Synchron’s adoption of artificial intelligence into its brain-computer interface is a step towards transhumanism, says the company’s brain-surgeon CEO Tom Oxley, but that’s not why they’re doing it.

The incorporation of a large language model into Synchron’s brain tech keeps the Australian-founded, US-headquartered Synchron ahead of its main rival, Elon Musk’s Neuralink, in the race to market with a brain-computer interface that allows people to operate a computer with their thoughts.

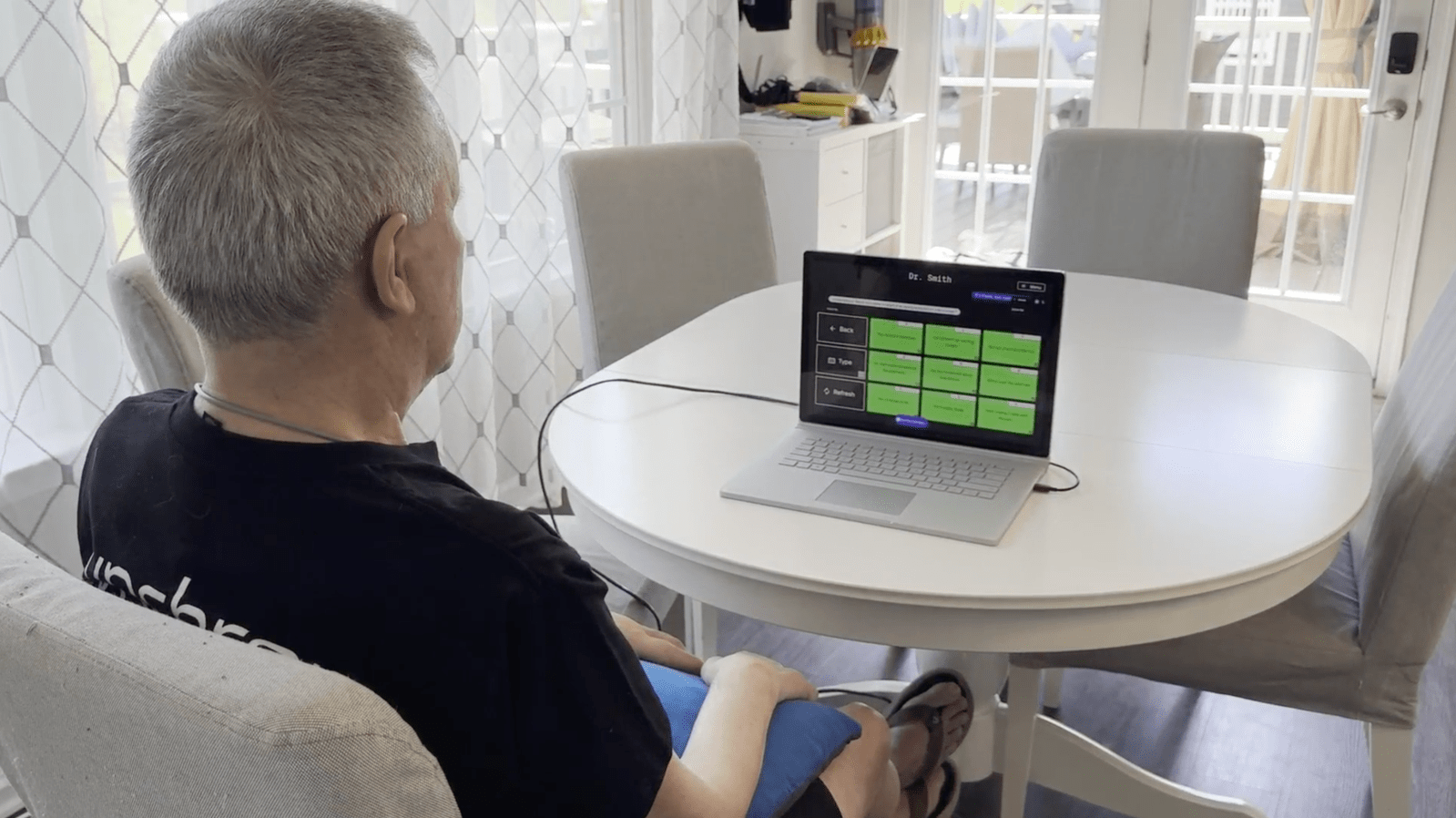

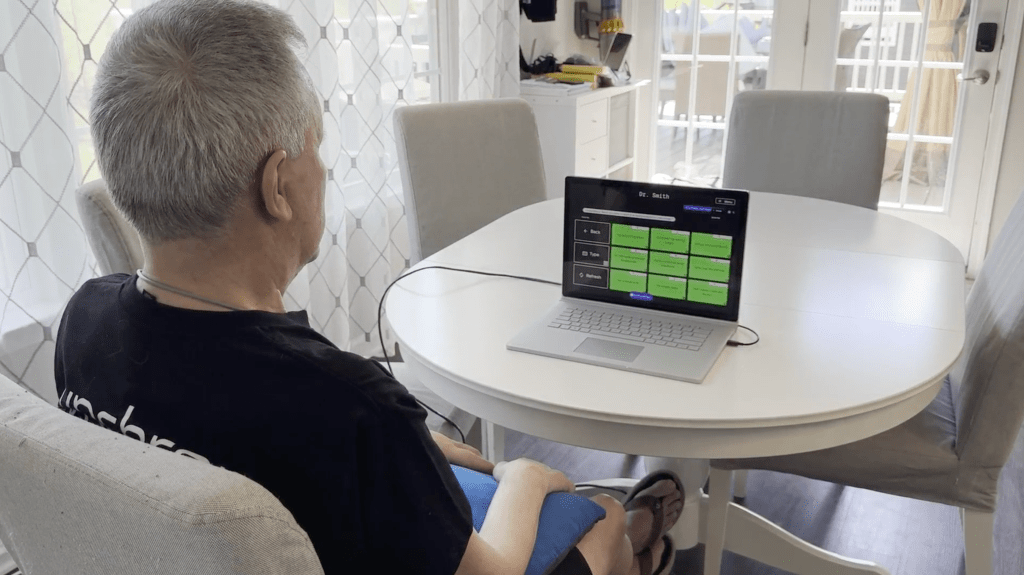

It has announced that one disabled patient has started using an artificial intelligence feature to help him communicate at “conversational” speed.

Synchron was founded by Oxley and biomedical engineer Nick Opie in Melbourne in 2012. It put its first brain-computer interface in a human in Melbourne in August, 2019, and has since then inserted it in nine other patients – getting the “stentrode” into their brains via a vein.

Neuralink inserted its first device in a human in January, 2024. That patient remains the only person to have experienced Neuralink’s robot-surgery inserted device.

And while Synchron might be up against the world’s richest man – whose Neuralink raised more US$300 million at its last funding round – Synchron is no small fry. It counts DARPA, Khosla Ventures, ARCH Venture, Bezos Expeditions and the Gates Foundation among its backers, having raised a total of $US145 million at a valuation of about US$1 billion.

Synchron is still conducting its “feasibility” trial, and after the tenth patient reaches their one-year milestone later this year, it will seek FDA approval to begin a 50-person “pivotal” trial – the final hurdle before commercial approval.

Part of the pivotal trial criteria is that Synchron needs to show that its product makes a meaningful difference to the patient’s quality of life. The incorporation of the AI will go a long way to do that, says Oxley, bringing patients who have lost the ability to speak or use their hands up to conversational speed in their communications.

Currently a brain-computer interface works by the patient using their brainwaves and eyes to move a cursor on a screen – like navigating a Netflix menu’s keypad. It is slow.

