How RØDE beat off an attack by a Chinese drone company and how a lack of workers sent another high-tech manufacturer offshore

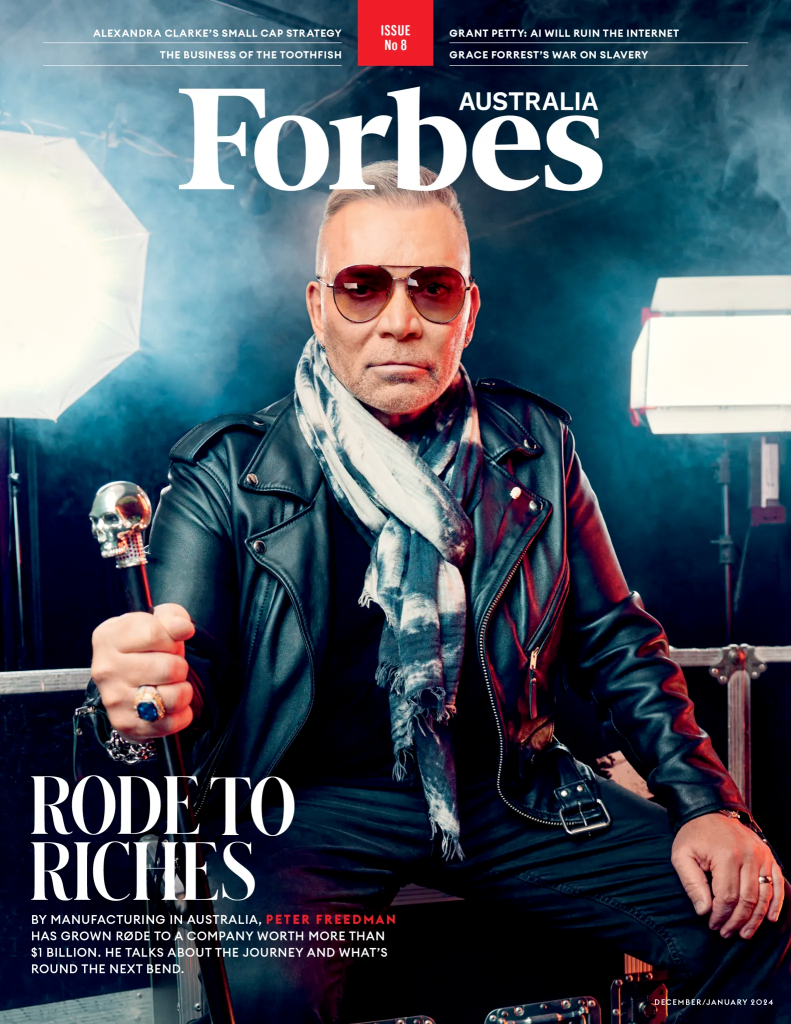

Peter Freedman, founder and owner of RØDE Microphones, was worried. DJI, a Chinese government-backed drone company, was diversifying into video and sound and had come out with a new wireless microphone early this year, threatening to eat the Australian mic’s lunch.

Freedman takes such assaults personally, says RØDE CEO Damien Wilson. He’s not necessarily cool, calm and collected. And it hurt to admit, but the DJI mic did a few things better than RØDE’s equivalent. At $510, it threatened the world dominance of RØDE’s best-selling product, the Wireless Go – two wireless lapel mics feeding back to a camera-mounted receiver. They needed to defend their position. Hard.

“We knew what the market was asking for and which DJI had implemented,” recalls RØDE Microphones’ chief of staff, Scott Emerton. “But we also had other ideas to create an even higher-end, more premium product.”

Issue Eight of Forbes Australia is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

Freedman decided they’d keep the existing Wireless Go, drop its price, and design and manufacture a new product – the Wireless Pro – with a few world firsts. But it needed a new design and tooling, and he needed it yesterday.

The staff observe that Freedman goes through all five stages of grief when his primacy in the market faces such a challenge. “He’s upset that someone’s cut our lunch. He’ll squarely blame the business for not being innovative enough to see it coming,” says Wilson. “But then, when we gather together as a group of product managers, engineers and marketers and come out with something better, he’s elated.”

Speed was crucial, says Emerton. “If you talk to another company and say, ‘Hey, we want to go from concept to in-market in 12 months, they’ll laugh at you. Eighteen months, maybe. Two years, probably. We did it in 100 business days.”

