It’s taken more than 20 years, a bucket of grit and a rare ability to find help across the globe, but Daniel Timms is poised to make heart transplants a thing of the past.

This story featured in Issue Seven of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Billy Cohn is a world-renowned heart surgeon at the top of his game. He has a side hustle with Johnson and Johnson as vice president of medical devices. He has about 200 patents on his heart-related inventions that he has spun into six start-ups – “some wildly successful”. But he quit them all in March to join a cult. He’d fallen under the spell of a Brisbane engineer, Daniel Timms, who turned up in his office a decade earlier with an artificial heart – the BiVACOR – in his backpack and the audacity to suggest he’d solved a problem that had defeated the world’s best since 1969 when the first artificial heart was put in a human chest.

Despite billions of dollars spent over half a century, the hubris of all such devices and their inventors has been exposed by the human body’s relentless demand for 52 million heartbeats a year.

So here was Cohn at the Texas Heart Institute – where that first artificial heart had been built and where many such devices had lived and died – squeezing the unshaven Timms into a half-hour diary slot on a busy day in 2011.

Four hours later, they are still talking.

“I’m full-time with BiVACOR now,” says Cohn, “because I think this is my Wright-brothers moment. Here’s my chance to change the world, and I will do everything I can to make sure it happens.”

Cohn was the first person to use the word “cult” in association with Timms. “You’ll never meet someone with a more intense work ethic, more distilled essence of brilliance, more capable of listening to others and realising what he doesn’t know and trying to put together a team and instilling allegiance in them than Daniel Timms,” says Cohn.

Timms’s journey – which began with a desperate attempt to build a device to replace his father’s failing heart – is nearing the end of the beginning. The device he invented looks like it will become the world’s first permanent artificial heart and is expected to be in human chests next year. All the corporate infrastructure required is manifesting clinical specialists, manufacturing partners, quality assurance people and a human resources department.

BiVACOR raised $US18 million in March to bring its total backing to about $US60 million. But, for most of the devices’ existence, it’s been Timms persuading the world’s finest from Brisbane to Tokyo, Taipei and Aachen, Germany, to help him – to join the cult of Daniel Timms.

A million smoking craters

Timms was a mechanical engineering undergraduate at Queensland University of Technology in 2001 when his plumber father, Gary, developed heart failure after a mild heart attack. “It was like, ‘Well, maybe I can spend my time doing something that might help him,’” Timms recalls.

He read up on artificial hearts and blood pumps and decided to do a PhD on it. He saw that all previous attempts had failed because the demands of valves opening and closing to pulse blood through the body were too high; no machine could withstand it indefinitely. Perhaps, he thought, a continuous-flow pump could do the job better.

He wasn’t the first to have that insight, but he was the first to believe it could be done for the whole heart – and not just as an assistant for the left ventricle. And maybe he could drive it with a single moving part – a spinning disk. Think of a waterwheel that’s been split down the middle so that half the blood it pushes goes to the lungs, and when it comes back to the heart, the other half of the waterwheel pushes it out to the rest of the body – one moving part pushing two streams.

Timms’s dad had always been a tinkerer, so when Daniel told Gary his idea, the two set about approximating the human circulation system using pipes from Bunnings so they could test prototype heart pumps. “Without a doubt, his knowledge of putting that stuff together really helped to accelerate our early ideas and bring it to a proof-of-concept form,” says Timms.

Timms hit upon the idea of having his one moving part magnetically levitated – a maglev system – so there was zero wear and tear.

He went to Japan, which had led the world in maglev train technology since the 1960s, to learn how that worked. He couldn’t pay for help, so he worked on other people’s projects in exchange for their help on his. Students and professors helped design his magnetically floating disk.

All the while, there was resistance from doctors about the notion of a heart without a pulse. “The medical community said, ‘That’s never going to work. The body needs a pulse.’ Nobody even went down that pathway,” says Timms. “We thought, ‘Why not? It’s just a system that needs blood flow.’”

“Why does it matter if it’s got a pulse or not? It just needs the blood to go around. So, we came up with a completely different angle. ‘We don’t care what you think the body wants. What it wants is blood flow.'”

Daniel Timms, BiVACOR founder

The work caught the right eyes at the university and before long, Timms had been given a room at Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital, the largest cardiac hospital in Australia.

