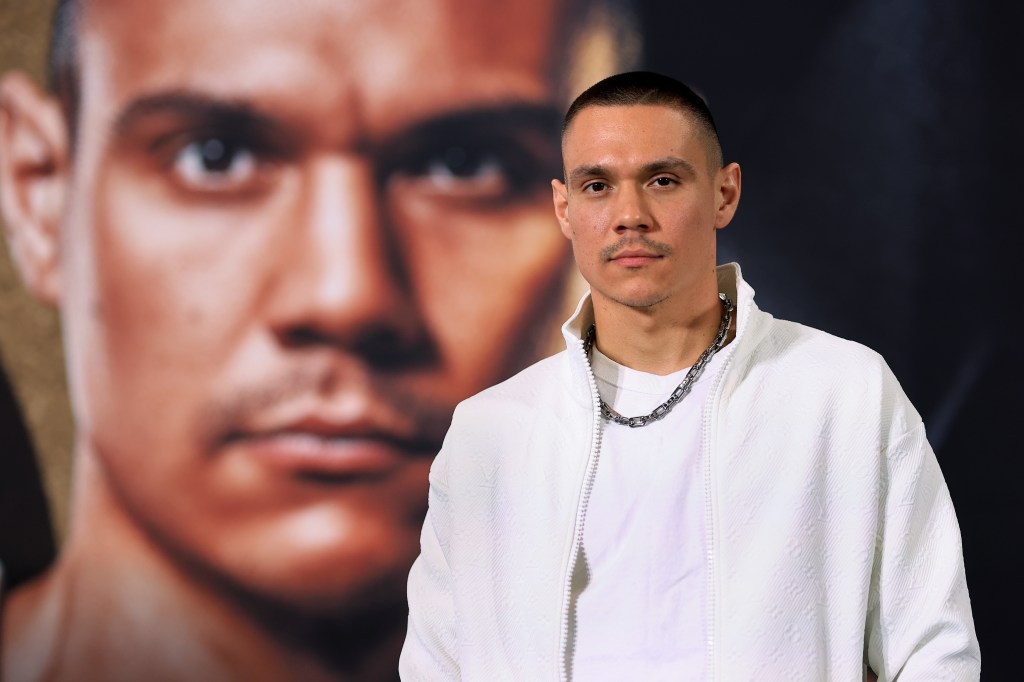

Professional career, boxer Tim Tszyu was preparing to battle the undefeated “KO King”, Vergil Ortiz Jnr when doctors ruled him out. Tszyu talks to Stewart Hawkins about what it takes to bounce back from setbacks, emerge from his father’s shadow and reach the top of one of the toughest sports on the planet.

Tim Tszyu is surprisingly gently spoken.

However, it’s not what he says – he talks tough – rather, it’s the way he delivers it.

The super welterweight fighter stands about 174cm, 5’8” and a half, in US measure, and looks much younger than his 29 years and 25-pro-fight record would suggest. He’s lithe, fit, and moves with the grace of a gymnast – despite a punishing recent fight – and you can almost feel the man’s physical power as he shifts about the room.

So, there’s something slightly disarming when he looks you in the eye and gently says of that recent bout: “I was ready to die that night for victory.”

We’re talking at his Sydney home shortly after he returned from the Tiger Muay Thai and MMA training camp in Thailand, where he went following his controversial single-point loss in Las Vegas to Sebastian Fundora in March. He had been preparing to fight Vergil Ortiz Jnr, an undefeated American who has won all his fights with knockouts. Frustratingly for Tszyu, the world title bout was cancelled because medics ruled he had not had enough time to recover from a head injury.

Tszyu’s suitcase is lying open on the hallway floor, gear spilling out, marring the otherwise spotless, lightly furnished modern home. (You get the idea he doesn’t spend much time sitting on the couch or hanging out in this place.)

