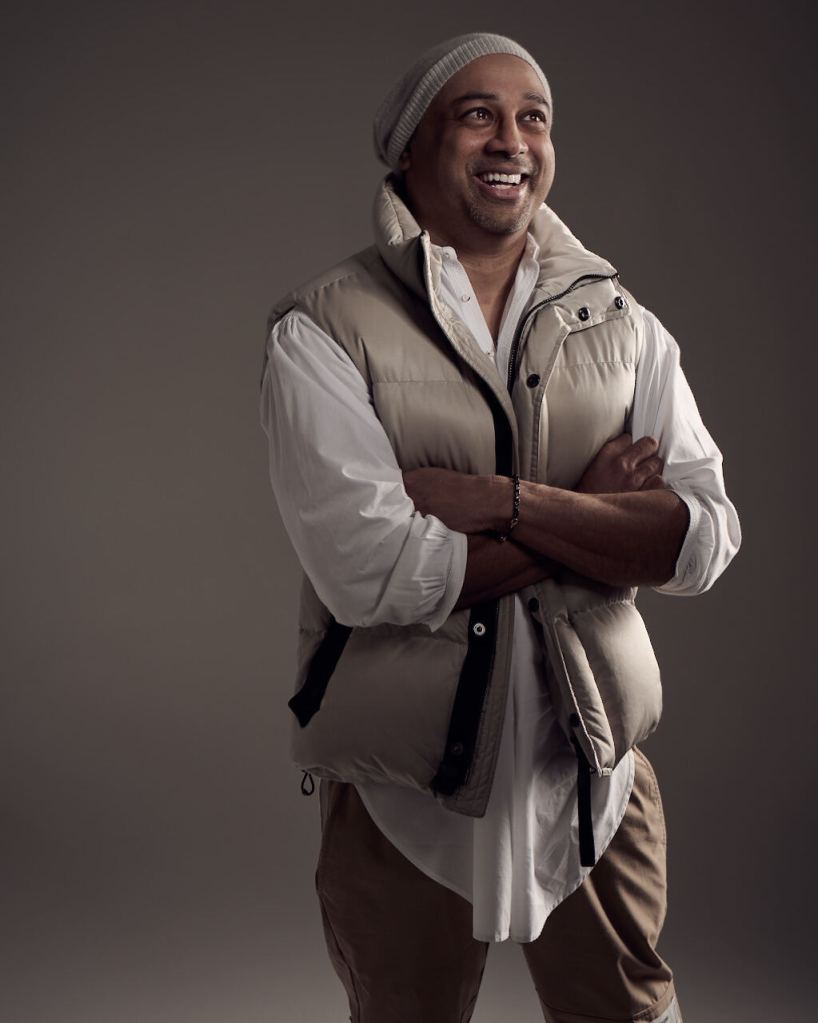

The Zambrero Mexican restaurant chain accounts for just half of Sam Prince’s $1.57-billion fortune. And after an existential shock in 2016, he’s pivoted his priorities back to business, with plans to make much more from what he says will be entrepreneurship’s next big thing.

Forbes Australia Issue 7 is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

Sam Prince might be best known as the doctor who founded a restaurant chain and gave away a lot of free meals, but what really floats his boat is entrepreneurship.

“It’s what I’m thinking about when other people are walking the dog,” he says.

While all those pooches have been out on walkies, Prince has been flexing a desire to intellectualise enterprise. And to leverage his insights into what he predicts will make him a lot of money and be the next big thing at the cutting edge of business. You’ve heard of VC, incubators and accelerators. Get ready for “EG”, Prince’s “Entrepreneur Generator”.

He’s been reassessing his priorities since 2016 when he was told he most likely had terminal cancer. It was a turning point.

Prince had maintained 100% ownership of the Mexican fast-food chain Zambrero until last year when he took $250 million in a funding round led by Metric Capital and included his friend Scott Farquhar’s Skip Capital, at a valuation of “about a billion” dollars, leaving Prince with 72% of the business.

