Secure Code Warrior: doing battle from Reykjavik to Bruges and Sydney.

Before he founded Secure Code Warrior, Pieter Danhieux had spent his adult life – and most of his teens – breaking into ATMs, cars, websites and banking systems. In the end, the Belgian hacker had a team of 20 to 30 white-hatted accomplices travelling the globe to find the cracks in any computer.

In 2015, now resident in Australia and employed by BAE Systems to find fissures in the fortress walls of the arms, security and aerospace company [formerly British Aerospace Engineering], he paused to look back at his career.

After 20-plus years of breaking and entering computers, it wasn’t getting any harder. The code had all the same glitches it had in the 90s.

“I realised that I was training security people in how to break in, but nobody was training the builders on how to defend,” he recalls.

“The security people are not the ones building the next mobile app, or the next website or the next API (Application Programming Interface).”

So there was the problem: How to use his hacking skills to teach software developers to avoid writing in the mistakes that security people had known about for 20 years?

He approached a few of his best team members at BAE and attempted to poach them to join him in pursuing this problem. “They were in really high-paying jobs,” says Danhieux. “And I needed to convince them to jump on this crazy idea and take a salary cut of at least 30% to 40%. I said: ‘My promise to you guys is that in a few years, you’ll be able to buy a house in Sydney and pay cash. For that, I’ll give you equity’.”

After a career in practice management at cyber security firms, Fatemah Beydoun remembers agreeing with Danhieux that there would be demand for it. But also, Danhieux had convinced her colleagues Jaap Karan Singh, Colin Wong and Nathan Desmet to sign on. “[They] were some of the smartest guys I knew, so it made that decision a lot easier.”

Secure Code Warrior was born and began building a security education platform for coders. By 2016, they’d enlisted CBA, Westpac, ANZ, and Dutch bank ING. An ING employee told Danhieux about a Belgian company, Sensei, with a rival system.

Danhieux looked into Sensei and, in an extraordinary coincidence, saw that it had been founded by Matias Madou – a good friend of his from university back in Belgium.

Where Danhieux had been business-focused, working as a consultant to corporations while still studying, Madou was more academic, guided by his school-teacher parents to strive for the highest degree possible. His PhD was in analysing code, line-by-line, to find security flaws. After university, he worked for a US company called Fortify, which did just that.

Madou was at Fortify for seven years before he had the same realisation as Danhieux – that the best way to fix insecure code was to stop it being created in the first place.

His start-up was based on a program that acted like the squiggly red line of a spellchecker, alerting code writers to security problems as they wrote them. Sensei was three people, and Secure Code Warrior was seven when the two bootstrappers met up at the 2017 RSA Conference in San Francisco.

“We were both staying in really crappy hostels in the Tenderloin – the cheapest, most unsafe part of San Francisco,” recalls Madou. “I had a shared shower. But we met in one of the nicer hotel bars. We both wanted to pretend that we were a little bit bigger than we were.”

Madou was determined that he would tell his old friend nothing about Sensei. They were now competitors. They would talk for 15 minutes, he told himself, then he’d make his excuses and split. Both fans of sweet cocktails, they hit the mai tais and it wasn’t long before the guard slipped. “And he was like, ‘Oh my god, you’re doing that! That’s crazy.’ And I was like, ‘Oh my god, I can’t believe you’re doing that!’” recalls Matou. “We were both constantly amazed by what the other was doing.” The tiki cocktails flowed over three or four hours and by the end of the night, with a bill neither could afford, the companies were as good as merged.

The marriage was formalized in June 2017 with a straight stock swap for two companies that weren’t worth a lot. Madou stayed in Belgium. Danhieux in Sydney. They kept the Australian company name and the Sensei brand name for the “spellcheck” function.

“We hustled. We were living on our own cash with a meagre salary,” recalls Danhieux. “Our office was a coffee shop in the city until 2018. In those three years, we built a product, and proved it by generating $3 million in revenue.” They went to investors in 2018, raising US$3.5 million, and used the money to hire people in Boston and London and to get an office for themselves – a meeting room in Sydney that Agence France Presse had spare. It was meant for six people, but they were soon 15, and co-founder Beydoun was expecting a baby.

