But an endangered wildflower could stand in the way. It’s a green vs. green dilemma and there might be a solution.

This story featured in Issue 10 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

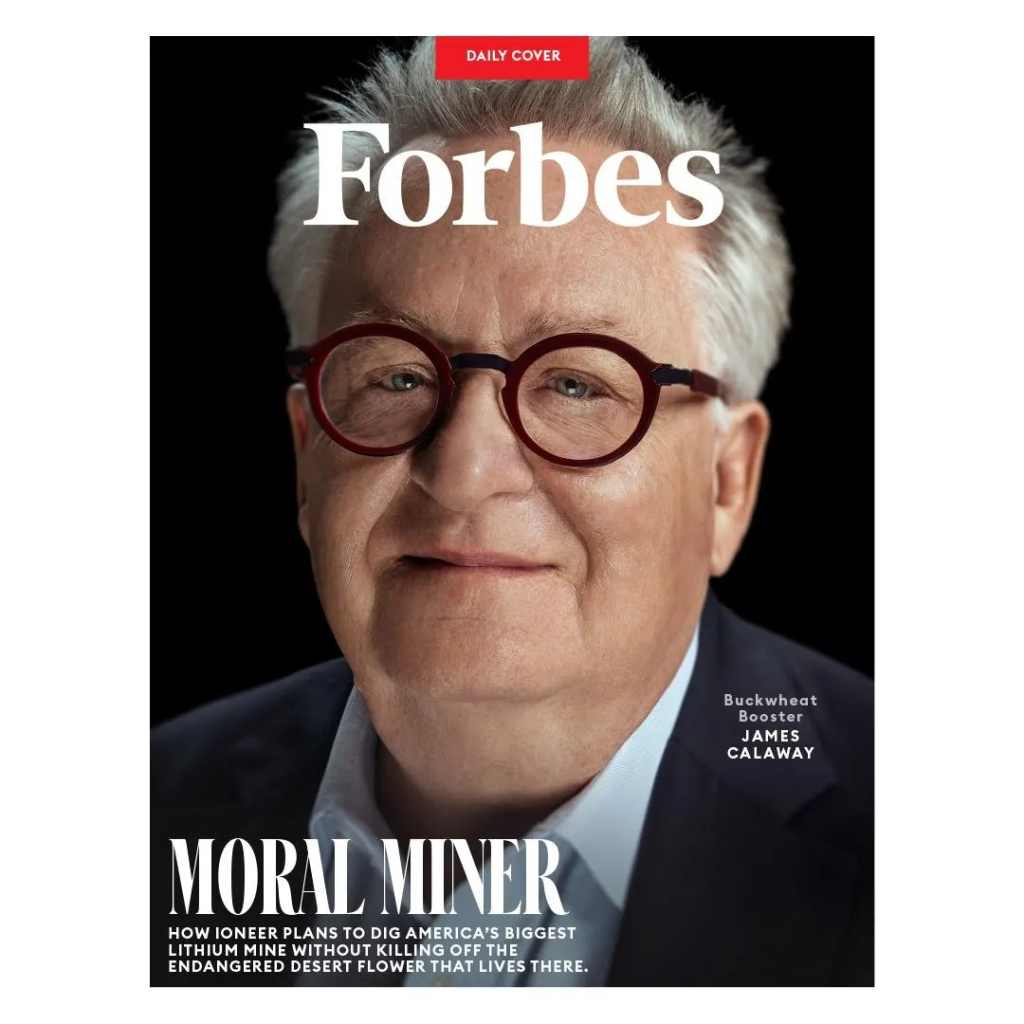

“Rhyolite Ridge is an amazing deposit. There’s not another one like it in the world,” marvels Bernard Rowe, an exploration geologist and CEO of Australian mining company Ioneer. Rowe, 56, came to Nevada prospecting for gold and copper, and was struck by the Ridge, a volcanic rock outcrop in the southwest part of the state. He collected ore samples, which proved to have high concentrations of lithium and boron. The discovery prompted a call to his friend James Calaway, a Texan who had developed one of the world’s biggest lithium mines in Argentina.

After due diligence, in 2017 they secured enough mineral rights in Nevada’s Esmeralda County to potentially produce more than 100,000 tons of lithium a year—enough to make billions of iPhone batteries and millions of electric cars. Now they just need to start digging.

Rhyolite Ridge is on federal land, requiring permits from the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management.

