How hard work and a sprinkle of fairy dust turned an idea into a $2.3-billion business within months.

Magic Eden founder Sid Zhang would like to thank the Victorian education system for landing him where he is today – a founder of the eighth-fastest company to reach a billion-dollar valuation.

Zhang couldn’t believe how little homework there was when he arrived in Melbourne in 2010. Aged 15 and living by himself – his parents were still in China – he had spare time that he wouldn’t have dreamed of having back in Guangzhou.

He picked up a guitar and tried to teach himself. Disaster! How about computer programming? Loved it. He still achieved a huge mark in the Victorian Certificate of Education. But when he chose a university course, the required mark for computer science was, you know, a little beneath him. So, finance and law it was. “It required 98.5 or something,” Zhang says. “‘Okay, this is worthy of me’.” He laughs at his own vanity.

Zhang emerged from university with a head full of money and jurisprudence and a job offer from Macquarie Capital, but he turned down the ‘millionaires factory’. “I’m like, ‘Whatever man. I’m going to do something on my own. I’m going to start a company’.”

In 2013, the fresh-minted Australian citizen left for Boston and started a cryptocurrency firm, Hello Block. His parents thought he was crazy, but he raised a small bucket of money, and he was away.

Back in Melbourne, Zhang’s good friend Jack Lu thought Zhang’s bold entrepreneurship was very cool. When Zhang invited Lu to work for him, the latter jumped on a plane. Like Mick Jagger and Keith Richards meeting on a train station and bonding over Chuck Berry records, the two budding entrepreneurs first met on a tram travelling to the same Box Hill maths tutor. They bonded over how hard the arithmetic was. (“Shout out to Dr He.”)

In Boston, Zhang had a lot of cool ideas: he dabbled in something akin to an NFT before they were even called that, and; he built a crypto wallet before that was a thing.

Don’t, however, suggest he’s a visionary. “Being early is the same as being wrong,” he says. Hello Block was a “dumpster fire”. The seed money was soon spent, and he knew he had proved his parents right. He had been crazy to turn down Macquarie. But he wasn’t going home.

Lu returned to Melbourne and a safe job with Boston Consulting Group (BCG), but Zhang stuck it out. Now in San Francisco, broke and homeless, he was couch surfing until the last friend whose couch he had been sleeping on broke up with his girlfriend. She kept the bedroom, the friend annexed the couch, and Zhang was on a windy Bay area street.

Another friend came through with an offer of staying on a 24-foot sailing boat moored on the bay. It was cold and damp and there was no power. He’d spend all day riding a borrowed bicycle and looking for work, then go to Starbucks to charge his laptop, phone and boat light. “I couldn’t afford a luxury like a drink, but the Starbucks staff let me sit. Thank you, Starbucks.”