John Fraser was a young heart specialist who’d just commandeered a room to start a research group looking into improving heart transplants. A music fan, he was annoyed by the racket coming from next door. He knocked on the door and could tell the bloke who answered, surrounded by a mess of pipes, wasn’t a doctor. “Sorry about the noise.” They talked soccer and hearts.

“I could see he was a brilliant engineer with a fantastic idea, but not really connected with doctors or patients,” recalls Fraser, now a professor. “I said, ‘I’ve got an animal lab if and when you get to that stage.’”

Fraser saw Timms work impossibly long days, sacrificing a “normal” life at the altar of this goal. His father was dying. Time was running out.

Timms was awarded his PhD. He kept going.

He and Fraser collaborated more. “We received some grant money,” says Fraser. “It was easier for me to get it because I’m a medic. I had a wage. Daniel had no wage. I went and bought a sofa for Daniel to sleep on. For nine months, he slept in my office. For years after, I’d find a pair of jocks or dirty socks. It was very much a boys’ research program. But together, we brought on the clinicians, the engineers, the blood scientists and the politicians to get it moving.”

But resistance to the concept remained. “We went to speak to a senior surgeon once about this concept of a total artificial heart without a pulse,” recalls Fraser.

“He was a classic older surgeon. But he thumped the table and said, ‘You guys don’t understand what you’re talking about. No one’s going to live without a pulse. Get out of my office.’”

John Fraser, heart surgeon

As we progressed, I got a message from that same surgeon saying he’d like to be involved. ‘I said, I think we’ll be fine, but thanks for offering.’”

Funding was nearly impossible. “There’s a million smoking craters of attempts to develop a device like this,” says Timms. “They’ve poured 10s, 20s, 100s of millions into them, and they all end up the same.” But the hospital coughed up for a wage now, and the Prince Charles Hospital Foundation sold strawberries at a local fair to get him money to buy stuff at Bunnings.

In 2006, they implanted it in a sheep and proved it could work. His father took a turn for the worse. Gary Timms was admitted to Prince Charles and was cared for by Fraser, two minutes’ walk away from where Timms was maniacally building. He doubled down and, for two months, barely left the lab, barely eating, barely sleeping, just wandering down to visit Dad. He knew it was naive, that he’d never make it in time, but he did it anyway.

The last time Gary was admitted to the ICU, Daniel drove him to hospital. Daniel was getting on a plane to Germany the next day to meet potential collaborators, but he asked Gary if he should go. “You’ve got to get there,” said Gary. “This is what we’ve been working for.” Daniel went, and Gary died a few days later, another victim of an absence of suitable donor hearts.

In 2007, electrical engineering student Nick Greatrex had been trying to figure out what he wanted to do for his PhD. He started on another blood pump idea and got to know Dan Timms. “No one seemed to have the picture down. But talking to Daniel, I thought, ‘This guy knows what’s going on.’”

Greatrex set about figuring out how to have Timms’s pump respond to changing demand – for example, when the user starts jogging or goes to sleep.

Greatrex, still in the cult 16 years later, has never doubted that Timms’s heart would work. “Naivety is bliss. But I didn’t think it could fail. It was such an elegant solution to a complicated problem.”

And like others in the project, he puts it all down to Timms’s passion and 360-degree view of the problem.

“He can talk to a heart surgeon, then talk to an intern about some electrical thing, or rotor dynamics, or the interface of materials to make sure the pump is performing the way it is.”

Nick Greatrex, on Timms

Timms moved to Germany soon after to work with the Helmholtz Institute – a leading research centre for cardiac devices – trading his time working on their blood pump in exchange for help on his. Greatrex followed, being paid to work on the German institute’s projects but, like Timms, also working on the BiVACOR.

In 2010, the resulting device was implanted in a sheep by Fraser. “We didn’t know then how to connect it to the circulatory system,” says Timms. “We had this beautifully designed engineering pump, but the connection system was unsuitable, so we couldn’t access the sheep’s blood to pump it around. That was a major limitation.”

He found a group of experts in the field in Taiwan and enlisted their help. The resulting system was implanted in a cow that lived for a couple of hours. “That was one of the biggest steps for us. To show the pump could support an animal for a couple of hours, meant it was a feasible approach.” It had taken a decade.

Out of the shadows

Timms and Fraser co-founded BiVACOR in 2008. Three years later, they were ready to present the idea to the world at a major heart conference in Paris. They needed patent protection first. But Queensland Health said it owned the patent. BiVACOR disagreed but eventually yielded to the government.

