Crypto casinos, chart-topping rappers, and record-breaking mansions: the newest entries into Forbes Australia’s 50 Richest, Ed Craven and Bijan Tehrani, on how they skated the edge of legality to build their combined US$5.6 billion fortune.

This story featured in Issue 15 of Forbes Australia. You can grab your copy here.

Ed Craven is still an undercover billionaire at the end of 2021, revamping the VIP-handling systems on his Stake.com cryptocurrency gambling site when he gets a call from a high roller.

“I’ve got a big customer of yours who wants to speak to you,” the VIP says. “He’s lost a bit of money. He wants better bonuses, wants to readjust his package.”

Craven wouldn’t normally take such calls, but this customer is a somebody. “No worries. Put me in touch,” he says.

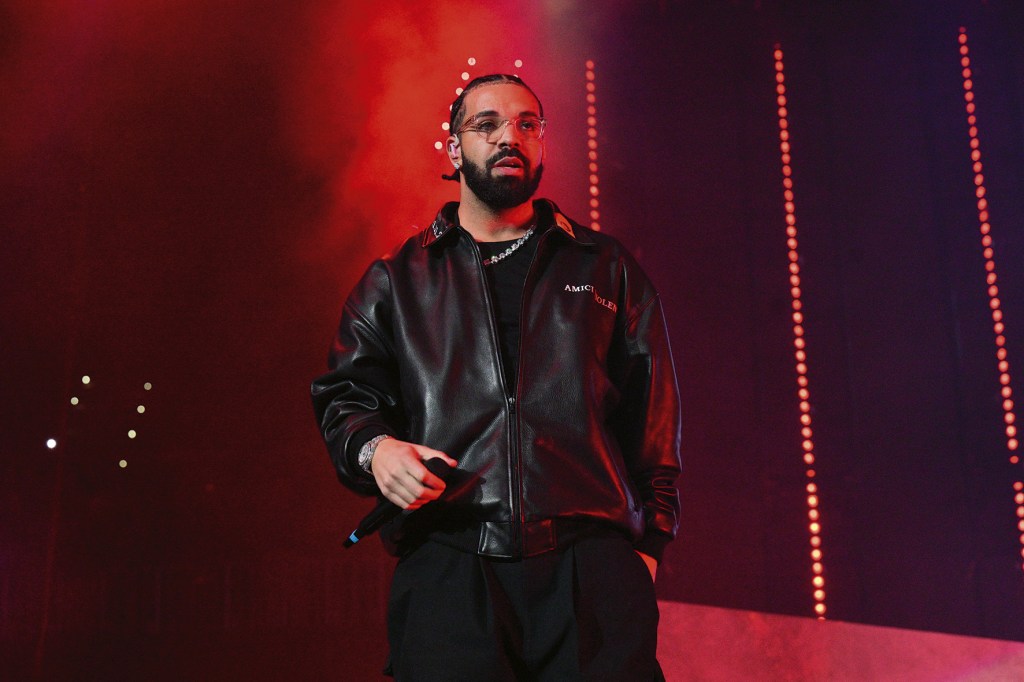

A FaceTime call from a Canadian number soon comes through. The guy on the other end looks like the Canadian rapper, Drake, who’d dominated the charts during Craven’s later high school years a decade earlier. He’s got the bling. He’s standing on a home basketball court.

It’s got to be a deep fake, Craven thinks. “I’m being scammed.”

They talk and Craven realises the rapper is real, it is Drake, and he’s loving Craven’s website. They get along, and over the next few months talk about bringing Drake on as a “brand ambassador”, whereby this unknown 26-year-old from Melbourne is going to pay a $100 million to the rapper to bet on Stake. At this point, Craven is known to the world only as “Edd Miroslav” a shadowy figure of indeterminate nationality.

The results of the Drake deal come to be called the “Drake effect”, as the rapper’s millions of social media followers see him livestream punts totalling, reportedly, more than US$1 billion on Stake.com in two months. One day, he is up US$25 million, another, he turns US$8.5 million into just US$2,000. New users flock to Stake.

In the same month as the deal with Drake, Nine newspapers reveal to the world that this multi-billion-dollar global crypto casino, Stake, is owned by two obscure Melbourne 20-somethings – Craven and his US-born, Melbourne-based business partner, Bijan Tehrani.

