It’s not enough for Boeing to fix the 737 Max program. To remain competitive against Airbus, the planemaker needs to make a big bet on a new jet.

The forward fuselage of a 787 at Boeing’s assembly plant in North Charleston, South Carolina.

Juliette Michel/AFP/Getty mages

To Boeing’s long list of urgent near-term problems, add one more. It needs a new airplane.

With its best-selling plane, the 737 Max, the subject of public and federal scrutiny after the terrifying midair blowout of a panel on an Alaska Airlines jet in January, the world’s largest aerospace company is struggling to recover from a nightmare that’s slashed $28 billion from its market cap. And its two decades of procrastinating the launch of another new plane program since development of the 787 formally kicked off in 2003 is increasingly looking costly. Analysts told Forbes the clock is ticking for Boeing to come up with a new narrowbody plane to stem a steep loss in market share to rival Airbus.

In November 2022, CEO David Calhoun ruled out introducing a new plane until the mid-2030s, saying the technology for a step change in fuel efficiency wouldn’t be ready till then. Critics said it was a risk-averse move that would allow Boeing to save billions in the short-term and boost investors’ returns while sabotaging its future. But Boeing is now in the midst of a management shakeup, with a new board chairman who’s aiming to hire a replacement for Calhoun before year-end. Analysts expect the next CEO to take a fresh look at developing a new airplane.

Airbus’ A320neo family has outsold the 737 Max line nearly 2 to 1, largely on the strength of the largest planes, the A321 and A321XLR. They can carry more passengers farther than the 737 Max 10, the biggest Max variant, which Boeing has yet to bring to market. Meanwhile, Airbus has a newer, more efficient small airliner, the A220, that it’s considering stretching into a larger version that would threaten the lower end of the 737 line.

“Boeing’s in the middle” between the A321 and A220 “with an aircraft that’s had trouble — not a great place to be,” Robert Spingarn, an analyst at Melius Research, told Forbes. “You’re getting to the point where your competitive edge is at risk.”

With everything that will be on the new CEO’s plate – including what promise to be difficult contract talks with Boeing’s machinists in Washington state – there’s a risk that person won’t want to touch a new airplane till the near-term problems are solved. That would be a mistake, said Spingarn.

“They should be able to do both of these things simultaneously, get the safety and quality back to where it needs to be, and at the same time figure out what the future is going to hold.”

However, analysts warn that if Boeing moves too soon, Airbus could trump it a year or two later with a plane tailored to beat it, as well as miss out on new technologies under development that promise to lower carbon emissions.

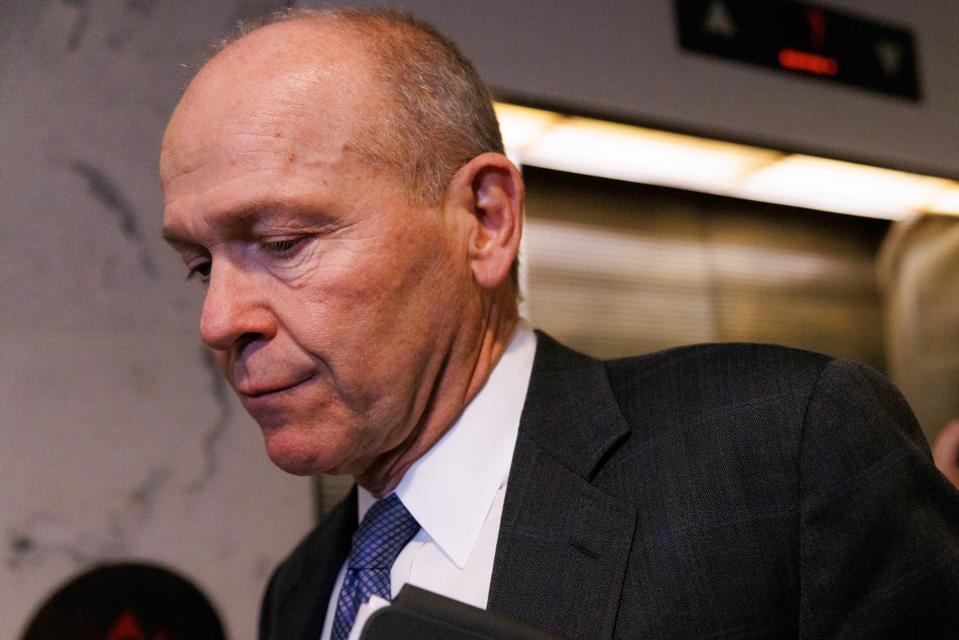

Under pressure from federal investigations and airline customers furious over delays in receiving their aircraft, Boeing’s board announced in March that it would begin searching for a new CEO to replace David Calhoun.

Aaron Schwartz/Sipa/Newscom

Failing to roll out a new plane before 2035 means Boeing’s share of the narrowbody market could slide under 40%, Ron Epstein of Bank of America has estimated.

That’s a sharp change from the previous generation of both planes, where Boeing had a roughly 52% market share – and commanded higher prices to boot, said Nick Cunningham, an analyst with equity research firm Agency Partners.

Boeing’s market share losses could be hard to reverse given the stickiness of incumbency with airlines, which are reluctant to switch plane types due to the high expense of retraining pilots to fly them, said Ken Herbert, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets.

“Calhoun … says that it’s too expensive and too risky and has given all sorts of reasons why they shouldn’t do it,” said Cunningham. “The problem is if they don’t do it, then that’s effectively a counsel of despair. It means that you’ve accepted that you are now only about a third of the narrowbody market as opposed to half the narrowbody market. And it runs a risk that you end up becoming McDonnell Douglas.” That once-proud American planemaker lost market share for decades as it limited investment to updating older models, and was bought by Boeing in 1997.