That fight he was describing was a bloodbath. An elbow blow, judged to be accidental, from Fundora in the second round opened a deep cut on Tszyu’s head that penetrated to his scalp and then bled profusely for the next 10 rounds. He fought half-blind. He refused to stop fighting. Some commentators argued it should have been called a “no contest”. The single-point decision against Tszyu at the end, attested to an almost super-human effort but lost him the bout to the American southpaw.

For anyone who watched that fight – the sheer grit and the determination to not give up was inspiring. I was intensely curious about where that drive and courage came from.

As we talk about how that fight made him feel, Tszyu – a forward, hard-hitting fighter who earned the nickname ‘The Soul Taker’ partly because of his relentless attacks in the ring – admitted his biggest fear throughout his career: losing. Well, maybe not so much losing as how he’d react to a loss, how he’d feel about it – because he’d never experienced it. Enigmatically, about that last fight, he stated: “It didn’t feel like a loss”.

“It was the unknown,” he says.

“I was not depressed. I didn’t feel sad. I wouldn’t say I felt angry. There’s a good saying, ‘Don’t get too high from your wins and don’t get too low from your losses’. Never feel sorry for yourself, no matter what.

“And I was able to, during my holiday, do half a marathon. And that’s when I realised, you know what? Life is all about challenges. It ain’t supposed to be easy. It’s not supposed to be flowers all day, every day – you need hardships. And that’s what it’s all about.”

“When you do something, go all in. No backup plan.”

Tim Tszyu

He admits that sometimes it would be “technically smarter” for him to do other things, but he smiles and says, “My pride sometimes outweighs that.”

“My dad always used to say, you’ve got to be able to die in that ring for victory. And I have that in me. My dad said when he finished his career, he felt that the only reason he didn’t want to fight again was because he didn’t want to die for that anymore. He was ready to say he quit.”

No such thing as a silver spoon

Tszyu is the elder son of Kostya Tszyu, a legendary Siberian-born Australian light-welterweight fighter who held undisputed world titles and was arguably one of the best boxers of the modern era. His younger brother Nikita is also a boxer who turned pro a couple of years back.

With a wry look, he describes growing up in the Tszyu household as like being in a Soviet military camp. He describes his father as tough – particularly compared to what he’s like now (it appears Kostya has mellowed with age), but Tszyu insists he has a strong “respect” for his dad.

Certainly, with his father’s success, he got to see the perks of the mansions, the nice cars and the gold Rolexes, but according to Tszyu, Kostya wasn’t the type of man to give his sons an easy ride.

He recalls that when he was in year three at school, he came second in a cross-country race. He describes the reaction at home: “It was like a disgrace [that] I came second. After that, I came first every year,” he says.

“I think it was my dad setting a certain standard that you have to be different in life,” he says. “It started with him having the [signature] rat’s tail [haircut]. It wasn’t a fashion statement. It was about being different, and that’s what it symbolised – doing things differently.”

He says his father’s attitudes were, in a way, “buried in our heads”. He recalls Kostya saying, “I’m the king of the world”, something he attributes as a motivator for him.

The dichotomy in Tszyu’s childhood was the attitude of his mother, Natalia.

“I think my mum was always pushing me towards being safe in life, as in getting a degree, having a stable income, having a family,” he says.

“I guess the more I went through life, the more I realised that that’s not what I wanted. In my head, I’ve always wanted to be part of that 1%. Boxing allows me to be in that 1%.”

It appears that the only thing the fighter, who’s been described by No Limit promoter George Rose on Fox Sports as “a modern-day warrior” who “fears no man”, actually fears is mediocrity.

Boxing was obviously in his blood. He says he started in the gym “from birth – put on gloves and smacked around my grandpa”, but he did have time to play soccer as a kid. His parents wanted him to learn to work with other kids – learn teamwork.

Despite being quite good at the sport, that plan didn’t play out.

“I realised that I wasn’t meant for teams,” he bluntly puts it.

“It’s dominance, being able to dominate someone physically and mentally. I love that feeling.”