But Sam Prince is, possibly, worth more than twice that. His interests spread a lot further than Zambrero’s. In a valuation provided by Prince and seen by Forbes Australia, he is worth $1,569,400,000, with a licence-model medical company, an employment app, a beverage business and a chain of flash restaurants. Now, he plans to grow that pie at an ever-increasing rate with the launch of his entrepreneur generator.

While the classic pattern of the self-made uber-rich is singularly focused on making a pile before giving a chunk of it away, Prince started giving it away before he had very much. But as he approaches his 40th birthday in November, Prince is stepping back from his charities – just a little – and going the full enchilada on exponential growth.

The insight

Sam Prince’s parents came from Sri Lankan villages. Bright kids, they met while on scholarships at university in Glasgow. Their son is acutely aware that his origin story requires a long list of kindnesses for him to exist: that a minister had to champion free education, even in the remotest of villages; that a woman had to persuade his grandfather to move his mother to a better school; that the Colombo Plan would send a village girl to Scotland for a PhD in economics.

They moved to Canberra when Prince was three. His parents had good jobs but lived simply in a one-bedroom apartment in a drab 70s block, “The Beetaloo Flats”, on Canberra’s north side. Being educated, the onus had fallen on them to take care of the extended family. “They had to buy stuff and put their brothers’ and sisters’ kids through school,” says Prince. “I didn’t understand this till I got older.” He was made to appreciate Australia’s free education and healthcare. “We were always conscious we were lucky.”

Prince’s mother had wanted to be a doctor, and he hypothesises that’s why he decided on that path at an early age. “To this day, she says, ‘You still have to be a doctor. You don’t want to do business all the time.’ ‘Why, Mum?’ ‘Because if you do business all the time, you’ll turn into a dickhead.’ She’s got a point – as a doctor, you think about other people’s problems which makes you less of a dickhead.”

Getting into medical school felt like climbing Everest to Prince, especially from his sports-orientated Lake Ginninderra College. He thinks of it as one of his greatest achievements. Even so, he sensed a future outside of doctoring, and he started reading up on the great entrepreneurs of history. “I remember thinking when I was at med school, about 18, that if everything else fails me, at least I’ll be a doctor. I still love the art of medicine – the patient piece – where you’ll do everything possible to get in between the patient and illness. I knew medicine would be a big part of my life, but not my entire life.”

Working café jobs and studying, he found time to become a Lifeline counsellor at 18. He’ll never forget his first call: “I’m cutting myself right now.” Surrounded by supervisors, he stuck to the script. And the caller hung up on him. He thought he’d screwed up. He needed counselling. “I learnt that if you’ve got a patient in your room as a doctor, you can fumble your words or say the wrong thing, but they’re still in your room. At Lifeline, if you lose empathy for a second, that’s it. They’re off the call. It underlined the concept of empathy in your voice. That’s the only thing you have.”

He got better at the tone. He learnt to lead with it.

Living in a “beer-soaked” college at Monash University, he got a job working on the floor and in the kitchen at a nearby Mexican restaurant, Nachos Cantina. He also worked at other Mexican eateries, and somewhere in there, he realised that Mexican food was about to evolve into something fresher and modern – and that he could drive that evolution. He would open his own restaurant.

First, he experimented – obsessing about how beans interfaced with tortillas and meat, the order that they hit the taste buds, the length of time the meat needed to be cooked to absorb flavour, how to cut the romaine lettuce, how the squeezed lime fitted, how the guacamole oxidised.

After his 2005 end-of-year exams, with $16,000 in savings and hocked possessions, he was ready to move. “I was very efficient, so I figured there was just enough time – to go there (Canberra), sign a lease, build a restaurant. Get my mates to help me with everything required to convert an old takeaway into a Zambrero. Katrina, my girlfriend, was a graphic designer. She was fantastic and accommodating and was a great supporter of Zambrero. Too often, she’s forgotten.”

