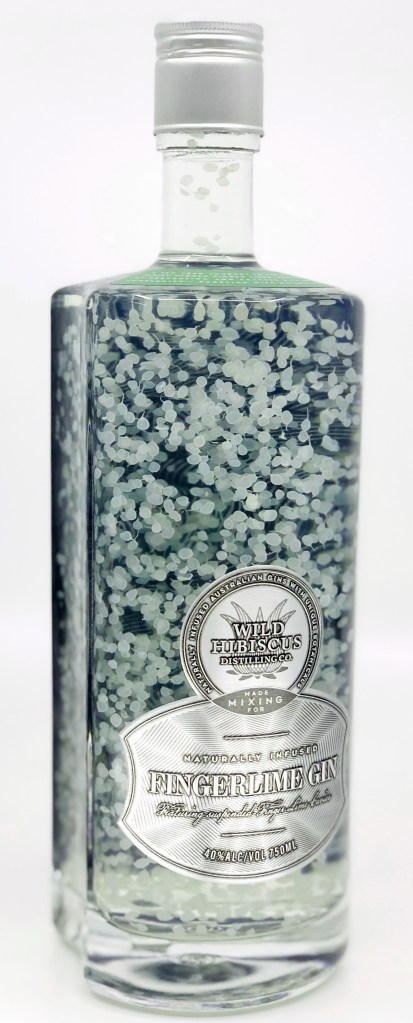

This is how Wild Hibiscus spent $1.6 million researching how to put ‘caviar’ in a bottle and create a magical spirit.

Lee Etherington’s journey to becoming the maker of finger lime gin began with a hibiscus flower dropped, on a whim, into a glass of champagne. The diners at his dinner party that night some 23 years ago watched as the deep-red flower – which he’d preserved in syrup himself – sank to the bottom … and then opened up.

They were all like, wow, that’s pretty cool. So he put another in and it, too, opened. Etherington was just out of university and running a little native-food tourism business on Sydney’s northwest outskirts. He started showing his customers his little trick and they universally loved it. He knew he was onto something.

The Wild Hibiscus company was born. It was an international sensation.

“People just loved it,” recalls Etherington. “We could never keep up with demand. You can’t just go to the market and buy a ton of hibiscus flowers, so I had to figure out how to grow them and where to grow them. Who could grow them for me. That led to the involvement with farming and vertical integration from growing things all the way through to marketing and export.”

He bought a farm at Kurrajong Heights, 70km northwest of Sydney where he’d grown up. He started employing growers in Thailand. And while working with these Thai growers he noticed a little blue flower – what he’d come to know as the butterfly pea – growing in the hibiscus plantations. It had the extraordinary property of creating a deep blue tea. But if you added lemon, lime or any acid to it, it turned bright pink.

“I saw the immediate application of that to cocktails,” says Etherington. “It’s a bit of magic and that’s what every cocktail bar wants. So I developed that blue flower and a lot of distillers wanted to make colour-change gins and vodkas, and wineries wanted to make blue or purple wine, so I was guiding them on how to use the flowers for their products and they were all very successful.”

The most well-known of these are Empress 1908 in Canada and Six Dogs in South Africa, and if you’ve seen a colour-change drink, you’ve probably seen Etherington’s flowers at work.

Having worked with a lot of drinks manufacturers, he got an urge to give it a go himself.

Back on the 35-hectare farm, he’d planted 1600 native finger limes, and wanted to add value to them. The first product was Gingle Bells, multi-coloured gin-filled baubles (pictured at top) to decorate a Christmas tree, then drink.

One of those gin flavours was finger lime, in which the plant’s “caviar” added a burst of natural citrus. Customers loved it and were asking for whole bottles of the stuff. But the problem was that when you put them in a 750ml bottle of finger lime gin, the “caviar” sank to the bottom, and no matter how hard you shook it, there were always too few in the first glass, and way too many in the last.

Etherington had studied environmental management at university and had taken a lot of biochemistry, with a particular interest in cell membranes. “It turns out that if you want to preserve food to last for years and taste like it was picked yesterday, it’s the cell membrane you need to preserve,” Etherington. “That’s how I can preserve hibiscus flowers for a five-year shelf life. And with the finger lime caviar, it’s key to the crunchy pop.”

He had a little laboratory on the farm and between all his other jobs, he’d lock himself in there and try to figure out how to suspend finger lime caviar in gin. There were traditional ways food manufacturers suspended things in liquid, but none of them worked with a 40% alcohol content.

And then there were the problems of the finger limes making the drink cloudy with bad flavours over time, and getting the caviar out of the finger limes, getting the alcohol into the caviar, and getting the caviar into the bottles without popping them. He had to develop entirely new systems for it all.

It took four years and $1.6 million of research – helped along by federal R&D tax incentives – to find the magic formula for suspending the caviar. And he’s not giving away the secret in a hurry. “The simple way to explain it is that it’s like there’s an invisible spider’s web within the gin. It’s fluid so it constantly breaks and reforms instantly. And the little balls of caviar get caught on the threads of spider web.”

The bulk of the bottle is a standard dry gin, but inside each of the caviar balls is a finger-lime gin, filled with citrus flavour.

Launched in December 2019 at $150 a bottle, the Wild Hibiscus Fingerlime Gin quickly sold out its 5000-bottle production runs. And while the hibiscus flowers are still the major part of the $5-million business which employs 15 people in Australia, 120 farmers in Thailand and 60 in Malaysia, the gins are growing.

“There’s nothing else like it, even remotely, anywhere else in the world,” Etherington says. “A normal gin distillery makes a batch in a few days. Our Fingerlime Gin takes us 18 months. Nine months to grow the fruit, and nine months to get the caviar out, run it though the process to convert the inside of each little ‘pop’ to 40% alcohol, and then to make the other gin that they’re suspended in.

“As you’re drinking the gin, you’re getting the little pops of the finger lime caviar. You can feel that hot burst and the different flavour.”

When he was developing it, he knew he was onto something. “But I had no idea how people were going to like it. You can sell something once, but you need to be able to sell it again and again to the same people – $150 is a lot of money for a bottle of gin. People would buy one, but then their second order was for a case, and I knew we were on a good thing.”