Apple, GM, and Uber have abandoned their driverless dreams, and Tesla is under fire for its failures. But a Melbourne start-up, Applied EV, is still standing—and even turning a profit.

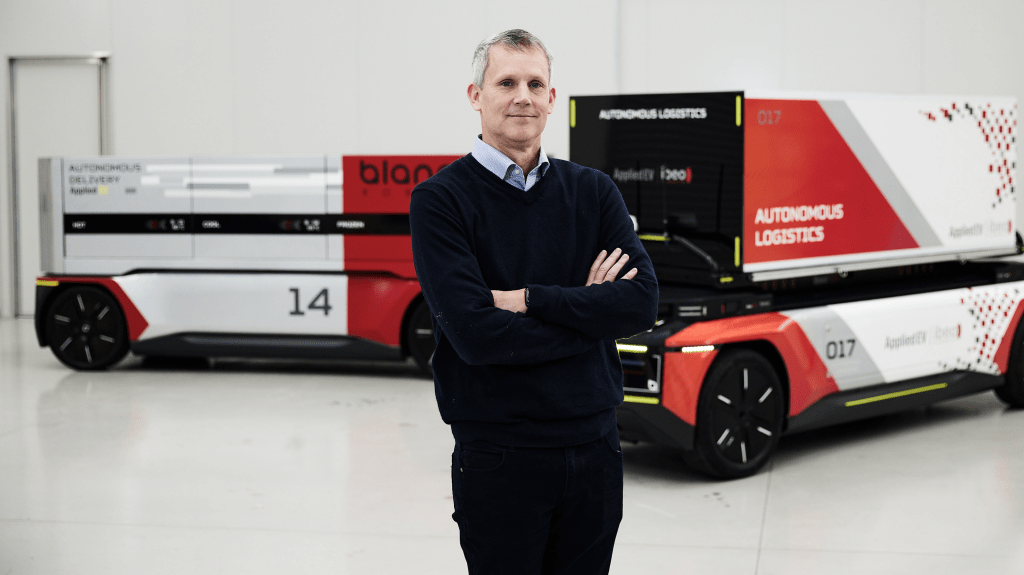

When Julian Broadbent and Shane Ambry founded Applied EV in a Melbourne garage in 2015, there were confident predictions that full self-driving cars would be on the road by 2020. But the autonomous EV industry has chewed up billions in investment with a junkyard of failed dreams to show for it.

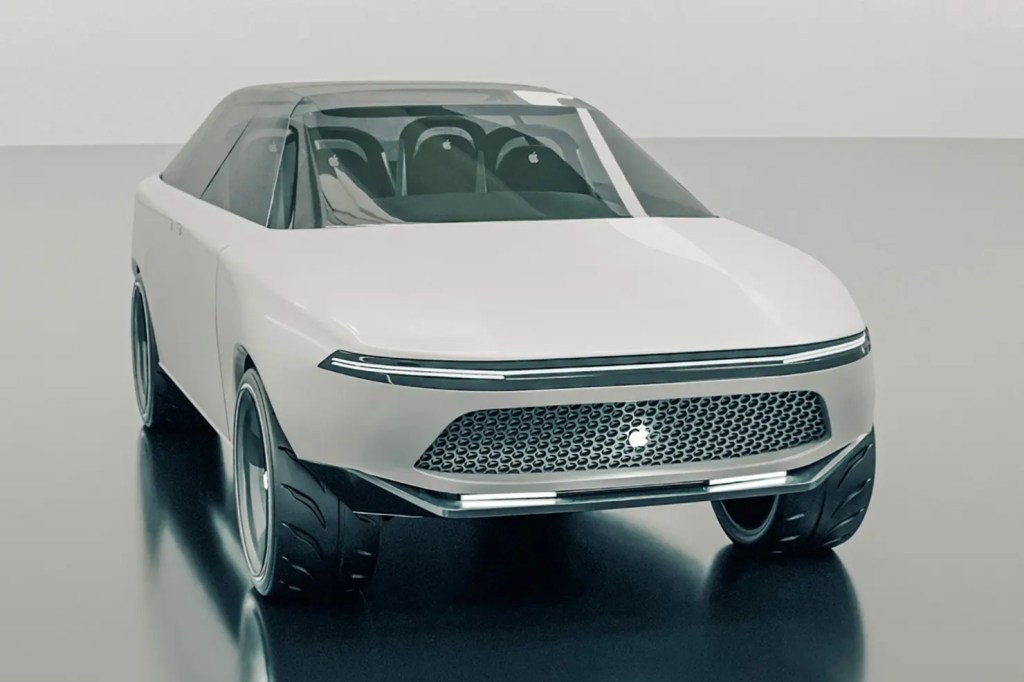

Apple shelved its Apple Car in February 2024 after investing hundreds of millions over a decade. GM pulled its Cruise in December 2024, after facing setbacks including an accident in San Francisco where a Cruise car dragged a pedestrian who had been thrown into its path.

