Australia’s 50 richest is out for 2024 and despite some position swapping, due in part to a bounceback in tech fortunes, the list remains largely unchanged – with only two newcomers managing to break in. So exactly who are Alexandra Burt and Leonie Baldock?

Fortunes drawn from iron ore, an export mainstay, remain unshakeable at the top. Mining magnate Gina Rinehart held on to her long-standing position as the country’s richest person, though her wealth dipped slightly to US$30.2 billion.

Mining heiress Angela Bennett – who holds a significant stake in Wright Prospecting, founded by her late father, Peter Wright – came in at number 43 with a wealth of US$1.25 billion. However, it was Bennett’s two nieces Leonie Baldock and Alexandria Burt who made their debut on the list as the only two newcomers.

Each sister inherited US$400 million when their father, mining magnate Michael Wright died in 2012. The pair are ranked 46th on the rich list with a wealth of US$1.2 billion.

Older sister Baldock, now 52, had gravitated towards running the family’s mining business, Wright Prospecting, while Burt, 50, had already taken over the Margaret River winery, Voyager Estate, founded by their father in the early 1990s.

Like their father, who famously drove an old Volvo, the sisters have shunned ostentation and shrunk from the limelight.

Burt has sat on numerous wine industry boards. She is cofounder of Sydney-based Australian Futures Project – which aims to end short-term thinking in Australian politics – a board member of Tourism Australia and the Australian String Quartet and a patron the West Australian Ballet. Baldock has a lower profile.

“They don’t drive massive cars or live in big, flash houses,” former employee Cliff Royale has said. “They’re not social people. They give a lot of money to charities. They do a lot of work in the community, but they’re not the sort of people who like to be seen out in public.”

Both routinely decline media requests and so much of what is known about them has been gleaned in the courtroom. Ever since they inherited their father’s estate in 2012, Baldock and Burt have been in court fighting Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting for what they say is theirs – and defending their assets from claims against them by other members of the Wright family, including their illegitimate half-sister, their African American stepmother and their uncle.

