Australians have spent the past few years “going from one disaster to the next”, leading to extreme fatigue, adrenal fatigue, and, in many cases, burnout. Under new Federal Government laws, employers are legally responsible for supporting employee psycho-social well-being. But with poor mental health costing the Australian economy between $12.2 billion and $22.5 billion, there is much more work to be done.

Beyond Blue CEO Georgie Harman knew only too well that things weren’t right within herself when she began drinking heavily and feeling isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic. She was living and working alone while leading a national mental health response to the global pandemic, one of the busiest times of her career. It was, in her words, “a lot”.

Harman says that she was fortunate enough to recognise the slip in her mental health because she had been in a similar situation before. In 2014, while leading Beyond Blue, she experienced her first depressive episode, triggered by changes in her personal life. In that instance, she began drinking heavily, isolating herself and “feeling low”. It took a friend telling her that she “wasn’t acting like herself” to realise that she could no longer fool people into thinking she was okay.

“It was a bit of a case of the boiling frog for me. A friend and colleague told me, ‘ I don’t think you’re in a good place, ‘ which made me realise that the mask I had been wearing wasn’t working.”

Harman says while “it sounds trite”, focusing on three things: sleep, diet and exercise, along with psychological therapy and medication, helped her to recover.

Harman says that early intervention is crucial to good outcomes when treating burnout. Research by Beyond Blue shows that since the pandemic a growing number of people are delaying getting help. She says around 50% of the people who present with “acute” mental health issues at Beyond Blue delayed seeking assistance, because they believed symptoms were not “serious enough” or they didn’t want to take away services from people who “need it more”.

“There’s the sense that we have lurched from crisis to crisis in the community over the last few years starting with the bushfires, and then obviously [the] pandemic and there are some extreme weather events [that] have happened since then.

“Now, this economic and household stress is incredibly real to people. All of that has had a compounding effect,” Harman says.

Supporting employees’ psycho-social well-being and mental health is now a legal requirement for Australian companies. In October 2022, the Work Health & Safety Regulations (2017) was amended to give employers a duty to identify and mitigate work-

related psycho-social hazards, including harm to mental health.

Burnout, by definition, can result from too much stress at work or stress that goes on for too long. It is a “combination of feeling exhausted, feeling negative about (or less connected to) the work or activity you’re doing and a feeling of reduced performance”, according to Beyond Blue.

Harman says it is important to understand the distinction between burnout and stress. While stress can be managed in the short term, burnout usually occurs after prolonged stress and challenge, leading to physical and mental exhaustion. Burnout, unlike anxiety or depression, is not a diagnosed condition – however, a significant proportion of people who experience burnout experience symptoms of both.

The State of the Global Workplace 2023 Report by Gallup found that Australian workers experienced some of the highest stress rates in the world. The report found that 47% of employees experienced daily stress, with women reporting slightly higher stress levels than men. An alarming 67% identified they were “quietly quitting” – or “not engaged” with their work despite being physically present, the research showed. Similarly, research by healthcare technology company TELUS Health found in its Mental Health Index that more than one in three Australian workers currently have a “high mental health risk”.

Aside from being a legal requirement, providing a “mentally healthy workplace” also benefits the bottom line, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers. Research by the firm Creating a Mentally Healthy Workplace (commissioned by the Federal Government) found that organisations can expect a positive return on investment (ROI) of at least 2.3 when they successfully create a mentally healthy workplace. In other words, for every $1 spent, there is a $2.30 gain. It estimates that mental health conditions cost Australian workplaces more than $10.9 billion annually.

Beyond Blue’s Harman says it couldn’t be a more critical time for companies to meet their obligations. She describes the pandemic as a “seminal experience” for Australians that changed people’s view of work and what it means to them. When organisations expect workplaces to return to “business as usual”, it can leave employees feeling overwhelmed and “struggling to come up for air”, she says.

“[What] we have seen from our services and insights, and listening is still an incredible sense of fatigue. While we are productive, what hasn’t shifted is the sense of almost visceral exhaustion that many people are still experiencing.

“People are struggling, and it’s playing out in terms of their ability to cope, their resilience, their connection with work and family,” Harman says.