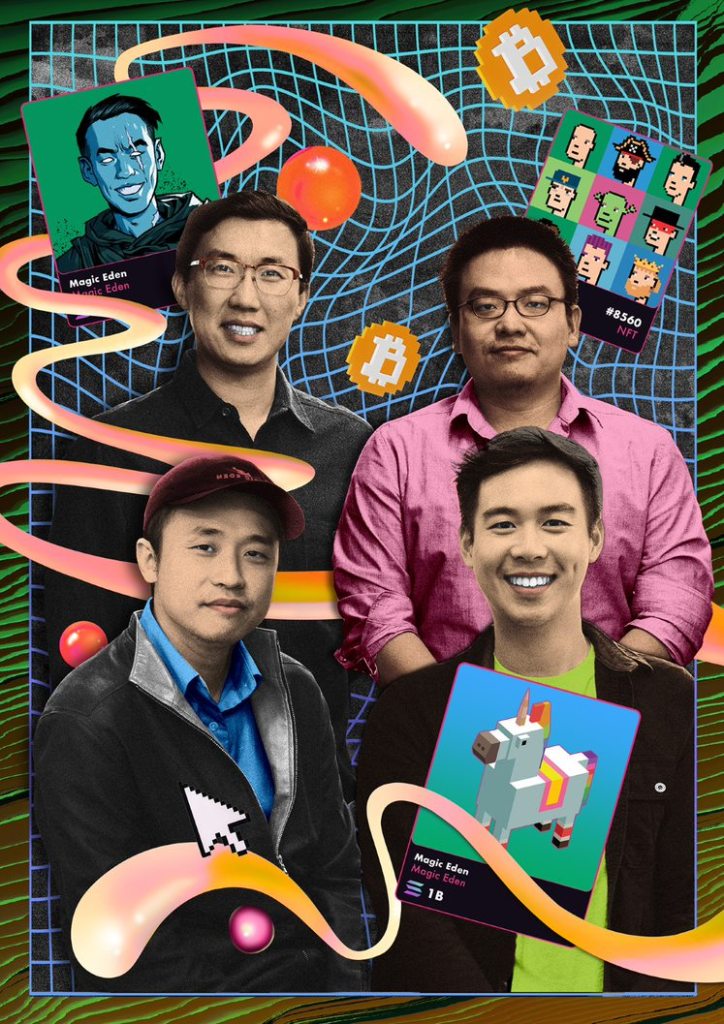

Zhang was at his lowest, and it would be a slow build to a fairy tale ending. For this is the story of how four guys born in China and Malaysia, came to Silicon Valley via Melbourne and Brisbane, and created a business called Magic Eden. Within nine months Magic Eden was the habitat of unicorns, with a valuation of US$1.6 billion ($2.6 billion).

Zhang eventually scored a job – at Uber – and was assigned to a team to figure out a way for the ride-share company to deliver food. “I started working on Uber Eats when it was a whiteboard … There were 15 people. We built that from nothing to [a business operating in] a few hundred cities.”

“Hey dude, I’m seeing a lot of crazy stuff in Hong Kong … Solana is really taking off and this NFT thing feels real.”

Magic Eden co-founder Jack Lu

Meanwhile, in Melbourne, Lu couldn’t get it out of his head that he’d seen the future. “I was like, how do I get back to Silicon Valley? How do I do something in crypto?”

A few years later, BCG sent him to San Francisco, and he never came home. He got a job with Google and worked on a product called Enhanced Conversions “which grew from zero to a few billion dollars of revenue”.

“At the end of that I felt I’d done everything I needed to do on my Silicon Valley pilgrimage: got to work with some of the world’s best engineers; got to work with Google; got to work on a cutting-edge product.”

Lu felt it was time to do something on his own in crypto. But what? He couldn’t think of anything in which he had a competitive edge. While he waited for an idea, he got a job with the ill-fated cryptocurrency exchange FTX and moved to Hong Kong.

FTX was a rising star, using a then little-known blockchain called Solana. “They had a lot of foresight that this [Solana] ecosystem could support applications not possible on the more popular blockchains like Ethereum,” Lu says. It might not have been obvious to the outside world, but “under the hood” he could see Solana revving up. Cryptocurrencies were skyrocketing in value and this new type of digital art, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), were being sold for outrageous sums on Ethereum – enough to make the front pages of venerable old media such as The New York Times.

At the beginning of September 2021, Lu connected with Zhang on Messenger. “Hey dude, I’m seeing a lot of crazy stuff in Hong Kong and Solana right now. Solana is really taking off and this NFT thing feels real. It feels like a mainstream-use case for cryptocurrency.” Lu had found his edge: building a seamless NFT marketplace on Solana where artists could launch their products and where everyday people could find them, buy them and resell them.

Zhang, still at Facebook and with the disaster of Hello Block eight years behind him, was itching to dive back in. In San Francisco, he and Lu had met and become friends with another Australian, Zhuoxun “Zedd” Yin. He was by now sharing a flat with Zhang, Zhang’s wife and their three-month-old baby.

When Yin tells people that he used to be in mining, they think he means Bitcoin mining. He has to explain: ‘No, like, big holes in the ground and hardhats with lights on them.’ His family moved to Brisbane from Malaysia when he was five. He did economics and finance at the University of Queensland and got a job with management consultants Bain and Co, finding himself in the mining niche, spending months at a time in the outback. Then Bain made the mistake of sending him to the US on a project. After six months, he told them he wasn’t coming home. “I arrived in 2015. The previous few years were kind of the golden years of big tech. The big social media companies … it was very exciting. I spent a couple of years working in startups … early-stage, 20-person companies. I figured out this was what I really enjoyed.”

In 2017, Yin started working with crypto exchanges, dYdX, and then Coinbase. “My job was to work with engineers and designers to create great user experiences. For Coinbase, it was to create trading products.”

Since then, Yin had been trying to convince Zhang to dive back into a crypto business, so when Zhang and Lu asked him to join them, he didn’t hesitate. They enlisted a fourth friend, Zhuojie “Rex” Zhou, a Chinese citizen, who’d been living in the US for 11 years and had worked with Zhang at Uber and Facebook.

They didn’t waste a day. They were ready and vowed to build the business in a month. But then they saw an announcement that another marketplace was about to launch, promising to be the “OpenSea” of Solana (OpenSea is the dominant NFT marketplace). They decided to jump the queue and launch in just eight days.

