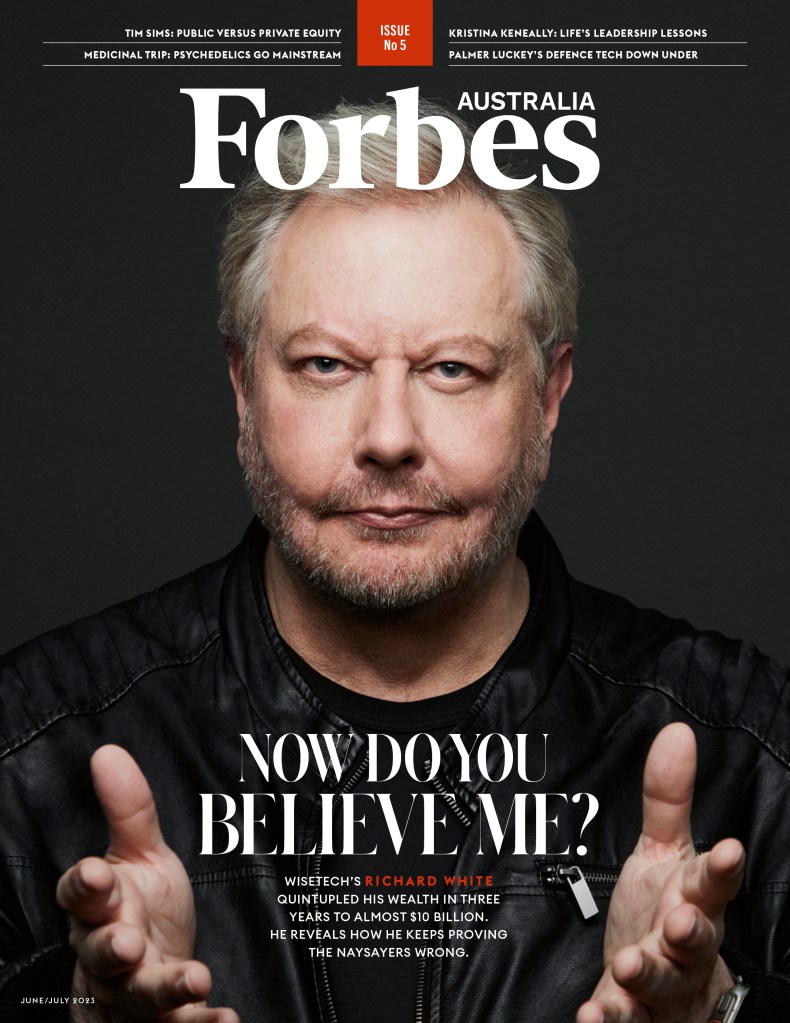

RICHARD WHITE is gobbling up the world of freight software with a personal fortune that has more than doubled in the past 12 months to more than $10 billion. He tells how he went from refrigeration mechanic to Australia’s seventh richest person.

Over a glass of wine two relatively unknown geeks were discussing their payment models, software-guy-to-software-guy, after a tech function in 2007. WiseTech founder Richard White tells Atlassian co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes that he charges the full fee upfront for his transport logistics software, then 20% annually for maintenance.

The trouble is, the customer always pushes back hard against the upfront fee – up to $1 million – attacking it in negotiations so that White needs to expend time and good vibes defending it. He tells Cannon-Brookes that he holds the line on the maintenance fee but always takes a haircut upfront.

Cannon-Brookes – who at the time was valued at $26 million – pipes up that he charges less upfront but has a 50% maintenance fee. It gets White thinking. He is a student of the Theory of Constraints, which focuses on understanding bottlenecks and how to deal with them.

“Why don’t we take it to the extreme?” White recalls thinking. “Why don’t we charge zero for the software and 100% for the fees?” The term “software as a service” [SaaS] is still four years away from being coined, and while the actual model might have been invented a few years earlier, White hasn’t heard of it – nor has his American vice president of sales. “He loved big sales and big upfront fees,” says White. “In a board meeting, I announced the new model, which we called On Demand Periodic Licencing. [The sales VP] said, ‘This is terrible. No one will stay because they’ve got no skin in the game. You’re going to destroy the company. I want to sell my shares.’ To his credit, Charles [Gibbon, chairman of the board] said: ‘How much?’ And we bought him out.”

