Peter Barrett dropped out of Sydney uni to head to Silicon Valley in 1986. He gave Elon Musk his first job in the Valley, worked with Bill Gates, and started a venture fund, Playground Global, that has had 20% of its portfolio hit billion-dollar valuations. He also started a school in his backyard. He has been back in Australia a lot recently, looking at start-ups, spruiking one of his early investments – PsiQuantum – and trying to dip into Australia’s vast superannuation pool.

Why are Playground Global and Peter Barrett so good at picking winners?

Our superpower is underwriting technical risk. We have 38 people on the team and most of them are scientists and engineers. We know what we’re looking for and we know when a technology is ready to commercialise. We don’t guess. We looked at 30 green steel companies, and those technical assessments showed that Element Zero, an Australian company, was going to be a monster. We know their technology works. We know the [PsiQuantum] quantum computer will work. Not everybody has a bunch of smart scientists and engineers on staff that can underwrite technical risk and work with the companies to retire it and that’s why we’ve got a disproportionate share of companies that are making very hard but very important technology.

And also just hiring the best people on the planet. There are things that we do that only a handful of people know how to do. People who have worked at US National Labs, have built really critical technology, who don’t get vertigo thinking about this thing that needs to exist. ‘It’s going to take a billion dollars, but I know how to build it, and I can prove I know how to build it.’

We’ve got a wildly disproportionate share of the world’s most important deep-tech companies in the portfolio. And every time I work with entrepreneurs like that, I ask them who are the smartest people they know, and I go and call those companies. The PsiQuantum folks pointed me to a company that has since figured out a way of making an MRI machine 100,000 times more sensitive so you can directly image cancer metabolism with an MRI, which has never been possible before. Another company were professors that worked with the PsiQuantum software team. They have a company that’s making quantum algorithms 40-million times more efficient. Really clever people know other really clever people. Sometimes those brilliant people are also making great companies. That’s been a process that’s worked repeatedly.

Having known some of the great entrepreneurs of the era, what are you looking for in a founder?

A good topical example is [PsiQuantum founder] Jeremy O’Brien, who is from Perth. He had many, many years working in quantum computing. When he showed up, he had all the characteristics I look for. He was a deep domain expert. He understood how to build a quantum computer better than anybody on Earth. He was really driven and really willing to say, ‘Look, if I had to build the machine today, it would be a million times too big. But let me tell you how we get there’. He wanted to translate his life’s work into something important. He and I both believe that quantum computing is probably the most important technology since fire. He was visionary enough and clear enough about what he wanted to do, that we felt there were good technical reason why what he was talking about could be done.

But he’s also managed to attract this incredible multidisciplinary team, and they have been executing flawlessly for the last eight years. You need people that really want to make something happen; that are driven by a vision to fly a hydrogen plane, or to transform how the Australian economy works, and how we create metal, and just people who want it really, really badly because it’s hard, and people are going to kick you in the shins, and it’s going to be brutal, and it’s going to be a long grind to get it done, and if you really don’t care about it, not gonna happen.

Playground’s Unicorns

| Company Name | Industry | Notable Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| PsiQuantum | Quantum Computing | Developing quantum computers using photonics |

| Skydio | Drones and Robotics | Autonomous drones |

| Mosaic | Data Analytics and AI | Acquired by DataBricks for more than $1 billion |

| Relativity Space | Aerospace | 3D printing for rocket manufacturing |

| Ultima Genomics | Genomics | Ultra low-cost genome sequencing |

| NextSilicon | Semiconductors | Optimizing computing power for AI and HPC |

| Virta Health | Healthcare | Reversing type 2 diabetes via telehealth |

| Fabric | E-commerce and Logistics | Innovating micro-fulfillment for e-commerce |

| Branch Metrics | Deep Linking and Attribution | Mobile growth and attribution platform |

| Sentropy Technologies | AI to remove online hate & harassment | Acquired by Discord after knocking back US$10b Microsoft offer |

Where did it all begin for Peter Barrett?

I grew up in Sydney. Went to James Ruse [a selective high school]. During first year at Sydney uni, I started a hardware and software distribution company with some friends. At one point I went to Macworld Expo in the US and a little company called SuperMac made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. They were the first to create coloured screens for the Macintosh.

When I was still at school, I’d written a security program, an encryption program that SuperMac sold and that got me a visit from the National Security Agency. They explained to me what changes I would need to make in order to make it exportable … They thought that I should make it easier to break. It would make their jobs more difficult … We elected not to change it, but we never shipped it overseas.

I met one of my current business partners, Bruce Leak, there when he was working at Apple. I eventually worked with him on QuickTime. I wrote the first video codec way back when.

