Data journalist Juliette O’Brien digs into Australia’s mineral resources to find the opportunities that await the country in a greener world.

This story featured in Issue 12 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

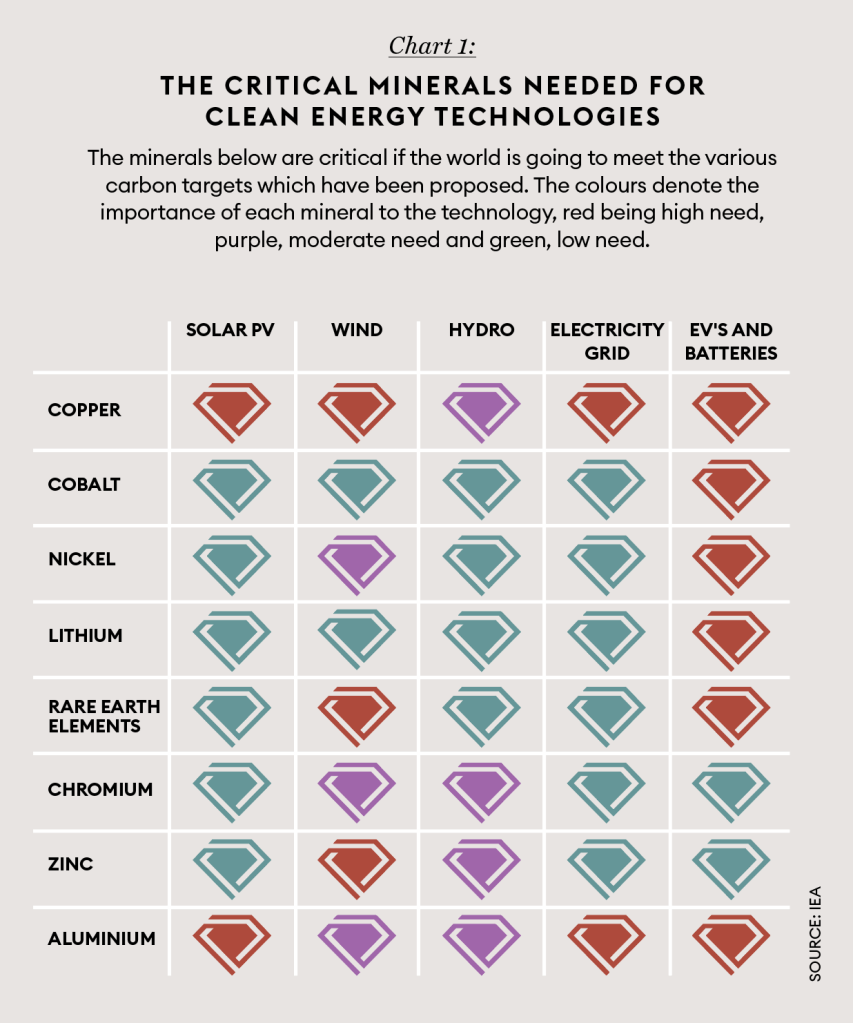

The world’s transition to clean energy relies on critical minerals. (Chart 1).

Wind turbines, which power eight per cent of the world’s electricity, need copper, zinc and Rare Earth Elements (REEs).

Solar panels, which provide six per cent of global power and are doubling in capacity every three years, use millions of tonnes of aluminium.

Batteries running electric vehicles and storing renewable energy are made from several minerals, including lithium, nickel and cobalt.

The electricity grid is expanding, requiring vast amounts of copper and aluminium.

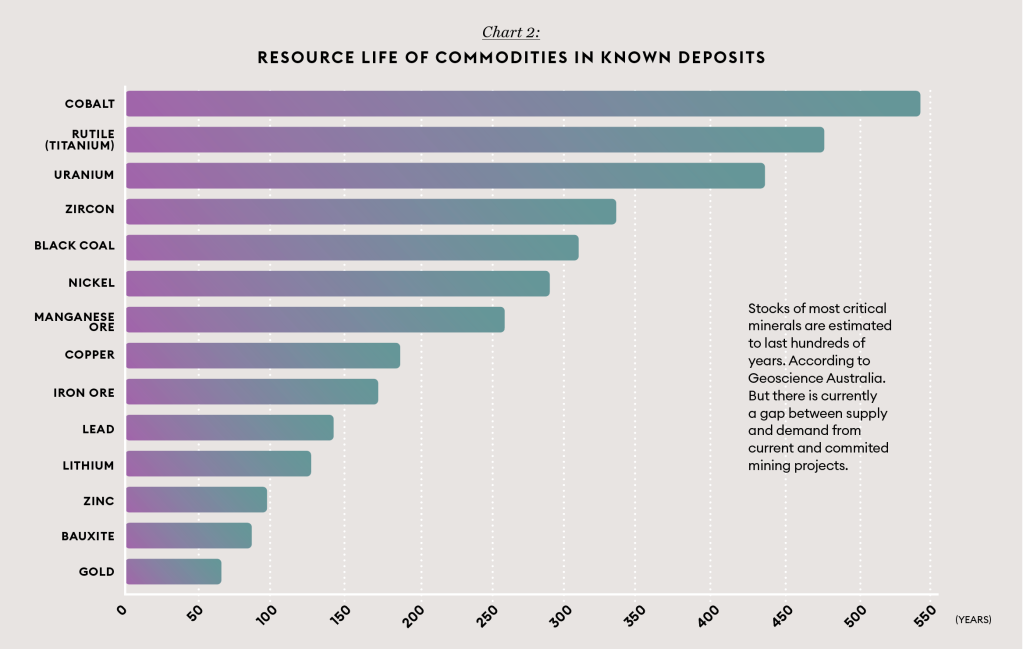

There is no shortage of reserves. Global stocks of most critical minerals are estimated to last hundreds of years.