“And we said, ‘Can you please write the patent then so that we can present in Paris,’” recalls Fraser. “It was like a scene from Utopia. Having fought over who owned it for months, Queensland Health said it wasn’t worth patenting – Daniel had sunk his lifeblood into this device. We said to Queensland Health, ‘You don’t think a bionic heart is worth patenting? Sign a letter saying that, and we’ll call it quits.’” BiVACOR got the patent.

Timms had been going to these conferences worldwide for the past decade, sitting up the back, too insignificant to ask a question or have one asked of him. But suddenly, he was on stage telling the world’s brightest where they were wrong.

Texas Heart’s Dr Billy Cohn picks up the story of his colleague and mentor, Dr Bud Frazier, who was in the audience: “By this point in his career, Bud’s gotten to be a bit of a curmudgeon. He was in his early 70s but is the ultimate domain master. He knows more about the field than anybody. Usually, when somebody gives a stupid presentation, he goes up to the microphone in his fedora and carves them a new one, telling them all the stuff that’s been done before that they don’t know about. ‘It’s a shame you haven’t read the literature.’

“Daniel gives his presentation, and Bud Frazier walks to the microphone, and everybody’s thinking, ‘Poor kid. He’s going to get it.’ And Bud says, ‘Well, I don’t know what the future of this field is going to be, but I suspect it’s going to be something like you just showed here.’ There was an audible gasp. He never says anything nice.

“Bud talked to Dan. ‘When are you going to come to Houston and talk to Billy [Cohn]? Billy’s the device guy.’”

So Timms flew to Houston and visited Cohn. Through the course of that “half-hour meeting” that went for four hours, Cohn was flabbergasted to learn that Timms’s team was spread over the world, with collaborators in Brazil, Germany, Japan, Taiwan and Australia all doing it as a second job, with no backing, galvanised by the force of Timms’s passion. “It was hardly a company,” says Cohn. “It was more of a big science project. He’d done it over a decade with a few grants totalling a couple of hundred thousand dollars.”

Cohn joined the cult right then. “You’re not leaving Houston,” he said. “What would it take to get your team here?”

“If we had 18 months and the whole team in Houston, we could develop a device we could put in a cow,” said Timms.

“How much would that cost?”

Timms already had the answer. “US$2.5 million.”

‘We’ll kill you if you take our money’

Timms brought the device and the connecting systems to Houston in 2012 to try it on a cow. “That cow stood up, looked around and goes, ‘What’s the big fuss?’” recalls Timms. “They (Cohn and Frazier) realised that this approach was what they’d been looking for the last five decades.” The cow lived less than a day with a device made in a garage, but it was enough to show the potential. As always, Timms was there for the autopsy to see what went wrong – where they could do better. In this case, it wasn’t the device but a clot in the interface where flesh met metal.

He took the idea to the Australian biomedical venture capitalists Brandon Capital Partners in 2012. “They said, ‘Our money’s too expensive for you. We need a return earlier than you’re going to be able to give it to us, so we’ll kill you if you take our money.’ It’s hard to hear that, but they were right. They did me a favour.”

Timms needed another way. He was in Japan making the next prototype when Cohn called. “Hey Daniel, I’ve got this investor interested in giving the program a couple of million dollars.”

Timms had heard it all before. “Who is it, and what are they talking about?”