I stayed at SuperMac until it went it public and then started my own startups in Silicon Valley. The first one I did was a video-game company called Rocket Science. Steve Blank, a fairly famous Silicon Valley figure, was my mentor. I went and raised venture capital and built the company, built some really interesting games, but it was not a commercial success.

And Elon Musk?

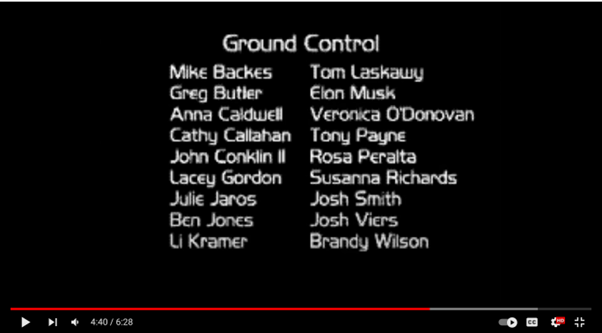

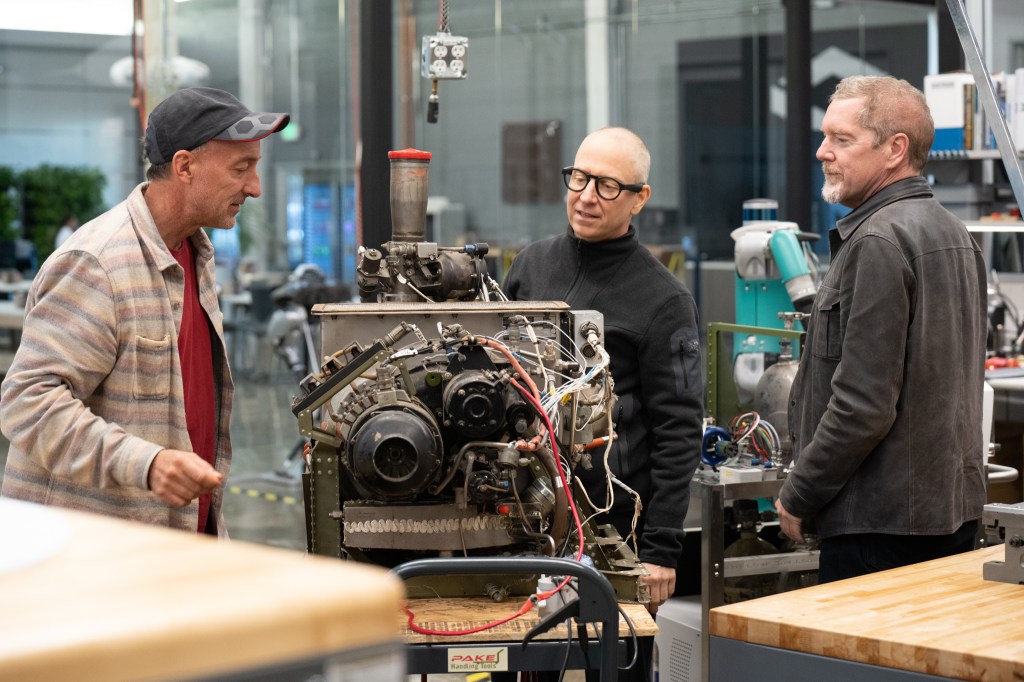

I gave Elon his first job as a software engineer [in 1994]. If you type ‘Elon Musk Rocket Science Games’ into YouTube, you can see some of the games and get a sense of what he was working on. Really, really, really clever kid. Really sweet, sort of nerdy, but very accomplished for his age. I think he was 19 or 20. And he was surrounded by a bunch of really good artists and engineers. It was clear that he was going to be an entrepreneur: deeply curious; really interested in how the world works; really interested in science, deep affection for Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. I introduced him to the VC that funded Zip2 [founded by Musk and his brother in November 1995].

I think what he’s done with Tesla and SpaceX is extraordinary, and there is a lot of his systems thinking in there. I sort of don’t know why he’s obsessed with X and where the shift into politics and the kerfuffle around X came from, but, like Bill Gates, people don’t appreciate what a great engineer he was … Those guys are models for what I see in great founders, what I look for. So many of our CEOs [funded by Playground] have that broad technical depth, but also are driven to make something happen, to translate their life’s work into a big company that provides utility for lots of people.

Related

How did you get to know Bill Gates?

Bruce Leak who I’d worked with on QuickTime co-founded a company called WebTV [in 1995, enabling access to the internet via televisions]. I wrote the browser for WebTV and when they were acquired by Microsoft for $500 million, I joined Microsoft as a distinguished engineer and spent 13 years working around digital video, television streaming … Everybody’s familiar with streaming now, but that Microsoft product was first of its kind. Microsoft was an incredible journey. I got to spend quite a bit of time with Bill and Steve Ballmer, both of whom I admire greatly.