RØDE added $200 worth of improvements to the new mic, took a deep breath, and put it on the market for $599. “Because we make everything here, we’re able to play with those margins and say, ‘Nah, we can take a bath on the microphones and make it back on the wireless kits and whatever,’” says Emerton.

Related

Making everything in-house, in Australia, is the secret, says Freedman. “I just walk across the road and talk to the engineers. Two days later, we’re making it. If I was relying on an overseas

supplier, you place the order, they gear it up, they make it and ship it. Three months later, you can see the first sample. And the price is higher. They’ve got you. What will you do if they put their price up 15%? Nothing. And if there’s a fault with it, there’s a big discussion of whose problem it is. Forget it.”

While there’s a commonly held belief that Australia no longer makes stuff beyond lattes and McMansions, Freedman’s RØDE is an example of a manufacturing sector thriving in Australia. The Australian Bureau of Statistics says 930,000 Australians are still employed in manufacturing – up 100,000 in the past five years.

But the number is actually 1.3 million according to Tyson Bowen from the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre. If you count all the people at the front and back ends of the manufacturing process, the number employed directly by manufacturers is roughly equivalent to the construction industry – and more than six times larger than the 200,000 in mining.

But finding the right people is hard. Blackmagic Design started manufacturing all its video editing gear in Australia but stumbled when it needed to ramp up production in the first decade of this century. “We couldn’t find the people to run a second shift competently,” says Blackmagic CEO and co-founder Grant Petty. “So, we went to Singapore for the management talent.”

The shortage of manufacturing skills resulted from a “40-year experiment by both sides of politics to have no industrial base”, he said. Blackmagic still manufactures its larger products in Australia, and Petty has no intention of exiting the country. “I think it’s always good to have some manufacturing near engineering because engineering needs to see how manufacturing works.”

In 2016, he opened a third plant 50km from Singapore on the Indonesian island of Batam for the cheaper space and proximity to Singapore’s manufacturing talent. “Whereas we just didn’t have any skill in Australia. Australians can’t manufacture anymore.”

Blackmagic still manufactures in Melbourne. “But it’s insanely hard to run because every supplier is trying to desperately overcharge for everything,” says Petty.

He blames Gillard government industrial reforms and pay rises for hastening his move offshore. (Gillard oversaw a rise in super from 9% to 12% to be introduced over seven years, and while she was prime minister, in 2012, the Fair Work Commission lifted the minimum wage by $17 a week.)

“I remember thinking, ‘Lucky we have the factory overseas,’ because we suddenly had this massive increase in costs. We moved most of the product out, apart from physically large products that were complex and needed to be close to engineering. Film scanners and things like that.

“We sell 1.5% of our products in Australia and probably build two or three products here out of 400 to 500 models. The audio console, the big DaVinci panel and the film scanner. They’re significant products but they’re physically big and they ship out as individual products.”

Freedman also struggled to find people for RØDE. Luke Hamilton, RØDE’s head of technical manufacturing, says a generation of toolmakers was missing. “There are a few old guys [at RØDE] from the last bastions of toolmaking in Sydney that shut down. We captured them. They’re sharing their skills with the apprentices.”

Part of RØDE’s success has been of those toolmakers to make the tools that make its parts. Such capacity enables Freedman to boast he could produce a toothbrush or a jet engine at his Silverwater factory.

Hamilton points to an empty spot on the floor. A $1.1 million machine that will fill the space is en route from Japan. It is accurate to a millionth of a millimetre. “It can move a distance less than the width of the coronavirus,” Hamilton says.

“Nobody in the audio game has production like this,” says Freedman. “Our competitors can’t believe that we can sell products – with great profit – that are super-high quality for half what they’re doing because they have to pay somebody else for the parts.”

Humans only touch each product for seconds. “If we were handmaking stuff, we’d be in trouble. But we don’t handmake stuff. Even with the iPhone in China, they still pick them up and do things with them – we don’t.

“Electricity is not that expensive, and we’re all paying the same for the plastic pellets used for making high-end polymer. Freight out of here is cheap. We’re cheaper and better than China, which blows people away. But it’s a fact.

“I’ve got half a billion invested here. Never mind that I’ve got the engineers who know how to run it, who’ve learnt those skills over 30 years. You can’t turn it on tomorrow. Nobody will take me on in audio because if you’ve got that kind of money, go and buy an office building and sit back and do nothing. This is my fortress.”

Making it

- 47,000 Australian businesses are manufacturers.

- They account for about 10% of GDP.

- 90% of them employ 20 people or less.

- 5% of them make up 95% of manufacturing exports.