Back from the brink

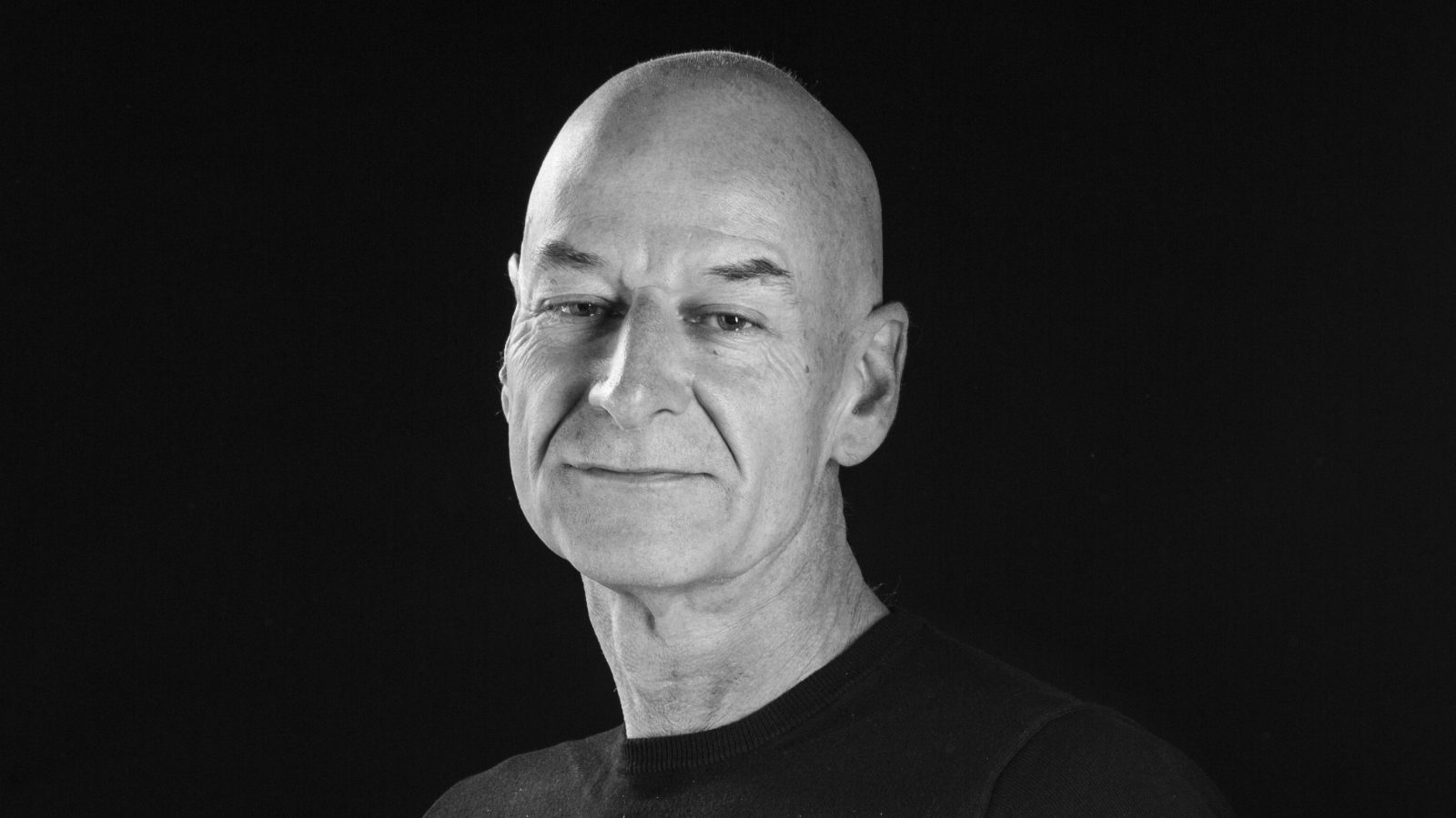

Matt Berriman, co-founder of RealVC and chair of Mental Health Australia, says recognising symptoms of burnout early and taking action plays a crucial role in good outcomes.

Berriman, who has bipolar disorder, has suffered from episodes of poor mental health, especially after his $200 million tech business, Unlockd, collapsed in 2018, shortly before its IPO, after Google controversially banned its App. Berriman – bankrupted by the collapse – is still pursuing Google in US courts for anti-trust behaviour.

“I founded a business called Unlockd, and we grew that to around 90 staff members in seven countries and raised about $70 million in capital,” he says. “We’re now five years later down the road of a court case against Google in California for anti-trust behaviour.”

“Business is a marathon, it’s not a sprint. If you’re doing that kind of thing for five, 10 years, then you will burn yourself out.”

He says for people feeling low, helpless and exhausted, having people they can confide in personally and at work can mean the difference between life and death. In Berriman’s case, his rock bottom culminated in a failed suicide attempt after trialling numerous therapies and drugs to no avail.

“I think I had tried 16 different medication types, had ECT therapy and TMS, and wasn’t getting any better. I was like: ‘If this is what my life is, I’ve got no interest in it. I don’t want to live it’,” the 39-year-old says.

