Fawn Weaver founded Uncle Nearest to honour the formerly enslaved master distiller who taught Jack Daniel the secret to making great whiskey. Seven years later, she owns the most successful Black-owned liquor empire, worth US$1.1 billion, with ambitious—and unusual—plans for the future.

IN southern Tennessee, where whiskey falls somewhere between a religion and Disneyland, Fawn Weaver looks across the 458-acre distillery–cum–amusement park that she has built in Shelbyville to support her seven-year-old brand, Uncle Nearest. There’s a history walk, four tasting areas, the world’s longest bar (518 feet), an outdoor music venue, an aging barn that was once a horse stable, a barbecue restaurant and a snack shack featuring Tennessee treats such as Mountain Dew and Goo-Goo Clusters. It’s all to compete with nearby Jack Daniel’s, which welcomes 300,000 people a year to experience whiskey in a dry county.

There’s some historical elegance going on here. Weaver, the founder and CEO, launched Uncle Nearest in honor of Nearest Green, the former slave and first master distiller of Jack Daniel’s, whose story was erased from whiskey lore for decades. She has built her company in a way that leans into all the freedoms that Green, and the generations that followed, never had.

“I don’t believe you own the brand unless you own the land. It’s special to us. But it’s also incredibly special to Black people,” says Weaver, 47, dressed in a matching red Athleta outfit. “Historically, we’ve done a lot of renting but not a lot of owning. A lot of being an ambassador and building other people’s stuff, but not a whole lot of building our own.”

And has Weaver been building. Debuting in 2017, Uncle Nearest has tripled sales since 2021, and expects $100 million in revenue this year, with 20% estimated net margins. According to reports of spirits research firm IWSR data, that makes Uncle Nearest the fastest-growing American whiskey brand in history and drives a business that Forbes conservatively estimates is worth $1.1 billion. Including real estate, Weaver’s 40% stake makes her worth $480 million, good for No. 68 on Forbes’ Richest Self-Made Women list, as well as owning the best-selling Black-owned and -led spirits brand of all time.

What’s more impressive is how she built Uncle Nearest. Weaver’s focus on ownership led her to eschew venture capital and private equity in favor of lots of individual investors—163, to be precise, for an average check of $500,000 a person—structuring deals to maintain control of the company and ownership of the land. No single outside investor owns more than 2.3%, and employees (some of whom are descendants of Nearest Green) own less than 3%. This decentralized model helps Weaver maintain control—she owns 40% of Uncle Nearest but maintains 80% of the voting rights when combined with her husband, Keith. The company also has about $106 million in bank debt.

Weaver’s ban on institutional investors didn’t scare away institutional players. With his BDT & MST merchant bank left out, billionaire Byron Trott invested personally. “Fawn consistently demonstrates exceptional leadership, long-term vision and resilience, which are all critical traits for a successful founder,” he says.

Despite Weaver’s ban—or perhaps because of it—investment bankers reach out constantly. Many spirits brands reach a level of scale and “just kind of peter out,” says Goldman Sachs’ Jason Coppersmith, a top food-and-beverage banker. Instead, Weaver builds, literally, for the long term. She has quickly become one of the largest Black landowners in Tennessee—in addition to Uncle Nearest’s location, she owns (with Keith) another 365 acres nearby. In Shelbyville, Weaver owns part of the town center, including a Georgian Revival–style building housing a U.S. Bank branch and a newspaper headquarters. With a Forbes reporter tagging along, Weaver goes to see a 379,000-square-foot former cotton mill—one of the only places in the area where Black people could find work after the Emancipation Proclamation—that’s coming on the market soon. The tour energizes her with visions of barrels aging, a bottling line and sales office space. Standing next to the realtor, Weaver agrees to buy it for $2.3 million before it’s even listed.

Weaver grew up in a strict Christian household, with a father who had been one of Motown’s original hitmakers. After moving to Los Angeles, he became a minister and couldn’t keep up with his bills. By 15, her parents pushed her to dress and live conservatively and gave her an ultimatum: Accept their rules or leave. Rather than comply, she left home with only a backpack and a lunch pail.

She dropped out of high school, lived in housing projects south of L.A. and soon found herself homeless. After stints at two shelters, Weaver says she attempted to take her own life. Twice. The second time, she recalls the sensation of the activated charcoal (used to treat overdoses) pushing through her nose and the rest of her body to rid it of the alcohol and pills she had ingested. In that moment, she decided to find her purpose.