The new payment model was launched in 2008 as the global financial crises began to bite. “By the end of 2008, there was not a single capital budget left in any major company,” says White. “You only had OpEx [operational expenditure]. We had a no-upfront-cost model. We literally grew at 3% a month from 2008 to 2011. We would have lost a huge amount of sales on the capital model. It was the best thing I ever did.”

The huge growth, however, created a new bottleneck. White now had a backlog of more than 100 major installations. Again, White needed to find a solution. Again, he was told the answer he came up with would ruin the company, and again he ignored that advice.

It is a pattern that recurs in the unlikely career of Australia’s 7th richest person – from refrigeration mechanic to rock guitarist, guitar repairer to computer guy – Richard White’s software now dominates the freight world, giving him a clip from half the containers shooting around the planet. While his old friend Cannon-Brookes has gone on to be Australia’s sixth richest person according to Forbes’ 50 Richest, the high-flying Atlassian has more than halved in value since its high of last August. WiseTech, meanwhile, doubled in value between June 2022 and May this year, giving White – who owns 39.72% of the $25-billion company – a personal fortune of more than $10 billion, propelling him from 10th to 7th, past Westfield’s Frank Lowy, and Canva’s Melanie Perkins and Cliff Obrecht on the Forbes list, in just the last five months.

The Boy from Bexley

White, 68, still lives on the property where he grew up in the unassuming inner southern Sydney suburb of Bexley. His grandfather had bought an old home in the 1940s and turned it into a ballroom. White grew up in a weatherboard house out the back and used to run the giant dishwasher for wedding receptions from age 12.

“I remember feeling so engaged. I had people depending on me. Every Friday, my grandparents would ceremoniously give me my pay packet, a little brown envelope. I’d feel this enormous sense of achievement. I can’t remember how much money it was and have no recollection of what I did with it. What was important was the reward. Effort, engagement, achievement, reward. I’m sure they did it ceremoniously to instil that feeling.”

