From sleeping by the side of the road to running one of the world’s most recognised wine brands, John Casella’s journey is as extraordinary as the Yellow Tail empire he built.

This story was featured in Issue 16 of Forbes Australia, out Monday. Tap here to secure your copy.

John Casella Timeline

- 1959: Born in Brisbane

- 1982: Graduates in winemaking from Riverina College

- 1983-95: Works for Sergi family’s Riverina Wines

- 1993: Starts buying his own wine equipment

- 1999: Launches Carramar brand in the US, fails

- 2001: Launches [yellow tail]. Sells a million cases

- 2004: $70m upgrade of winery

- 2005: Starts building 100 x 1.1m litre tanks

- 2009: His father Filippo dies

- 2012: Builds a brewery next to winery and founds Australian Beer Co.

- 2014: His mother Maria dies

- 2014: Buys failing upmarket winery Peter Lehmann

- 2015: Buys Coonawarra’s Brands Laira from McWilliams

- 2016: Buys Morris Wines of Rutherglen from Pernod Ricard and starts distilling whisky.

- 2022: Sells 7,000 hectares and 35 properties to concentrate on brand building

- 2023: Buys Ampersand ready-to-drink brand

- 2024: Wealth estimated at $1.8 billion

As Yellow Tail grew to resemble more a refinery than a winery in the early 2000s, it engulfed the house where John Casella had grown up and where his parents still lived. The faded yellow weatherboards, the chickens and tomato vines were now shaded by the enormous wine tanks he’d just spent $70 million building to quench the world’s thirst for his wine.

So, in 2006 – the year Yellow Tail became America’s most popular wine after just five years in the market – he moved his mum and dad, Maria and Filippo, out to a new house near the car park where hundreds of locals now parked to come to work.

“See that light on in there?” the billionaire winemaker asks Forbes Australia, pointing from the dusty, cluttered veranda at a fluorescent tube in the old house. “I left that light on in 2006, and it’s still on 18 years later. I was taking some stuff out to the other house, and as I was walking out, I thought, ‘Should I switch the light off? No, I’ll leave it on.’ And it’s been on ever since. And whatever was in the fridge is still there.” Forklifts beep and toot just metres away as willy wagtails warble in the weeds.

Casella combines an almost psychic ability to see the future with a great attachment to the past. There’s the old weatherboard house, his dad’s 1969 grape press, the bottling line Casella bought – in defiance of the bank – whose purchase he credits with the making of him, the scuffed desk on which he still works. He’s clung to them all amid the gleaming new monster winery that he built so fast; it’s like he needs the old stuff to ground himself in the preposterous industrialist present in which he exists.

The scale of the winery cannot be grasped on the ground. Where 25 years ago there were vines, now there are 100 1.1 million litre tanks and many smaller ones. Sixteen B-doubles and semi-trailers an hour dump grapes from all over southern Australia into the bays. Australia’s fourth largest brewery is brewing beer out where the Trebbiano grapes used to grow.

In 25 years, John Casella has led Casella Family Brands from being a tiny bulk wine producer into Australia’s largest family-owned winery – fourth largest overall with revenues of $476 million in 2023, the last year for which figures are available, and profit of $26.5 million. Sixteen per cent of all Australian wine exports are Casella’s. They ship 138 million bottles a year. With his brothers Joe and Marcello, the Casellas are estimated to be worth $1.8 billion. They have left their competitors in the dust, shaking their heads and wondering what just happened.

Odysseys

Casella’s Sicillian father, Filippo, had been a prisoner of the British in World War II, captured in Libya, and impounded in India. He came to Australia in 1951 before bringing out Maria and their two oldest children in 1957.