He was still working on the individual ingredients. “When I rolled it all together for the first time into a burrito, probably a week from opening, I had a tear in my eye. I had a very strong gut feeling – ‘This is not just one restaurant.’ It was so clear.”

On opening day, he had a sign in the window, “Zambrero, franchising across Australia”.

He employed a manager and a few weeks later was back in Melbourne at Monash. At the end of that year, he returned to Canberra Hospital for his internship, working the night shift to free up the days for Zambrero. He’d learnt to function on little sleep during high school and now took it to the next level.

He’d be rolling burritos with his hospital tie tucked into his shirt pocket, doing the accounts out the back, figuring out the branding, the processes, the website, how to scale, and an ops manual. “It was kind of funny, but I honestly felt it was like a piano that I could just play,” he says.

Two years later, he sold his first franchise. If you ask him what his major insight was, he nominates timing. “The gap was Mexican food in 2005. The window had opened and would only be open for two years.” Competitor Guzman y Gomez was founded in 2006.

Paying it back

By then, he’d already gone to Sri Lanka with a team wanting to help during that country’s brutal civil war. “I was getting mixed up with Doctors Without Borders, MSF. Those guys were like these superstars, the Jordans of aid work. I was probably insufferable back then, with a bleeding heart, and kind of lost.” He recognises a condescension in his attitude. “My people needed saving, notwithstanding my people never asked to be saved. I quickly realised, ‘If you don’t have a clear plan of what you’re doing, you can just get in the way.’ Some of these guys in MSF schooled me: ‘Why are you here? Honestly! Why are you here? This is a dangerous place.’ And I led a whole bunch of volunteers but realised I was lost. ‘This is actually not that much to do with me.’”

He went back to pondering the many kindnesses his family had received.

“All we’ve got to do is take the ego out of this and try to recognise what kindness we’ve received and try to uphold that, and maybe if we’re skilled, we can amplify it.”

Sam Prince

He started building IT centres in village schools that barely had walls. “I just leapt into action. I realised there was this digital divide. If you hadn’t seen a computer, the chances of going to uni were slim, and your chance of keeping up at university was almost zero. I’m in my early 20s. Zambrero is paying for it all.

“Then I realised, ‘You know what, I think our customers would love to know what we’re doing, and we could do more.’ I started the Plate 4 Plate program. For every meal we served, we’d donate a meal to people in need.” Large signs appeared in the restaurants to shout about it.

By 2010, Zambrero was approaching a dozen franchises. Prince was still a part-time doctor at Canberra Hospital when he felt he should bring the charity home to Australia. He wanted to end a disease. He didn’t know which disease yet, but in forming a board for his charity, he was able to convince Nobel laureate astronomer Brian Schmidt, Aspen Medical founder Glenn Keys, ophthalmologist Hugh Taylor – who’d learnt at the feet of Fred Hollows – and his medical mentor, Frank Bowden, who’d already played a role in ending the sexually transmitted disease Donovanosis in the north, to come on board.

They talked to Indigenous communities in the far north who identified scabies as a huge problem. Seven out of ten children in remote communities got the mite before they turned one, which could cause secondary infections and long-term heart and kidney problems.

They were told one in 15,000 cases became “crusted scabies” – a severe form in which millions of mites infect a person and create a scaly effect, turning carriers into super spreaders with immune systems so overrun that 50% died from associated infection. The team realised that to reduce simple scabies, they needed to find and eliminate crusted scabies. They found that the true rate of crusted scabies in Arnhem Land was not one in 15,000 cases but one in 400.

In the early days, Prince was fascinated by R-naughts and the theory of it all but found that was the easy part. The hard part was human resources – finding the best people in the world, convincing them to move to Arnhem Land, and keeping them happy there.