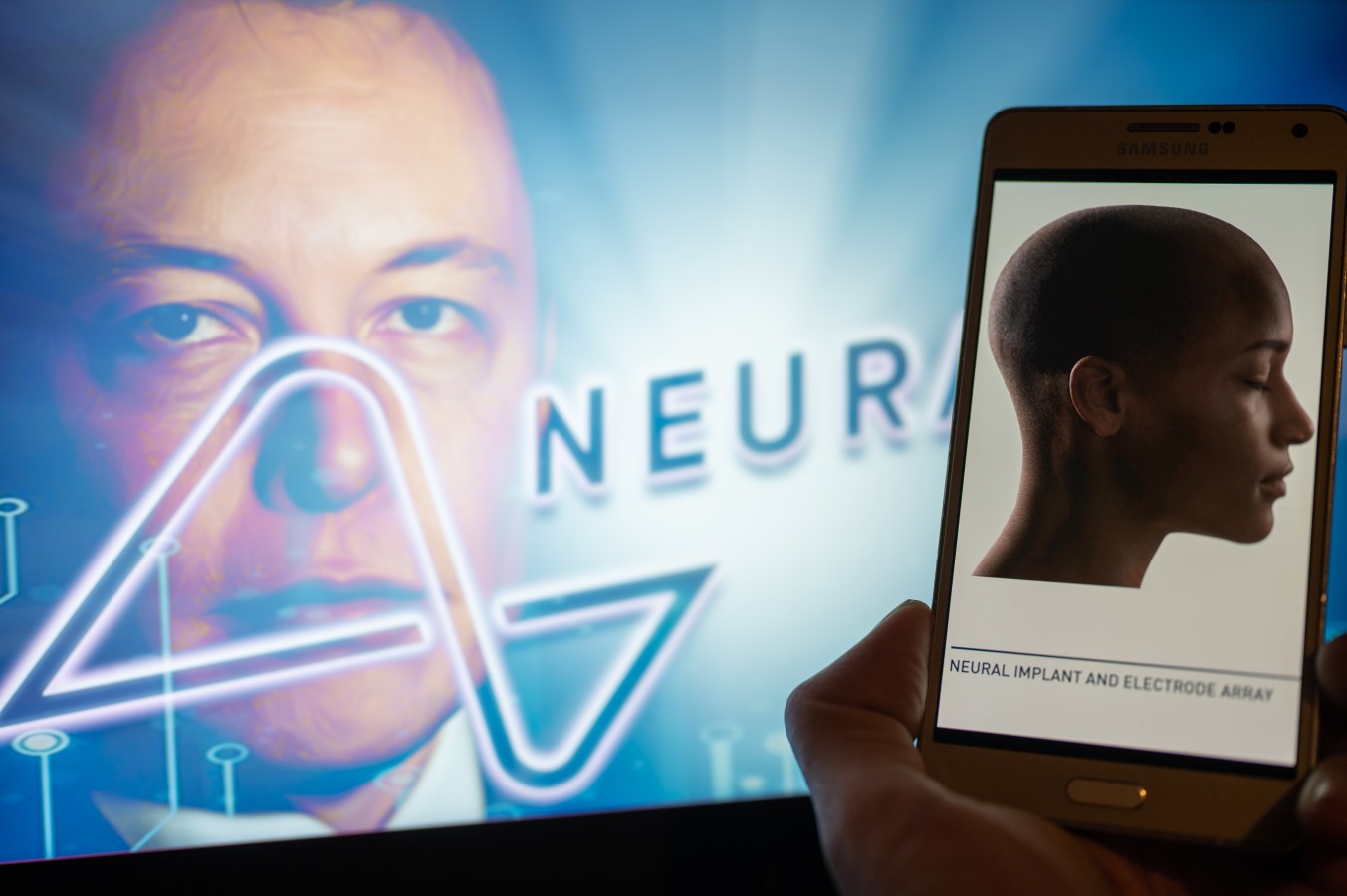

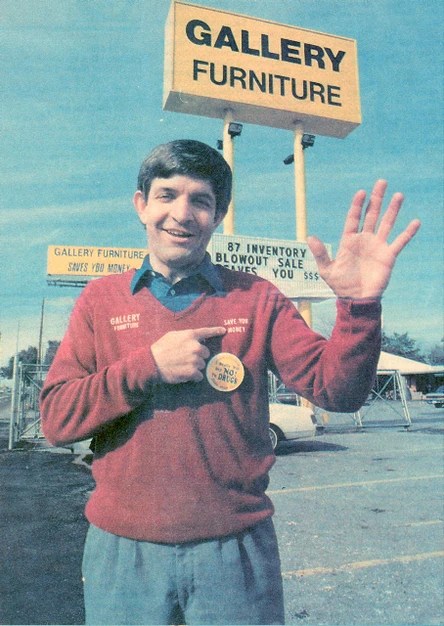

“His name’s Mattress Mack. He’s a furniture salesman in Houston.”

“Billy, you want me to fly to Houston and meet with a guy called Mattress Mack? Are you sure?”

Cohn explained that he’d done an emergency implant on the brother of Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale, founder of a Houston retail chain, Gallery Furniture. He was keen to pay it back.