Related

Right now, even if management wanted to launch a new plane program, Boeing likely couldn’t afford to, with a cash outflow of $3.9 billion in the first quarter and expectations the bleeding will continue in the second quarter, with 737 assembly rates slowed while the company works through improvements to the manufacturing process. After that, Boeing hopes to unlock a torrent of cash by delivering by the end of the year most of the 170 Max 8s and 60 787s it had piled up in inventory as of March 31.

Airlines typically pay 65% to 70% of the purchase price of a plane on delivery. It also aims to raise 737 production to 38 per month in the second half and with a goal of 50 by 2026. But many analysts are skeptical it will come off as promised. “If there has been one thing that has been consistent about Boeing over our many years of covering the company it has been its hopelessly optimistic timetables for improvement,” Robert Stallard of Vertical Research wrote in a note. For example, Boeing had planned at the beginning of 2022 to deliver 500 737s that year. It managed 386.

Plane In Vain

Boeing has prevaricated for two decades on launching a program to replace the 737, an aircraft design that dates back to the 1960s, or to build a plane sized between the 737 and its 787 widebody.

In the early 2000s, a project called Yellowstone sketched out plans for a new narrowbody in tandem with designs that became the 787. The narrowbody would have used many of the same technologies, including a carbon fiber composite body. Boeing executives tentatively discussed bringing it to market in 2020, but those plans were up-ended in 2011 when American Airlines warned it was considering buying hundreds of an updated A320 with more efficient engines. To prevent American and other customers from defecting to Airbus, Boeing shelved the new plane and took the quicker, cheaper route of re-engining the 737, too.

The difficulties of placing a larger engine on a plane originally designed to be low to the ground to allow boarding by ladder led to the need for stability augmentation software that malfunctioned in two deadly crashes in 2018 and 2019, throwing the company into crisis.

From 2015 to 2020, Boeing also went back and forth on building a larger jet aimed at replacing the 757 and 767. When Calhoun was made CEO at the beginning of 2020, he sent designers back to the drawing board, saying the playing field had shifted. By 2021, there were reportedly plans for a smaller version to compete with the A321neo.

An artist’s depiction of the X-66A, an experimental plane under development by NASA and Boeing that could lead to a replacement for the 737. The project will test out a novel design from Boeing dubbed the Transonic Truss-Braced Wing. The long, slim wings, supported by braces that generate lift, promise to reduce fuel consumption by 10%.

NASA

Calhoun’s decision to punt on a new plane till the 2030s would give Boeing time to stabilize operations, including integrating its 737 fuselage supplier, Spirit AeroSystemsSpirit AeroSystems, which it’s in negotiations to acquire, and harvest cash from its current lineup. That includes raising production rates and bringing to market three long-delayed variants of existing planes — the Max 7, Max 10 and 777X. The company projects that will allow it to raise free cash flow to $10 billion annually by 2026, helping it pay down its net debt of roughly $40 billion – up from about $13 billion at the end of 2019.

But Cunningham thinks Boeing has quietly given itself financial headroom to invest in a new jet through the structuring of $10 billion in debt that the company raised in late April to bolster its depleted cash reserves. Despite high interest rates averaging 6.6%, Boeing has pushed out repayment for a strangely long time, he notes: about 65% of it matures from 2034 to 2064. Cunningham thinks that’s a sign the company plans to direct free cash flow to R&D. “They can build up a cash position which would enable them to develop a new airplane,” he said.

Boeing declined to respond to questions on the company’s plans, but referred Forbes to Calhoun’s statement Friday at the annual shareholders meeting that investments in its factories and R&D would increase in 2024 from nearly $5 billion the year before. “Our mission is to mature the essential technologies that will enable safe and sustainable flight in the years ahead,” he said.

Analysts expect a new plane could cost $20 billion to $30 billion in R&D and capital expenditures over eight to 10 years. If Airbus stretches the A220, Boeing might need to counter with a second, smaller plane as well, some analysts think.

A problem Boeing faces is that with Airbus in a stronger position, the European company could wait for Boeing to show its hand and then counter with something designed to top Boeing’s plane.

“The one thing they don’t want to do is go too soon and limit themselves to a certain kind of technology … and then discover that Airbus comes out with something that’s a much bigger evolutionary or revolutionary change in technology two years later,” said Spingarn. “That is largely unrecoverable and both of them are nervous about this.”

But Airbus may be forced to move faster than it would like due to greater pressure in Europe to reduce aviation’s carbon emissions, said Herbert.

It’s pledged to introduce a small, zero-emission aircraft powered by hydrogen in 2035.

It’s unclear what a new Boeing plane could look like, but one potential element it’s experimenting on with NASA is a long, thin wing mounted high on the fuselage that would be braced with diagonal struts. The lighter, more efficient wings could enable a 10% reduction in fuel burn, according to NASA. With $425 million in NASA funding, Boeing is working to mount prototypes of the truss-braced wings on an MD-90 jet for flight-testing that is scheduled to begin in 2028.

To future-proof its next plane, Boeing could develop an airframe with a conventional propulsion system to start but with the capacity to be upgraded to run on hydrogen or hybrid electric power, said Spingarn. The truss-braced wing would have plenty of room to accommodate a large open-rotor engine under development by General Electric and Safran dubbed Rise that could reduce fuel use and carbon emissions by 20%.

Boeing will likely approach airlines with two designs – a conservative one and a more radical one – and gauge interest before choosing which to go forward with.

With uncertainty about technology readiness and how Airbus could respond, Boeing faces tough decisions, but it has to embrace risks to get back on top, said Cunningham.

“It got to be the great company it was by having very bold, very competent management taking big decisions. And they unavoidably have to get back to that.”

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.