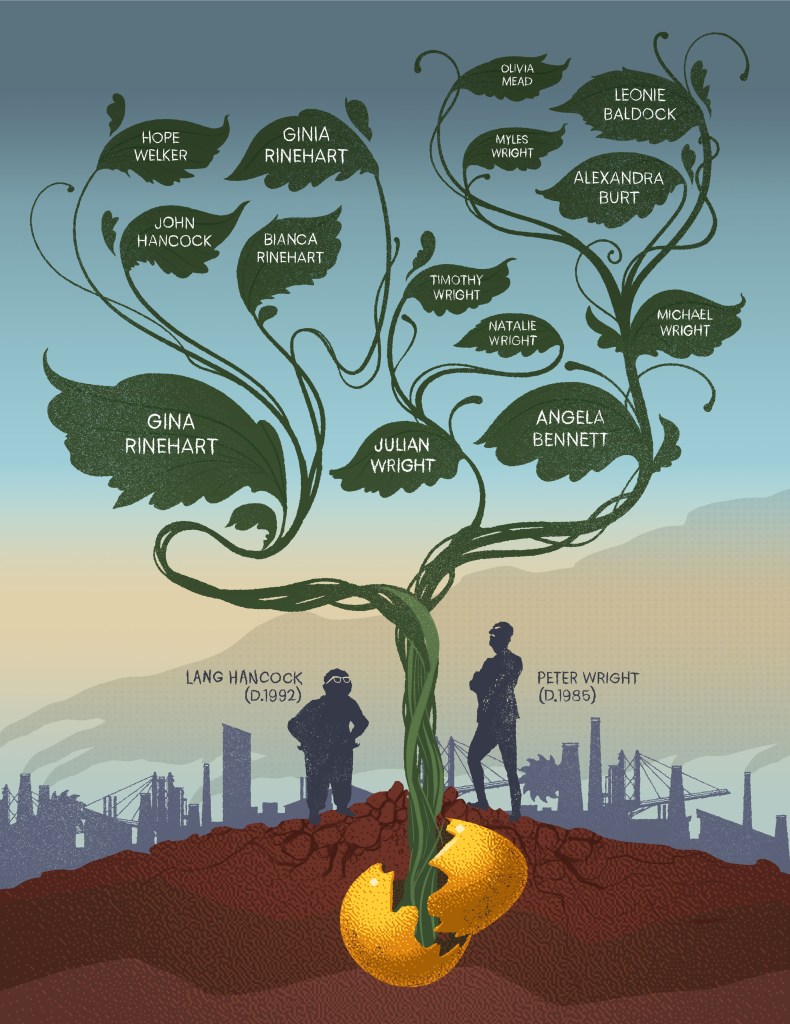

The family money tree

To understand it all, you need to go back to the source of their wealth – the iron-red dirt of the Pilbara and to a deal struck by their grandfather, Peter Wright, with miner Rio Tinto and Wright’s more well-known business partner, sheep farmer and prospector Lang Hancock, 61 years ago.

While Lang Hancock was the public face of the Hancock-Wright partnership, bold in his political and media forays, Peter Wright shrank from public view (as does his family still). The first mining venture of the 50-50 partnership was to launch the asbestos mine at Wittenoom, which they sold out of in 1948, long before it became infamous for its asbestosis-related death and disease.

In 1952, Hancock claimed to have discovered the world’s richest iron ore deposit while flying low to dodge bad weather in his plane.

Eleven years later, Wright – an accountant who’d known Hancock since school – negotiated the details of the 1963 agreement with Rio Tinto that saw them receive 2.5% of gross sales on all minerals, except manganese, extracted from their mining titles.

It was the deal that would set up their descendants for generations.

The best-laid plans

In 1982, the two men, now in their 70s, started to correspond about dividing up the partnership in preparation for their deaths. They decided to keep ownership of all the assets within the partnership for tax reasons. Still, they would split up those assets so each managed specific properties while ultimately sharing the profits. It was clear from the correspondence that it was intended to be an equal split, according to Justice Michael Murray in his 2010 summation of the matter in the Western Australian Supreme Court.

Such was their trust in each other, Wright and Hancock shared the same Sydney solicitor in drawing up and signing the documents for what became known as the “1984 Agreement”.

Wright was to manage the Rhodes Ridge and Giles iron ore tenements. Plus, some coal deposits in Queensland, Manganese in WA, and most of the town of Wittenoom.

Hancock got the McCameys, Marandoo and Shovelanna iron ore tenements, some limestone interests, chrome base metals, and the Wittenoom Hotel.

The following year, Wright died suddenly in Thailand, aged 77, and control of the partnership fell to Hancock, who, two months earlier, had married his Filipina former maid, Rose Lacson. (His first wife, Hope – mother of their daughter Gina Rinehart – had died in 1983.)

In 1987, Peter Wright’s two oldest children, Michael Wright and Angela Bennett, paid their younger brother, Julian Wright, $6.82 million for his one-third share of Wright Prospecting at a time when the price of iron ore was below $20 a tonne and the royalties from their holdings had not yet started to flow. Julian’s attempt to claw back that deal as the price of coal shot past $100 a tonne and hundreds of millions of dollars started to flow to his siblings remains in the courts, 37 years later.

When Hancock died in 1992 – in the guesthouse of his Perth mansion Prix D’Amour with a restraining order on Rose – the handover to his daughter did not go so smoothly.

First, Gina had to fend off claims to the estate by Rose – who three months after the death had married real estate agent William Porteous. Then Gina made allegations of suspicious death against Rose – claims which would take ten years to play out in an inquest that found Hancock had, in fact, died of heart disease.

By that time, Gina had taken charge at Hancock Prospecting and built it into the powerhouse that it is today. In 1997, Hancock Prospecting made an offer to buy the Wrights’ 25% stake in Rhodes Ridge. The Wrights shot back saying they would exercise their right to 50% of Rhodes Ridge – one of Australia’s richest then unmined iron deposits. The tenements near the Pilbara town of Newman are estimated to hold at least two billion tonnes of high-grade iron ore. (A price of US$100 a tonne would therefore value it at US$200 billion.)

Related

The Wrights claimed Rhodes Ridge was being held in trust by Hancock Prospecting for Wright Prospecting under the 1984 agreement but Hancock Prospecting said that agreement had been superseded.