One Disease created a registry and successfully lobbied the government to make crusted scabies a notifiable disease. And while One Disease declared the disease “eliminated” in 2022, “elimination” was defined as a less than 5% recurrence rate. There were, in fact, 76 cases in the Northern Territory in 2022, up from 61 the year before, a NT Department of Health spokesperson said, adding that most incidents were now recurrent cases in people with compromised immune systems.

Three steps ahead

When Karim Messih – former general manager of Video Ezy and Jetset travel – came in for a job interview, he remembered how those around him had built up Prince as superhuman. And he did have an aura, young and cool, T-shirt and jeans, but also a down-to-earth ordinariness. Prince didn’t ask typical interview questions. He wanted to know the last book Messih had read, the last movie he’d seen, and how he felt about charity.

“He was passionate about his Plate 4 Plate program,” says Messih. “It was at the core of the business, so when we later interviewed people for franchises, they had to have that synergy with the brand. It was more about the type of person. He would sit in on every staff interview, which is unheard of. But in the end, it was critical. He knew that if he had a team he could trust, even if they weren’t the best person, they were the right person to fit into the culture.”

The first week, Prince took Messih for a walk. They talked about what they wanted to be famous for – feeding the hungry and producing great food. They walked into a competitor and ordered every item on the menu, and Prince critiqued each one. “I was the old hand. I have 30-odd years in franchising. Sam was the innovator, thinking three steps ahead of anyone. I complimented him. We had 33 shops, no real systems or processes, and we built that up. I learned a lot from him.”

Prince kept introducing new menu items. He demanded gluten-free bread that didn’t break and a salsa recipe from his mum. When he explained to Messih why he’d never sell to private equity, he said, ‘We’re product people’, and pointed at his mother’s salsa.

“He wasn’t dictatorial. He always asked for an opinion, even on things he was strong about. He was a great listener. He’d always have time to listen about you and your world.”

Karim Messih on his former boss Sam Prince

Prince didn’t listen, though, when he announced that they would take on the US. Messih told him he was crazy because of Chipotle’s stranglehold.

“But the more we researched it, the more we talked, the more we realised he was right,” recalls Messih. They first went into Boston and Rhode Island, but both have since closed. There appears to be only one Zambrero restaurant open in the US, in Florence, Kentucky.

A fist-sized lump

In 2016, Prince started coughing blood. “I’m fine, I’m fine,” he’d reassured himself and those around him. After all, he was living healthy, eating well and exercising. But there was the stress. One Disease was struggling to keep boots on the ground in the Northern Territory. Zambrero was at about 80 outlets and was throwing up all the dramas of stellar growth and opening overseas. His latest obsession was his upmarket restaurants Mejico, Indu and Kid Kyoto. The Sydney-based restaurants were killing it but chewing up headspace.

He’d eventually found time for a chest X-ray, and he sensed his doctor was almost embarrassed to put the image on the lightbox. It showed a fist-sized shadow in his ribcage. “He knew I knew what it was,” says Prince. “You need to go home,” the doctor said. Prince went home. He was lucky to have eminent medical friends who swung in behind him. Lung cancer was the grim consensus. With a tumour the size of a fist, his chance of survival was low. More tests were needed.

So he found himself in the radiologist’s waiting room waiting for CT scan results with his mother, lost in his head, in problem-solving mode – the business, the charities, the people.

“My mum was incredibly sad. She was teary,” Prince recalls, pausing to hold back tears on a Teams call from Florida, where he spends much of his time. Twenty-seven seconds later, he resumes. “She was just very sad but strong. A woman in her mid-50s came out. I could tell she was flustered. She was flustered because she was busy. I know what it’s like to be busy as a doctor.”

The radiologist sat down next to them in the quiet, crowded waiting room and gave it to them straight. She thought it was cancer. “And I remember asking questions about differentials and the likelihood of surgery,” recalls Prince. “I don’t think she was anticipating sophisticated questions. She was already rushed. She didn’t want to explain her position. That would take up more time. I guess that’s why she blurted this sentence out, which I’ll never forget: ‘Either way, you’re going to need chemotherapy.’ She said it so rudely and so loudly. All the other people heard, and I realised, ‘That’s how it is’.”

