As the countdown to Paris 2024 continues, Luke Trickett opens up on swimming’s lessons for becoming a serial founder – and subjugating his ego as he watched his more famous wife’s swimming career overtake his own.

When the Olympic swimming kicks off in Paris on July 27 the four children of multiple gold medalist Libby Trickett will be watching their mum commentate poolside while being minded at home by their father, Luke Trickett.

His wife’s glamorous trajectory was that which Trickett saw for himself when, on the junior team at the 2002 Oceania Swimming Championships, he won a bunch of races and was named swimmer of the meet. “It was really helpful for getting the attention of my now wife,” he says.

The then Libby Lenton only got a minor medal at that meet, but their relationship began and, two years later, the tables had turned. Luke Trickett narrowly missed the Athens Olympic team while his girlfriend became a gold medalist and world record holder.

Trickett kept swimming. At the Australian Championships in 2008 he swam a personal best but again narrowly missed the Olympic team. With a torn ligament in his shoulder and an aching body, he knew it was over. His new wife, however, went off to Beijing and brought back a bagful of gold. “It was this real period of reflection for me, a tearing down of the ego,” says Trickett, “as I took more a supporting position to Lib. Being an athlete is quite egoic. You need to be able to feel like you’re going to do the job. Everything kind of just got turned upside down for me.”

“You have to take the tiny steps every single day. As unglamorous, unsexy as they are, you’ve got to take them when no one’s watching, when no one cares.”

Luke Trickett CEO and founder of Blue Stamp

Trickett had been training 30 hours a week while working as a stockbroker. At 25, he felt old. The Global Financial Crisis was in full swing. The markets were roiling.

“You’d wake up, and the markets were down significantly because there’d been some big event. And you would see these stable businesses with good customers, strong financial position, a lot of cash, and they’d just get slammed by investors responding to big headlines and emotional, psychological events.”

He saw an opportunity.

The couple had bought a home and an investment property. They sold them both to invest. Among other small caps, he bought Nick Scali at 49c and IT consulting group DWS Advanced Systems. As the stock market continued its seemingly never-ending plunge, Luke Trickett decided to leave broking to set up his own fund, Blue Stamp. But in doing that, he had to recognise his weaknesses.

“It was a real intense moment in our lives where, I was leaving swimming, I left broking, we sold our houses and put all the money in the stock market when the market was just collapsing. And Lib went to the Olympics and won three gold medals. It was a wild time,” he said.

“I’d been a terrible broker. I did not want to get on the phones. I did not want to talk to anyone. I was just interested in researching these businesses. It was good to spend that time around the analysts, but in my 18 months doing it, I executed two orders. That’s a bad day for one broker. I’m not a salesperson.

“I just thought, ‘I’ll set this fund up, and then I can just sit in an office all by myself and just comb through financial statements and find great businesses to own. What I didn’t realise is, ‘Oh, you still have to sell yourself. You have to go out there and promote what you’re doing and get people to invest in the funds.

“All I wanted to do was let my performance do the talking. As an athlete, that’s the law of the universe. You deliver results if you want to progress. It’s brutally objective, and it’s down to just you. You can’t rely on someone else to get you there.

“With investing, you can do years of work on a company, and then you have the opportunity to invest in it, and that’s when you get to realise the value of all of your analysis. And hopefully all that work separates you from everyone else. I love that.

“Sitting in an office by yourself is really not too dissimilar to going up and down a pool for three hours a day … There’s a lot of similarities in being an elite-level swimmer and a high-performing individual in an organisation. “The constant battering of your body becomes a constant smashing of your mind as you try to work through problems.”