But given China’s dominance in lithium (it refined 75% of the world’s 1 million tons of 2023 production), Calaway, Ioneer’s chairman, believed his project would be favored politically. After all, the U.S. currently produces just 7,000 tons annually.

There was a complication: a six-inch-high desert wildflower with yellow blooms called Tiehm’s buckwheat (Eriogonum tiehmii). The heart of this rare perennial’s 900-acre range is right where Ioneer intended to mine.

So the company worked with desert botanists, including researchers at the University of Nevada, to devise a plan to dig up and “translocate” thousands of plants to similar terrain nearby. “Our analysis showed that it should work,” Calaway says.

He didn’t get the chance to try. After 40% of the native population, about 17,000 plants, died mysteriously in the summer of 2020, environmentalists petitioned for its inclusion as an endangered species.

Undeterred, Ioneer submitted revised mining plans in early 2022. Months later the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service officially designated Tiehm’s buckwheat as endangered.

Calaway’s desert bloom dilemma exposes a critical challenge facing policymakers. Who prevails in green vs. green, when one environmental concern comes into conflict with another?

Is digging up enough minerals like lithium, neodymium and dysprosium to enable the electric vehicle transition worth killing 44,000 small plants growing in the middle of the Nevada desert? Should we erect offshore wind turbines if they kill whales and seabirds? If so, how many dead whales is too many?

“Everyone wanted this to work, for the good of the world,” Calaway says. That includes the Biden Administration, which announced in 2023 that it would lend Ioneer $700 million for the project if permits were approved.

But the mine’s chorus of detractors, including the Tucson, Arizona–based Center for Biological Diversity, were too loud to ignore.

“It was too risky for the government to sign off on,” Calaway laments. “I had a very hostile view toward this plant.”

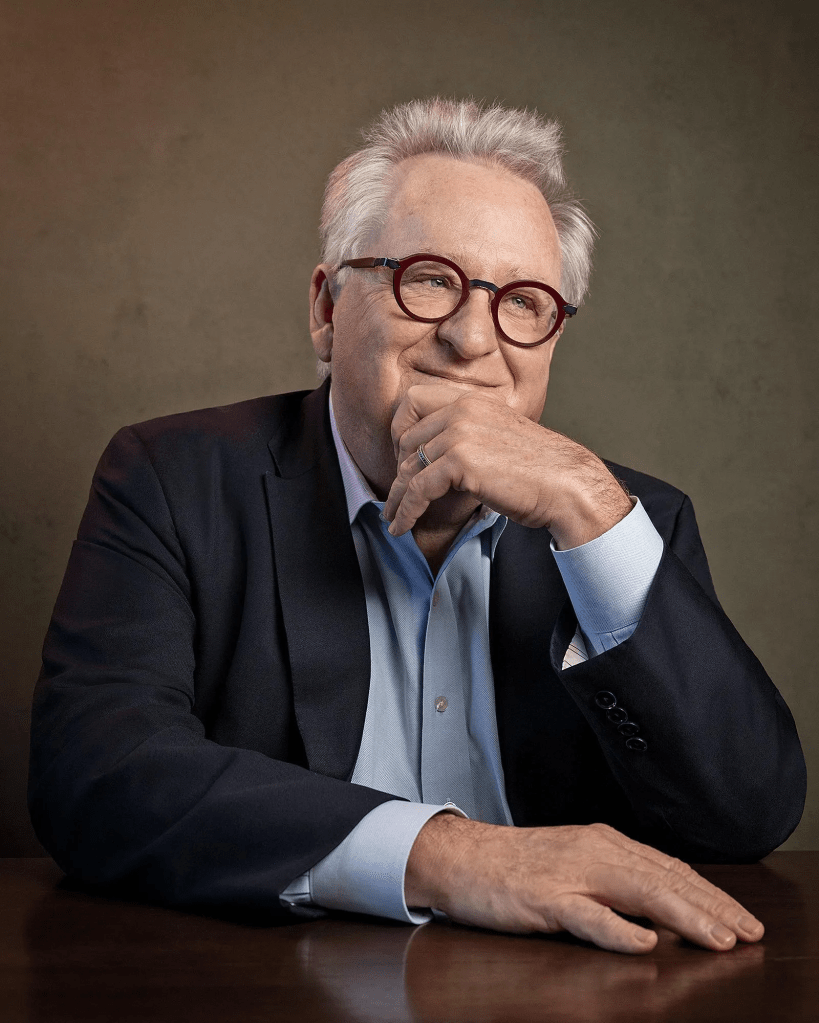

Calaway, 66, is not your typical liberal-bashing Texas energy executive. Though his father was an oilman, he was also a lifelong member of the NAACP and chairman of trustees at the left-leaning Aspen Institute.