Even the recorded voice in the CT scanner had been mean. “Breathe,” it barked. “Hold your breath.” There had to be a better way, he thought.

A few weeks later, he went to the hospital for a biopsy. He rang his 23-year-old commercial director Bianca Azzopardi from a hospital bed and told her he wanted her to take over as CEO when current CEO Karim Messih retired, that they could give a billion meals away by 2025. The biopsy was taken through a hole at the bottom of his throat. He’d remember the moment of glee in the doctor’s face. “I’m so glad to tell you, Sam, it’s Sarcoidosis. It’s not the other diagnosis we thought it was.”

Prince felt more emotion in the good news than in the bad. He evokes Fight Club and the stoic philosophers to express the benefits of “negative visualisation”, to imagine losing everything. He went home to heal and to think. His negative experience with the radiologist still rankled him.

“It inspired me to say, ‘Hey, I’m a doctor, an aid worker and an entrepreneur. If I can’t dream up a better way of going through this system, then who can?’”

Sam Prince

Prince didn’t return to work for “a month or two”. It gave him time to think. “I came back with energy. I knew health and technology were coming together. I knew it was a good time to reshape healthcare and add an attachment of being connected and compassionate for everybody.”

Sodoto: the entrepreneur generator

By the end of 2016, his franchised medical business aiming to mash up empathy, tech and integrative health – Next Practice – was born. It now has 16 clinics in Australia and recently raised $200 million – unannounced – for expansion. He predicts there’ll be 30 in the next year. He bought a North American electronic health records company last year, and it has been integrating its AI tech with the Next Practice clinics and the Medicare system before, he says, they’ll be expanding to the UK and Canada.

But health was just a part of his thinking. At nights and on weekends, during that dog-walking time, he was thinking about entrepreneurship. When mentor Brian Schmidt – the ANU vice chancellor who’d won the Nobel Prize for his part in discovering the accelerating expansion of the Universe – said to Prince, “I put the entire universe together merely through observation”, Prince wanted to apply that to entrepreneurship.

In 2013, he joined the Young Presidents Organisation (YPO), the worldwide club for young leaders of large companies, and couldn’t help studying those in his chapter, people like his new friends Scott Farquhar of Atlassian and Employment Hero’s Ben Thompson. “I was like the David Attenborough of the entrepreneurial world,” says Prince. “I watched and made my observations

quietly and started my own experimentation.”

Indeed, fellow Young President Jason Lavigne – the Mamamia co-founder – says Prince came across as aloof initially, but “when you spend time with him, you quickly realise it’s just about him absorbing, processing and considering each situation he finds himself in.”

Prince realised his strong views on entrepreneurship contradicted mainstream thinking: that entrepreneurs were born, not made. “I read thousands of papers to figure out what we were talking about,” he says. He wrote a 40-page academic paper with seven pages of references on his definition of entrepreneurship, which he summarises as: “having an idea, making it real, and having it adopted by other people.”

More significantly, for what would come next, he concluded that entrepreneurs are created, not born, and their skills can be taught. “But I thought, ‘How will this translate to the plumber who wants to start a plumbing business?’ I believe the best way of teaching these skills is through an apprenticeship. It’s how I learnt medicine.

“No one thinks you’re any good till you’ve seen an appendectomy, done an appendectomy, then taught someone to do it. You ‘see one, do one, teach one.’”