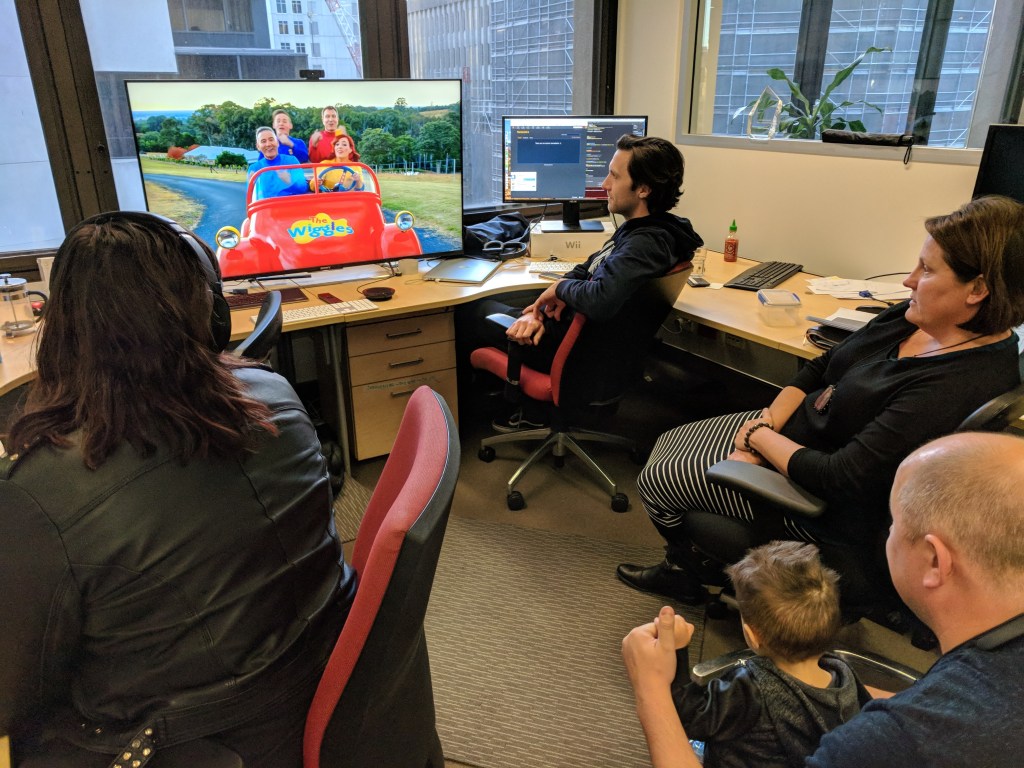

They had a sweep on the date of delivery, and whoever got it most wrong would have to change the nappies for a year. “That didn’t end up happening,” says Beydoun. She brought baby Noah to work from about two months. As he grew, toys and the Wiggles became office features. “It was great for company culture,” says Danhieux.

“The first policy we ever had was the ‘Bringing Your Child to Work Policy’,” says Beydoun. It was all very straightforward, focusing on food prep and nappies.

The following year, 2019, with revenue at about US$13 million, they raised $US47.6 million in a Series B with Goldman Sachs and Cisco leading.

Danhieux took US$16 million off the table. “I gave it to my co-founders so they could pay off their mortgages,” he says. “That was my promise: that they would be able to buy houses in Sydney. And they did.”

Copycats

The company had grown to about 100 employees when a customer alerted them to another rival – Adversary. “They were using hacking simulators to teach developers how to break into systems,” says Danhieux. “It was interesting technology with smart people.” Adversary was in Iceland.

Madou and Danhieux flew to Reykjavik in early 2020. “We met them once, bought the company, then went into lockdown for COVID-19 and didn’t see them physically again for two years,” says Danhieux.

From the beginning, Secure Code Warrior has had a remote culture, so COVID wasn’t a huge shock. But Madou, chief technology officer, admits that running a company now with 230 employees – including engineers in Iceland, Belgium, Portland and Sydney – is not easy. “I can be awake 24/7, and there’s always going to be somebody awake that needs something or wants to meet.”

Danhieux attributes part of Secure Code Warrior’s success to its Belgian/Australian culture of quiet humility, under-promising, and being under the radar. “One of the benefits of starting up in Australia is that you have a good ‘copycat market’. It is like a small version of the US.” All the kinks could be worked out with large corporate customers like Telstra and CBA. “And by the time we went to the US, we already had a mature product working. If you do that in San Francisco, from the moment you’re even testing, a competitor will pop up and try to copy you. We didn’t have anyone copy us until 2018 or 19. We had a big head start.”

Secure Code Warrior was valued at US$400 million in July when it raised another US$50 million in a Series C led by Washington-based Paladin Capital Group and including Goldman Sachs and Tidal Ventures, a fund run by former Atlassian staff.

Danhieux says the founders still hold more than 40%.

The new money raised will fund further expansion into Asia and building new features. The product is said to be used by more than 400,000 developers and 600 businesses, including JPMorgan Chase, Atlassian, Salesforce and Cisco. Secure Code Warrior hopes to be in profit by 2025.

Fundraising Facts

- 2018 Series A: US$3.5m

- Revenue: US$3m

- 2019 Series B: US$48m

- Revenue: US$13m

- 2023 Series C: US$50m

- Revenue: US$30m

- Total Funding: US$101.5m

- Valuation: US$400m