To give a sense of what they’ve got, the company claims that between 2% and 4% of all Bitcoin transactions involve Stake. Its gross gaming revenue [what’s left of turnover after winnings have been paid out] has gone from $105 million in 2020 to $4.7 billion in 2024.

Four months after being de-masked, Craven buys a $38.5 million Toorak mansion, then breaks a Victorian record paying $80 million for a “derelict” pile nearby. Stake pays US$12 million to shirt sponsor Everton in the UK Premier League. Craven and Tehrani launch their own livestreaming platform, Kick in late 2022, becoming the most successful entry into that market in more than a decade, and buy into the Formula One in 2023 with a US$100-million deal to rename the Alfa Romeo team “Stake F1 Team Kick Sauber”.

Their company Easygo Solutions reports a net profit to ASIC of $206 million for 2023 after paying $102 million in tax. Forbes Australia’s 50 Richest values both Ed and Bijan at US$2.8 billion. Money flows to them like iron filings to a magnet, but respectability comes harder. Craven didn’t make Forbes Australia’s 30 Under 30 last year.

“Everyone hates Ed Craven,” quipped one judge, who clarified that they didn’t really. It was just that gambling is tainted. Another points out that “social impact” is a Forbes criteria, so Craven was unpickable. [Tehrani wasn’t considered because he’s American, and was over 30.]

It’s interesting because they seem like nice young men. They pay taxes. And they’re spending hundreds of millions to buy that respectability.

Easy come Easygo

An A4 piece of paper Blu Tacked to the glass fronting Melbourne’s Collins St “easygo deliveries/inquiries please call …” is the only clue that Tehrani and Craven’s companies are headquartered here.

Craven is working at a stand-up desk out on the engineering floor when Forbes Australia is given the tour. Craven looks like actor Matt Damon – black T-shirt, big biceps and Hollywood teeth in a warm smile. He likes being among the engineers, he explains.

Each Easygo floor is decorated differently because as the company has grown [from 4 to 450 in Melbourne and another 550 globally], it has taken over the building floor by floor. And it’s got better things to do than a refurb. The only sign that the building is occupied by a money machine is the smiley staff. While Easygo had a wages bill of $29 million in 2023, it paid out $92 million in bonuses. The kitchens are stocked with free snacks from chips and chocolate to kombucha.

Sitting in a plain conference room, Craven relates how bingo on a family cruise when he was 12 sparked his journey. “It was flashing lights and quite incredible. We attended it ritually for the first five days,” Craven says. “On the fifth day there was ‘the Snowball Jackpot’ and I won about $6,000.” Craven was saved from the potentially disastrous effects of such a dopamine hit to a 12-year-old brain by the fact he was studying statistics. “I quickly figured out that the ‘house edge’ is very important. From that point on, I was fascinated by the industry.”

Around 2010, Craven, 15, in Coffs Harbour on the NSW north coast, met Tehrani, 17, in Connecticut, inside the fantasy role-playing game RuneScape. They chatted most days on TeamSpeak and, famously, got kicked off the game for setting up a casino within it.

“They couldn’t wrap their heads around this concept of betting virtual money that doesn’t exist, and how you could transfer that to real money, and what the value proposition was.”

Ed Craven

Bitcoin had launched in 2009 and was becoming known in their circle. They mined it on their PCs. It didn’t have a prescribed value and barely seemed different to the gold you could win slaying a dragon in RuneScape.

But in 2012, a basic dice gambling game, Satoshi Dice, was launched. “Everyone was using this website,” recalls Tehrani. “There was nothing else to do with your Bitcoin. It didn’t have any real value. It was hard to sell for cash.”

But they didn’t think much of the site. “We looked at how big it was and I was like, surely we can build something better than this?” recalls Tehrani.

Tehrani didn’t code, but Craven did a bit, as did some high school friends of Tehrani’s including one called Chris Freeman. They ironed out bottlenecks like making deposits and withdrawals equally easy.

Launching Primedice in February 2013, with Bitcoin at about US$20 they generated a lot of interest on the forums. “I think we took over a million dollars in bets on our first day,” recalls Craven. “I was still in high school, and I remember telling some friends. I don’t think anyone believed me. It was a business studies class at 9 am and I rocked up about 30 minutes late because I was dealing with a couple of teething issues on the website – I remember showing it to the teacher and a few people and they thought it was interesting, but they couldn’t wrap their heads around this concept of betting virtual money that doesn’t exist, and how you could transfer that to real money, and what the value proposition was.”

