Value investors worship Warren Buffett. But his amazing investment success stems as much from his astute understanding of consumer behaviour as it does from his ability to ferret out financial bargains.

Warren Buffett is something of a national treasure. Since 1965, his Berkshire Hathaway has delivered a 19.8% compound annual return, compared to 10.2% for the S&P 500 Index, resulting in a value 140 times more than sticking with the large-cap index for 59 years. He is the world’s sixth richest person with a net worth of $133 billion—which he has pledged to give to philanthropic causes. Buffett commands instant credibility when he communicates his thoughts on investing and life, as he has generously done for his shareholders with annual letters and meetings.

Buffett earned the “Oracle of Omaha” moniker for his plainspoken explanations of stock market investing and business ownership, enterprises at which many people fail because emotions of fear and greed encroach at inopportune times. Buffett’s modus operandi has been to find a business that he likes, buy into it and hold ideally forever.

Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholder meeting last weekend was the first one for Buffett, 93, since vice chairman Charlie Munger passed away last November at the age of 99, and it was apparent that Buffett was operating in a different dynamic without his curmudgeonly sidekick who for so long complemented Buffett’s lengthy discourses with stinging quips and sagacious one-liners. Buffett clearly missed the company of his friend. At one point, after he finished answering a question about electric power generation in Utah, Buffett instinctively turned to his left and said, “Charlie?” Charlie wasn’t there. The chair was occupied by Buffett’s anointed successor, Greg Abel, chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway Energy, and vice chairman of non-insurance operations since 2018.

Forbes has been reporting on Buffett’s stock wizardry since November 1969, when we published our first profile of him, “How Omaha Beats Wall Street.” At that time, his Buffett Partnership had assets of $100 million. Today Berkshire Hathaway’s assets are more than $1 trillion.

Buffett’s overarching strategy has evolved over the years largely due to the counsel he received from Munger. Buffett started his career as a by-the-numbers Graham and Dodd bargain stock investor, but more recently his great successes have come from owning enduring franchises at reasonable prices. Berkshire Hathaway’s outsized positions in iconic companies like Coca-Cola (KO), American Express (AXP) and Apple (AAPL), as well as wholly owned companies like GEICO, have been the chief drivers of Berkshire’s six decades of investment success.

Berkshire Hathaway’s Top 10 Stocks

| Company | % Portfolio | Market Value |

| Apple (AAPL) | 43.3% | $167.1 billion |

| Bank of America (BAC) | 10.2% | $39.5 billion |

| American Express (AXP) | 9.4% | $36.3 billion |

| Coca-Cola (KO) | 6.5% | $25.1 billion |

| Chevron (CVX) | 5.4% | $20.9 billion |

| Occidental Petroleum (OXY) | 4.1% | $15.9 billion |

| Kraft Heinz (KHC) | 3.0% | $11.6 billion |

| Moody’s (MCO) | 2.6% | $9.9 billion |

| Mitsubishi (MSBHF) | 2.0% | $7.7 billion |

| Mitsui & Co. (MITSY) | 1.6% | $6.3 billion |

At this year’s annual meeting Buffett’s comments about some of his largest positions revealed just how much he uses behavioral psychology to guide many of his positions. Given his years of experience, much of it is intuitive.

Assessing overall levels of fear and greed among investors has always guided value investing at Berkshire Hathaway. In 1964, Buffett loaded up on the stock of American Express after one of the companies it was financing got caught dealing in fraudulent salad oil. Fear drove Amex’s stock down by more than 50% but it later recovered and soared as fear dissipated. Berkshire Hathaway still owns American Express shares today–more than $36 billion worth– having returned no less than 25,966% over the last 50 years. Buffett’s $5 billion investment in Goldman Sachs at the height of the 2008 financial crisis is another example of his exploiting extremes in investor behavior for profit.

Below are some edited highlights from the 2024 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting in Omaha with special attention to how behavioral psychology weighs heavily on some of his largest holdings like Apple, which now represents 43.3% of Berkshire’s $336.9 billion stock portfolio.

Buffett and Munger over the years became skilled in appraising the power of consumer preference. Buffett addressed the importance of psychology with examples of how he’s utilized those insights to make investing decisions.