Sam Prince

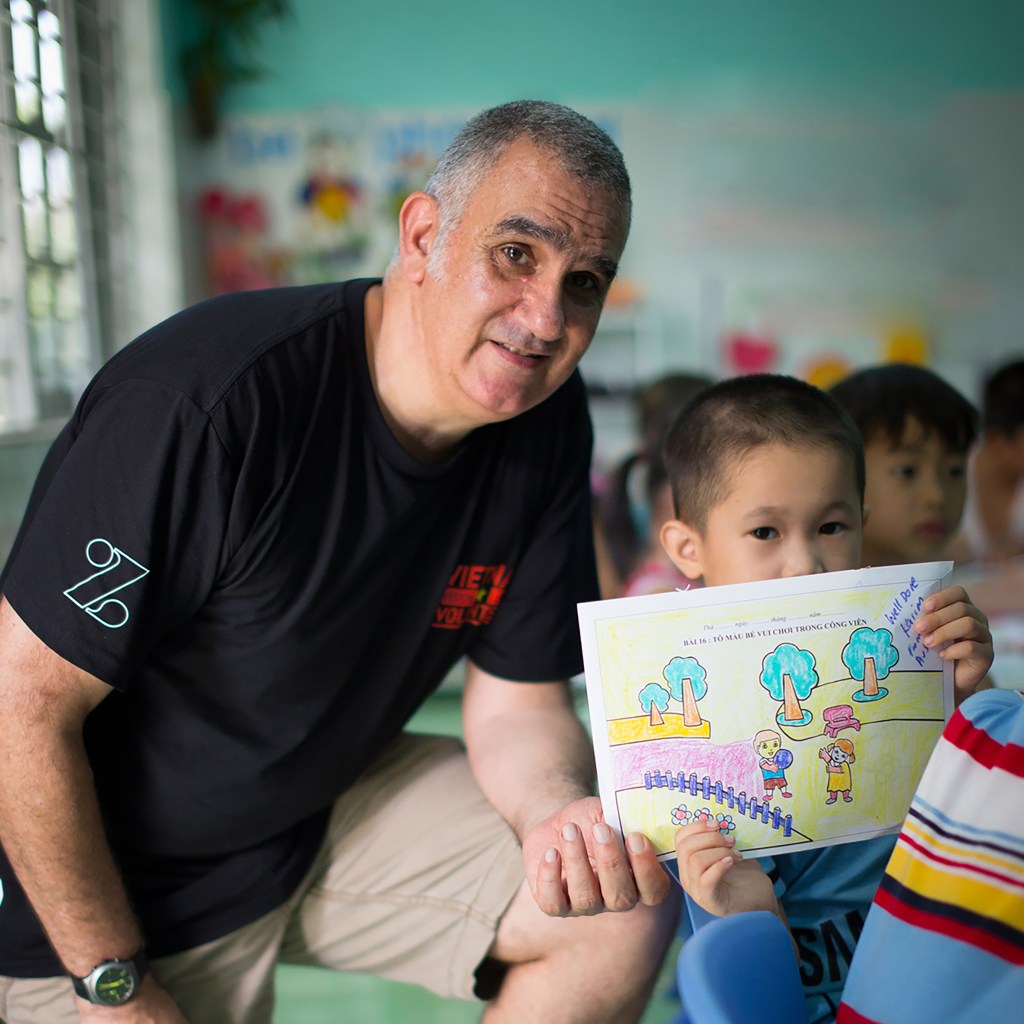

Prince had already started an experiment. He took on an apprentice, Steve Chapman, who, at 21, already had a failed start-up behind him. “Every day I would serve [Prince] as his personal assistant,” Chapman said, “doing whatever was necessary to add value such as taking notes, writing emails, organising meetings, driving Sam places, cleaning the office. Anything. Anytime. This was my way to teach myself humility; no task was too small or beneath me.”

Chapman saw Prince start One Disease and the Mejico, Indu and Kid Kyoto restaurants. “Then it was his turn to do one,” says Prince. Chapman started Shine+ Beverage, which launched a range of “nootropic” brain drinks in 2016, the year of Prince’s cancer scare, primarily funded by Prince.