Craven and Tehrani vowed from the beginning to keep the house edge at a low 1%, but the bets went against them on that first night so they profited less than the $10,000 that a $1 million turnover would predict. The first-night high tapered off, but Primedice was a hit and it wasn’t long before Craven was driving to school in a second-hand Mercedes C200.

“We had some rough moments where we realised that variance is a big issue when you take larger bets,” says Craven. “You need to be very careful about bankroll management. Those are all lessons learned along the way.”

“When we got into this industry, online gambling was kind of a scam, to be honest.”

Bijan Tehrani

The site had been built by kids. It was full of glitches. “One time a guy got paid out a thousand times or something by accident,” recalls Tehrani. “One of the worst ones was, if you withdrew a negative number, say, negative ten, it would send you ten Bitcoins even though your balance was zero. Ed and I were doing all the customer support. Every time there was an issue, we’d reach out to the customer, and we would make it right. That was something that made people gravitate towards us.”

One of the biggest hitches was when a player, “Hufflepuff”, found an “exploit” in the open-sourced random number generator and won 2,400 Bitcoin [worth about $387 million today]. They tracked the stolen loot on the Blockchain over the years and saw that Hufflepuff held onto it for a long time as its value multiplied.

“Incidents like that just wiped out a lot of our earnings,” says Tehrani. “It was a tough project.”

Craven helped his parents buy a Jamaica Blue café franchise in Coffs Harbour. Tehrani fought with his Iranian refugee parents [they’d both fled the 1979 revolution and met as teenagers in the US] about whether he should stick with his economics and business degree. They won, but his grades suffered.

By 2016, the bugs had been ironed out. They had staff in Serbia! But the competition was getting sophisticated. Tehrani, newly graduated, moved to California for the summer, skydiving every day, camping in the drop zone, with a view to wingsuiting and base jumping. “Maybe I was just a bit crazy at that point,” he says.

He won’t disclose how much they’d made from Primedice, but they had “thousands” of Bitcoins as it went over $800 by the end of that summer.

He and Craven were talking about what to do next. They were still winging it. Primedice wasn’t registered in tax havens or places with lax gambling laws. It wasn’t actually registered anywhere, says Tehrani. Craven wanted Tehrani to move to Melbourne to get something happening. Tehrani wanted him to move to New York.

“The conversation was always, ‘Once we get together, we can do so much more.’ We were young guys who’d made a little bit of money and were distracted by life,” Tehrani says. But the American came to Australia in mid-2016 for a gambling conference in Sydney.

Tehrani remembers it as being a little awkward, meeting someone for the first time who

he knew so well. Tehrani had left his New York apartment thinking he was only coming for a couple of weeks. But he never went back.

“Ed showed me a really great time and he kind of accelerated things by just getting an office. Ed was quite impulsive. Boom! Now we’re based in Melbourne.” With Bitcoin now valued at around $1,000, they had plenty.

“How you look at free speech online is evolving, and I guess Elon has challenged what was previously seen as a norm.”

Ed Craven

They founded Easygo Solutions as a private company in Australia aiming to open a full-suite online crypto casino licensed in the gambling-friendly Caribbean nation of Curaçao.

Their niche was going to be low house edge and “provably-fair” technology – just more sophisticated than when Hufflepuff had hacked it. And they wanted something more immersive, with levels and rewards.

By the time they launched in June 2017, Bitcoin had gone over $3,000 –but they had little of it left. Now they had seven staff to pay. “It was a lot of pressure, and when we put Stake out, it was just a flop,” Tehrani says.

Bitcoin rocketed through $25,000 before Christmas that year and they’d missed it all. Instead, losing money on a casino no one wanted to visit. “The website had a lot of issues and people weren’t interested in what we had put out. There just wasn’t the market that we thought there was for the provably-fair games,” says Craven.

“It was just a matter of listening to our customers and making changes over time,” says Tehrani. They added games, sliced margins and took out the levels. “As we started to get more volume, we could trim those margins more. We’ve cut those margins every year since. It’s about building a long-term relationship with our clients.

“When we got into this industry, online gambling was kind of a scam, to be honest. The websites would have some deposit bonus, like deposit $1, get $20. Once you put the money in, there was no way to get it out. [They] viewed the customers as lemons. They’d squeeze the juice out, throw the lemon away and get the next one. We were trying to find ways for people to play longer.