“I boarded the plane expecting it to be a complete shit show,” recalls Timms, “but I got there, and he’s super motivated to help, and within a month, he’s got the chequebook out and given us US$2.5 million.”

A frugal bunch, they stretched the US$2.5 million for three years.

BiVACOR shifted its HQ to Houston in 2013 but kept a presence in Brisbane. “I told every stakeholder, ‘We’re not taking this away from Australia. Australia is coming along for the ride.” The Australian company now employs about seven people, mostly in software development. The Queensland government continued to help. “We’re looking to expand manufacturing here, even if it’s just a supporting supplier. The Asia-Pacific is the future of where we want to push it.”

The valley of death

As the BiVACOR iterated, they kept testing in cows. The next one lived for three days, and the one after for a week. “Each time I kept saying to myself, ‘It’s never going to work,’” says Timms. “‘It’s just a crazy idea.’ But I thought, ‘If a cow lives for a month, we’ve got something.’ Because after a month, the heart must work.” That was in 2014.

A cow made a month – then two months. In 2015, they did a sheep whose body size is closer to that of women and children – too small for all previous such devices. It was hoped the device could be in humans by 2018. A cow went three months in 2016. It was time to ramp up – “to move out of the science project stage” –but Mattress Mack’s money was running out.

McIngvale continued investing after the seed funding, and Timms estimates he now owns upwards of 15% of BiVACOR. “He can’t afford the kind of rounds we’re doing now,” says Timms. “To be fair, that’s when you’re getting into the world of the new VCs, where they’re like, ‘If you’re not going to follow, we’re going to squeeze you out.’ And we’re like, ‘You’re not squeezing Mattress Mack out! I’m sorry.”

BiVACOR got AUD$3 million from OneVentures, where half the money was put in by an Australian Federal Government biomedical fund whereby OneVentures could buy out the government’s share if it was a success – effectively doubling the VC’s potential return. “If not for that, I doubt the VCs would have been involved,” says Timms. Timms moved to California, where the med-tech manufacturers were. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process was sucking up money, and then COVID-19 hit. “We got down to our last pay cheque,” says Timms. OneVentures kept bridging them.

“We were knocking on all the doors,” says Timms. “‘Where’s your clinical data? It worked in a cow, but how’s it working in a patient? Come back to us when you have the data.’ We were in a chasm where we couldn’t get clinical data without funding but couldn’t get funding till we had clinical data.”

Then they met Bihua Chen at Cormorant Asset Management in Boston. “We caught her emotion,” says Timms. “They told us later their diligence was: ‘These guys need help. They’ve got backing from Texas Heart. It looks like it works.’ It’s one of my most remarkable discussions about a VC.” Cormorant led a May 2021 Series B raise of US$19 million, which coincided with a

US government grant of US$3 million.

The way forward for BiVACOR

The money allowed them to build the clinical-grade device and jump through the FDA hoops. “Other devices had made a prototype and implanted it outside the US. They go to Paraguay or Kazakhstan, where the regulations are not as strict. We’d built a Ferrari. We were taking it to Nürburgring (the German Grand Prix track).” The FDA process is more expensive, but BiVACOR’s philosophy was that they’d need to jump through those hoops eventually, so they might as well do it straight up.

BiVACOR has submitted a plan for its first patient and is awaiting the FDA’s response. “We’re optimistic they’ll see what we see: that it’s ready for humans,” says Cohn. “They might want us to do additional animals, but we’re fine with that. I would be amazed and disappointed if we don’t put this in a human in 2024 somewhere.”

The first candidate will likely be someone with a failing heart, whose other organs are good, and who can’t get a suitable donor heart.

About 400,000 Americans die each year from heart failure. Most of them would not have been good candidates, says Cohn. They are riddled with too many other health problems. “But perhaps a third of them could benefit from it. That’s about interceding to prevent pending death but think about this – when the Wright brothers developed the first fixed-wing aircraft, and people started looking at it, they thought it might have military applications, and maybe it could take you places you couldn’t get to by ship or rail. Nobody thought there’d be 28,000 domestic flights daily.

“But aviation became very safe, convenient and economical – Boom!” He predicts that artificial hearts will be as common as hip replacement if this pump proves to have similar risk and reward, and heart transplants will be an historical footnote.

“You won’t have to wait for another person to die to harvest their organs. In the US, they estimate around 130,000 patients per year could use some kind of mechanical or pumping support. There are only 4,000 transplants a year. There’s more than 100,000 people dying that could benefit from this.”

