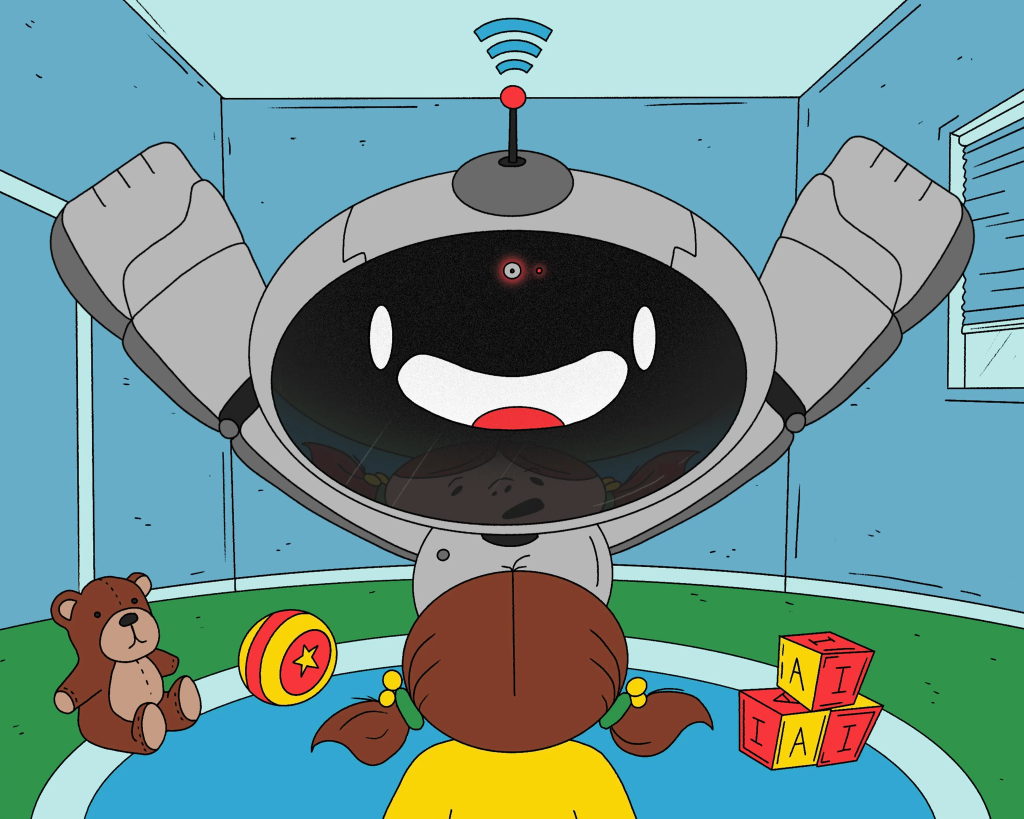

A host of startups are building robots and stuffed toys that can have full-fledged conversations with children, thanks to generative AI.

Six-year-old Sophia Valentina sits under a decorated Christmas tree as she unwraps her present: a tiny lavender-colored generative AI robot, whose face is a display and whose body is embedded with a speaker. “Hey Miko,” Sophia says, and the gadget lights up with round eyes and blue eyebrows.

In early December, Sara Galvan bought Miko Mini, a $99 robotic companion embedded with in-house AI models as well as OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, with the hopes that it would help homeschool her daughters.

Over the last month, Sophia has used Miko to solve math problems, listen to princess stories and ask questions like “how is Christmas celebrated,” Galvan said.

“They begin to learn self-guided learning, which is huge for us with homeschool and helps expand their curiosity and their minds,” she said.

Miko, which can also play games like hide and seek, is part of a growing group of pricey GPT-powered robots rolling into the toy market.

Some AI toys are touted as a screen-free form of entertainment that can engage children in conversations and playful learning, like Grok, a $99 AI plushie that can answer general questions (not to be confused with Elon Musk’s ChatGPT competitor Grok, though the toy Grok is voiced by his former girlfriend Grimes).

Others claim to offer additional features beyond storytelling and learning activities. There’s Fawn, a $199 cuddly baby deer intended to provide emotional support, and Moxie, a $799 turquoise-colored robot that can recite affirmations and conduct mindfulness exercises.

These robotic pals are designed to not only help children grow academically and improve communication skills but also teach them how to deal with their emotions during times of distress.