Buffett: People have speculated on how I’ve decided to really put a lot of money into Apple. One thing that Charlie and I both learned a lot about was consumer behavior. That didn’t mean we thought we could run a furniture store or anything else, but we did learn a lot when we bought a furniture chain in Baltimore. We quickly realized that it was a mistake, but making that mistake made us smarter about actually thinking through what the capital allocation process would be and how people were likely to behave in the future with department stores and all kinds of things that we wouldn’t have really focused on. So, we learned something about consumer behavior from that. We didn’t learn how to run a department store.

The next one was See’s Candies, which was also a study of consumer behavior. We didn’t know how to make candy. There were all kinds of things we didn’t know, but we’ve learned more about consumer behavior as we went along. That sort of background, in a very general way, led up to the study of consumer behavior in terms of Apple’s products.

I think the psychologists call it ‘apperceptive mass.’ There is something that comes along that takes a whole bunch of observations that you’ve made, and knowledge you have, and then crystallizes your thinking into action, big action in the case of Apple. I guess my mind reached apperceptive mass, which I really don’t know anything about, but I know the phenomenon when I experience it.

Maybe I’ve used this example before, but if you talk to most people, if they have an iPhone and they have a second car, the second car cost them $30,000 or $35,000, and they were told that they could never have the iPhone again, or they could never have the second car again, they will give up the second car. Now, people don’t think about their purchases that way, but I think about their behavior, and so we just decide without knowing.

I don’t know. There may be some little guy inside the iPhone or something. I have no idea how it works, but I know what it means. I know what it means to people, and I know how they use it, and I think I know enough about consumer behavior to know that it’s one of the great products, maybe the greatest product of all time, and the value it offers is incredible.

I actually saw it with GEICO when I went there in 1950. I didn’t know exactly what I was seeing, but (GEICO CEO) Lorimer Davidson on a Saturday, in four hours, taught me enough about what auto insurance was. I knew what a car was, and I knew what went through people’s minds. I knew they didn’t like to buy it, but I knew they couldn’t drive without it, so that was pretty interesting. Then he filled in all the blanks in my mind as I sat there on that Saturday afternoon. If you can offer somebody a good product, cheaper than the other guy, and everybody has to buy it, and it’s a big business, it’s very attractive to be in.

No company hardly does business around the world like Coca-Cola. I mean, they are the preferred soft drink in something like 170 or 180 out of 200 countries. Those are rough approximations from a few years back, but that degree of acceptance worldwide is extraordinary.

CNBC’s Becky Quick noted that Berkshire’s recent quarterly report showed that it had sold 115 million shares of Apple. Quick then conveyed this question from a 27-year-old Malaysian shareholder: “Last year you mentioned Coca-Cola and American Express being Berkshire’s two long-duration partial ownership positions, and you spent some time talking about the virtues of both these wonderful businesses. In your recent shareholder letter, I noticed that you have excluded Apple from this group of businesses. Have you or your investment manager’s views of the economics of Apple’s business or its attractiveness as an investment changed since Berkshire first invested in 2016?”

Buffett: No, but we have sold shares, and I would say that at the end of the year, I would think it extremely likely that Apple will be the largest common stock holding we have now. Charlie and I looked at common stocks as businesses, so when we own a Dairy Queen or whatever it may be, we look at that as a business. When we own Coca-Cola or American Express, we look at them as businesses.

Now, there are differences in taxes and a whole bunch of things, but in terms of deploying your money, we always look at every stock as a business, and we have no way and there is no attempt made to predict markets.

I got interested in stocks very early, and I was fascinated by them. I wasn’t wasting my time, because I was reading every book possible and everything else. Finally, I picked up a copy of the Intelligent Investor in Lincoln (Nebraska), and it said, much more eloquently than I can say it: If you look at stocks as a business and treat the market as something that isn’t there to instruct you, but it’s there to serve you, you’ll do a lot better over time than if you try to take charts and listen to people talk about moving averages and look at the pronouncements and all that sort of thing. That made a lot of sense to me then, and it’s changed over the years, but the basic principle was laid out by Ben Graham in that book, which I picked up for a couple of dollars. Then Charlie came along and told me how to put it to even better use, and that’s sort of the story of why we own American Express, which is a wonderful business. We own Coca-Cola, which is a wonderful business, and we own Apple, which is an even better business.

