The world is entering a new era of harnessing brain information with technology able to translate the brain’s electrical codes and signals into computer commands.

Imagine having a thought that is automatically sent to a computer, that then carries out a task on your behalf, such as sending a WhatsApp message or paying a bill online, all while never lifting a finger. It sounds like the stuff of a science fiction film – but thanks to a booming brain interface computer market, this technology is very much a new reality.

For 62-year-old logistics worker and ALS sufferer, Philip O’Keefe, brain technology called Stentrode allowed him to Tweet his thoughts for the first time in a very long time. “Hello, world! Short tweet. Monumental progress” his tweet read.

The world is entering a new era of harnessing brain information with technology able to translate the brain’s electrical codes and signals into computer commands. For business – it’s a potential new multi-billion industry – and for people with degenerative diseases, severe disabilities and paralysis, it is life-changing.

For O’Keefe, the innovation has allowed him to regain some of his independence, giving him the ability to sort his emails, surf the web and do online banking, doing “most things you can do with your hands”.

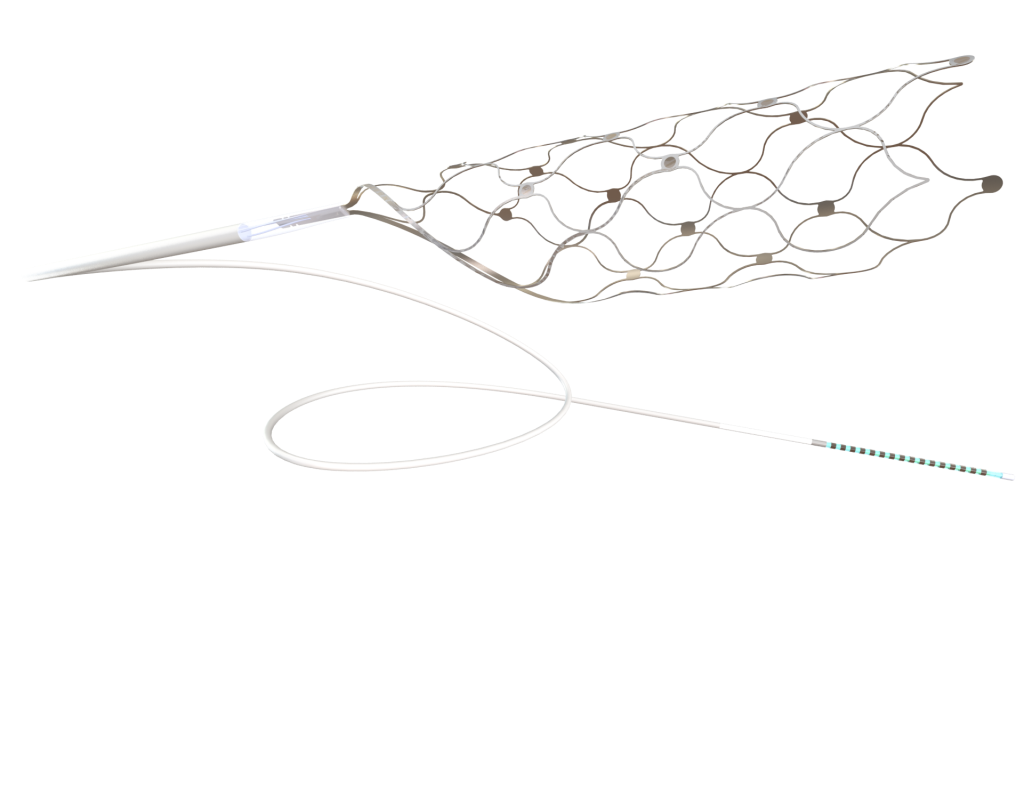

The Australian start-up medical tech business behind the Stentrode device O’Keefe uses is Synchron. Stentrode is smaller than a paperclip that is inserted into a blood vessel next to the brain’s motor cortex via the jugular vein, allows paralyzed people to control a computer with their thoughts. It has already attracted various government grants and raised around $100 million in capital, attracting investors such as Khosla Ventures and Max Hodak, the former president of Elon Musk’s Neuralink.

Melbourne-based Professor and Synchron co-founder, Nick Opie, says innovations such as these are creating a potential multi-billion-dollar, life changing industry that has previously not existed. Professor Opie – Head of Vascular Bionics Laboratory at Melbourne University – says while the technology behind Stentrode was developed by professors, it was always meant to be commercialised and to be used to help people.

“We really wanted to make it [the technology] into a product that could get to the people who needed it. I’m not sure how many researchers and academics you have spoken to who have made amazing stuff, but often it doesn’t ever get out,” Professor Opie told Forbes Australia.

While some of its competitors are big names – Neuralink, Apple and Google – Synchon has one huge advantage – it has one substantial advantage: FDA approval to run a clinical trial. It has already trialled use of Stentrode in four patients in Australia, who have been able to send WhatsApp messages, do online banking and make online purchases. It recently inserted the device on its first US patient at Mt Sinai Hospital, putting it ahead of competitors. So far users have reported no serious side effects from the implant, which is designed for automated, long-term use.

The results of the trials so far have been surprising. Not only has the technology impacted patients, but their families too, Professor Opie says.

“The wife of one man with MND told us she really wanted him to be able to use his phone, because she always needed to be with him because he couldn’t communicate. She wanted to be able to go out in the garden or down the street and have him be able to contact her on the phone if he needed. I think her quality of life improved as a result too. It’s not just the person – it’s their family as well, having the ability to know their loved ones are safe.”

“A couple of people have just wanted to be able to control their TVs and we could do that for them too,” Professor Opie said.

Professor Opie says the company he co-founded 10 years ago, caught the attention of the brain-computer interface (BCI) sector because of the non-invasive nature of its devise, which can be inserted into the brain without cutting through a person’s skull or damaging their tissue.

“Our major difference is the technology. It’s one where you don’t have to use a saw or a drill to burrow through the skull to get to the brain – we don’t do that. Our procedure is a lot safer, going through blood vessels,” he says. “That’s one of the things that regulatory bodies like the FDA look for, in terms of safety, which has allowed us to progress faster.”

While Stentrode is making inroads in America, Musk’s latest announcement about Neuralink was postponed by a month earlier this year, with no explanation other than a Tweet from Musk himself, promising a “show and tell” about the company at the end of November. The news comes more than a year after the company posted footage of a monkey, assisted by Neuralink’s chips, playing ping pong on a computer using only its thoughts. So far, Neuralink is yet to proceed with trials in humans.

In the coming months, Synchron aims to shrink the size of its devices while increasing their computing power. If it’s successful, the company would be able to place numerous Stentrodes in each patient in different parts of the brain, allowing people with severe disabilities perform more functions that would help them go about their day-to-day lives, Professor Opie says. It hopes the device could be accessible to the public in around five years.

For trial participant O’Keefe, the innovation came just in time: “This gave me a reason to keep on living. A few years ago, I would have been gone ‘oh what’s the point?’ but now I’m involved with this and it’s just been the most exciting two years of my life.”

There have been reports that Neuralink owner, Elon Musk, is interested in doing a deal with Synchron given its FDA status and progress in human trials. Musk is due to give an update about Neuralink at the end of this month.