Fostering social and emotional well-being is one of Miko’s intended functions, said CEO and cofounder Sneh Vaswani, who participated in several international robotics competitions before starting his company in 2015 and launching the first iteration of AI companion Miko in 2017.

“Our goal is to help parents raise kids in the modern world by engaging, educating and entertaining children through multimodal interactions with robotics and AI,” he told Forbes.

Vaswani has sold almost 500,000 devices to date across more than 100 countries and expects to cross $50 million in revenue in the fiscal year ending in March 2024, he told Forbes.

His Mumbai-based startup has raised more than $50 million and was last valued at about $290 million, according to Pitchbook.

Miko is trained on data curated from school curriculum, books and content from partners like Oxford University Press and is built using proprietary technology including facial and voice recognition, recommendation algorithms and a natural language processing layer, Vaswani said.

The bot is programmed to detect different accents and provide educational content catered to the geographic region where it’s sold. The company has also teamed up with media giants like Disney and Paramount, allowing them to publish their content on Miko.

“There could be a storytelling app from Disney or a Ninja Turtles app from Paramount,” he told Forbes, adding, “It’s like a Netflix plus an iPhone on wheels given to a child.”

Other toys were built out of a desire to bring fictional characters to life.

Misha Sallee and Sam Eaton, the cofounders of startup Curio Interactive — and the creators of Grok — were inspired to create the rocket-shaped AI plushie thanks to fond childhood memories of watching movies like Toy Story.

But making toys speak intelligently was a far-fetched idea until ChatGPT came out, Sallee said. Grok is built on a variety of large language models that help it act like a talkative playmate and an encyclopedia for children.

Canadian musician Grimes invested in the startup and voiced the characters, which are a part of what Sallee calls a “character universe.”

“As a mother, it resonated with her. It was something that she wanted to lean in and collaborate on,” Sallee said. “She wanted a screen-free experience for her kids and for kids around the world.” (Grimes did not respond to a request for comment.)

“It’s like a Netflix plus an iPhone on wheels given to a child.”

Sneh Vaswani, CEO and cofounder of Miko

Another plush AI toy is Fawn, a baby deer programmed with OpenAI’s large language model GPT-3.5 Turbo and text-to-speech AI from synthetic speech startup ElevenLabs.

Launched in July 2023 by husband and wife duo Peter Fitzpatrick and Robyn Campbell, Fawn was designed to help children learn about and process their emotions while maintaining the tone and personality of an eight-year-old.

Still in its early stages, the startup plans to ship its first orders before the end of March 2024.

“[Fawn] is very much like a cartoon character come to life,” said Campbell, who previously worked as a screenwriter at The LEGO Group. “We’ve created this character that has feelings, likes and dislikes that the child relates to.”

While generative AI is capable of spinning up make-believe characters and content, it tends to conjure inaccurate responses to factual questions. ChatGPT, for instance, struggles with simple math problems — and some of these AI toys have the same weakness.

For instance, in a recent video review of generative AI-powered robot Moxie, it incorrectly said 100 times 100 is 10.

Paolo Pirjanian, CEO and founder of Embodied, Inc., the company behind Moxie, said that a “tutor mode” feature was announced in early January and will be available in the robots later this year.

“Academic questions — paired with environmental factors like multiple speakers or background noise — can sometimes cause Moxie’s AI to need further prompting,” Pirjanian said.

“If… the model invents an answer that’s not correct, that can create a serious misconception and these misconceptions are much harder to correct,” said Stefania Druga, a researcher at the Center for Applied AI at the University of Chicago.

In Fawn’s case, Campbell said the AI model has been stress tested to prevent it from veering into inappropriate topics of conversation. But, if the model makes up information, it’s often a desired outcome, Campbell said.

“[Fawn] is not designed to be an educational toy. She’s designed to be a friend who can tell you an elaborate story about a platypus. Her hallucinations are actually not a bug. They’re a feature,” she said.

The case for therapy

For Moxie, the stakes are higher than other AI toys because it’s being marketed as a tool for social and emotional development. In 2021, Kristen Walmsley bought the robot on sale for $700 for her 10-year-old son, Oliver Keller who has an intellectual disability and ADHD.

“We were really struggling with my son, and I was really desperate to find something that could help him. I bought it because it was advertised as a therapeutic device,” Walmsley tells Forbes.

Walmsley said that Oliver, who at first found the robot “creepy” and eventually warmed up to it, now uses it to share his feelings and recite positive affirmations.

In one instance, when Oliver was overwhelmed and said he was feeling sad, the robot, which was already active and listening to the conversation, chimed in.