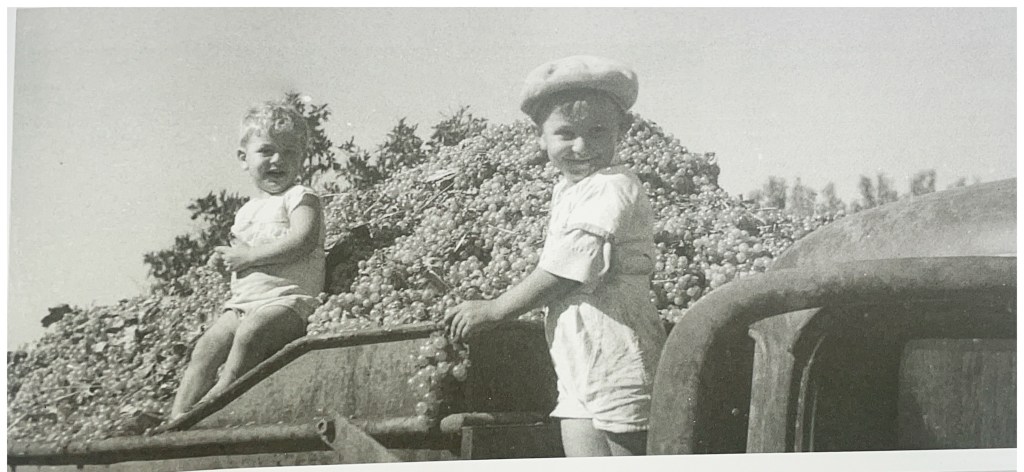

Giovanni “John” Casella was born in Brisbane in 1959, on the family’s annual migration between cutting sugar cane at Ingham in North Queensland and picking fruit on the irrigated red flats of NSW’s Riverina. By 1965, they’d saved enough to buy a 20-hectare block outside Yenda, a village 17km east of Griffith in southern NSW.

They planted peaches, apricots, plums and grapes. Casella is telling this story in a boardroom located where the apricots used to be. “Every Christmas day, we’d have to pick apricots. To this day, I don’t eat apricots. I hate them.” In 1968, Filippo took his Fargo truckload of grapes to the McWilliams winery just down the road, but was turned away at the weighbridge with no reason given.

Needing to do something with the load, Filippo made his own wine like his father and grandfather had done in Sicily. With no means of bottling it, he hit on the idea of selling it to his cane-cutting amicos in North Queensland. He’d send the wooden barrels on a truck, load the family into the Ford Zephyr and drive 2,100km north to “hand sell” them. Young John would remember sleeping by the side of the road, bathing in rivers, subsisting on rabbit and scrub turkey, and unloading barrels with ropes off the truck. He’d get to miss a month or so of school every year until he was about 15.

Asked what type of student he was, he tells the story of how four kids from Yenda Primary turned up on day one of high school without having been allocated classes. The deputy principal did it on the spot. “There were four of us in the line. He says, ‘B, B, C.’ He looked at me and says, ‘You’re in D.’” Casella might have looked slow, but he worked his way up and eventually went to Wollongong University to study economics.

“People think he’s Nostradamus or something.”

Accountant Roy Spagnolo

Casella dropped out after a few months and, the following year, 1979, switched to winemaking at Riverina College, now Charles Sturt University. “My father was a bit upset. He thought I should do something better than winemaking.” But Casella junior liked the idea of making something real rather than moving words and numbers on a page.

From 1983, Casella worked as chief winemaker for the Sergi family’s Riverina Wines [later Warburn Estate]. He was hankering to break out on his own, so he purposefully took on extra responsibilities. “I did the packaging, organized bottling, and sold the bulk wine so I knew who was buying, who was selling, and where the market was going. I looked after some of the finances and oversaw repairs and maintenance, so I knew about refrigeration.”

In 1993, still working for the Sergis, he started a side hustle and put a deposit on some winemaking equipment, plus a big shed for his parents’ place.

Around this time, Casella got talking to Roy Spagnolo at Spagnolo’s family’s vineyard, Calabria Family Wines. Spagnolo was an accountant, and Filippo Casella was facing a hefty tax bill.

For most years, Filippo had turned over $100,000 and made about $20,000 in profit, Spagnolo explains. But this year, the market for bulk wine had slumped and Filippo faced losing money and still getting slugged the tax. Spagnolo told the junior Casella their accountant was valuing the stock at cost and should do it at market value. Problem solved.