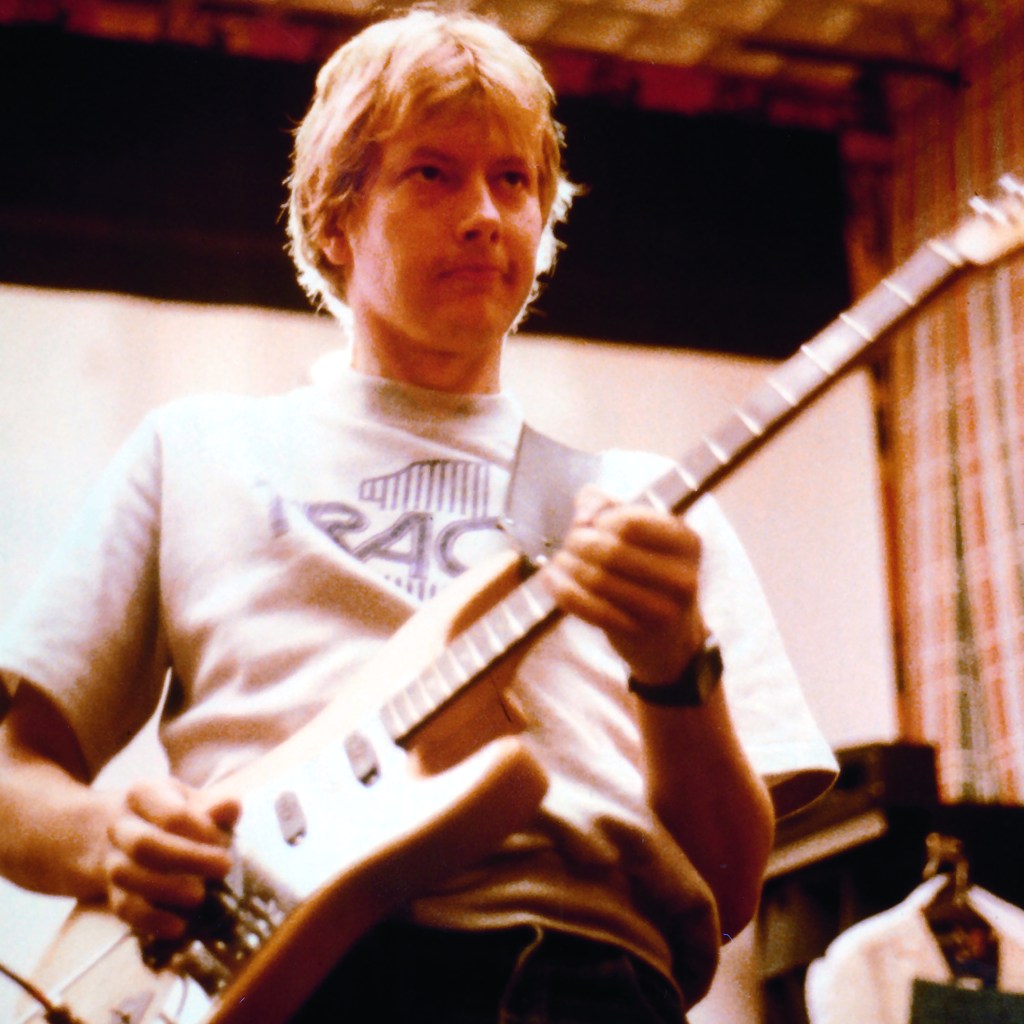

His parents also had an entrepreneurial bent. His father ran an engineering business, and his mother sold cookware through the house-party model. His mother encouraged him to learn music and to read. She was always slipping him science fiction books. Around 17, he found the guitar via ukelele and started playing in bands.

“My father was a strong character. He didn’t like musicians at all. In his words, ‘They’re all deadbeats.’” His dad said he could play in bands so long as he got a refrigeration ticket. It was dirty work, “crawling around in roof spaces, dust and grime. I’d turn up sleepy because I’d been out playing till 3 am at Chequers. I wasn’t the greatest employee.”

He quit the band and his job to focus on his guitar repair business. But in his spare time, he started building winch-up lighting stands for the entertainment industry in his father’s workshop. It soon morphed into a factory employing 20 people. In 1982, he merged the business with an entertainment electronics company, Jands, that continues today. “I’m an R&D manager, and I don’t have a degree.

I have five engineers working for me who all have degrees. I was the creative. I could imagine things.” White stops telling the story to cast a picture of a computer lighting board from his laptop to his loungeroom’s giant screen. “[For] my first project… I laid out all the circuit boards myself, and I had to program the computer.” Why didn’t he employ someone to program it?

“I don’t think I knew anybody who knew how to program.”

He’d taught himself. He’d started fiddling with a Tandy TRS80 in about 1979. By the time he got to Jands, he was already aware computers could control lights. “I just didn’t have a playground to do it in. I bought a bunch of books. I’d stay after work, go in on weekends, and start doing the work. I practised incessantly and became fluent in it. It was intense study and application.”

“I became known as “The Doctor” because I could fix a computer quickly.”

Richard White

Reg Kennedy, his flatmate at the time, recalls White got up early and worked late. “Just always doing things; reading computer books, using EPROMs (erasable programmable read-only memory), mucking around with modems. They were called acoustic couplers then.”

White says that if he doesn’t understand something, he feels the need to dive in and get his head around it. “As long as you’re not afraid of failure, you’ll pick things up quickly. Perfection is not a great goal.”

After the light controller, he installed Jands’ first PC network. “I became known as “The Doctor” because I could fix a computer quickly.” He learned an important lesson from the company accountant, who said he didn’t need a computer – until White demonstrated what it could do.

White sold out of Jands in the mid-1980s and bought a computer retailer, Clear Technology, but found the low-margin, high-volume model unsatisfying. He sold and set himself up consulting on systems integration. He landed a few freight- forwarding clients and realised they had terrible systems. “They had computers, but they were only using parts of them, and they were not integrating them. There was no through process, no holistic system.”