They all took a week off work in their regular jobs. Zhang and Zhou started coding while Lu and Yin created a white paper of all the things they hoped their site would be. Then they began tracking down every NFT creator in the world.

“The product was pretty shaky until day eight,” Zhang recalls. “That was supposed to be the launch. But there was some ecosystem outage and that gave us two more days to fix a bunch of things and then we launched.”

Yin: “It was a very intense, accommodating for Hong Kong, it would be late at night for us. I would go to sleep at 4am then wake up at 9am to accommodate US time then sleep 11am to 1pm then back to work again. It was insane.”

Why did they think they could do it?

“Arrogance!” laughs Zhang. “That was something we didn’t discuss. It was a mutual, implicit agreement.”

And this is where fairy dust gets sprinkled

By launch date they had less than 20 creators on board. Lu had set a target – “50 in five” – that they would have secured 50 creators within five days of launch. “Then we got 50 in, like, two days. ‘Wow! This is resonating.’ That was the first signal of product-market fit.”

The creators also had their own networks and brought customers with them. Within a few weeks, Magic Eden hit US$100,000 revenue a day. They had enough money to hire. Their first employee, Igor, lived in Croatia. Their second was an American nomad, a woman with no fixed address. There was no office; it was six people working from six addresses.

“We were small and paranoid,” recalls Zhou. “It’s crypto! We didn’t know how long the revenue was going to last. We decided to raise some money for a backstop.” A month after launching, they had secured US$2.5 million ($4 million) in seed capital.

The following month, November, the NFT market surged to an all-time high. Even so, they’d all been around crypto long enough to know the market could turn at any moment, or that a bigger, brighter way to sell NFTs might come along and blow them away.

They continued the remote employment policy and now doubt they would have survived otherwise. “We’re in San Francisco,” says Yin. “It’s one of the most competitive hiring markets there is … having no restrictions on location allowed us to get good people in the door really quickly.”

Says Zhang: “Talent is not geographical. That’s why we’ve got such a big Australian team (15) because Australian talent is just amazing. They also don’t have as many alternative places to go.”

While it creates a lot of complicated paperwork, they also have employees in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, Brazil, the UK, Germany and Vietnam.

The NFT market tanked on 2 May when Magic Eden was into its second capital raising, but the fall didn’t scare the investors. The company announced in June that it would raise US$130 million – valuing the company at US$1.6 billion, making it the eighth fastest billion-dollar valuation in history.

“It connotes a destination, something you can, like, be teleported to where things are unimaginable.”

Jack Lu, co-founder, Magic Eden

There was a day in April when Magic Eden turned over US$28 million on 411,700 transactions, according to the NFT tracking site, DappRadar. At the time of writing, Magic Eden’s daily turnover had plummeted US$25 million from that peak, but the number of customers had risen slightly and the number of transactions per day had increased by about 45% to 600,000.

Mercedes Bent, a partner at Lightspeed Ventures, one of Magic Eden’s investors, said she remained confident in the valuation. “Great teams persist through all times. The Magic Eden team is one of the most resilient. They adapted quickly, which resulted in them being able to continue growing key metrics like transaction activity despite the crypto downturn. We have the utmost confidence in their ability to navigate this environment and still feel they are a premium product.”

The capital raised means the company can disregard the market catastrophe and continue developing new products. It launched on Ethereum in August and announced on November 22 that it was integrating with the Ethereum-based platform Polygon which houses multiple games makers. It also says it intends to launch on more blockchains, while expanding into PFPs (pictures for proof), profile pictures and gaming.

“We want to build deep verticalized experiences,” says Yin. “We think gaming is going to be a key vertical so we’re investing heavily in that. We want to consolidate and unify a lot of the products to make it the best experience possible. We’ve been in crypto a long time. We’ve seen this pattern before. It doesn’t change the road map for us.”

The team eventually got an office, because that’s what companies do, but it sits mostly empty while the crew continue working remotely. “If ever you come to San Francisco, you can crash there,” Zhang offers.

They’re all still living in the same rented apartments, driving the same cars. Zhang’s still got his Kia. Yin doesn’t even own a car. Upgrading that stuff takes time. And while they might have suddenly become super wealthy, they are aware of the precariousness of all that. “It’s been crazy,” says Yin. “For anyone that starts a company this is the outcome you’re looking for, but I think we know this journey is a long one.”

They are saying their Zoom-meeting goodbyes when the question of their name comes up. Lu explains that a “startup name generator” spat out the moniker “Magic Den”. Somebody added the “E”. It aligned to the mood they wanted to create. “NFTs are like this new, alluring, almost mystical, thing – the future of art, of gaming, of community. It connotes a destination, something you can, like, be teleported to where things are unimaginable.”