Casella came over as a client. Spagnolo also observed an intense work ethic. “He’d be working full-time [at Riverina Wines], then come at night to work on his own wine. He’d finish work, whatever time, go and do the groceries to feed his parents before he went home to his wife and family. He did that day after day.”

In 1994, Casella had some large tanks built cheaply without a deposit. He says the builder just wanted to find work for his crew, coming out of the early 90s recession. The UK export market was starting to boom, and prices were good. “I remember selling red wine for well over a dollar a litre. Last year, 30 years later, it was selling for 30c to 70c.”

The first vintage paid for the tanks. Casella wanted his own bottling line so he could move away from bulk. But the bank couldn’t see why he would want one when he didn’t even have his own label. “I said, ‘Well, you put a bottling line in when you don’t need it for the day you do need it.’ They couldn’t follow my logic, so I ended up going to the National Bank.”

With a you-beaut bottling line but no brand, another stroke of luck came along. The Arrowfield winery in the Hunter Valley had a fire and lost its bottling line. Casella bottled for them under contract. “That effectively paid for my bottling line.”

By 1999, he was doing enough bulk wine and contract bottling to keep 30 staff busy. He hired an export manager, John Soutter. “My parents said, ‘What do you need an export manager for? You’re selling all your wine.’” But Casella had the same philosophy as with the bottling line: get it before you need it.

Soutter took a newly minted brand, Carramar Estate, to the US, but it didn’t go well. The first batch had dud corks. The wine – and the brand – were tainted.

Casella went to the US distributor, Bill Deutsch, of Deutsch Family Wine & Spirits. “I said, Bill, we’ve let you down. If you want to find another Australian supplier, you’re quite welcome. We don’t make the corks but are responsible for them.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry, John. You keep going.’”

Casella went out and, in early 2000, bought a pre-designed wine label from Adelaide designer Barbara Hartness, with an indigenous-themed kangaroo and a name, [ yellow tail ]. The brackets are important, apparently.

Casella sent Soutter back to the US and told him: “Do not change the label. Somebody won’t like the kangaroo or the colour. We will still be talking about it for years. We need to show them we know what we want and who we are.”

Deutsch says he could see that Casella wasn’t just trying to produce another wine, “He was rethinking the category entirely,” Deutsch tells Forbes Australia. “By softening tannins and acidity, he crafted a smoother, more approachable style that appealed to people who didn’t typically drink wine … We saw the potential immediately – not just in the product but in the vision behind it. That’s why we believed in John then, and it’s why [ yellow tail ] remains one of the most successful brands in the history of wine.”

Textbook manoeuvre

Two business professors, W Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, would later write about what John Casella. They note in their textbook, Blue Ocean Strategy, that wine usually sold on prestige and complexity of flavour at every pricepoint – even though the bulk of Americans found this to be a turnoff.

“By looking at the alternatives of beer and ready-to-drink cocktails, Casella Wines created three new factors in the US wine industry – easy drinking, easy to select, and fun and adventure,” write the professors. “This allowed the company to dramatically reduce or eliminate all the factors the wine industry had long competed on – tannins, complexity, and aging. With the need for aging reduced, the working capital required was also reduced. The wine industry criticized the sweet fruitiness of [yellow tail], but consumers loved the wine.”

“They spent more time pooh-poohing us than worrying about how they would compete with us. ‘It’s too sweet, it’s not selling, it’s not going to last.’”

John Casella

Casella is chuffed that a textbook would devote an entire chapter to him but plays down his insights as “intuition”. And the wine tasted much the same as his father made. They sent their first bottles to the US in January 2001 for a June launch. But each morning, he’d get up and see faxes rolled up on the floor – 10 to 15 every morning. Every one a fresh order … For a container load!

He couldn’t quite believe what was happening. And couldn’t quite see how he’d cope.

Casella had sold Hardies a large amount of bulk wine that was still on site. He was soon on the phone to them: “Would you like to sell it back to me?” Hardies made a tidy margin without ever seeing the wine.