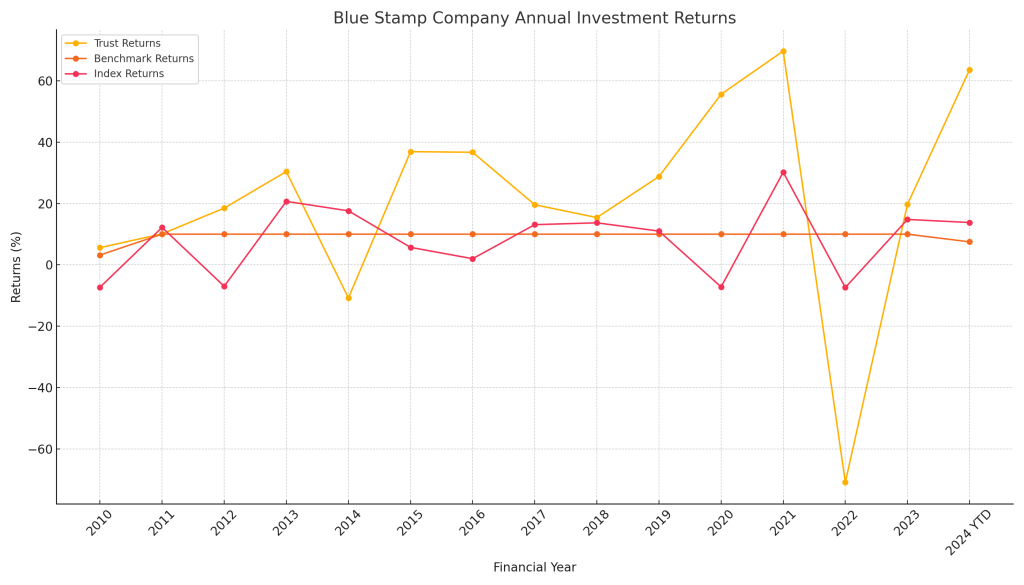

Trickett got the performance – better than 20% average annual returns after fees, he says, of those early years – but the investors didn’t come flooding in. “You have to take that investment performance out to the real world and market it. And I didn’t want to do that. I was like, ‘Great Luke, you might not like selling, but actually, if you want to turn this into a business, you have to sell, mate,’ so that’s the kind of realization that I had to accept and start to operationalize.

“It was a hard slog. I started the fund with $80,000 … ridiculously small. It took 45 months to get to $1 million, and 25 months to get to $2 million. You don’t get to a scale that can support a business until it gets to about $20 million, so it was a hard, hard six years because my focus was on investing, not on self-promotion. I really paid for that.

Money for jam

It took eight years for the business to become fully self sustaining. And through those years of financial struggle – relying on his wife’s income to make ends meet – a new idea arrived.

“Lib was out with her girlfriends for lunch during the dark years, so to speak, and it was her turn to pay, and there wasn’t enough money in the account. It was incredibly embarrassing for her.”

Luke Trickett

“Because Blue Stamp was so small, we were solely reliant on her income to be able to go and buy our groceries and pay our mortgage. The challenge is, her income is very lumpy. She might get paid once every three months. Her customers are large corporates, and they pay whenever they want to pay. Unfortunately, mortgage payments don’t shape themselves around when you get paid. It was a brutal time for us where we were reliant on loans from my parents, my brother. We had about six credit cards on the go cycling balance transfers to be able to manage that. We needed these invoices to just be paid.

“So it was this analysis that I’ve done on companies in the space, combined with this lived experience of late invoice payments … that teased out this opportunity for a business that I started in 2019 called Marmalade. It was an invoice payment service to assist small and medium-sized businesses manage their cash flow without getting into debt.”

Trickett had no idea how to set up such a business. “Maybe this is a reflection on me. But it literally takes me years to work it out. You’re constantly adjusting and reshaping and repositioning for the business and bringing on new people, investors, whatever it might be to get you to the next incremental steps. Trickett co-founded the company with two former Afterpay employees, Richard Johnson and David Whiteman. Marmalade raised $17.9 million, finalised in April 2024.

“You might have a grand idea, but it has to be broken down into small, manageable steps that you can take on a daily basis that will get you there. It’s exactly like being an athlete. You want to go to the Olympics, that’s great, but you actually have to take the tiny steps every single day, as unglamorous, unsexy as they are, you got to take them when no one’s watching, when no one cares.”

Out of those tight financial times came another idea.

“Lib was out with her girlfriends for lunch during the dark years, so to speak, and it was her turn to pay, and there wasn’t enough money in the account. It was incredibly embarrassing for her.” But her husband saw a problem to be solved.

Afterpay was going through the roof in the post COVID-19 market boom, reshaping the world of point-of-sale credit. “It gave me the idea that instead of Lib paying for the whole group’s purchase, why couldn’t she just pay for her share and have a payment service that settles the rest, then she receives a link to forward to her mates for them to settle their share later.”

That was how the latest venture, Backpocket, began in July 2020, although it is finding its real-world application more in ticketing and experience providers, Trickett says. “Say you want to go to the Taylor Swift concert with three mates. The tickets are $100 each. Instead of paying $400 at the point of sale, you check out with Backpocket. The organizer pays for one ticket for themselves and we settle the $400. They receive all the tickets and they share the link with their mates to settle up. We’ve seen the live events industry really benefit from it and other experience providers, like Paint and Sip. We have florists, sports equipment providers.”

“They look like different things – swimming, Blue Stamp, Marmalade and Backpocket – but I look at them as all one endeavour, which is trying to bring new value to the world.”

With Blue Stamp now up towards $50 million under management and the start-ups taking off, he’ll still be at their Brisbane home with the kids watching Libby poolside in Paris, the first Olympics she’s been to since retiring from the pool after the London games. Their three girls and a boy, ranged from 8 to 1, have inherited at least some of their parents’ drive. “They’re raw competitors,” says Luke. “They’re hyper competitive. I don’t know if that’s a good thing. We try not to pour fuel on that fire. Any time an Australian’s competing – doesn’t matter if it’s swimming or badminton – they want to stay up and watch.”

Are you – or is someone you know -creating the next Afterpay or Canva? Nominations are open for Forbes Australia’s first 30 under 30 list. Entries close midnight, July 31, 2024.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up for the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.