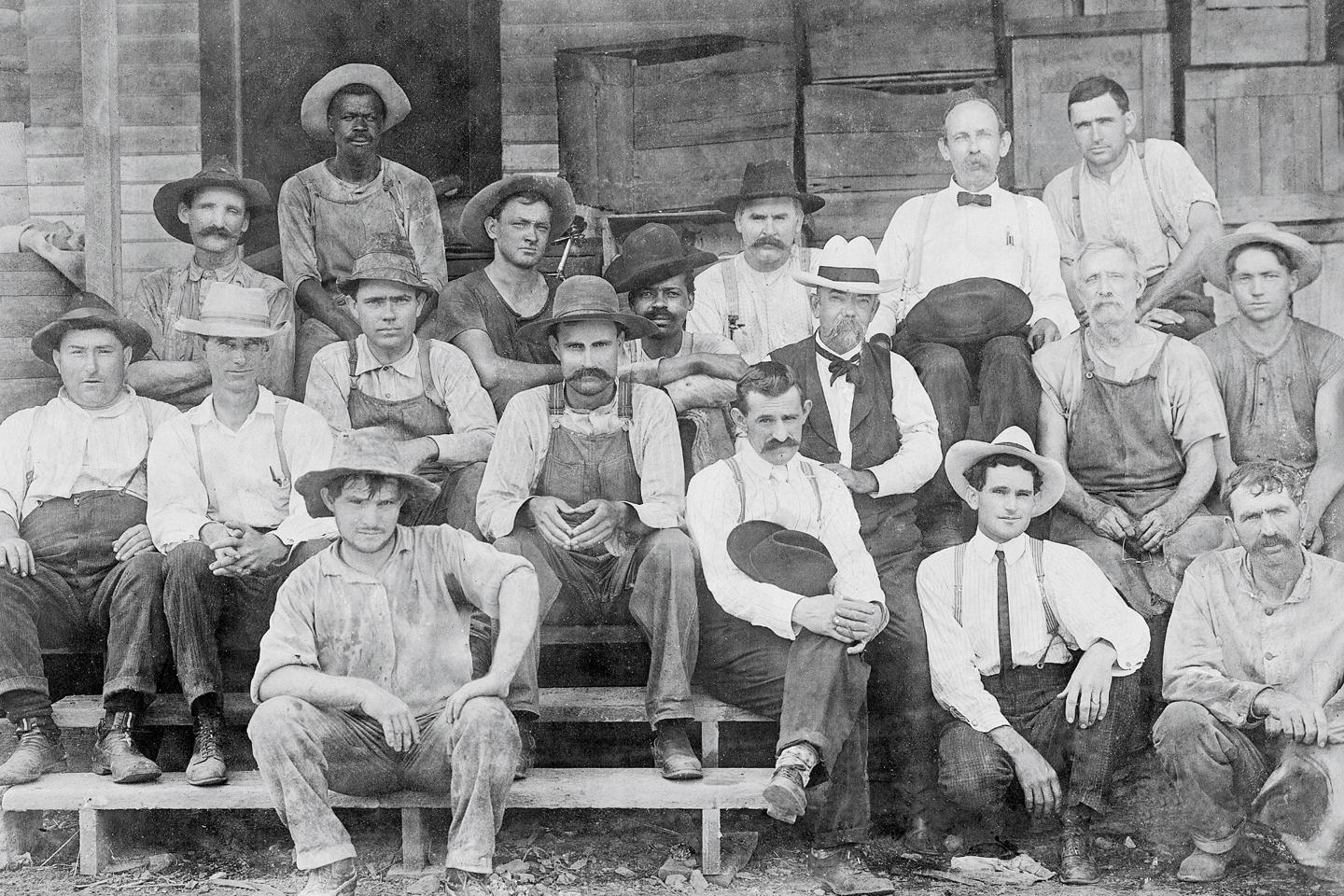

Magical History Tour: A 1904 photograph of Jack Daniel (with mustache and wearing white hat) seated next to a man believed to be George Green, a son of Nearest Green—who was Daniel’s first master distiller—inspired Weaver to create a whiskey brand in his honor.

JACK DANIEL DISTILLERY

Weaver had been working in public relations and running a special events agency, and after starting her own PR firm, it struggled due to over-hiring. Once married to Keith, who worked in California politics and then spent two decades in government affairs at Sony, she began investing with him in residential real estate around Southern California. In 2014, her book about marriage, Happy Wives Club, became a bestseller. Then, two years later, she read a story about Nearest Green in the New York Times that changed her life.

Until 1865, Green had been enslaved on a Tennessee plantation, whose farm housed and employed a young Jack Daniel. Green’s whiskey became renowned in the region, thanks to his method of using charcoal from burned trees to mellow the spirit, a practice originally developed in Africa. His bottlings were so popular that charcoal filtration became a hallmark of Tennessee whiskey, and a key differentiator from its Kentucky cousin, corn-based bourbon. Green didn’t invent the method, but he perfected it, as Weaver points out in her forthcoming book, Love & Whiskey, without formal training or the ability to read or write.

Weaver wasn’t a Jack Daniel’s drinker, but she knew there were countless former slaves whose stories, like Green’s, had been erased from history. As Green was no longer part of parent company Brown-Forman’s official history of Jack Daniel’s, Weaver sought to rectify that.