Deutsch had expected to sell 25,000 to 45,000 in the first year. But they passed that in weeks. Casella needed to find bottles, grapes, wine, labels, staff, contract bottlers. He was getting “capsules”, the foil sleeves on the bottle necks, from two companies. “We’d buy as many as we could from one company. They’d put us on stop-supply, so we’d get as many as we could from the other. They’d put us on stop-supply. Then we’d pay the other.

“We just kept juggling until I went to Bill Deutsch. I told Bill, ‘If you could assure the financiers that you’ll pay in 90 days, they’ll lend me the money to make more wine.’ He goes, ‘I’ll do better than that. I’ll pay you in seven days.”

It was already obvious to Deutsch how much more Yellow Tail they could sell. “It wasn’t a difficult decision,” he says.

It gave Casella breathing space.

There was a stuff up at the bottle company so he had half a million bottles delivered from Europe in a giant Antonov cargo plane. “It cost me an absolute bomb, but I would rather lose money than lose shelf space.”

Fortune continued to smile. In February 2001, Southcorp [owner of iconic brands like Penfolds, Lindemans and Wynns] bought Australia’s largest family-owned wine company, Rosemount, which was the second biggest Australian wine in the US. Rosemount stopped buying bulk wine off the market, adding to an already growing oversupply of grapes and wine. So, while high grape and bulk wine prices had allowed Casella to grow early on, he could now swoop in and buy good wine cheaply.

The handshake

Roy Spagnolo was fulfilling the cliched accountant role of tearing his hair out as Casella pushed the envelope, taking out big loans, then giving loans to growers or buying water entitlements for them – anything to secure grapes.

“The banks and everyone was saying ‘consolidate, consolidate’,” recalls Spagnolo. “And he said, ‘No, if I don’t take this opportunity now, I won’t get another chance.’ Anyone else would have just done it slowly, and they wouldn’t have made it. He took the risk. He could have gone broke that year. He wasn’t worried about himself; he was worried about his parents. So he set up a Maria Casella super fund, so if he went broke by being entrepreneurial like he was, the parents would have enough to survive.”

Richard Stott was pivoting into grapes from being the country’s largest tomato grower. He had 50 hectares under vines three weeks from vintage when the winery told him they wouldn’t take his grapes that year. A consultant put him in touch with Casella, 32km north up a dead straight road. Stott had never met him. “We sat down across the table, and after four or five minutes, I knew it was going to be a pretty good marriage.”

Price wasn’t discussed, but Casella said Stott would always be better off with him. They stood and shook hands across the table, and for the last 23 years, Casella has taken every grape Stott has grown. “And I always have been better off,” says Stott. “He’s always paid equal to or better than other wineries. He’s conscious that he needs his growers. He knows he needs to think of them through hard times to get his grapes in good times.”

Satisfaction

The Aussie dollar hit record lows below US50c through 2001. Each $US6 bottle sold fetched about US$2.50 for Casella, of which 30% was profit. They sold a million cases in the first year – 12 million bottles – and 25 million cases in the first five years. Yellow Tail’s Shiraz became the top-selling red in the US in 2003, and Yellow Tail became the top-selling wine label by retail value in 2006, a position it held for more than a decade.

Casella was suddenly seriously rich.

“He’s always thought of everyone else,” says Spagnolo. “Like, when he could afford to buy a nice car, he bought a new Mercedes E-Class for his father, not for himself.”

Asked what Filippo thought of his success, Casella tells the story of driving his dad to the McWilliams winery, where he’d been turned away 40 years earlier. “Do you remember these weighbridges?” Casella recalls asking him. Filippo nodded. “We own them today.”

“It was some of the best-spent money I’ve ever spent,” Casella says. “The satisfaction of it.”

Casella’s international marketing manager Libby Nutt remembers the 2004 Jimmy Watson Memorial Trophy, arguably Australia’s most prestigious award, when Casella entered a special-edition cab sav. “It came up on the screen that Yellow Tail had won. Remember, it’s up against wines that retail at $100. Everyone went deathly silent. ‘How could that happen?’ John took great satisfaction in that, but he’s much too modest to say so.”

