.” Vulcan grew to 350 staff and bought a couple of engineering businesses and some drilling rigs, which were in short supply.

“We spent about 100 million bucks on the [adsorption] technology as well,” Wedin says. “It’s been used commercially since 1996, but the field of companies that have this technology is very small. We were lucky to pick up some key experts and develop our own version of it in-house.”

“Now we’ve got the resource, the people, the technology and advanced it to a stage where it’s shovel-ready. It’s just awaiting that final approval on the financing side and we can start building this thing.”

Wedin, as a geologist, recognised his corporate limitations and, in 2022, brought in fellow West Australian Cris Moreno to take over the running of the company. Moreno became CEO in 2023. Wedin now styles himself as an “investor-facing” executive.

Vulcan Energy has locked in deals with most of Europe’s major car manufacturers – eager to secure lithium supply chains and lower carbon footprints.

Stellantis – the owner of Alfa Romeo, Chrysler, Citroën, Fiat, Lancia, Opel and Peugeot – is Vulcan’s third largest shareholder behind Wedin [8.3%] and Rinehart [7.5%].

The machine

The lithium price plummeted through 2023 and has now stabilised around US$11/kg, a price that’s seen several Australian hard-rock players stop production.

But Wedin says Vulcan can be profitable at that price. “Our cash cost of production is about $4,000 a tonne [$4/kg]. We produce at the bottom of the lowest quartile of cost. So brine’s already the lowest quartile, but because ours is a heated brine and our competitors are using gas to heat up their brine, not only is it a very low-carbon process, but it’s a very low-cost process.”

Vulcan opened a prototype plant in the German town of Landau in November 2023, producing its first lithium in April 2024, and has a green light to build the full-scale version next door. Aside from producing 24,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide a year – enough to make 500,000 EV batteries – the full-scale plant is expected to produce enough electricity to power 10,000 homes and about 560 gigawatt hours of heat per annum, which will directly heat about 90,000 homes.

Vulcan’s share price had been in decline for two and a half years since its peak above $16 in 2021. It bottomed at $1.95 in February 2023 and has been trending up since then.

Wedin praises his major investors for toughing it out, singling out Hancock Prospecting, which, at the bottom of the market, had lost millions on Vulcan. “They’ve been amazing, supporting us on every raise, and they’ve increased their ownership this year to 7.5%. In 2022, Stellantis became our largest off-taker, and they became a substantial shareholder as well.”

Hancock Prospecting declined to comment on its Vulcan investments, but scion John Hancock said it was his confidence in Wedin that kept him on board when the share price plummeted.

“By that stage I was a confirmed Vulcaneer,” Hancock says in an email. “I’d met Francis and was very impressed with him. In fact, he came on my yacht for an afternoon (which I had Vulcan to thank for) on the way back from Germany and didn’t stay any longer as he was so focused on progressing the project.”

Wedin has consistently set targets that many thought were unattainable, Hancock says. “And he has been knocking them off one by one. He is a machine. That gave me a lot of confidence to hold the position, although I did sell a small amount, around $15, to fund the boat I mentioned above and small amounts along the way to fund the lifestyle I was leading. My plan was to hold for $20, and I still hold over 4 million shares. $20 will come one day.”

Zen and the art of carbon-cycle management

Wedin points out that Vulcan was the best-performing lithium stock in 2024, up more than 200%. The company needs to raise 1.4 billion to build the full-scale plant. He says the 40% equity portion of that has been secured – thanks in no small part to Rinehart and to the German federal government, which chipped in €100 million – and the 60% debt portion is close.

Wedin expects to have the full €1.4 billion finalised by March and to have shovels in the ground before then.

“Every time we build another lithium project, we’re building more renewable energy generation.”

Chris Wedin

Vulcan’s fourth largest shareholder is CIMIC, formerly Leighton Holdings, now owned by the German engineering and construction giant Hochtief, which is likely to be involved in building the project, says Wedin.

“That’s how we want to build Vulcan, to have these long-term strategically aligned investors.

“So I think with the phase-one financing that we’re getting to the pointy end of now, we’ve got backing from the European Investment Bank, export credit agencies from four different countries [Export Finance Australia committed to loaning $200 million in December], a lot of European banks in there, [European Investment Bank has approved a funding envelope of €500 million] but we’ve also got strategic investors who will be coming into the project.

Wedin sees Vulcan continuing to add new plants across the Rhine Valley.

“It’s a very big resource. It’s very homogenous chemistry. We can just grow as the market grows. Every time we build another lithium project, we’re building more renewable energy generation.”

Wedin stresses that the long-term goals are paramount in his thinking and the stock market is but a distraction. But it’s a distracting distraction.

He owns about 16.5 million shares, worth about $100 million at the time of going to press.

“I’ll be honest with you. I try to be very Zen and zone out of the whole thing, whether it’s going up or down. But my wife tells me there’s a direct correlation between my mood and the share price.”

Hancock in early

John Hancock, son of Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart, was living in the Canadian ski resort town of Whistler in late 2019 when he got talking to an old Perth friend, Gavin Rezos, who’d just become Vulcan Energy’s chair.

“I was immediately intrigued as I loved the ‘circular’ nature of the project – using its own heat as a power source, extracting the lithium, and returning the water to the earth for the cycle to continue,” recalls Hancock.

“The more I researched, the better the project became in my eyes.” He started buying shares.

“When the EIT [European Institute of Innovation and Technology] InnoEnergy fund took a tranche at 51c (in July 2020), that gave me confidence to go hard on Vulcan.”

He wasn’t the only one. “When the price started taking off, I wasn’t quite ready. I had really wanted to get above the 5%, and I hadn’t gone fast enough – the higher the price went, the more expensive that was going to be. I put all I could into Vulcan. Anyway, I managed to get there [5%].”

By the time he announced himself as a substantial shareholder in January 2021, the shares had cost him an average of almost $1. His mother’s Hancock Prospecting Ltd started buying soon after and went over 5% on February 11, 2021 by which time the share price had gone up over $9.

Hancock felt vindicated. He and his sister Bianca Rinehart had been engaged in a lengthy court battle with Rinehart over control of a trust left to them by their grandfather, mining magnate Lang Hancock.

“That validation of my investment methodology, my network and personal research with no budget or staff assisting, resulting in my early investment in Vulcan to be followed by the HPPL [Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd] investment committee, was interesting, to say the least, given the presence of the litigation between us.”

Hancock and his sister Bianca Rinehart are suing their mother, HPPL owner Gina Rinehart, over .]

The money meant a lot to him. It allowed him to escape the UK’s COVID-19 lockdowns in Dubai and then the Maldives. “There may have been a shopping trip or two for my wife and daughters in Dubai; at one stage, Vulcan was going up $1 a day – I held around 5 million shares, so it was a nice thing to wake up seeing what had happened on the ASX overnight. We then negotiated some great rates at amazing Maldives villas, which were suffering from low occupancy due to travel restrictions. For us, it was a very special few years; my three daughters were home-schooling with us, and experiencing some amazing places without tourist crowds.

“If it weren’t for the success of Vulcan, we wouldn’t have been able to do that. We were

very lucky.”

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.