Chapman took on his own apprentice, Andrew Dewaz, who, like Chapman, had come to Prince seeking guidance. “You learn a lot by osmosis, just being in the same room as Sam,” says Dewaz. Then, it was Dewaz’s turn to do one. “We’ve got this expression: it’s good to eat your own burrito or solve your own problem,” says Dewaz, “and with Sam running 200 Mexican restaurants, we know what can be improved. We saw hiring as a massive pain point.” With Dewaz at the helm, they created Zapid Hire, a hiring app for retail and hospitality that uses short personality-driven videos as both job ads and applications. Zapid Hire is funded mainly by Prince, but Dewaz has a shareholding “typical of a co-founder model”. Since launching in December 2020, it has expanded to the US with $2 million in recurring revenue and 3000 businesses using it.

Meanwhile, Prince created a curriculum for what he’s calling the SODOTO [as in “see one, do one, teach one] foundation, and in the last few months, four apprentices have come under him. They will watch him start a business before each starts a business of their own – parachuting into market gaps identified by in-house research and backed by Prince Group capital. Prince is not saying what the ventures will be. “Analytics and blueprint teams are working on global opportunities. I guess my vision is that we have bases in the US, Europe and Australia to implement these ideas worldwide.”

And when these apprentices graduate to “do one” start-up, they’ll each have two apprentices working under them – “seeing one”. And when those eight new graduates qualify, they’ll do a start-up with two apprentices watching them. And so on.

Prince has “quite a lot of blueprints” but won’t say how many. “That is the most secretive part of our group – how we come up with them, and the way we road-test blueprints is definitely special sauce.

“The SODOTO organisation is 10 years’ worth of work and thinking. We’ve ended a disease, created a food franchising business, created high-end Mexican, Sri Lankan and Japanese restaurant businesses, built a healthcare business, a beverage company and an employment technology company. So, we’re generating entrepreneurs and ideas from scratch.

Prince says the “entrepreneur generator” is already outperforming his other investments. “It’s a limited experiment. N = not many, but I feel pretty confident about this. It feels like the beginning of Zambrero or Mejico all over again.”

And where will the next round of apprentices come from?

“There’s an old adage, ‘When the apprentice is ready, the master will appear.’ I also think that when the master is ready, the apprentice will appear.”

Sam Prince

Cash converter

Prince had been “super intense” before the cancer scare, recalls his friend and fellow Young President Ben Thompson, founder of Employment Hero, via Zoom. “I don’t think he had taken a holiday for 20-odd years. He’d just work seven days a week. He’s just always on – the scare made him more considerate of balance in his life and taking a little bit more time for himself, and he’s definitely changed. He’s living in Florida, and he’s doing more adventurous stuff. He’s less of the workaholic, but I’m sure he’s still always on.”

Atlassian co-founder Scott Farquhar counts Prince as one of his best friends. In a video sent to Forbes Australia, he says Prince is one of the “smartest, most curious” people he knows. “Sam’s always into self-improvement and how to have a bigger impact on the world. One of his phrases is: ‘You are what you don’t outsource.’ Sam takes it to extremes. Sam would get a personal trainer to come every day and do an hour of training. He’ll then follow up with an hour of massage and stretches while lying face down, listening to a podcast, watching a movie, or catching up on work. He’s outsourced a chef and nutritionist to ensure he’s in peak physical performance before his assistant picks him up and drives him to work while he works in the back. That’s just his morning.”

Farquhar says music is an outlet for Prince’s creativity. When Prince says he will do a mixtape for you, he means mashups –blending multiple songs into one. “He spent the best part of a year teaching himself how to do this. He made one amazing mixtape that I listen to every week. I feel like he opens restaurants to create a soundtrack to them.” [Prince says Indu was designed around a mashup of Massive Attack’s Teardrop and the Beatles’ Across the Universe.]

