What is precision fermentation, and how did 200-odd dairy farmers come to own a start-up aiming to cut the cow out of dairy.

Jan Pacas, serial founder and vegetarian, was struggling to find anything he could eat while travelling in the US in 2019. On the flight home, he started researching the problem and read about the world’s relentless hunger for meat and dairy. He saw an opportunity – precision fermentation.

“As an entrepreneur, you ask big questions, so you create big answers,” says Pacas, who at that point had co-founded listed pet services company Mad Paws, plus two fintechs. In this case, his answer was to try to replicate dairy outside a cow with precision fermentation – the use of genetically modified microorganisms like yeast and bacteria to brew proteins (or fats) that exactly replicate, say, molecules in meat or milk. It’s the same process used to create insulin for diabetics since the 1970s and rennet for cheesemaking since Pfizer invented that process in 1990.

Pacas founded All G Foods at a time when plant-based producer Beyond Meat was scaling the Nasdaq highs of US$234 a share. Consumers, though, were less enthusiastic than the markets about fake meats made from soy and seed oils. Beyond Meat collapsed to barely US$7.45 a share at the time of publication.

But precision fermentation is not the same thing. Pacas and others are touting it as the way forward for the animal-food analogue business, and All G is one of a handful of Australian companies leading the way in the hope of bringing such technologically produced food to supermarket shelves and, in the process, creating a multi-billion-dollar industry while reducing carbon emissions and helping feed an ever-growing population.

US-based Impossible Foods began this new wave of precision fermentation in 2011 with its recreation of heme – the iron-containing molecule that makes red meat red – for its vegan Impossible Burger. Within a few years, a veritable incubator of start-ups followed, raising hundreds of millions to produce everything from eggs and collagen to plastic. Some, such as environmentalist Geroge Monbiot, have claimed that precision fermentation “may be the most important green technology ever.” And the buzz is sufficiently loud that Australia’s largest dairy co-operative, Norco, is a founding investor in another fake milk company.

But they’re all facing one big problem.

Who’s going to brew this stuff?

Michele Stansfield was running an almost 40-year-old agricultural biotech in regional NSW, Agritechnology, that was looking to dip its toes into the brave new world of precision fermentation. But nobody in Australia was doing the brewing.

With no brewer, there was no industry.

Stansfield contacted Phil Morle, a partner in the CSIRO-backed venture capital firm Main Sequence. She knew Morle was connected. She wanted him to introduce her to everyone in the precision-fermentation space. He went one better. In February 2022, he got all the players – government, research institutions, big companies, start-ups, her competitors – into the same room. “We all sat down and said, ‘We’re not leaving until we solve this problem,’” recalls Stansfield. “By the time we left, we’d decided that Agritechnology was the best company to move forward with this,” she recalls.

She took the idea to Agritechnology’s owner, David MacLennan, who she describes as a visionary who’d been “trying to find a way to feed the world with microbes since the 1970s”. But he was in his 80s and wasn’t prepared to take on the risk.

So, Stansfield went to Morle, and after a $10.5 million seed round led by Main Sequence in March 2023, she was able to buy Agritechnology’s assets from MacLennan (who died late last year) and founded a start-up, Cauldron, with the goal of becoming Australia’s precision-fermentation master brewer.

Cauldron will not brew exclusively for any company, says Stansfield, but will work with any company with the microbes to put in their vats. Multiple companies worldwide are doing this, but Stansfield wants to be first in Australia. “I think once we break ground and start building facilities, the others will come. And ultimately, I’m not concerned that we’re going to be out-competed because there’s such a huge requirement. We need 180 times what’s currently available by 2035 to keep up with the projected needs of precision fermentation.

“We need to build the whole beer brewing industry again, worldwide, to be able to keep up with people’s requirements for protein.”