Negotiations went nowhere and in 2001, Michael Wright and Angela Bennett launched legal action against Hancock Prospecting claiming 50% of Rhodes Ridge. Rio Tinto owned the other 50%.

This case is completely separate to that currently being fought between the Wrights and Hancocks in the West Australian courts. This first case dragged on for more than a decade. And it took a toll on the publicity-shy Wright family. Michael was forced to admit to the strained relationship he had with his sister, Angela Bennett [Now No. 43 in Forbes’ Australia’s Richest list with a net worth of US$1.25 billion].

When Angela – the most notoriously private of all the Wrights – testified in 2007, she divulged that she was recovering from a brain tumour. She warned the court that she sometimes said yes when she meant no.

Two years later Angela downsized from her high-walled, Mediterranean-style compound by the Swan River. She sold it to the mining up-and-comer, Chris Ellison of Mineral Resources [No. 49 on Forbes’ Australia’s Richest list with US$1.05 billion] who smashed Australia’s then residential property record paying her $57.5 million for the property. [The selling agent was Rose’s husband Willie Porteous.] Fifteen years later, the sale retains the West Australian residential property record. Bennett reportedly moved into an $8-million Perth penthouse.

The grapes of wealth

Michael Wright, a teetotaller who drove an old Volvo, had become an enthusiastic winemaker at his Margaret River vineyard, Voyager Estate. He spent lavishly on it, building, for example, a traditional underground barrel room with a vaulted ceiling rather than the mundane air-conditioned shed of an ordinary vineyard.

When his daughter Alexandra Burt came to work for him at the vineyard in 2005, she pushed him into running the place more like a cost-conscious business, but while he reportedly railed against her lack of flare, they apparently worked well together.

The Wright-Hancock case dragged through the courts with incessant appeals and attempts to stay, but in 2010, Justice Murray had his billion-dollar decision ready. He noted: “The evidence would tend to support a conclusion that, following the death of Mr Hancock, those acting in senior management roles for the defendant (Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd) were inclined to pursue negotiations with respect to the development of Rhodes Ridge with Rio Tinto, apparently without reference to the (Wrights).”

Murray ruled that the Hancock Prospecting had to hand over its 25% stake in Rhodes. That decision provided a large chunk of the fortune that has propelled Peter Wright’s already-wealthy descendants into another stratosphere of affluence.

Justice Murray complained that the system needed to rethink how it handled such cases where both sides are “unconstrained by considerations of time and cost,” because of the enormous court resources they consumed, inhibiting access to justice for more ordinary folk.

Hancock Prospecting appealed Murray’s decision and it would be four more years before the company handed over the assets to Wright Prospecting as per the court order.

The forgotten siblings

Michael Wright never got to see the money. He died, aged 74, in April 2012, leaving two of his daughters, Leonie Baldock and Alexandra Burt, about $400 million each. His son, Myles Wright, then 33, however, got just $20 million. Myles, a musician and composer, had chosen to eschew the family business, studying jazz music at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts and then in the US. At the time of his father’s death, he was a university music teacher in Perth. He has since gone on to compose for theatre and advertising. This year, he released the album Gamer – big-band jazz arrangements of retro video game music.

Michael Wright however, had a third daughter. Then 16-year-old Olivia Mead only met her half siblings at their father’s funeral. Mead was the product of a relationship between Wright’s third and fourth marriages.

Related

Mead, raised by her single mother, Perth musician Elizabeth Mead, was left a $3-million trust fund she could not access until she turned 30. And then only if she met certain conditions: For example, that she not be an alcoholic or drug addict; that she not follow any religion other than a traditional Christian faith; and that she not be convicted of a felony.

Mead caused something of a sensation when she took Baldock and Burt to the WA Supreme Court in 2015 and announced to the world that she was Wright’s daughter and demanded a larger portion of the Wright fortune. Tattooed and with something of 1950s rocker vibe, the 19-year-old Mead perhaps overplayed her hand when she made a list of what she thought she needed to last her for the rest of her life – a diamond-studded guitar, a crystal-covered grand piano, a Mexican walking fish, a $2.5 million house, an Audi A4, five pairs of $5000 shoes every year, $40,000 annually for holidays, and Pilates lessons for the next 75 years.