Post-cancer scare, Sam Prince has also set out to allow himself more time for living. He and Farquhar went to the Grammys in Los Vegas, something he would never have done in the past. And since accepting the $250 million for a stake in Zambrero, Prince has, for the first time, allowed himself to splurge a little. “One of my burdens was making sure One Disease had enough cash. It felt like I was raising a kid. You couldn’t do anything for yourself until the kid was upright and safe.” When One Disease declared victory over crusted scabies, he could finally relax. “I thought, I’m going to take some money off the table and do some things for the people who always believed in me. And also some things for myself. That’s all I’ll say.”

He declines to elaborate on what he’s spent it on, except, when he founded Zambrero, he went to Cash Converters to sell a treasured guitar he’d paid $300 for when he was 14. He was recently in a guitar shop deciding between a Martin and a Taylor guitar. “I thought back to when I sold my Fender, and this time, I said, ‘I’ll take them both.’ Things like that mean a lot. That’s the phase of life I’m in now. It’s okay to buy the fancy pants guitar.”

Peer review

BEN THOMPSON: Employment Hero founder

“He has a thing called ‘The Path’. I’ve never seen it, but I know he’s set himself a clear set of standards. On a daily basis, he’s meditating on whether or not he’s on the path and what he should be doing to stay on the path. His mother is Buddhist, and I think that sort of comes through.”

SCOTT FARQUHAR: Atlassian co-founder

“Sam isn’t content with a normal conference room. One of his offices in Sydney is adorned with record players hanging on the wall with a guitar in the corner to be played. He’s just super into music. He even dreams of building a floating studio. It’s a bit weird because Sam doesn’t like boats.”

JASON LEVIGNE: Mamamia co-founder

“He doesn’t want to waste his own time or anyone else’s, and he likes to absorb as much information as he can before he weighs in. And when he does, it’s always a short but highly insightful and uniquely intellectual take Ð it’s never a hot take. He’s a deep thinker who reads philosophy for his downtime, and he meditates religiously twice per day.”

Sam Prince in profile

Age: 39

Born: Dundee, Scotland,1983

Migrated to Australia 1986

Studied: Monash University, medicine 2006

Headquarters: Macquarie Place, Sydney

Net Worth: $1,569,400,000

Principalities

ZAMBRERO

Founded in 2005, Canberra.

270 restaurants worldwide, including 20 in Ireland and 7 in the UK, predicting 40-50 restaurants by year’s end. One restaurant in Kentucky, US.

Prince owns 72%. He sold a $250m stake to Metric Capital and Skip Capital at a $1 billion valuation in 2022.

Zambrero claims business increased 20% post-sale, opening more than one restaurant weekly. Claims that the average restaurant payback for franchisees is 2.5 years, and the Australian network is a closed system – open only to existing franchisees

in most regions.

SAM PRINCE HOSPITALITY GROUP

Founded in 2013.

Mejico, Indu and Kid Kyoto restaurants in Sydney and Melbourne.

NEXT PRACTICE

Franchised medical clinics were founded in 2016.

Over 100,000 patients in the Next Practice network.

Raised money at $200m for expansion. Prince owns the “vast majority”.

Opened Connect bulk-billed IVF clinic in Sydney as a test case for expanding into specialist services.

16 Next Practice clinics open with plans to double that in 12 months.

SHINE+

“Nootropic” drink business co-founded with Steve Chapman in 2016.

Retail sales $30m.

20% sales growth.

ZAPID HIRE

Employment app, co-founded with Andrew Dewaz in 2020.

Active in Australia and US.

Claims 400 US organisations using it.

Over 1600+ hired applicants over the last month.

Over 600,000 active candidates in the talent base.

Valued Zapid at $21m in a raise last year – before US expansion.

PLATE 4 PLATE

Founded in 2011.

Donates a meal to the hungry for every meal purchased.

Has delivered 71 million meals.

ONE DISEASE

Claimed to have eliminated crusted scabies from Australia in 2022 and has been wound up.