Finding the fat, finding the flavour

Main Sequence’s Morle – a former theatre director who had been chief technology officer at file-sharing company Kazaa and co-founder of Asia Pacific’s first tech incubator, Pollenizer – was instrumental in setting up v2food, the meat-analogue company spun out of the CSIRO when the fake-meat industry was hitting its first consumer headwinds in 2020. v2food’s “meat” patty is made from soy and seed oil and was bumping into the problem of recreating animal flavours without the crucial animal fats.

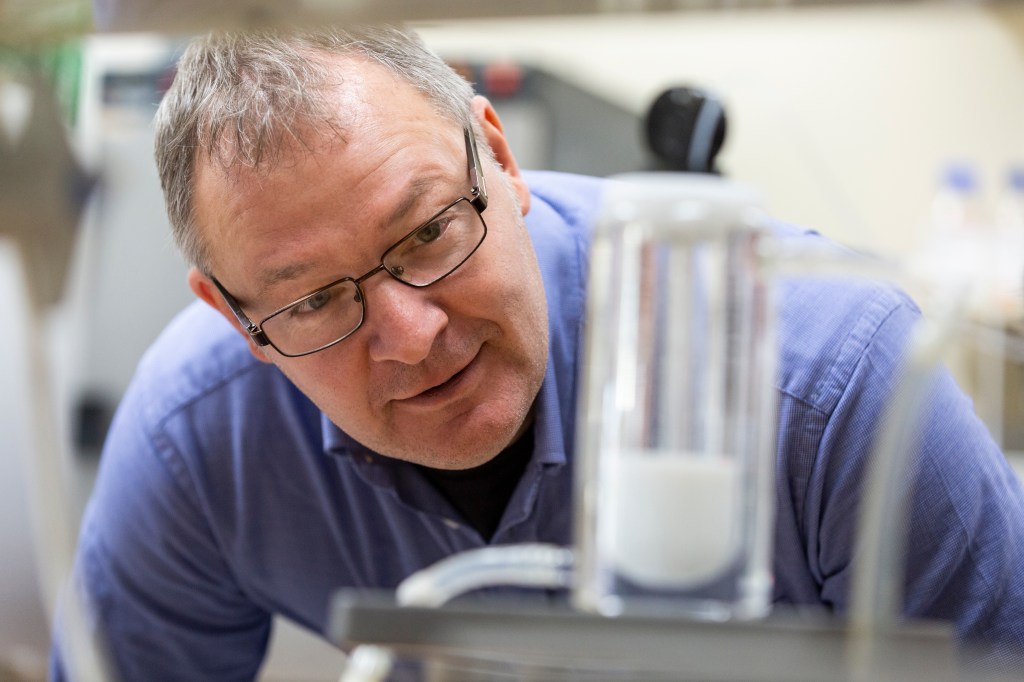

So Morle got behind former CSIRO scientists James Petrie and Ben Leita, whose start-up, Nourish Ingredients, was dedicated to replicating animal fats with precision fermentation.

Nourish put a lot of effort into studying which of the multitude of fats in dairy delivered the distinctive flavours and textures. “You can have a low-fat ice cream or a full-fat ice cream, and you immediately know the difference, right?” says Petrie, an avowed meat enthusiast. “There’s no fooling the senses. But how much of that can come from a plant source, and how much of it has to come from an animal? That’s the trick to this whole area because precision fermentation is expensive. You cannot afford to be producing fats that you can otherwise produce in a plant.” The actual amount of precision-fermented fat in Nourish’s final product will be small, he said – mostly short-chain fatty acids like butyrate and caproic acid – but they would have an outsized effect on taste and creamy mouthfeel.

Petrie offers a whiff of a vial in a hotel room in Sydney. “You can smell, but don’t eat it,” he says. The vial contains Nourish’s non-approved dairy-fat prototype, and, indeed, it has the sour notes of strong cheese (or old socks).

With the fat side of the taste equation covered, Morle wanted to create a company to make dairy proteins. “It’s a non-trivial challenge because there’s so many things to get right,” he says.