According to Geoscience Australia, the resource life* of all known deposits of cobalt, rutile and lithium are 530, 465 and 120 years, respectively. (Chart 2). But the scale and pace of the world’s clean energy ambitions mean a gap between demand and supply from current and committed mining projects is looming.

“Today’s investment plans are geared to a world of gradual change,” says the International Energy Agency (IEA). “Given long lead times for new projects, an accelerated energy transition could quickly see demand running ahead of supply.”

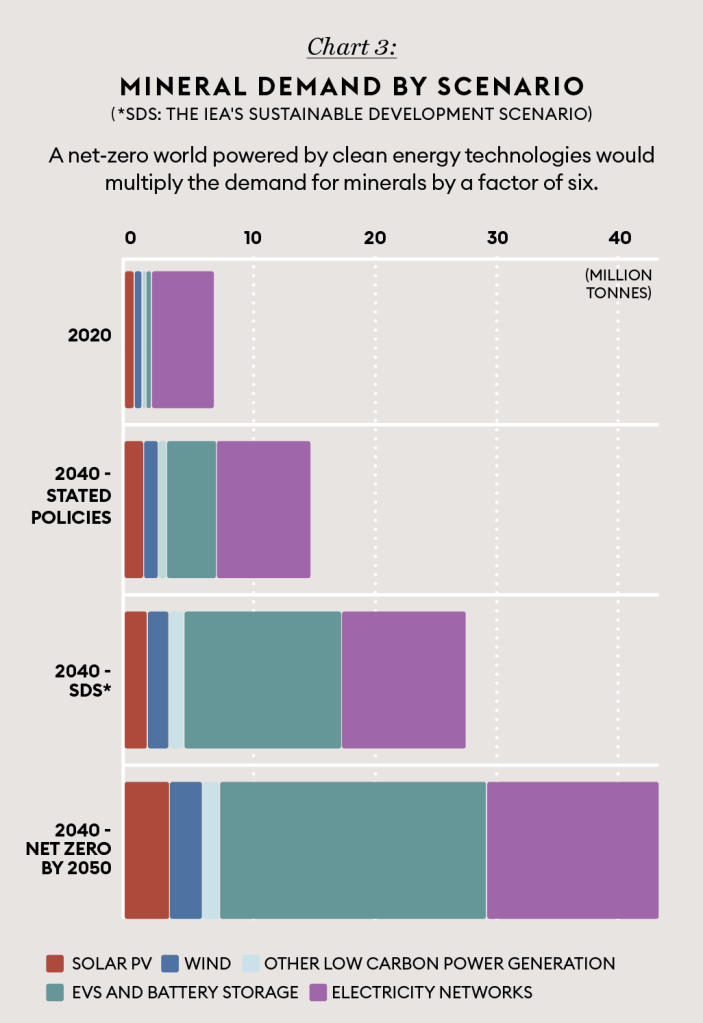

Each megawatt of power generation capacity already needs over 50% more minerals compared with 2010. A net-zero world powered by clean energy technologies would multiply the demand for minerals by a factor of six. (Chart 3).