You thought it was clear from the start that Musk was going to be an entrepreneur. Why?

One of the people at Rocket Science, Ron Cobb, designed the DeLorean from Back to the Future. He designed all of the human technology in Alien. He was production designer in Conan the Barbarian. Brilliant guy. I remember him having a conversation with Elon about a laser pistol that was powered by bullets that were super capacitors. You could load the laser pistol with a clip of charged capacitors, and have all of the dynamics of the normal firearm. And they spent a lot of time talking about the Moon. We had a game called Loadstar which happens on the Moon. How you design Moon bases. Why do the domes need to be round? What would be the architecture of a Moon base? Just the guy’s deep, deep curiosity. Why does that work that way? How could it be different? Why wouldn’t you do it that way?

Great entrepreneurs are deeply serious, deeply driven, and the third aspect is humility. They are often the smartest guys in the room, and brilliant in every domain, but the best entrepreneurs are good at learning about things that are out of their domain, and being open to listening. That ability – to want to keep listening and keep learning – is incredibly important. Gates is that way. He has a ferocious appetite for finding out things he hadn’t previously known. You cannot stop recognising that no matter how brilliant you are, nobody knows anything yet.

What got you into venture capital?

After 13 years, it was time to do something else. I tried to take a couple of years off. That didn’t work. Founded another company, CloudCar, with Bruce and some other friends that was looking at building automotive software. And the challenge there was the only person in the US motor industry that understands software is Elon Musk. You could build extraordinary software, but when it came to actually getting paid for it, Detroit couldn’t distinguish between buying seat covers and buying software. So CloudCar wasn’t particularly exciting. I realized that what I really wanted to do was build the venture capital firm I wished I had when we were out raising money for startups. With four co-founders, we created Playground in 2015.

Tell us about Playground.

Playground is a deep-tech venture firm right in the middle of Silicon Valley. We’ve got US$1.2 billion under management. We have more unicorns than the entire Australian venture system combined.

How on earth do you get US$1.2 billion to come on board?

We have that US$1.2 billion over three funds. You deploy it into companies that can do useful things. Then, if the companies succeed, people give you more money to do it again. In our first fund, we invested in a company that made the first AI hardware accelerator, a company called Nervana Systems [bought by Intel for $408 million in 2016]. We invested in a company that Elon uses to print rocket engines on Starship. We also invested in PsiQuantum [valued at US$3.15 billion before announcing deals with the Illinois, Australian and Queensland governments to build quantum computers in Chicago and Brisbane]. I met them when they were three people. Those three are among about 20 companies in the first fund.

Then we raised the second fund which has humanoid robots, other kinds of next-generation computing, AI companies, engineered biology. We’re flying a 50-passenger hydrogen plane that went from my first investment to flying in two years. [Universal Hydrogen collapsed after this interview, having burned through almost $150 million in capital and being unable to raise more.] But we don’t do dating apps, we don’t do Bitcoin. We’re trying to make things that are really important. And in Fund Three we have a really amazing Australian company [Element Zero] that can make iron and lithium and a whole bunch of metals without emitting carbon – and do it in Australia. We are investing a lot more in Australia because I think it has a central role to play in decarbonisation and has the world’s best talent in quantum and electric chemistry and a whole bunch of different domains.

The Australian economy is, in terms of complexity of our exports, it’s right there between Pakistan and Uganda, but in terms of research and in terms of science and engineering, it’s fourth in the world. There’s huge amounts of capital in our super funds that we’ve got to figure out how to translate into big, valuable companies. So people like me and Jeremy O’Brien [PsiQuantum CEO] don’t leave Australia, but they build the companies here. And so I’m trying to spend a lot of time and energy figuring out how to enable the super funds to underwrite deep-tech investment and to build the kinds of companies that right now get built in Silicon Valley.

We’ve got to have an environment where our best scientists and engineers have more choices. Like, if you’re the main expert in quantum error correction, you can either move to Silicon Valley or become a barista.

I mean, the Future Fund was a big investor in one of our earlier funds … We’ve got this incredible resource in the superannuation funds, which is, at three and a half trillion dollars, the fourth largest pool of capital in the world. But we’ve got to spend it on something other than real estate. There’s only so many airports you can buy. We’ve got to invest it into deep tech because we have to diversify our technical and industrial base.

Have you been taking pitches from start-ups while you’ve been here?