He pulled in the CSIRO’s director of Agriculture and Food, Jen Taylor, for the science and former Woolworths general manager of fresh food, Jim Fader, for the retail. They needed someone in the dairy business, so Fader contacted Michael Hampson, CEO of Australia’s largest dairy co-operative, Norco.

They had a “meeting of the minds”, says Hampson. “We both saw the value that we could create in this company and the value that Norco could bring to it.” That’s how Norco – a co-op owned by 200-plus dairy farmers – came to be the second largest shareholder of Eden Brew, a company that could appear hell-bent on destroying their industry.

Hampson says the reaction was mixed when he put it to his farmer-owners. “We had some saying, ‘This is an absolute masterstroke. There were others who were like, ‘I don’t know about this. What does all this mean?’ Then there are some rusted-on farmers. It wouldn’t matter if we made $100 million out of this; they’d still think it was a bad idea.”

This was a way for Norco to get into the 15% of the market currently choosing soy, almond and oat “milks”, Hampson says. “We can then create value for our members … We hold about 20% of the shares in Eden Brew. It’s got a post-money valuation of around $85 million [when it raised $25 million in 2023]. So we’re sitting there with a $17-million asset, and we haven’t had to put in a cent.”

The way it will work is that the precision-fermented “dairy” proteins will arrive at a Norco processing plant, probably dried. “We will take that and other ingredients and blend them, then run those down a bottling line,” he says. The first product would likely be a dairy-free ice cream. They are already in R&D trials using Eden Brew’s protein.

“We’re a 128-year-old organisation, so seeing the culture of a start-up and their sprint methodology, and getting that infected into our businesses was quite important because, as organisations evolve, they can slow down, and a slow organisation is not going to be a very innovative organisation.”

It’s all good

It was one thing for Jan Pacas to have the idea to make synthetic dairy proteins, but there were only a handful of scientists in the world capable of making that happen. Pacas had to find them and employ them.