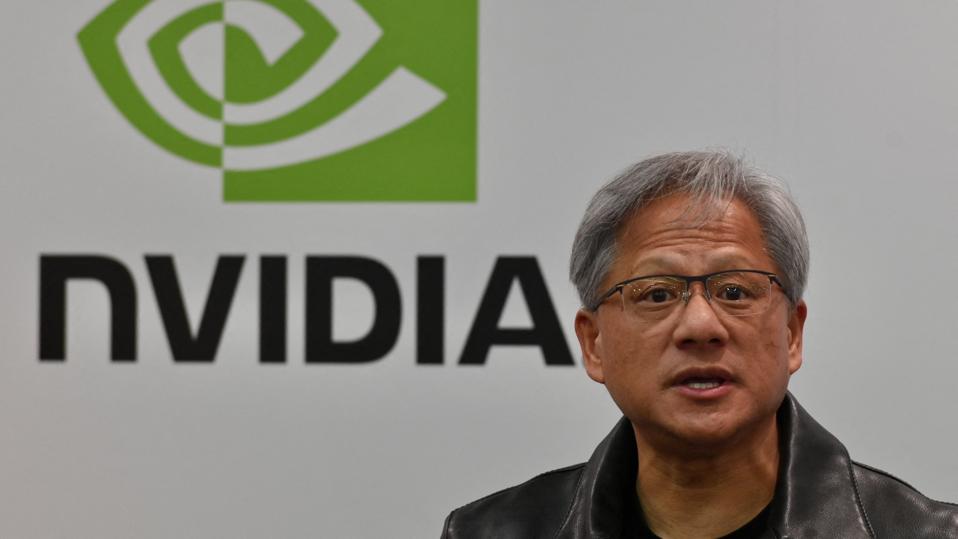

Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren E. Buffett

Photo by Tmothy Archibald for Forbes

Unless something really extraordinary happens, we will own Apple and American Express and Coca-Cola when (Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman) Greg (Abel) takes over this place. We will have Apple as our largest investment, but I don’t mind at all, under current conditions, building the cash position. I think when I look at the alternative of what’s available, the equity markets, and I look at the composition of what’s going on in the world, we find it quite attractive.

Buffett added that part of the motivation for trimming Berkshire’s Apple holdings was what he views as historically low corporate tax rates.

Buffett: Almost everybody I know pays a lot of attention to not paying taxes, and I think they should, but we don’t mind paying taxes at Berkshire, and we are paying a 21% federal rate on the gains we’re taking in Apple. That rate was 35% not that long ago, and it’s been 52% in the past when I’ve been operating. The federal government owns a part of the earnings of the business we make. They don’t own the assets, but they own a percentage of the earnings, and they can change that percentage any year. The percentage that they’ve decreed currently is 21%.

I would say with present fiscal policies that something has to give, and I think that higher taxes are quite likely. If the government wants to take a greater share of your income, or mine or Berkshire’s, they can do it, and they may decide someday that they don’t want the fiscal deficit to be this large—because that has some important consequences, and they may not want to decrease spending a lot—and they may decide they’ll take a larger percentage of what we earn and we’ll pay it.

We always hope at Berkshire to pay substantial federal income taxes. We think it’s appropriate. If we send in a check like we did last year, we sent more than $5 billion to the U.S. federal government, and if 800 other companies had done the same thing, no other person in the United States would have had to pay a dime of federal taxes, whether income taxes, no Social Security taxes, no estate taxes. It doesn’t bother me in the least to write that check. I really hope, with all America has done for all of you, that it shouldn’t bother you that we do it, and if I’m doing it at 21% this year and we’re doing it at a higher percentage later on, I don’t think you’ll actually mind the fact that we sold a little Apple this year.

Berkshire Hathaway holds $189 billion in cash and short-term securities that could be invested in stocks. Buffett was asked why he has not been deploying his massive heap of available capital into equity purchases.

Buffett: I don’t think anybody sitting at this table has any idea of how to use it effectively and, therefore, we don’t use it. We don’t use it now at 5.4% (short-term Treasury rates), but we wouldn’t use it if it was at 1%. Don’t tell the Federal Reserve that.

We only swing at pitches we like. It’s true that in someplace like Japan, if the company had had a $30 billion or $40 billion business, we’d have had great returns on equity. If I saw one of those now, I’d do it for Berkshire. It isn’t like I’ve gone on a hunger strike or there’s something like that going on. It’s just that things aren’t attractive. There are certain ways that can change, and we’ll see whether they do.

China’s stock market has been in contraction. Over the past three years, the FTSE China 50 Index has returned -36%. Buffett was asked about his appetite for investing in companies based in China and Hong Kong, and he affirmed his belief that U.S. companies provide plenty of international exposure.