“Stake has hit a point now where I’m confident our betting volume is the highest in the world out of any casino, land-based or online. And part of the reason for that is because our margins are so low that people are able to gamble much longer.”

Bijan Tehrani

Back in 2013 they’d tackled the trust gap with the provably-fair technology. “I was sceptical of even trusting a pokie machine down at the pub,” says Craven. Open-sourced random number generation was a selling point for the 2013 Bitcoin demographic. But now they needed to bridge the trust gap in the mass market. They figured they’d make the brand a household name.

The first big marketing deal was with the UFC in Latin America, and a simultaneous deal with then UFC middle-weight champion Israel Adesanya. It brought no immediate uptick in business. “If you look at the results day on day, you’re not going to see the value,” says Craven. “You have to zoom out. That’s been our strategy.”

Adesanya seemed fully engaged. He did his own announcement video, fronted press conferences and kept in touch. When they wanted more ambassadors, Adesanya had taught them a lesson. “We’re like, ‘Hold on, let’s take a look at who is already using our website and having them as ambassadors’.”

That’s when Craven got the call from Drake.

Right at the time, their identities were publicly exposed. Tehrani says that they’d still be in the shadows if they hadn’t been outed, but in hindsight it has helped business. “People like to know who they’re betting with. It has built trust, whereas a lot of our competitors, no one knows who operates them. And it’s unlocked other opportunities, like, doing an F1 deal when you’re anonymous would have been impossible.”

That first year of being known brought the mansions and the huge sponsorships. And the law suit. Tehrani’s old school pal and Primedice co-founder Chris Freeman sued them for $580 million claiming they’d dudded him by excluding him from Stake.

He claimed it was his idea to start a crypto casino but they told him they were going to start a fiat currency casino so he didn’t join them. They denied the claim and decline to talk about it now, beyond confirming that the action has come to an end. Freeman could not be contacted for comment.

Twitch and Kick

The livestreaming platform Twitch had been a pillar of Stake’s marketing strategy – from rapper Drake’s million-dollar bets to Craven’s own weekly chat show. But in September 2022, Twitch announced it was banning Stake due to a “lack of consumer protections”.

Stake’s banning from the platform was exhibit A in Twitch’s arbitrary wielding of power, says Tehrani. “They’d established a total monopoly. And they were doing anything they wanted. They were banning people for outrageous reasons and just created an unfair environment. We experienced that first-hand. People don’t know this, but Twitch never banned gambling. They just banned us.”

Craven and Tehrani talked about starting a rival live streamer even before they were banned, says Craven, but now they were goaded into action. At the same time, Twitch announced it was upping its take from 30% to 50% of creator revenue.

Just like they’d done with their 1% house edge in gambling, they decided their platform, Kick, would take just 5% of creator revenue. The number wasn’t arrived at after consultation with cost accountants. “It was something we just, you know, put in there and now we’re committed to it,” Tehrani says. “We made things very hard for ourselves, but the community loved it. And there became this whole grassroots movement of, ‘Come to Kick and keep what you earn and the moderation is much more fair and you can ask questions.’

“Everyone thought we were insane because a lot of people had entered this industry and failed, Microsoft had tried to launch Mixer. That couldn’t compete. They shut it down. Facebook tried launching Facebook Gaming. They’ve recently shut that down.”

Kick’s beta was up and running in under two months and it launched in three.

“Unfortunately, that led to a couple of our earlier releases having some slight flaws,” says Tehrani, “but ultimately moving fast helped us challenge Twitch at a time when they were susceptible.”

Nazar Babenko, product manager of independent analyst Streams Charts says he expected Kick to fail with its first-year strategy of luring big-name streamers, the same as Microsoft’s Mixer and Facebook Gaming had done.

“How they changed their strategy during the second year, that’s what impressed me,” says Babenko. “Kick successfully expanded into the Latin America and MENA – Middle East and Northern African – regions, attracting prominent creators like Spreen [A Spanish streamer who plays Minecraft], and some Arabic streamers.” An Arabic streamer, Maherco, has become the platform’s top performer, with 6.3 million hours of view time in December, ahead of Colombian Westcol with 4.7 million hours.

They helped to bring Kick up to 2.3 billion hours of view time in 2024, well behind Twitch’s almost 20 billion and YouTube’s 52 billion. [TikTok’s numbers are not known.] But Kick has taken fourth place ahead of a pack of smaller streaming services.