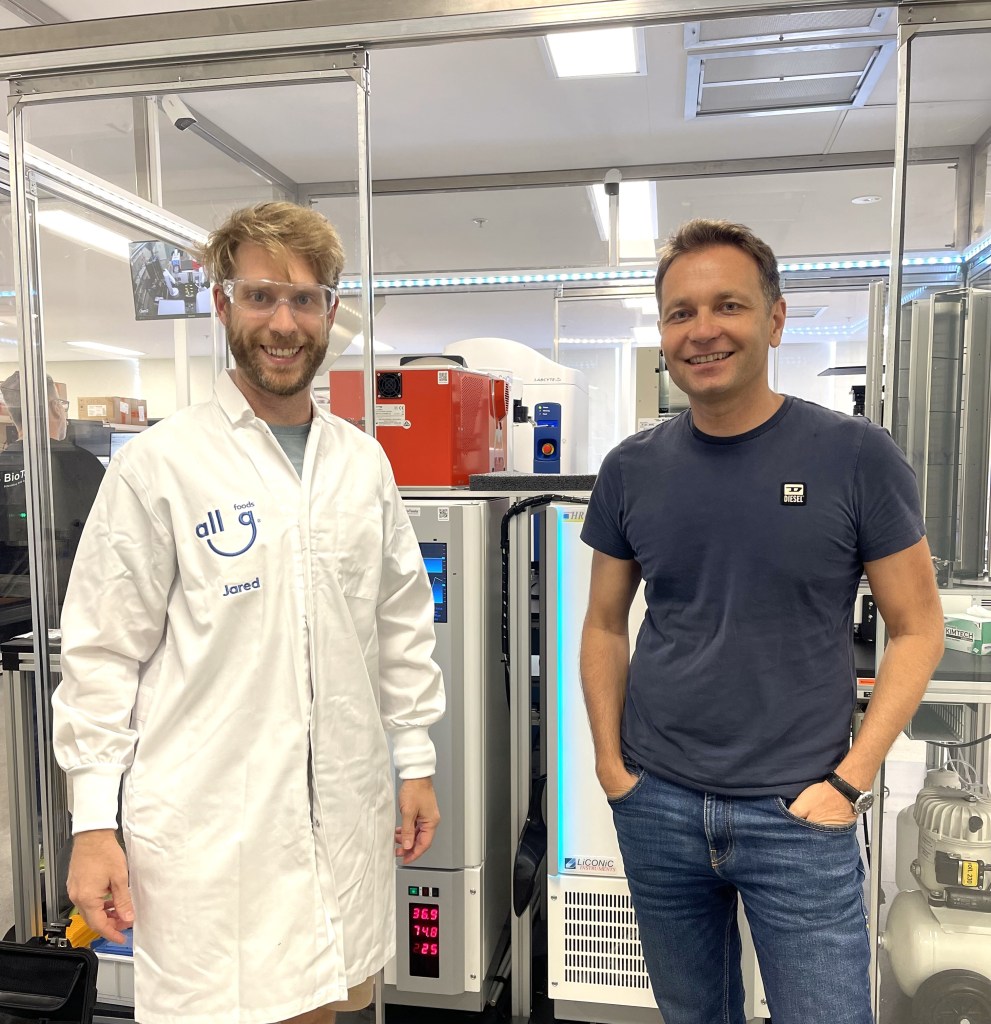

He started out with CSIRO food engineer Roman Buckow. “I rang him and convinced him to take his family and move from Melbourne to Sydney … Roman dropped the name of his colleague Jared Raynes but said Raynes would never move from Melbourne with a new baby.

Pacas googled Raynes and saw that the CSIRO biochemist and molecular biologist appeared to be the first in the world to have recreated the stable “micelle” structure of milk – in which the calcium and phosphorous are held in place with casein proteins in a form that is both stable and bioavailable to the human body. It’s the micelle that allows cheese to form and that keeps milk’s structure when frothed at high heat.

Pacas wanted Raynes. “As an entrepreneur, you never give up, right? I kept on hassling him and called him seven times while he was feeding his baby.”

While Raynes kept saying no, there was a chink in his armour. He’d been toiling at his research since 2013 but couldn’t get much interest from the CSIRO. Every year, he applied for a mass spectrometer, a necessary piece of kit, he thought, and every year he was denied. Every patent that had his name on it brought him zero benefit.

“What would it take you to move?” Pacas asked.

Raynes wanted to keep a hold of his inventions. “CSIRO owns everything you think about,” Raynes says. “I knew I had novel ideas and wanted to own them.” And his inventions might even get made – become food.

So he packed up the family and moved to Sydney, leaving his old IP behind but carrying a head full of new ideas. “I’d been thinking about how to do this properly for a very long time but just didn’t have the resources to execute my dream.”

They set about building a team of people who knew how to engineer microorganisms, flying in a team of 25 scientists with 18 different passports. Raynes had to teach them his casein knowledge so they could create microorganisms to brew up the desired dairy proteins.

The project was paid for with one of Australia’s largest seed funding rounds – $16 million in late 2021 – of which the federal government’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation contributed $5 million alongside Woolworths’ W23 venture capital fund and James Packer’s Ellerston capital. Pacas raised again in August 2022 with a $25 million Series A led by Agronomics, a UK-listed fund specialising in alternative proteins.

All G has now pivoted towards lactoferrin, a key ingredient in baby foods, some yoghurts, chewing gum and cosmetics, which has a role in activating immunity and carrying iron. “The price of lactoferrin is around US$1000 per kilogram,” says Raynes. “The worldwide production of lactoferrin is only around 500 tonnes per year. It’s a really good target for us, and we’re already significantly more efficient than the cow in making it.”

“Dairy milk is just incredibly nutritious, with multiple proteins, vitamins and other nutrients that aren’t replicated by a precision-fermented product, or crushed nuts, or crushed soybeans. The only similar thing is they might have a similar protein content, and they’re liquid, and they’re white.”