Burdened with crippling interest rates on his Newtown home mortgage in 1990, he took a job in southern California on another freight fulfilment system which had the same problems, and when he came back in late 1991, he’d seen a solution. He locked himself in his bedroom and started writing the freight forwarding program he hoped would change everything. The company was renamed Eagle Developments International (EDI). The new product, Deliverance, was “an unfortunate reference to an old movie”.

“It was a strong product. It had all the components in it. It worked perfectly for a lot of small to mid-companies.” He started buying other small companies to incorporate their technology, and EDI grew to be the big fish in the Australian freight-software pond.

In 2000 he found himself doing a masters in IT management. He made sure all his assignments were on his own business. “I’d turn up at work, and my staff would look at me with horror, ‘What’s he going to do now?’ In 2002, I told the marketing manager, ‘You run the business. I’ll talk to you a couple of hours a week, but I’m building a new system, and it’s going to be global.’ I hired 16 new people and told them not to talk to the others. ‘This is the new company. This is what we’re going to build, and this is how we’re going to build it.’”

The new system needed to incorporate different corporate entities across multiple transactions in multiple countries with different customs and accounting controls. From booking a ship in Antwerp through customs clearance and invoicing when a container arrived in Wagga Wagga, it was all going to be in the one system. The little pond was getting too small for White’s big fish.

“I’d spent 10 years thinking about it, and a master’s degree allowed me to flesh it out and put some management thinking into it. I remember when I was building the system, I’d have customers come by, and I’d tell them what I was doing, and they’d say, ‘Why are you doing that? We don’t want that.’ But I was convinced it was going to be much better. When I released it and showed it working, they were like, ‘Ah! Now I get it’.”

Until this time, EDI had made six acquisitions, including in Singapore and New Zealand. There were no integrated international freight software systems because every country had different, complicated customs rules. EDI started on the problem, one country at a time.

In June 2005, turnover was still a modest $10.6 million. White had spent the money he’d saved in the 90s and sold his house to build the new international product. Now, if he was going to take it global, he needed outside money for the first time.

Merchant banker Charles Gibbon recalls there were “other people hunting” to get in on EDI. It was already dominant in Australia, employed 100 people with plenty of cash flow, so it was “very much on the path”. But it was White’s enormous depth of knowledge that convinced Gibbon.

“A good word is the German word gestalt, where you’ve got the whole and the parts. He fits into that category. He always showed an ability to be a visionary and yet always be across the detail, whether it be programming, security, psychometric testing for staff, sales initiatives, structuring, whatever it was.”

White recalls that Gibbon put in $2.5 million. (He now holds 5.2% of WiseTech Global Ltd, which values Gibbon’s holding at around $1 billion.) “I didn’t have it all my own way,” Gibbon says. “Venture capital in those days was pretty brutal. Looking back, I had the good sense to structure a more user-friendly deal than the industry was doing.”

Mike Gregg – then managing director of Health Communication Network and now a founding partner with Gibbon at Shearwater Capital – was the other major investor who came in with “slightly less”. Armed with the new capital, in 2006, EDI bought a Chicago-based company with a domestic forwarding product called CargoWise. “I loved the name,” recalls White. “It was hard to be an Australian software company in America in those days. We just weren’t on the map.” So, they renamed the global company CargoWise EDI and left the press release intentionally vague about who bought whom. “The Americans just assumed it was them who bought us.” That year, they also moved into the UK.

With business exploding after adopting the SaaS model in 2008, the 27 trainers who implemented new systems around the world could not keep up. And the cost of training was always a point of contention with new customers. “Using the Theory of Constraints, I decided that the solution to how to scale the company’s training resources was not to do it at all. The solution was to create a powerful set of content libraries that allow the customers to self-train.

They can’t complain about the cost because they can do it for free. It’s all there. I took about three of the 27 trainers to build that new content. My training manager, Tanya, freaked out: ‘It’ll destroy the company. We’ll all be killed.’”

They started certifying outside “partners” for free so new customers could pay someone else to train them, but it had nothing to do with WiseTech. They dropped $5 million in training revenue, White says, “but picked it all up in accelerated sales”.