Gary Timms would have been a perfect candidate for a BiVACOR heart, says Daniel. “When we started this, I was naively thinking we could get it done in a couple of years to help him. But now I realise that this will not only help the people who receive it, but also the ones they would’ve left behind. It’s been hard on Mum and me dealing with Dad’s absence.”

Rocky road to an enormous market

The first human trials of the BiVACOR will use the device as a stopgap to keep patients alive until a donor heart can be found. But other devices already do that. The goal is that once it has proven itself, it will stay in a patient for the rest of their life.

The economics of that look good. “The device costs about US$200,000, but the reimbursement from insurance is $350,000 for a procedure like this,” says Timms. “Strange. I was taken aback. ‘Why would the insurance companies pay so much? The reality is, if they don’t, then they’ve got the patient slowly passing away at the hospital, and palliative care is super expensive.

“The BiVACOR costs less than $100,000 to make and sells for $200,000. That’s a good profit.

Times 130,000 people, that’s a crazy market ($13 billion). That’s what gets the investors excited.”

They will proceed to a Series C raising of $50 million to $60 million to bring it to market – if the human trials prove successful – before going public. “We’re trying to keep it private as long as we can to give us the control over what we’re doing,” says Timms. “It’s going to be a rocky road. Reporting it to people who don’t understand it could be a nightmare, but if we keep our investor base well informed, then it’s good to have a closed community to help us get through the challenges.”

Mattress Mack

BiVACOR’s seed investor, Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale, is no stranger to big risks and bigger payouts. McIngvale earned his nickname as the Houston retail chain Gallery Furniture founder.

He became known to Houstonians for appearing in Gallery Furniture’s TV commercials, often dressed in a mattress costume, full of catchphrases about “saving you money”.

But his business and marketing success isn’t the only thing he’s known for. In 2022, Mattress Mack made history by placing the largest mobile wager in sports betting history, with a US$45 million bet on the Cincinnati Bengals to win the Super Bowl that year.

That same year, he made history again with the largest payout in sports betting history, winning US$75 million after the Houston Astros won baseball’s World Series.

BiVACOR’s Billy Cohn is full of respect for the furniture mogul. “He is a brilliant guy who started with just furniture on consignment in tents by the side of the road,” Cohn says. “When we have a bad hurricane, he opens up a showroom full of brand-new furniture to let homeless people or displaced people sleep on his furniture. He’s been a great, great friend.”

Counting the beats

- 1969: An artificial heart is put in a human chest for the first time. The patient lives for 64 hours.

- 2001: Daniel Timms’s father, Gary, develops heart failure after a mild heart attack spurring Daniel to look into artificial hearts for his PhD.

- 2006: Timms’ early artificial heart design is implanted in a sheep.

- 2006: Gary Timms dies of heart failure.

- 2008: Daniel Timms and heart specialist John Fraser co-found BiVACOR.

- 2010: Fraser implants a BiVACOR blood pump into a sheep, but they can’t work out how to connect it to the circulatory system.

- 2011: A new system is tested in a cow. It lives for a couple of hours.

- 2012: Timms teams up with The Texas Heart Institute, to try the BiVACOR on a cow. The cow lives for a day.

- 2012: Timms takes his idea to Australian biomedical venture capitalist Brandon Capital Partners but is turned down.

- 2013: BiVACOR receives AUD$3.86m (US$2.5m) seed funding from “Mattress Mack”.

- 2013: BiVACOR shifts its HQ to Houston.

- 2014: A cow with BiVACOR implanted lives for a month.

- 2014: A cow with BiVACOR implanted lives for two months.

- 2015: BiVACOR implanted in a sheep with a body size closer to that of women and children.

- 2016: A cow with BiVACOR implanted lives for three months.

- May 2018: BiVACOR raises AUD$3m in Series A funding from OneVentures, part of a federal government-backed biomedical translation fund.

- May 19, 2021: BiVACOR’s raises AUD$34m (US$22m) through a $US19m Series B funding round and a US$3m grant award.

- March 29, 2023: Raises AUD$28m (US$18m) in funding led by Cormorant Asset Management and OneVentures.

- 2024: July, BiVACOR puts its artificial heart into a Texas man for eight days before he receives a heart trasnplant.

Issue Seven of Forbes Australia is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.