Space Machines Company launched in 2019 with a mission to clean up space junk and service some 7,000 satellites orbiting in the sky. After two-and-a-half years in design-mode, its orbital servicing vehicle, Optimus, is ready for take-off, on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launch in March 2024.

Rajat Kulshrestha and George Freney have been mates for a long time, first joining forces in 2014 to build out a retail-tech company called Booodl, which they eventually shut down in 2017.

That wouldn’t be their last venture, with the pair going on to launch Space Machines Company, ans the story goes like this: Freney, a serial entrepreneur from Adelaide, got a call from Kulshrestha a couple of years after they parted ways.

“Look, George, I’ve got an idea,” Kulshrestha said. This is gonna be good, Freney thought.

“I think we should start thinking about space. What about we build an autonomous in-space servicing capability?” Kulshrestha posed.

“I reckon that sounds pretty bold and ambitious and interesting,” Freney replied. And that was the start of that.

Kulshrestha, an aerospace engineer, had been busying himself in the US and Australia in various chief tech and chief commercial officer roles, before launching Space Machines Company in 2019 with Freney, with locations in South Australia’s start-up hub, Lot 14, a manufacturing facility in Sydney, and a small team in India. Before he’d made that fateful call, he was watching StarTrek: The Next Generation.

That’s the micro-environment, but the macro environment was exciting, too. Australia had just established its Australian Space Agency in 2018 (we were the last country in the OECD to develop a sovereign space agency), plonking it in South Australia.

“That enthusiasm and leadership that was around space, that belief that space was going to happen in Australia… Without that sort-of background environment, it would have been really hard to believe people like us could get going in that,” Freney says.

But Kulshrestha had his eye on the trends: SpaceX had established a good cadence of launches, the cost of launch was dropping, and more satellites were entering orbit.

“We’d solved the first mile, which was to get to space,” Kulshrestha says. “But the thinking was, the second mile was also important. How do you sustainably and safely support a large population of satellites in orbit?”

The world’s first satellite launched in 1957, and in an open letter in the March 2023 issue of Science, researchers estimated there were 9,000 active satellites in orbit. That number was expected to grow to 60,000 by 2030. And as a result of increased space traffic, there were touted to be 100 trillion objects – including bits of debris and defunct satellites – floating around in space. That’s called space junk – and scientists are becoming increasingly worried that the exploitation of earth’s orbit could result in increased collisions and catastrophic damage to satellites. No satellites means impact to communications (think: internet data, telephone calls, TV broadcasts), to navigation systems (GPS and sat-navs, ship tracking and aeroplane tracking), and to imaging and monitoring systems (which impact climate change and monitor natural disasters).

We’d love to see the sovereign capability built here, and Australia benefitting from that economic complexity, jobs growth and taking an outsized share of the market opportunity.”

– George Freney, co-founder, Space Machines Co

“There will be an exponential increase of space debris in the next 10 years,” Kulshrestha says. “If there is a service available in orbit, the amount of space debris can be controlled and managed.”

You can think of Space Machines Company’s service as being similar to the NRMA roadside assistance – though, rather than individuals, it’ll be space corporations signing up to their orbit-side assistance subscription. (In fact, Freney actually sat on the board of the RAA (South Australia’s roadside assistance company) for more than a year).

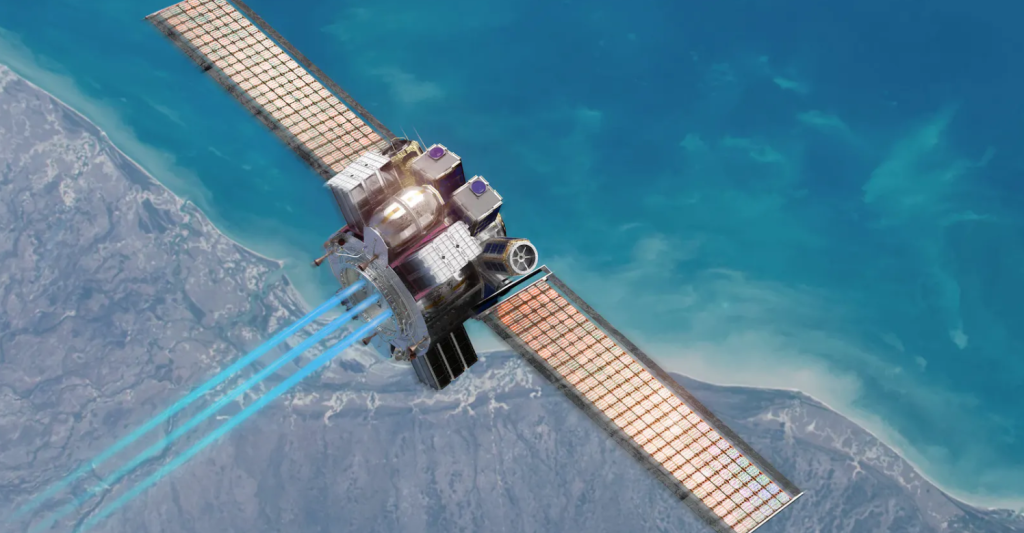

The orbital servicing vehicle they’ve been working on for the past two-and-a-half-years, Optimus, will launch with SpaceX’s Falcon 9 mission in March next year. It is a 300kg satellite that carries a powerful engine and a bunch of sensors that allow it to maneuver in orbit.

Once Optimus gets into orbit, it will put itself in park-mode, and await its next mission. If a satellite breaks down, the operators will call Space Machines, who will then plot Optimus’ path to the satellite, inspect it and work out what’s wrong.

“We can then provide situational awareness back to the customers, and as the technology roadmap develops, we can start to provide diagnostics followed by repair, debris removal and life extension,” Kulshrestha says.

Building a service satellite and shooting it into space is capital intensive, the pair admit, and so far, they’ve raised an undisclosed amount from private high-net-worth investors in Australia and overseas, and leveraged the R&D tax incentive to get Optimus to this point. They are in the process of raising capital to fund their next milestones, which include three more vehicle launches and proving the roadside-assistance model.

“It is going to change the economics and sustainability or resilience of space infrastructure,” Freney says. “That has everything to do with protecting the planet and our freedom.”

And it’s also important for Australia’s sovereign capability – or the nation’s ownership of, and manufacturing capabilities for, things relating to space.

Failure is something you need to be comfortable with.”

– Rajat Kulshrestha, co-founder and CEO, Space Machines Company

“We’d love to see the sovereign capability built here, and Australia benefitting from that economic complexity, jobs growth and taking an outsized share of the market opportunity,” Freney says.

The team have opened a research and development office in Bangalore, India, close to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), with 10 staff, and partnered with Indian defence manufacturer Ananth Technologies to collaborate across missions, integration and testing, tech developments and supply chain. It comes as India announced it plans to send an astronaut to the moon by 2040 and send its own space station into orbit by 2035.

“We leveraged the long space heritage that India has had,” Kulshrestha says. “That space heritage and the learnings India’s had has taught us how to do this in a way that’s sustainable but also cost effective.”

And while SpaceX’s recent Starship test flight didn’t go to plan (read: resulted in an explosion), the team are confident about its Falcon launch, as it’s already had more than 60 flights this year. But then again, it’s space-tech, and things can go wrong.

“Failure is something you need to be comfortable with,” Kulshrestha says. “For us, what’s been really critical is that we built a team that can build spacecraft in Australia, and while we can’t guarantee what will happen, we do have a team that can do it again. That brings us a lot of comfort.”

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.