Yeah. I’ve talked to a few folks, and I can’t tell you which, but I saw one yesterday. It’s absolutely 100% a world-class company with a world-class CEO, with world-class technology … And you know, there’s a rich ecosystem that gives you the path of what a start-up is, and Australia is relatively early in that process … There’s nine unicorns in total from Australia. So it’s early, but I think all the ingredients are here. And there are some very good venture capital firms here, like Blackbird and Square Peg and especially Main Sequence. Any deal they’d do would be very highly correlated with any deal we’d do … We’re going to be making more investments in Australia. We’re going to do a bunch of stuff in mining. We’ve got companies who are operating with BHP and Rio. So I’m going to be here a lot. We’re going to be writing cheques into quantum startups, into electric chemistry and bio-engineering startups.

Where is home now?

I live right next to Stanford University and right next to Playground, right in the heart of Palo Alto.

Do you still have parents here?

Mum and Dad are still in Wahroonga [Sydney]. I spent time with them last week. My brother and sister are still here. Every time I come back, I think inevitably I’m going to have a house here too, because I love the ecosystem. I love the people we collaborate with. It’s not as long a flight as it used to seem.

James Ruse High [A selective school with a strong academic reputation in Sydney]. Did it help you?

Absolutely. What people don’t realise is, if you have incredible teachers in early high school, that can really change your expectation about what’s possible. And I had a couple of amazing teachers at James Ruse, lifelong friends there. They were brilliant teachers committed to education. My wife’s a school teacher. She’s deeply committed to education. We actually founded a school in the backyard of my house in Palo Alto that now has about 300 students – K-through-eight – focused on: How do we produce well-adjusted students that know about the world, but also know how to deal with the complexities and social pressures of growing up? Education is the most leveraged thing, and we’ve got to figure out how to pay teachers more and allow those extraordinary people to influence kids. It’s got to be early. University is great, but you kind of know who you are and what you want before you go to university.

What’s your school called?

The school is called Synapse, in Menlo Park, California, right near where I live. It started with six students in my backyard, and now has some of the fanciest people in the Valley send their kids there.

Are you close to exiting on any of your investments?

There are already companies that have exited. There will be a lot more over the coming year as the IPO market comes back. But, for example, two years after we led the Series A for [AI start-up] Mosaic, that was acquired for US$1.3 billion [by DataBricks]. In all three funds we’re starting either exits or near exits. I think PsiQuantum is going to be probably the longest because it takes 10 years to build a quantum computer, but some of these things have got exited in a handful of years, and that will continue.

What percentage of Mosaic did Playground own?

I can’t tell you, but I can tell you we led the Series A. In 100% of our Fund Three companies, we are the largest shareholder, and we are the largest shareholder in most of our unicorns. We like being the first cheque in for both the seed and Series A rounds. And generally, we are at or near the largest ownership of the companies. So we were first money in and largest shareholder in PsiQuantum, for example.

What percentage of Playground do you own?

We’re a little bit unusual in that Playground Global isn’t just owned by the partners. We have 40 people, all of whom have some amount of ownership in the fund. Normally, venture funds have a small team and the returns are concentrated in just the partners. We spread it around a little more. Playground itself was a startup, right? … But look, the economics are that if you build great companies, it’s easy to make a ton of money for your investors and your family.

How to play it

Belz Family & Associates [BFA] offers “sophisticated” Australian investors a chance to invest in Playground.

BFA was founded by Jonathan Belz who came from Goldman Sachs then the Smorgon family office. He was inspired to set up BFA, he says, when he saw how hard it was, even for a big family office like the Smorgons, to get in on the cutting edge of venture capital with companies that were creating valuable new products, rather than just financial derivatives and the like.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this can only be multiplied by many factors when you go down to smaller families and advisors who are just busy putting traditional portfolios together. It’s just difficult to see what’s going on at the pointy end of venture.”

Through an introduction he met Peter Barrett. “He’s an incredible guy,” says Belz. “You rarely get someone who is so technically apt, but so commercially driven as well … What struck me as well was he was very humble with that approach. He works with big egos. He’s had fantastic success himself already but he doesn’t take that all on in a way many others have. And just an unbelievable eye for where the world needs to go.

“Just seeing how trusted and respected he is by the companies which are themselves savants and geniuses changing civilization. That combination is pretty special. Belz has set up structures that allow “sophisticated investors” [defined as someone with gross income of more than $250,000 or net assets of at least $2.5 million] to get in on Playground.

“We aggregate investment sizes as low as $100,000, and we do it in a single purpose vehicle in that it only invests into the Playground Fund or the Playground co-invest, depending on the deal.

“We do it through a nominee structure. It gives the investors the same equitable position as being on the cap table, but we underwrite the position and manage it for investors.”