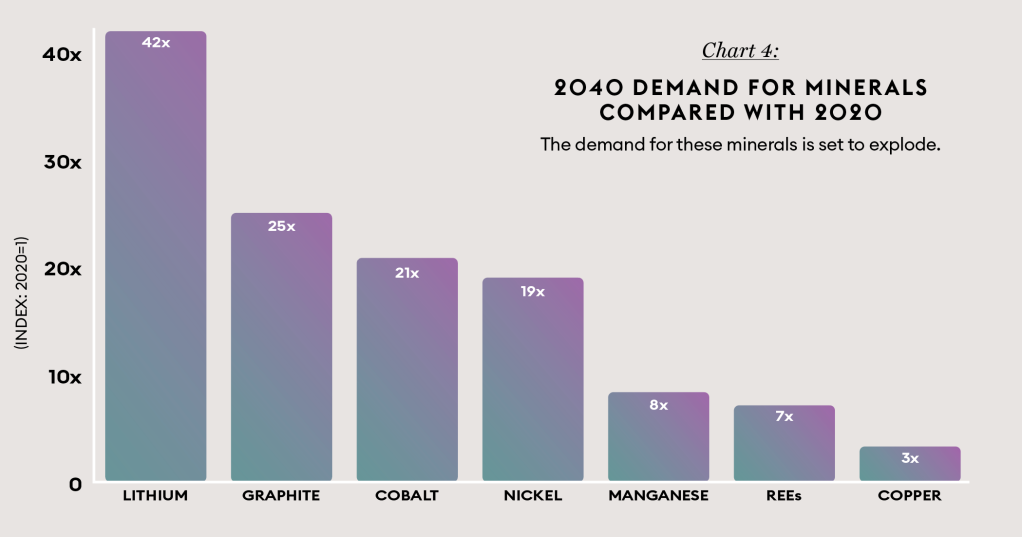

Even the less ambitious Sustainable Development Scenario (where global emissions align with the goals of the Paris Agreement) could see the need for lithium explode by over 40 times, followed by graphite, cobalt and nickel, which would see demand grow by 20x to 25x. (Chart 4).

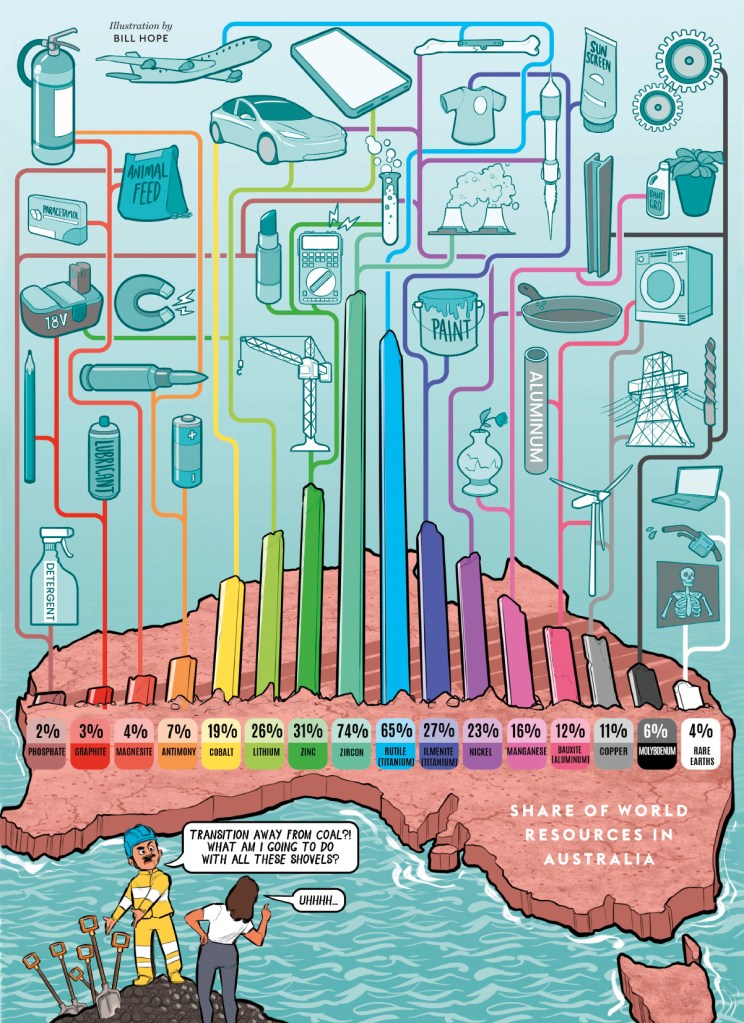

The good news for Australia is that many of these minerals are in the country’s dirt. (Chart 5 – Illustration).

According to Geoscience Australia, the country has the world’s largest Economic Demonstrated Resources (EDR) of nickel, rutile, zircon and zinc.

Nickel is used in vehicle manufacturing, electronic engineering and lithium-ion batteries.

Rutile is the central source of titanium, which is used to build aircraft, vehicles and industrial equipment.

Zircon makes superconducting magnets, and zinc feeds transport industries and electrical equipment.

As for production, Australia is the top global producer of lithium, rutile and bauxite (aluminium); the second largest producer of zircon; the third largest of manganese, rare earths and zinc; the fourth largest of cobalt; and the fifth largest of nickel and tantalum.

However, to fully capitalise on the minerals rush, the nation must look beyond extraction and break into the club of countries that dominate downstream processing and refining.

The top-producing countries in this area are heavily concentrated, with China dwarfing the rest. (Charts 6a and 6b).

The Albanese government has launched a $7 billion tax incentive to encourage Australian companies to “value-add” throughout the supply chain by processing and refining critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earths.

It is a strategic step that aims to squeeze maximum value from Australia’s critical minerals.

An abundance of natural resources and booming demand might be seen as more luck for the lucky country.

But the harder Australia works, the luckier it will get.

Data notes

*Resource life refers to all deposits, including Economic Demonstrated Resources, Subeconomic Demonstrated Resources and Inferred Resources. Figures rounded to the nearest five years. Year calculations made by Geoscience Australia using the total amount of a commodity available divided by the current rate of production.

**World rankings determined by Geoscience Australia by comparing Australia’s EDR and production to economic resources and production reported for other countries. Undocumented resources and production are not used in the analysis.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.