Tim Tszyu

The other plan that didn’t quite work out for Tszyu was his time at university. He describes his life to that point as fairly rigid – diet, fitness, boxing, gymnastics, soccer – no girls, no drinking, no such thing as a social life. So when he went to university to study business, for the first time, he experienced a level of freedom he hadn’t known before. His father had returned to Russia, so he got to “explore” for a year. He says his mum told him he was “a bit lost in life” at that time, but ironically, it was that experience of “normality” of what it was like to live what he describes as a “mediocre” life that made him double down on what he knew he wanted.

“My grades were shit,” he says. “I couldn’t study for shit, and I was just barely going to class.”

“I [wanted to know] how far can I go in life? And I wanted to go in deep.”

A spark lights a fire

So it was back to the gym for Tim. Firstly, he ran the business and then trained with his uncle,

Igor Goloubev.

He says when he first started sparring, he’d “smack around guys that were national champion level” even though he was unfit and had put on a bit of weight. “It was like a walk in the park,” he says.

Then, he realised that if he didn’t pursue boxing, he would be “wasting his life away”.

Before he went professional at 22 in 2016, Tszyu had built up an amateur record of more than 30 fights. His first pro bout was against Zoran Cassidy, and significantly, his father came from Russia for the fight. Tszyu says he hadn’t seen Kostya “in years” before that and was “stoked” that he came.

What followed was 24 wins in a row, 17 by way of knockout and going on to win the WBO world super welterweight championship, among a host of other accolades.

In the early days, he’d use his winnings to pay for the gym rent and try to live off the personal training money he made. He maintains the financial catalyst in his career was when he signed with No Limit Boxing around 2020 – “for me, it was a big, big deal. I was able to get a Ford Mustang in the first year – my dream car,” he says.

But his professional breakthrough moment was beating the Australian reigning number one Jeff Horn in Townsville in August of that year.

“At that time, [he was] ‘the man’ in Australia, and I guess when you take out ‘the man’, you become ‘the man’,” he says

“Either you sink, or you swim. You are either going to be going to that next level, or you’re [just] going to be a contender. This was the opportunity to establish myself as my own name, to be the world title challenger. And yeah, I guess, to slowly distinguish myself from Kostya Tszyu.”

How did he feel after the win? Ecstatic, yes, but content? No.

In a conversation with Tszyu, this is where you start to get the picture of just how driven he is.

He doesn’t appear, at this stage, to have anything that even resembles an end game.

“I thought I would be content [after that fight], and I thought, this is it. But then when I got there, I was, this ain’t it,” he says.

“I thought I’d reached the top of the mountain. And then a week or so later, I realised it was just the beginning of another one.”

Following the Horn fight, he went back-to-back against world-rated boxers, culminating in the recent bout against Fundora.

When I spoke with him, the Ortiz fight was still going to go ahead, and he was in preparation for what was going to be yet another extraordinary challenge, so I asked him what would represent the top of the mountain for him.

“[That] would be [creating] the greatest boxing family that ever lived, and that means surpassing my dad’s achievements,” he says

So where does this journey end? “It’s just an obsession right now; there’s nothing else in life that matters. It’s just me in my own world. And whoever wants to be a part of it, they can. And if you don’t, I don’t give a fuck. Simple.”

The World According to Tim Tszyu

On motivation:

“The motivation factor has always been about winning – in everything in life. If we are doing a running race, I’m coming first; if I’m playing basketball, I’m coming first. If I’m fighting, there’s no way someone else is [winning].” “After a couple of big fights, big wins, I got back home, [and] I’m like, alright, I’m onto the next target. I’m not happy. And I guess I’ve always just got new goals, just nonstop growing.”

On fighting:

“It’s dominance, being able to dominate someone physically and mentally. I love that feeling.”

Advice on how to win:

“When you do something, go all in. No backup plan. No 50/50. Think of it as a boxing fight. It’s either you or your opponent.”

Are you – or is someone you know – creating the next Afterpay or Canva? Nominations are open for Forbes Australia’s first 30 under 30 list. Entries close midnight, July 15, 2024.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.

MORE FROM FORBES AUSTRALIA