The judge awarded her more than she asked for $25 million, saying it was but a “rounding error” for Baldock and Burt who wouldn’t even notice it was missing. “And they can rest easy in the knowledge their half-sister will be financially secure for the rest of her life.” They didn’t rest easy however, and took it to the Court of Appeal which sided with them, reducing the payout to $6 million.

Mead took her sisters to the High Court seeking to get her $25 million back, but failed to persuade the highest court in the land of the merits of her argument.

Burt and Baldock also faced a legal challenge to the will by their stepmother, Michael Wright’s fourth wife, Mary Ann, a striking African American who he’d met on a bus at a New Orleans jazz festival. Married for 15 years, she had inherited the couple’s Mosman Park mansion with views out to Rottnest Island, but felt she needed more. That matter, more in keeping with the family’s private style, was settled out of court.

$250,000 a day

Back in 2010, even as Justice Murray was handing down his decision that gave them Rhodes Ridge, the Wrights were already planning similar action against Hancock Prospecting over Hancock Prospecting’s Hope Downs mining tenements – which today consist of four very large open pit mines all developed with Hancock money.

Fourteen years later, Justice Jennifer Smith’s decision on who owns what and who is owed what part of the billions that have – and will – flow from there is pending in the Western Australian Supreme Court.

The two dozen lawyers attending last year’s 51-day trial were estimated to have cost $250,000 a day.

More wine

Baldock and Burt’s uncle, Julian Wright used some of his $6.85 million he received from his siblings to buy Marri Wood Park vineyard in Yallingup which he converted to biodynamic and continues to run. You can drop in for a drink.

Julian was no babe in the woods. He had a commerce degree and an MBA from North Western University in Chicago and worked in the finance industry in Chicago before returning to Perth in 1976. He’d been general manager of his father’s newspaper, the Sunday Independent, and had a share in a Perth financial advisory firm.

He never forgot the 1987 deal he signed with his siblings Michael Wright and Angela Bennett.

In 2001, with royalties of $8 million a year now flowing to Wright Prospecting, Julian’s children, Timothy and Natalie Wright, had sued their uncle and auntie for an 11% stake in the company. It was later revealed in court that they had come to an out-of-court-agreement for $70 million in order to put an end to the matter. (The litigation funder, IMF, reportedly bagged $22 million of the settlement.)

But Julian didn’t let go. He spent years gathering evidence about the circumstances surrounding his sale of his share. He took his sister and nieces – Burt and Baldock – to court in 2017 alleging that his siblings – Angela and Michael – duped him into selling his one-third stake in Wright Prospecting for so little.

He alleged they had “fraudulently misrepresented” the value of the company, showing him books that valued its assets at between $12 million to $15 million with no mention of royalty streams owed to it.

In 2021, the Western Australian Supreme Court saw the younger brother’s point. “Julian has established his causes of action in deceit and equitable fraud in relation to Michael and Angela acquiring his interest in Peter’s estate,” Justice Rene Le Miere wrote in his judgement on the case. But he ruled that Julian was not entitled to get back his one-third stake because of the 2008, $70-million settlement, which included a commitment from Julian not to bring further legal action. Costs were ordered against him.

Julian has continued to appeal Justice Le Miere’s decision, and it currently awaits a decision.

Feet grounded, wealth skyrocketing

Burt took over management of Voyager Estate winery, in 2005 and then took full ownership in 2018. She has founded the Landsmith Collection, which plans to operate high-end, mostly remote, destinations like Bullo River Station in the Northern Territory which was made famous in the books of the later Sara Henderson.

The decision in Julian Wright’s appeal has been “reserved” with no indication of when it might be handed down. The vast wealth at stake in that case rose dramatically last year too, when Wright Prospecting refreshed a 50-year-old joint venture deal with Rio Tinto to develop a new iron ore mine at Rhodes Ridge; a move that could see the company’s annual profit increase four-fold. The 40-million tonne per annum mine could generate up to $1 billion a year for the family.

While no one is saying how much all this frenetic legal activity is costing, it’s worth noting that Wright Prospecting clocked up $9.8 million in legal fees in the two financial years before the trial even started and they spent $12 million last year, according to its published accounts. Never mind, last year’s mining royalties brought in $235 million.