“Sometimes I have to remind myself that I deserve to be happy. Please repeat this back to me: ‘I deserve to be happy,’” Moxie said.

In another instance, Moxie and Oliver had a conversation about embarrassment and Moxie replied with affirmations about being confident.

“It was impressive to see that it could do that because my son really struggles with low self esteem,” Walmsley said, adding that her son has repeated these affirmations to himself even when the robot is not around.

Moxie’s latest version is embedded with large language models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 and GPT-3.5.

Pirjanian claims that the robot can conduct conversations that are modeled after cognitive behavior therapy sessions, which can help children identify and speak about their source of anxiety or stress, and offer mindfulness exercises.

Valued at $135 million, the Pasadena-based startup has raised $80 million in total funding from entities like Sony, Toyota Ventures, Intel Capital and Amazon Alexa Fund.

“We have this thing called animal breathing where Moxie will breathe like different kinds of animals just to make it fun for children,” he said.

Miko, whose screen can be used to receive video calls through a parent app, will also offer a therapeutic experience for kids. Vaswani told Forbes that he plans to introduce a new feature that would allow human therapists to conduct teletherapy on the robot’s screen.

Parents would have to grant access to the therapist to access Miko.

As of now, the tiny generative AI robot isn’t suited for emotional support.

In a Youtube review of the robot, Sasha Shtern, the CEO of Goally, a company that builds devices for children with ADHD and autism, tells Miko “I am nervous.” The robot responds “It’s okay to feel nervous about medical procedures but doctors and nurses are there to help you.”

Miko spoke about medical procedures even though Shtern never mentioned anything related to that.

“It was like talking to an adult who’s watching a football game and heard half my question,” Shtern said in the video.

And Fawn can coach a child about how to talk about stressful situations (like getting bullied in school) with an adult without feeling embarrassed, Campbell said.

She told Forbes that Fawn’s conversational AI has been fine-tuned with scripts she wrote based on child development frameworks derived from books like Brain Rules for Baby and peer reviewed research.

The duo also consulted an expert in child development while developing their product.

“[Fawn’s] hallucinations are actually not a bug. They’re a feature.”

Robyn Campbell, cofounder at Fawn Friends

Moxie’s potential as a replacement for expensive therapists is part of the reason why the almost $800 robot is priced much higher than its competitors, Pirjanian said.

He said the steep price is largely due to everything under the hood: a camera and sensors to detect and analyze facial expressions, a mechanical body that moves depending on the mood of the conversation and algorithms that screen out any harmful and inappropriate responses from the generative AI.

“The technology that’s in Moxie is more costly than what you find in an iPhone,” he said.

However, experts say generative AI has not yet reached a stage where it can be safely used for crucial tasks like therapy.

“Providing therapy to a vulnerable population like kids or elders is very difficult to do for a human who specializes in this domain,” Druga told Forbes. “Delegating that responsibility to a system that we cannot fully understand or control is irresponsible.”

Then, there’s the privacy question. Other, less advanced versions of these toys haven’t had strong security measures to protect children’s data.

For instance, Mattel’s Hello Barbie toy, an AI-powered doll that could tell jokes and sing songs, was deemed a “privacy nightmare” because hackers could easily access the recordings of children.

Another doll, My Friend Cayla, raised alarms among privacy experts who found that it could be hacked via Bluetooth and could be used to send voice messages directly to children.

Newer startups have implemented guardrails to protect data privacy. Pirjanian said Moxie’s visual data is processed and stored on the device locally instead of the cloud.

Transcripts of conversations are stripped of personally identifiable information and encrypted in the cloud before being used to retrain the AI model. Similarly, at Miko, children’s data is processed on the device itself.

Hey Curio cofounder Sallee said that he and his team “take privacy seriously” and that its toys are compliant with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA). Fawn Friends does not record or store any data itself but is subject to OpenAI’s privacy policy, cofounder Fitzpatrick said.

Despite these precautions, some parents like Walmsley are concerned about their personal data leaking.

Moxie has large round green eyes that follow a person around a room, she said, and the fact that it has a camera that can record everything happening in a room and her child’s emotional responses, makes her “a little uncomfortable.”

But, she still thinks the generative AI could be a valuable tool for parents with special needs children.

“Seeing it come alive and actually help him regulate his emotions has made it worth every penny,” she said. “It’s done more than some of the therapies that we’ve tried for him.”

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.