Calaway graduated with an economics degree from UT Austin and a master’s in philosophy from Oxford in 1981 before an executive career at various mining and wind power companies. He says the ultimate solution to Ioneer’s buckwheat conundrum required psychological reframing.

“We shifted from hostility toward this thing that was an impediment to us to embracing the plant as a symbol,” he says. “We decided we were going to be responsible for taking care of these plants. Once that happened, everything changed.”

Ioneer redesigned the mining pit around a strict “no touch” policy, with a buffer zone of hundreds of feet around all but a handful of plants. Instead of leaving an island of Tiehm’s buckwheat flanked by an open-cut quarry, they shifted some operations a half-mile away.

Then they doubled down on an ambitious biology project.

Outside Carson City, Nevada, Ioneer has botanists operating a 1,600-square-foot greenhouse in which they cultivate buckwheat, collect seeds and insist that the plant can grow happily in slightly alkaline-enriched garden soil.

Turns out thirsty squirrels killed those plants in 2020 while digging up roots for moisture.

Ioneer intends to seed them in similar soils nearby, and as a precaution has banked thousands of seeds at the Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank & Plant Conservation Program at Portland State University in Oregon. “The plants’ best chance of survival is by our work,” Calaway says.

Detractors disagree.

Benjamin Grady, president of the Eriogonum Society and a professor at Wisconsin’s Ripon College, fears that approving the mine will be a death sentence for Tiehm’s buckwheat, one of the most finicky of 250 known species in the genus. “There’s a reason why after countless generations of evolution it doesn’t grow anywhere else but in these specific conditions.”

Unlike Argentina’s lithium mines, which amount to vast brine evaporation ponds that concentrate lithium over time, Rhyolite Ridge will be what’s known as a hard-rock mine, meaning Ioneer intends to blast, pulverize and sift through megatons of material.

It’s an expensive process, but the presence of boron compounds (used to strengthen insulation, plastics and glass) makes it economical, says Thomas Chandler, lithium analyst at SFA, a metals consultancy in Oxford, England.

Selling boric acid, he calculates, should effectively reduce Ioneer’s costs from $9,000 a ton of lithium concentrate to $2,500—a hefty margin given the current $14,000-a-ton spot market price.

Trouble is, Rowe says, “there’s no recipe for lithium-boron deposits. If you’re mining gold or copper there are countless books.”

So Ioneer had to figure it out. Calaway interrupts lunch at Houston’s Italian gem Johnny Carrabba’s to hold up a diagram of his future lithium plant, engineered by Fluor and ABB, scaled up from a $20 million pilot they built in 2019.

It will use little water and generate all needed steam and electricity via chemical reactions. The first phase will put out 22,000 tons of lithium carbonate powder and about 175,000 tons of boric acid per year.

In time Ioneer envisions multiple identical plants on site. “Importantly, it helps make the U.S. less reliant on the rest of the world,” Calaway says, an obvious reference to China.

Fully operational, Rhyolite Ridge would be one of the largest lithium mines in the world but is still just a raindrop in a pond. SFA sees lithium demand nearly trebling by 2030 to 2.8 million tons a year.

Like other fledgling mining operations, Ioneer is a volatile microcap stock. It first listed on the Australian Securities Exchange in 2007 and is now available as an American depositary receipt.

According to SEC filings it has $50 million in cash, no debt, and in 2023 burned through $40 million. Its market cap of $300 million is down 80% since mid-2022.

John Arnold, a billionaire energy trader, owns 13% of the stock, and the company has already secured a $500 million equity financing promise from Sibanye-Stillwater, a South African mining giant.

If the Bureau of Land Management gives the nod to Rhyolite Ridge (a decision is expected by mid-2024), it would be the first new mine on federal lands approved under the Biden Administration. Ioneer hopes to begin producing lithium by the end of 2026.

Buyers, including Ford and Toyota, are already lining up. Says Rowe, “I wish we had gotten started sooner.’’

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.