Buffett: Our primary investments will always be in the United States. American Express does business around the world, and no company does business around the world like Coca-Cola. Its degree of acceptance worldwide is, I think, almost unmatched.

We made a commitment in Japan five years ago, and that was just extraordinarily compelling. [In 2020 Berkshire revealed that it owned stakes in 5 large Japanese trading firms Sumitomo, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, and Marubeni.] We bought it as fast as we could. We spent a year, and we got a few percent of our assets in five very big companies, but you won’t find us making a lot of investments outside the United States, although we’re participating through these other companies in the world economy.

I understand the United States rules, weaknesses, strengths, whatever it may be. I don’t have the same feeling for economies generally around the world. I don’t pick up on other cultures extremely well, and the lucky thing is, I don’t have to, because I don’t live in some tiny little country that just doesn’t have a big economy. I’m in an economy already that, after starting out with half a percent of the world’s population, has ended up with well over 20% of the world’s output in an amazingly short period of time.

We will be American-oriented. If we do something really big, it’s extremely likely to be in the United States. I’m aware of what goes on in most markets, but I think it’s unlikely that we make any large commitments in almost any country you can name, although we don’t rule it out entirely. I feel extremely good about our Japanese position, but we feel that we’re very less likely to make any truly major mistakes in the United States than in many other countries.

Buffett was asked about how the emergence of generative artificial intelligence will impact the investment world and human life overall. He compared AI to the development of the atomic bomb.

Buffett: I don’t know anything about AI, but that doesn’t mean I deny its existence or importance or anything of the sort. Last year, I said that we let a genie out of the bottle when we developed nuclear weapons, and that genie has been doing some terrible things lately. The power of that genie is what scares the hell out of me, and then I don’t know any way to get the genie back in the bottle. AI is somewhat similar.

It’s part way out of the bottle, and it’s enormously important, and it’s going to be done by somebody. We may wish we’d never seen that genie, or that it may do wonderful things. I’m certainly not the person who can evaluate that, and I probably wouldn’t have been the person who could have evaluated it during World War II when we tested a 20,000-ton bomb that we felt was absolutely necessary for the United States and would actually save lives in the long run. We also had Edmund Teller, I think it was, on a parallel with Einstein, saying with this test, you may ignite the atmosphere in such a way that civilization doesn’t continue. We decided to let the genie out of the bottle, and it accomplished the immediate objective, but whether it’s going to change the future of society, we will find out later.

Now, AI, I had one experience that does make me a little nervous. Fairly recently, I saw an image in front of my eyes on the screen, and it was me and it was my voice and wearing the kind of clothes I wear, and my wife or my daughter wouldn’t have been able to detect any difference, but it was delivering a message that in no way came from me. So when you think of the potential for scamming people, if you can reproduce images that I can’t even tell, that say, I need money, you know, it’s your daughter, I’ve just had a car crash, I need $50,000 wired, scamming has always been part of the American scene, but this would make me interested, if I was interested in investing in scamming. It’s going to be the growth industry of all time. Obviously, AI has potential for good things, too, but I don’t have any advice on how the world handles it because I don’t think we know how to handle what we did with the nuclear genie. I do think, as someone who doesn’t understand a damn thing about it, that it has enormous potential for good and enormous potential for harm. I just don’t know how that plays out.

The one moment when Buffett looked most like he may have been choking back emotion was when a young shareholder asked, “If you had one more day with Charlie, what would you do with him?”

Buffett: Well, it’s kind of interesting because, in effect, I did have one more day. I mean, it wasn’t a full day or anything, but we always lived in a way where we were happy with what we were doing every day. I mean, Charlie liked learning. He liked a wide variety of things, so he was much broader than I was, but I didn’t have any great desire to be as broad as he was, and he didn’t have any great desire to be as narrow as I.

We had a lot of fun doing anything, you know, we played golf together, we played tennis together, we did everything together. This you may find kind of interesting. We had as much fun, perhaps even more to some extent, with things that failed, because then we really had to work and work our way out of them. In a sense, there’s more fun having somebody that’s your partner in digging your way out of a foxhole than there is just sitting there and watching an idea that you got ten years ago just continually produce more and more profits.