For her 40th birthday, she and Keith took a trip to Lynchburg, Tennessee, thinking she would write a book about Green. They left after making an unexpected purchase: spending $900,000 for the 300-acre farm she hadn’t realized was on the market, the same location where Green first taught Daniel how to make whiskey. Fate had one more twist: Weaver eventually found primary documents proving that the farm is the original home of Daniel’s first distillery.

As Weaver researched Green’s history—she learned that a 20-year-old Daniel had hired him to be his first master distiller after founding his eponymous distillery in 1866—she also traced his genealogy, reconnecting unknown relatives. She knew that the three descendants who still worked at Brown-Forman wanted to know why Green had been erased from tours. (The two brands now collaborate on a summit promoting Black-owned businesses.) She had already begun gobbling up trademarks, shocked that Jack Daniel’s had not secured them. And when one descendant shared the opinion that Green deserved his own whiskey, Weaver’s mission became clear.

Barrels of Success: Weaver has refined the playbook for how to build a spirits startup. She calls the strategy her “Green-book”—in honor of Nearest Green

Jamel Toppin for Forbes

To bootstrap startup costs for the distillery, the Weavers sold all their West Coast real estate, including their dream home in Old Agoura, California, and two Mini Coopers. They took their credit scores on a ride—at one point she was more than $1 million in debt—but after securing $500,000 from Keith’s former boss for the initial seed round, she got five others to invest, too. From the beginning she focused on Black investors. “The right money will find you if you’re turning down the wrong money,” she says.

The first Uncle Nearest whiskey—named 1856 for the year it is believed Green perfected charcoal filtration—debuted in 2017 and went on to win the first of more than 1,000 awards for the brand. Weaver initially focused on Oregon. As an alcohol control state (one in which the state government controls the wholesaling and retailing of spirits), it offers independents better visibility because the big distributors selling big brands like Jack Daniel’s aren’t as powerful there. She spent $1 million on marketing in the first year.

Today, there are seven Uncle Nearest releases—bourbons and ryes all produced under the direction of Victoria Eady Butler, Green’s great-great-granddaughter. “While we have a lot of work to do,” Butler says, “[Nearest’s] name is worldwide now.”

The playbook would now call for Weaver to sell. In recent years, several celebrity-backed spirits brands have changed hands for astronomical amounts, and while it feels like a bubble, the highly consolidated spirits industry relies on emerging brands, and conglomerates pay up: Diageo spent $1 billion on George Clooney’s Casamigos tequila in 2017, followed by $610 million for Ryan Reynolds’ Aviation gin in 2020. Multiples of recent spirits acquisitions are extraordinarily high—Aviation, for example, sold for an estimated 24 times revenue. In 2021, Conor McGregor’s Irish whiskey, Proper No. Twelve, was acquired for a reported $600 million, or 12 times revenue.

But Weaver insists she’s not selling. “I’ve stood my ground even when people were saying, ‘She has to have a number,’ ” she explains. “They’ve thrown every number at me and gotten the same response—no. That’s what I’m most proud of.” Instead of selling, she’s buying and launching, including vodka and, notably, cognac. More than 90% of the famed French brandy is exported each year, and more than half ships to the United States—three-quarters of which is purchased by Black Americans. “They have never had a product delivered to them that was founded by and owned by a person who looked like them,” Weaver says. “That wasn’t rocket science.”

Last October, Uncle Nearest bought Domaine Saint Martin, a 100-acre French estate built in 1669 by the Lord Mayor of Cognac, for an estimated $6 million. There’s a distillery, expansive cellars and even a cooperage where barrels are made—all ready to be transformed under Uncle Nearest. Weaver plans to buy other small spirits brands, owned by Black entrepreneurs or women, to add to the roster. So far, she has made investments in four Black-owned brands, including Equiano rum and Sorel, a Brooklyn-based liqueur.

For now, Shelbyville’s Uncle Nearest distillery remains the crown jewel in her growing empire. Last year, more than 230,000 people stopped by, making Uncle Nearest the seventh-most-visited distillery globally—and within reach of Jack Daniel’s. Those visits are also highly profitable; one $150 bottle sold directly to a visitor has a greater margin than a case sold through distributors.

Her ambition extends much further. She has 100 acres set aside to farm corn that will eventually create a small-batch whiskey. An under-construction still-house—where some of the whiskey actually gets made—will have enough capacity to produce 18,000 barrels annually. She also plans to build a hotel nearby and stage more local events, like last year’s hot air balloon festival, the first since Jack Daniel held one in the area in the early 1900s.

Equally lofty is Weaver’s goal to buy out every one of her investors so she has 100% equity. As she and Keith have no children, Weaver reveals something she has previously kept to herself: a plan to eventually bequeath the business to Nearest Green’s descendants. She’s already funding scholarships for them, with the hope that family leaders will emerge to lead the distillery’s next chapter.

“I’m going to build it large as hell. When I pass it on, I don’t want it to be a $10 billion company. I want it to be a $50 billion company,” Weaver says. “I am never going to profit on Uncle Nearest. I’ve known it from day one. I’m raising up their family.”

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.