Jo Davey, food scientist

All G had bypassed Cauldron as a brewer because they were too far away from being in full production and gone to US brewer Liberation Labs instead, but All G was continuing to explore options with Cauldron. “Their progress was a bit slow for us. That’s why we’ve teamed up with Liberation Labs, who are building a 600,000-litre capacity plant in the US to be followed, most likely, by one in Australia.”

Liberation Labs is a good example of the difficulties of scaling this industry. CEO Mark Warner has said that it has raised US$51 million and is aiming for a US$75-million Series A raise just to build its first facility in Indiana. The US$115-million plant due on stream in the US this year will make between 600 tonnes and 1,200 tonnes of protein a year – only some of which will be All G’s product.

Australia’s 1.27 million dairy cows – essentially self-replicating, mobile fermentation vats that convert a cheap-as-chips input, grass, into milk – produced 8,129 million litres of milk last year, which works out to about 280,000 tonnes of pure protein.

It will be a long time before precision-fermented dairy is cheap and plentiful enough for precision-fermented milk bottles to be coming down the Norco production line. But Morle has done a thought experiment in which he estimates that if Australia’s entire $2-billion sugar crop was fermented into dairy fats and proteins, it would be worth $50 billion to $80 billion – around 14 to 22 times more than the value of the current sugar industry. The investment required to build that fermenting capacity would also likely be in the hundreds of billions. And then there’s the sugar supply issues.

Fats and proteins made with precision fermentation will enter the food chain via the highest-value products like nutraceuticals and trickle down into ice cream, coffee creamer, cheese and eventually into plant-based milks. Still, they would remain a minority ingredient in those products – added just for their crucial flavours and mouthfeel.

Note: Food Standards Australia New Zealand said it had not received applications from any of the companies mentioned in this story. However, each told Forbes Australia they were in discussions with FSANZ about regulatory approval and were hoping to be selling food by 2025.

But is it even milk?

“It’s not like milk. It actually is milk,” says Main Sequence’s Phil Morle of dairy made with precision fermention. But food technologist Jo Davey disagrees. “What is true is they can produce molecules identical to those in milk. So, they’ll produce beta-lactoglobulin, for example, the major whey protein in milk – exactly the same molecule – but that’s not all that milk is.”

Davey – a Food Standards Australia New Zealand board member and a director of Pirrama Consulting – has spent her career in dairy and learned about milk’s structure from isolating some of the high-value proteins for infant formula and other products.

And while precision fermentation can reproduce those high-value proteins, there’s a lot more to milk, she says. “For example, whey also contains alpha-lactalbumin, lactoperoxidase [an immune response enzyme], lactoferrin [which binds iron], immunoglobulins [aka antibodies]. There’s a whole lot of other proteins in whey which have functions for the consumer.”

Davey says the precision-fermented proteins will likely deliver the flavour and form of dairy products, but consumers should not be misled into thinking it is milk. “They can’t replicate milk because milk is a matrix of ingredients, so the actual structure of milk – the way it fits together – the protein-calcium matrix, and the other structures are all part of how milk is formed. Milk is a whole food, and we know there are benefits to humans eating whole foods and not just ingredients that are put together.”

The new products would have superior nutrition to current dairy alternatives, Davey said, but would not match cow’s milk. “From a nutritional perspective, dairy leaves the other products in the shade. Dairy milk is just incredibly nutritious, with multiple proteins, vitamins and other nutrients that aren’t replicated by a precision-fermented product, or crushed nuts, or crushed soybeans. The only similar thing is they might have a similar protein content, and they’re liquid, and they’re white.”

Not so Perfect Day

The pioneer in the world of precision-fermented dairy, US-based Perfect Day announced in January it had raised $90 million in a pre-series E funding round and its co-founders were stepping aside. Perfect Day was ahead of the pack in having numerous ice creams on the market. But it announced layoffs in August and withdrew from selling any product direct to consumers, instead focusing on business-to-business sales of its precision fermented whey protein.