Uber sold its self-driving division after a fatal accident in 2020 – a big call for a company whose long-awaited profitability depends on driverlessness. [It has since teamed up with the industry’s single big success, the Google-backed Waymo.]

Tesla has promised full self-driving since it was founded and has faced scrutiny and mockery following a string of safety fails, including killing a motorcyclist.

But Applied EV has 20 of its autonomous vehicles out in the world – with neither steering wheel nor driver’s seat – and says it is building 100 more, before going into full production. It announced on April 3 a partnership with UK-based self-driving software company Oxa through which companies can lease Applied EV’s vehicle platform equipped with “Oxa Driver” self-driving software.

In short, Applied EV has found a way to stay on track in an industry that’s been in permanent auto correct.

Co-founder Broadbent likens the current state of the industry to the washout after the dotcom crash of 2000. “We had that massive hype a while ago,” Broadbent tells Forbes Australia. “There were autonomous companies on every street corner, everyone was doing it, and now there’s a lot of carcasses around where maybe they didn’t get that quite figured out right.

“We’re left with the real guys that are going to deliver this, the ones that are understanding how it does fit in our world and how it does get commercialised.

“One of the objectives at Applied EV is to be part of the pending oligopoly. Like any industry, it’s going to become an oligopoly, and we know our role and we’re thinking very carefully about how we play our cards.”

So why did Applied EV survive while giants and minnows stumbled?

“In the early days, it was perceived that autonomous driving companies would do everything, and – credit to them – they took on all of the problems. We used to refer to that as boiling the ocean. Some of them wanted to build their own car. They wanted to be Tesla, Uber and a self-driving company all in one go.”

Applied EV’s strength, says Broadbent, was that it focussed on one thing: building the system that would connect company A’s autonomous driving software to company B’s vehicle.

It has entered into a partnership with Suzuki which is building the driverless vehicles. It’s in partnership with four [“soon to be five”] autonomous vehicle companies that create the autonomous “driver” – the part responsible for sensing the outside world, deciding where to go, when to brake, when to accelerate.

Applied EV’s role is to connect that “driver” to the vehicle with the Applied EV computer inside the vehicle, effectively being the foot that presses the non-existent pedals and the hands that turn the non-existent steering wheel.

Back in 2016, there were a lot of opportunities being put in front of them to take on different parts of the puzzle, says Broadbent. “But we always knew who we were as a business. We knew that we weren’t a Silicon Valley autonomous driving software company … we had a lot of conviction around the unmet need for vehicle-level compute that was safety-rated to do the jobs.”

And they steered clear of on-road in favour of industrial uses. “Any program in automotive would begin with a business case of 100,000 [on-road] vehicles.” But in the industrial and commercial sectors, some of the biggest companies in the world only had 1,000 vehicles. “So early volume for us is in the hundreds and thousands, not hundreds of thousands … that’s kind of where we’re thinking.”

Applied EV has 20 vehicles in use, says Broadbent who declines to name the companies – plural – using them. “What I can tell you is, partnering with Suzuki, we have got 100 vehicles now ready for final assembly. We’ve begun assembling some of those in Australia. We just launched the vehicle at CES [The Consumer Technology Association’s trade show in Los Vegas]. It has no cabin so it doesn’t even have room for occupants or a driver and we’re making it commercially available to customers that we can’t disclose at the moment in the industrial space.”

“We’ve got one customer which I can’t mention at the moment, they have a need for 3,000 autonomous vehicles for solar farms and large, broad-acre energy sites. That’s just one customer who can’t get people to do these jobs. In the world of automotive, 3,000 vehicles is small. In the world of autonomous vehicles, it’s huge. So, we find tremendous opportunity to create gravity and momentum by deploying vehicles at scale into these types of industries.”

Applied EV does intend to get into on-road vehicles but is in no rush, he says.

“We know there’s a tremendous market need for some on-road solutions. There’s declining populations around the world in some of the major markets. There’s driver shortages. There’s ageing populations in some industries.

“We know that businesses are becoming hamstrung either by the cost or shortage of drivers in the transport industry. So we really do feel great pressure to be on road, but we will take a step-by-step approach to begin to put vehicles on road in different parts of the world. But we find that there’s an immediate need for scale in some off-road opportunities.”

The company gets requests to help with large on-road trucks, Broadbent says, but is choosing to focus on last-mile delivery. “We also have requests for large buses and shuttles and things like that. But rather than spreading sideways, we’ve got this small vehicle that is ready to go. Suzuki can make as many as we want.

“They can make thousands at the right price. And we have a real business model. And I think we’ve found that the world doesn’t have that yet. The world doesn’t have access to tens of thousands of on-road autonomous vehicles. So we’re going to stay with that for a while.”

Applied EV has raised $40.5 million in capital and, over the 10-year life of the company, has made $74 million total revenue from engineering services, meaning Broadbent and Ambry have been able to fund the expansion out to 200 staff and still have majority ownership of the company with 26.1% each. Suzuki owns 4%.