So pervasive has the culture become of not wasting employee time explaining things even company director Gibbon gets told, “go to content” if he ever wants to learn how something works. As a shareholder, he thinks it’s great. “It allows the company to scale and scale quickly.”

In 2014, with an updated generation of products going gangbusters, and a new name, WiseTech Global (because too many people thought CargoWise was a freight company), the new entity started preparing to go public. About a third of the 450-odd staff owned shares, so an IPO would give them a harder, liquid value.

White, Gibbon and Gregg thought a fair price would be $3.35 a share. “The investment banks are your best friends during the listing process, up until the day of the book build,” says White.

“These are people who you trust and who have given you a lot of great advice, and suddenly on the day of the book build, they turn out to be your nemesis. They say, ‘You’re never going to get that price. You’ll have to lower it.’ They turn into advocates for the hedge funds.”

White describes a sales act where the investment bank negotiators said it would be a “broke listing”. When he didn’t budge, they got their managers to repeat the line, then their managing directors. “This was performance art. I said, ‘List us, don’t list us. It’s up to you. All I can tell you is that fortune favours the brave. You choose.’”

They listed, and WiseTech closed on day one at $3.89. Seven years later, this April, it passed $67.00 – 20 times the IPO.

How does it feel to find yourself so wealthy?

“I never thought of this as personal wealth,” says White. “I thought about it as a measurement of achievement. You can’t reconcile in your mind having this sort of money. It’s beyond normal logic. But if you think about it as what you can do with the money and how you can help other people, what I’ve done for shareholders, that’s very powerful thinking.”

He thinks about his Aunt Wendy in Perth, who he got on the chairman’s list before the IPO and who has been able to put her grandchildren through university with the proceeds. “I’ve had lots of shareholders come to me and say profoundly wonderful things about what it’s meant for them. That’s a great feeling.”

Before the IPO, WiseTech began a strategy of buying small overseas software companies that did customs clearance, notably in China, various European countries, South Africa and Canada. They weren’t buying them for their customers or their revenue, says Richard White. “We were buying people and knowledge.” They needed staff on the ground familiar with the complexities of local customs laws. The plan was that once established, the full suite of CargoWise products could be rolled out there.

The strategy picked up pace, and in the four years from 2017, a further 39 companies were gobbled up.

“These are small, founder-led tech companies, so the DNA is similar to ours,” says White. “We’ve built a lot of new technology using their skillsets, and we’ve made many of them very wealthy.”

But the cost of the acquisitions made WiseTech’s cash position look uncertain. Rapid acquisitions, meteoric growth – the market had seen it all before.

White was in the office on the morning of October 17, 2019, when the investor manager called him over: “There’s a crisis.” People were sending her copies of a report by short-seller J Capital accusing WiseTech of using accounting wizardry to inflate growth and overstate profits. White recalls her saying it was the end of the world. “I looked out the window and said, ‘The sun is still shining.’”

Shares fell 10%. “Our job was to suspend trading in the company to correct the misinformation. It’s not a small thing. Long hours. They’d spent six months researching this, and we had 24 hours to respond.”

More short reports followed. The last was in February 2020, when COVID-19 was a new unknown. White was among the first business leaders to say this thing was real. He had the shipping numbers and needed to inform the market that trade flows out of China had collapsed 90% – as would his revenue. The short sellers saw it as an excuse. J Capital called its last report “Covid Ate My Homework”, as the WiseTech share price tumbled 27% a day ahead of the rest of the market. White maintains that the intention all along was to back off the buying spree and start consolidating the purchases.

Over the following 12 months, as people stuck at home started spending and world freight became overloaded, WiseTech’s cash “went through the roof”.

“You invest, build the business, build the software, win new customers. It’s a complex set of efforts, and having done all of that, you then have a position where you can say, “Now do you believe me?”

His grandparents had sold the family property, but he repurchased it in 2014. He kept the historic façade of the grand old house and gutted the interior. He converted it all to solar with a massive Tesla battery in the basement, where he also built a music studio with the largest mixing desk on the market. “Now I can afford to be a musician,” he jokes while showing it off, adding that the Angels’ Brewster brothers, John and Rick, had been rehearsing there the previous week.