It wasn’t without controversy. One streamer was accused of coaxing underage girls to strip in video chats he initiated. He’s now banned. Others had sex while streaming.

Like other social media owners before them, the two RuneScape nerds find themselves grappling with their new power and responsibilities. “Our job is to ensure people are able to reach their audience and offer a smooth experience,” says Craven. “We have the responsibility of ensuring the right people are platformed and not the wrong people.” But in terms of having the power to influence the world, he says that lies with the creators. “We want to hand that power to them, but of course ensure that they utilise it in the right manner.”

Craven can clearly sniff the change brewing since enigmatic billionaire Elon Musk bought Twitter, and Facebook’s recent abandonment of fact checking. “People are quickly realising that the moderation policy and how you look at free speech online is evolving, and I guess Elon has challenged what was previously seen as a norm.

“Kick also has the ability to choose where it stands on that and I think we have some important decisions around our stance on where free speech ends, where hate speech begins, for example, and how to make sure that we’re in the right territory there.”

He professes no political allegiances and claims ignorance of US politics. But Kick has 900,000 unique channels, any of which could be spouting anything at any time. Kick now has 100 staff working on moderation, he says.

They also have a team working on how to make it profitable. No easy task. Twitch, for example, has never made a profit. Craven predicts Kick will turn a profit “within two to three years. But at the same time, we understand that in order to disrupt this industry, we need to rapidly grow first. That is our focus. There hasn’t been a single company that’s managed to enter the social media space in the last decade. And the fact that this small Australian company is challenging this near monopoly is really exciting.”

Tehrani has been invigorated by the challenge. Being top-dog with Stake was getting dull. “I remember when the [Kick] website came out, everyone was like, ‘this is going to fail’, ‘this is a joke’, and a lot of people continue to say that. That’s one of the reasons why we invest so heavily in this. We’re motivated by the challenge. We genuinely want to win. It really fires us up. We’ve already got to 12% of the market.” And with all this is the race to get respectable.

Last year Stake went on a hiring spree of legal and compliance staff to get into the more tightly regulated markets, opening non-crypto operations in the UK, Portugal, Italy and Colombia. In the United States, Stake operates as a “social casino” run on valueless digital coins but they still hope to enter that market, and Australia, where it remains illegal to bet on Stake.

Soon after the hiring spree, Stake informed the ASX it had bought 5% of Australian bookmaker Pointsbet. But don’t expect an imminent takeover bid, Craven says. “We do hope to launch our own betting product here in Australia, but you know right now there’s the whole world out there and we have to prioritise.” They’ve just launched in Brazil and Peru. “Having 100% global coverage is our ultimate goal.”

And their ambitions don’t stop there. Craven sees Easygo as an “entertainment and technology” company. “We love to emphasise our ability to engineer solutions. I think there’s a lot of industries out there ripe for disruption.”

Coming up Trumps

Livestreamer Adin Ross got onto Ed Craven in July last year.

“I’ve got Donald Trump coming on the livestream. Is that okay?”

“As long as you stick to our community guidelines and everything’s above board, of course it’s okay,” said Craven. But Ross’s concern was more about whether Craven’s platform, Kick, could handle the traffic.

“Don’t worry, Adin. Leave that to me,” Craven said. But he made sure the entire engineering team was in the office when Ross gave the then presidential candidate a Rolex and a Tesla Cybertruck wrapped in the now famous “Fight!” photograph of Trump. Some 500,000 people watched live as Ross and Trump danced to California Dreaming and the two-year-old Australian live-streaming platform went up another level.

What’s at stake

- Stake raked in $4.7 billion last year [after paying out winnings].

- Much of that comes from Latin America, Canada (except Ontario) and Finland, plus more than 100 countries where it is legal.

- Stake is not available in Australia or the US, but in the US, you can play a moneyless version.

- 30% of Stake bets are in crypto currency and the rest in fiat currency.

Active sponsorships

- Drake

- Stake F1 Team Kick Sauber

- Everton Football Club

- Major League Cricket

- Kick F1 Team Sim Racing

- Esporte Clube Juventude

- Enyimba Football Club

- Paarl Royals

- Champions of Champions Tour (esports)

- UFC: Sergio Agüero

- UFC: Alex Pereira

- UFC:Merab Dvalishvili

- UFC: Alexandre Pantoja

- UFC: Alexa Grasso

- UFC: Max Holloway

- UFC: Israel Adesanya