In a voice so quiet the transcribing tech can barely make him out, Casella says that if he had filled his bottles with Penfolds Grange Hermitage, long regarded as Australia’s best wine, he would not have sold as much as he has. “The best thing was that the major companies couldn’t believe this little company out of nowhere was doing so well. They spent more time pooh-poohing us than worrying about how they would compete with us. ‘It’s too sweet, it’s not selling, it’s not going to last.’ By the time they realised it wasn’t too sweet, that it was what people wanted, and produced their own versions, it was too late. We’d already established ourselves.”

Nostradamus

Australia was in the “Savalanche” in the first decade of the century as Sauvignon Blanc took over from chardonnay as the country’s favourite. But Casella could see Pinot Grigio was getting bigger overseas. His global marketing manager, Libby Nutt, remembers telling their US distributors that Yellow Tail was going to produce a Pinot Grigio and being told they were crazy.

“John doesn’t like to be told no,” says Nutt, “And he’s like, ‘well, I can make a Pinot Grigio, and I can probably do a better job as well.’” They did 250,000 cases in the first year and by 2008 were doing nearly a million “and today are over 1.5 million cases, and it’s 13% of our total Yellow Tail volume,” says Nutt.

Casella was also using his buckets of money to buy vineyards suffering from the low grape prices all over the country. “People think he’s Nostradamus or something,” says Spagnolo. “He bought farms when no one wanted them, then he built up a good portfolio, and he sold two-thirds of them not long ago, just before the market crashed. He is the board, so he can make a decision on the spot. We can be talking, yep, bang, do it.”

Spagnolo sees Casella often defying marketers or US insiders to go with his gut. “Then it turns out he’s right. Maybe he is psychic.”

Yellow Tail found the UK a much harder market to crack than the US. In 2015, it looked like it would get even tougher when the Melbourne-based global player, Treasury Wine Estates, bought Yellow Tail’s UK distributor Percy Fox.

Treasury, a competitor of Casella Family Brands, had no interest in distributing its wine, says marketing manager Nutt. “John was like, ‘Well, I need to go and think about how I own the distribution network in other markets.’” It ended up that he poached the entire Percy Fox team and brought them all in-house. For the past ten years, they’ve only had Casella’s wines to sell. “By having our own team, we’ve become the number one wine brand in the UK market by value and volume,” says Nutt.

The American market has tailed off in recent years as competitors have copied the Yellow Tail textbook, but what it’s lost there, it has gained in the UK and other markets.

Yellow Tail volume by top 3 markets

- US – over 5 million cases. 43% of total volume

- UK – almost 4 million cases. 34% of total volume

- Australia – over 900,00 cases. 8% of total volume

“Success drives him,” says Nutt, “but he’s not afraid of failing in the sense that he’s always willing to try new things, and I think that probably comes from not growing up with a lot, so he’s not really concerned about going back to that.”

For his part, Spagnolo was doing well out of the relationship. On the back of having a billionaire client, he’d springboarded his little Griffith firm into the Sydney and Melbourne CBDs and was now representing a raft of famous folk, from television’s Karl Stefanovic and various Wiggles, to models and footy stars.

He bought a Maserati and John Casella wasn’t happy.

“He says, ‘Roy, you can’t drive a Maserati around town’,” recalls Spagnolo, “‘The growers are doing it tough.’” Casella had the accountant take his own 2015 Holden Statesman. “It’s presentable but not showy. That’s the type of person he is. He drives a ute. He wants to show that he’s not better than someone else.”

Australia’s biggest wine companies

| Company | Ownership | Major Brands |

| Treasury Wine Estates | ASX listed | Penfolds, Lindemans, Wolf Blass, Wynns |

| Pernod Ricard Winemakers | French listed | Jacobs Creek, St Hugo |

| Accolade Wines | US private equity | Hardys, Grant Burge, Berri Estates, Petaluma, Banrock Station |

| Casella Family Brands | Casella family | Yellow Tail, Peter Lehmann, Morris of Rutherglen |

| Hill-Smith Family Estates | 5th generation Hill-Smith family | Yalumba |

| Australian Vintage | ASX listed | McGuigan |

| De Bortoli Wines | 3rd generation De Bortoli family | Yarra Valley Estate, Noble One |