Berriman survived his suicide attempt and received sound advice from a stern Scottish doctor that he will never forget. “I woke up, and one of the doctors in the ED said to me:

‘You seem to be good at business and sport, but you’re pretty shit at trying to kill yourself, so don’t do that again’,” Berriman says.

A small group of about six people, including his sister, best friends and his psychologist, helped him recover. He, like Harman, believes that focusing on sleep, diet and exercise, in addition to medication and psychological support, also aided in his recovery.

“I still had some pretty low days after that, and I still do if I’m honest – it is part of the condition [bipolar disorder] – but now I have a better understanding of when I’m beginning to feel low and how to manage it.”

Two years ago, he was approached by a headhunter to lead Mental Health Australia – the national peak advocacy body for the mental health sector – as chair.

“We’ve got a dual role to raise awareness around mental health, and to help change the system so people can get treated,” he says.

Learn how to switch off

Berriman says burnout in the workplace and associated poor mental health has been fast-tracked by the pandemic and the overuse of technology. Employees today are “expected to be ‘on’ 24/7”, he says. “It used to be in the old days you finish at a set time, and once you get home, you can’t get access to anything [until] the following morning.”

“It [burnout] can be a slow burn where you’re just running on the treadmill so hard across different areas of your life, and then all of a sudden, your adrenal glands aren’t producing enough adrenaline to keep being in that fight or flight mode, and then you just crash.”

Berriman – who co-founded RealVC with businessmen Martin Dalgleish and Paul Saunders – says he continually checks in with the founders of the businesses he has invested in to see they prioritise their well-being and mental health. He says leading by example is important in promoting a safe work culture.

“If I see them [the founders] emailing me at 3am, I’m the first to call them out by saying, ‘What are you doing? Why couldn’t that wait until 8am?” he says. “Because business is a marathon, it’s not a sprint. If you’re doing that kind of thing for five, 10 years, then you will burn yourself out.”

While there are numerous well-being Apps, employee assistance programs and services used by organisations to support mental health, it is vital that companies have more than a “tick the box” approach to well-being, Beyond Blue’s Harman says.

Employees will see through a “tick the box” approach.

“If you treat this as a textbook exercise…employees will see straight through it. Good practice starts at the top – leaders need to be seen as practising this stuff every day. It is one of the top three things people look for when looking for jobs.”

Harman says with the lines more blurred than ever before between work and home life, workplaces have an increasingly important role in checking in on their employee’s well-being and mental health.

Companies need to promote a “safety culture” and ensure managers are adequately trained in dealing with matters of employee well-being. “Workplaces need to equip leaders to understand and support employees properly. Good training gives them the confidence to know how to act. We know that good outcomes come from early action.”

“Managers need to ask themselves: ‘How would I like this conversation to go if I was struggling?’”

“I think the contemporary leadership model is about co-designing what good looks like with your teams, not just snapping back to: ‘I’ve got the corner office. I expect everybody to be here five days a week.’”

Rose Zaffino, psychologist and TELUS Health director of clinical services for Asia Pacific has more than two decades of experience working with organisations and individuals on mental health and well-being at work. Zaffino – who works directly with employees who have sought counselling help through employee assistance programs – says isolation and loneliness are common issues for employees, especially those who work from home.

“The thing with burnout is it isn’t a solid medical diagnosis, but it can lead to depression. Potentially, depending on what sort of area people work in, such as frontline workers, it can contribute to post-traumatic stress.

Zaffino says that a lack of control in the workplace adds to a feeling of helplessness, which can contribute to burnout. “Unclear job expectations are a big factor, especially around organisational change. People ask: ‘What exactly is my job, what are the tasks I need to complete, and what are my KPIs and how will I be assessed?’”

Zaffino says that having conversations with employees about how to support them in their work best while having a solid management plan for employee well-being and mental health is the best way to build a psychologically safe workplace.

“Having an environment where it’s culturally safe, to be able to raise concerns and to know they’re going to be dealt with is extremely important. It’s a holistic approach, not just for mental health but physical exercise and financial safety – it’s all of those things. It’s also about good communication.”

More advice and research on building psychologically safe workplaces and mental health can be found at Beyond Blue’s website www.beyondblue.org.au, Mental Health Australia www.mhaustralia.org and The Black Dog Institute www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

Mental health at work

Almost 1 in 5 people experience poor mental health each year.

Almost 50% of people will experience poor mental health during their lives.

Many people spend a third of their lives at work.

Poor mental health costs the Australian economy $12.2 to 22.5 billion annually. (According to the Australian Government Productivity Commission).

If you or anyone needs help:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

MensLine Australia: 1300 789 978

Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467

Beyond Blue: 1300 22 46 36

QLife: 1800 184 527