He really fooled me, though. He went to 99.9 years. I mean, if you pick two guys, you know, he publicly said he never did a day of exercise except when it was required when he was in the army. He never did a day of voluntary exercise. He never thought about what he ate. Charlie was interested in more things than I was, but we never had any doubts about the other person, period. So, if I’d had another day with him, we’d probably have done the same thing we were doing in earlier days, and we wouldn’t have wanted another.

There’s a great advantage in not knowing when you’re going, what day you’re going to die, and Charlie always said, just tell me where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there. Well, the truth is he went everywhere with his mind, and therefore he was not only interested in the world at 99, but the world was interested in him. They all wanted to meet Charlie, and Charlie was happy to talk with them. The only person I could think of like that was the Dalai Lama. I don’t know that they had a lot else in common, but Charlie lived his life the way he wanted to, and he got to say what he wanted to say. He loved having a podium.

I can’t remember any time that he was mad at me, or I was mad at him. It just didn’t happen. Calling him was fun back when long distance rates were high, and we used to talk daily for long periods. We did keep learning and we liked learning together, but, you know, we tended to be a little smarter because, as the years went by, we had our mistakes and other things where we learned something. The fact that he and I were on the same wavelength in that respect meant that the world was still a very interesting place to us when he got to be 99, and I got to be 93.

Sometimes people would say to me or Charlie at one of these meetings, if you could only have lunch with one person that lived over the last 2,000 or so years, who would you want to have it with? Charlie says, I’ve already met all of them, because he read all the books. I mean, he eliminated all the trouble of going to restaurants to meet them. He just went through a book and met Ben Franklin. He didn’t have to go have lunch with him or anything of the sort.

It’s an interesting question. What you should probably ask yourself is who do you feel that you’d want to start spending the last day of your life with, and then figure out a way to start meeting them, or do it tomorrow, and meet them as often as you can, because why wait until the last day? And don’t bother with the others.

Buffett has created staggering sums of wealth not only for himself, but also for thousands of Berkshire Hathaway shareholders. Buffett has pledged that he will leave his riches to charity, and he has enabled Berkshire investors to make large endowments to favored causes. A short film profiled how Dr. Ruth Gottesman redeemed $1 billion in Berkshire stock to make the Albert Einstein College of Medicine tuition-free in perpetuity.

Buffett: She may have more zeroes, but she’s the prototype of a good many Berkshire Hathaway shareholders. Ruth Gottesman gave $1 billion to Albert Einstein to take care of all of us, and that’s why Charlie and I have had such fun running Berkshire.

There are all kinds of wealthy public companies throughout America, and there are certainly cases where in one family, somebody has made a very large amount of money and is devoting it to philanthropy, or much of it to philanthropy, such as the Walton family in Walmart, and certainly Bill Gates did the same thing at Microsoft. What is unusual about Berkshire is the very significant number of Berkshire shareholders all over the United States who have contributed $100 million or more to their local charities, usually with people not knowing about it. I think it’s many multiples of any other public company in the country.

I don’t think you’ll find any company where a group of shareholders who aren’t related to each other have done something along the lines of what Ruth did a few weeks ago, just to exchange a little piece of paper that they’ve held for five decades, and they’ve lived well themselves. They haven’t denied their family anything, but they don’t feel that they have to create a dynasty or anything, and they give it back to society, and a great many do it anonymously. They do it in many states.

We have had a very significant number of people, and there’s more to come. Obviously, they had to be people who came in early, or their parents did, or their grandparents did, but they’ve all lived good lives. They haven’t denied themselves anything. They have second homes, and people knew them in the community, but they’ve used what they accomplished and what they saved. They denied themselves consumption. That’s what savings are, consumption deferred.

It sort of restores your faith in humanity, that people defer their own consumption within a family for decades and decades, and then they could do something, and they will. I think it may end up being 150 people to pursue different lives and talented people and diverse people to become a dream of being a doctor and not have to incur incredible debt to do it, or whatever may be the case. You’re a unique group of shareholders among public companies, as far as I know, in terms of the way you’ve deferred your own consumption while living fine to help other people. It takes a lot of years, but it can really amount to something very substantial. What Ruth did was look at a little piece of paper that actually was a claim check on the output of others in the future. She said instead of the output being for her, the output would be for a continuing stream of people, for decades and decades and decades to come.

Thank you very, very much for coming, and I not only hope that you come next year, but I hope I come next year.

John Dobosz is editor of Forbes Dividend Investor, Forbes Billionaire Investor and Forbes Premium Income Report. This story was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.