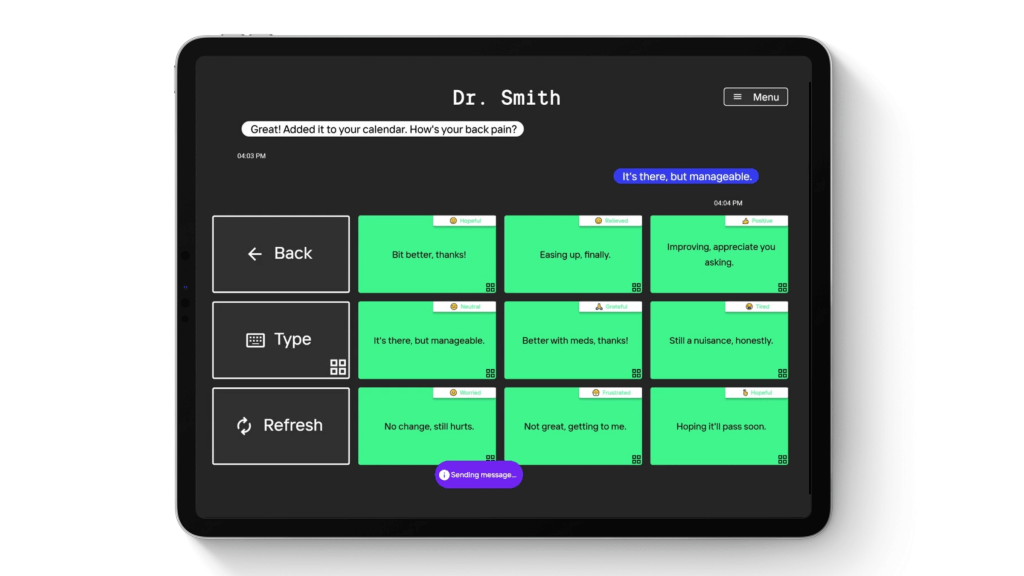

But Oxley says the new AI feature, utilising OpenAI’s GPT-4 doesn’t need to follow the eyes and speeds up the process by anticipating what the patient wants to say and offering them a range of single-click options to say it.

Both the inputs and outputs can be a voice.

Synchron is also adding emotions to the equations.

“You know how when you respond to someone, you generally feel something before you come out with the words,” says Oxley. “So we have a layer where the user selects an emotional category of how they want to respond.”

They’re starting with the simple categories of “positive” “neutral” and “negative” but are looking at adding layers into those like “frustrated” or “impatient”, says Oxley. “Then we get the GPT to generate prompts based on the emotional place you want to come from. We’re calling it emotional categorisation.

“We’re going to keep exploring what makes best sense to present to the users.”

Elon Musk has, from the beginning, been open about his long-term goal of using a brain-computer interface [BCI] to extend the performance of healthy humans beyond current limits, so-called Transhumanism.

Related

And while Oxley admits, this technology is a step towards transhumanism, he says it’s not where Synchron is heading. “These are all small steps. I’m not sure, to be honest, how to think about transhumanism. I do think BCI lends itself to a moment when the technology passes the level of functioning the human body can achieve. That’s probably the critical moment. Steve Jobs used to speak about how the iPhone was built around the function of the hand. That’s traditionally how we build technology for control – control around how we use it, and BCI eventually moves to a point where it surpasses what the human body is capable of in terms of control. So that moment’s out there. It’s a moment we’re not thinking about. We’re focused on, that which is needed to help people whose bodies are failing.”

The AI chat feature has only been used by one patient to date, an American motor-neurone disease sufferer identified as Mark. “As someone who will likely lose the ability to communicate as my disease progresses, this technology gives me hope that in the future I’ll still have a way to easily connect with loved ones. This will be a game changer,” Mark said in a release issued by Synchron.

Talk of transhumanism is dangerous “because it detracts from the mission”, says Oxley. “The mission is to help people whose bodies are failing to stay connected in the world. The mission is not to achieve transhumanism. I think there’ll be a moment where we’re starting to think about what that means, it raises a bunch of moral and ethical questions, which we have to take very seriously and I don’t yet have a moral framework around transhumanism that I feel comfortable with.”

Comfortable or not, Oxley says the BCI race is getting more crowded. “It’s heating up. There’s something like six companies that I’m aware of that are now moving into this space, and I’m starting to hear rumours of some big tech starting to play in this space as well … There’s interest because the technology’s got a horizon that lends itself to technology control that’s not currently possible without human bodies, so big tech is starting to realize that this potentially a very large market.”