He demolished the weatherboard house he grew up in out the back and built six townhouses. Reg Kennedy lives in one and works as a gopher. He installed his Mum in the California bungalow next door.

“As long as you’re not afraid of failure, you’ll pick things up quickly. Perfection is not a great goal.”

Richard White

His old bandmate Tony Jex had stayed in the music industry as a manager, but when Covid hit, he lost all his business. White asked him to come and manage the music studio. They don’t see a lot of each other. White always seems to be away, says Jex. But when Jex told White he’d been to a recent Jason Bonham concert at the Enmore Theatre, White had been there too. But Jex had been up in the VIP area while the billionaire was down on the floor.

White says he has no intention of slowing down. He might have broken a suburb record – $27.5 million – for a beach house at Palm Beach on Sydney’s northern peninsula, and he might have bought a country home in the hinterland above Berry, south of Sydney, with Teslas in the garage, but he’s still too busy to see much of them.

“It feels like it’s fun. Not every single day is fun. There are all sorts of tough things you have to do. The short attacks were not great. The initial shock of COVID was profound, but you’re strengthened by the tenacity to get through them. I’m pretty resilient, but I also really like the intellectual effort of applying yourself to something, diving in deep and making it happen.”

White says he’s still busy solving problems the industry doesn’t yet know it’s got. “You’ve got to see things differently. If you’re going to do what everybody else has done, you’re going to be the same as them. I’ve got all these slogans – we call them mantras – and one of them is: ‘Different isn’t necessarily better, but better is always different.’”

A long way to the top

White’s mid-70s band, Jade, was playing good gigs, appearing on the same stage as the Keystone Angels (later The Angels) and ACDC.

Drummer Tony Jex recalls Richard White as someone who just seemed to know a lot. “He’ll tell you it was through reading, but I don’t know. It was just fortunate we had someone in our midst who could fix the broken-down truck getting to a gig. One time we were waiting for our van to arrive with Richard, and it turned up late with Richard holding a can of petrol in the cabin and somehow feeding it directly to the engine.”

But Richard White didn’t like the sticky carpets of the music business.

“It was something I kept going back to with different bands, but only for a time. I’d get disenchanted again. Jade was earning money, but it wasn’t trickling down to us.” He started fixing guitars with skills learnt from a book.

Rock Repairs started in the garage at Bexley and counted ACDC’s Angus Young and the Angels as customers. “I had perfectly clean linoleum floors, peg boards perfectly etched out. All the guitars were sitting on felt.”

He still tells his staff about the customer who wanted his guitar re-fretted. White told him it would cost $85, and the customer arced up. “I’ll do you a favour,” White said. “If you can find anybody in Sydney that’s more expensive, I’ll put my price up for you because I’m the best.” He got the job.

One day, legendary guitarist Carlos Santana came in, needing a new guitar to be set up. White’s mate, Reg, was working for him doing the prep work. “He’s got a Dremel drill, and the drill breaks, and he stabs it through the face of the guitar,” Richard White recalls. “Not just any customer. THE customer.”

At that moment, White knew the guitar business was not going to scale: “My reputation is one Dremel drill bit away from complete destruction.”

Richard White

| Current worth: $10.51 billion |

| Worth in 2020: $1.6 billion |

| Age: 68 |

| Grew up: Bexley, Sydney |

| Graduated: Sydney Tech High School |

| Lives: Bexley Sydney |

| Born: Sydney |

| CV: Founded Rock Repairs. Founded Eagle Developments International (EDI) 1991.Changed name to CargoWise in 2006, then WiseTech Global in 2011. |

| Sector: Transport logistics software |

| Floated: April 2016 with IPO of $3.35. April 2023 share price went through $67, ie 20-times IPO |

| Market cap at IPO: $970 million |

| Current market cap: $26.7 billion |

| People: 77% of employees have equity. 18,000 customers in 170 countries. |

| Revenue: FY22 $632 million. Up 25% on 2021. |

| FY22 After-tax profit: $194.6 million. Up 80% on 2021 |

Issue Five of Forbes Australia is out today. Tap here for full access to this feature or to subscribe to the magazine.