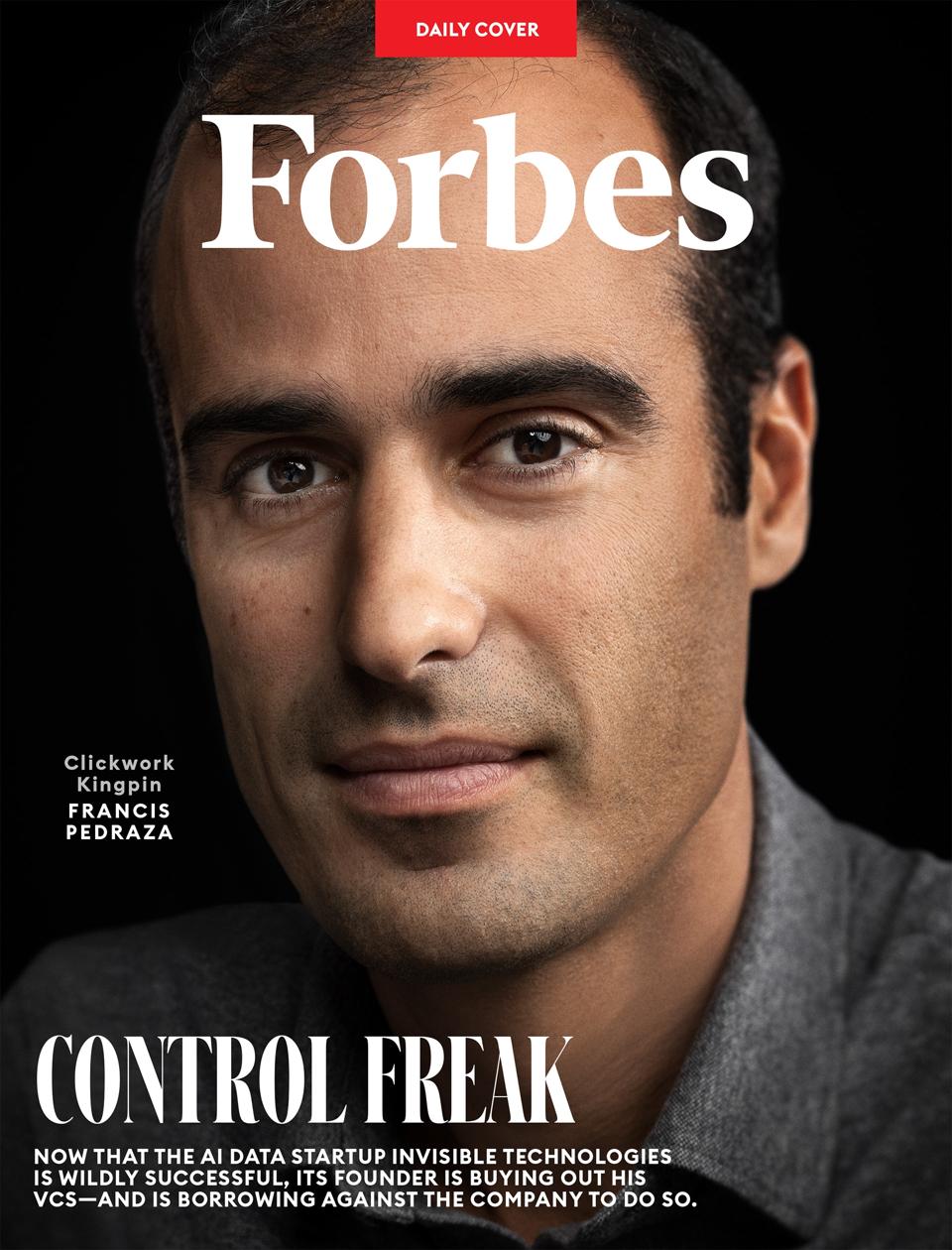

Now that the AI clickworker startup Invisible Technologies is wildly successful, its founder is buying out his VCs – and is borrowing against the company to do so.

In early 2020, Francis Pedraza was staring squarely at failure. For more than four years, the Cornell grad had been trying to combine AI and platoons of remote workers to help businesses scale fiddly projects like screening résumés, manning chatbots or rewriting product descriptions—repetitive tasks that remained just slightly too complicated to fully automate. But uptake had been slow, and venture capitalists had been reluctant to invest. Services businesses like his Invisible Technologies were horrible investments, per Silicon Valley lore. Hard to scale, hard to run, hard to defend. Hard pass. Invisible had lost four of its cofounders and had to go back to its few loyal angel investors for more money. Then, in March 2020, DoorDash called.

The food delivery company told Pedraza it needed help, fast. The pandemic’s global lockdown measures would more than double demand for takeout orders to $51 billion that year. DoorDash was in a race with Uber Eats and Grubhub to find and sign new restaurants. Specifically, it needed assistance with the messy business of importing menus and pricing. The outsourcing shops that had typically done this work were now shuttered.

It was the deal Pedraza had been looking for. “I hate operations because it’s friction all the way down, but that’s why people buy it,” he says.

Two years later, he got another call from a business struggling with an even bigger data problem. OpenAI wanted Invisible’s help hammering the hallucinations out of what would become the model underlying ChatGPT. Contracts with Amazon, Microsoft and AI unicorn Cohere followed, helping skyrocket Invisible’s revenue from $3 million in 2020 to $134 million last year, on which it made a profit of $15 million (Ebitda).

AI training has quickly become a crowded field with clickworker factories like Scale, Surge and Turing vying for the same jobs. But while Scale, living up to its name, raised $1 billion at a $14 billion valuation last year on $1 billion of annualized revenue, Pedraza, 35, is deliberately plotting a different path for Invisible, which claims to be remote (it’s incorporated in Delaware; Pedraza is mostly based in New York City). The company raised only $23 million from investors—including VC shops Day One, Greycroft and Backed—a drop in the bucket given the ongoing AI frenzy. And rather than selling off chunks of equity to more VCs, Invisible has been buying back its shares. “We could not be more different,” says Pedraza, who retains an estimated 10% stake in the business, which was last valued at $500 million in 2023. (He generously granted the vast majority of shares to 300 or so of Invisible’s current and former staffers, whom he calls “partners”—collectively, they own 55%, or around $1 million apiece.)

Pedraza has borrowed $20 million over the last three years (first from a New York growth fund called Level Equity, more recently from JPMorgan) to buy out his early investors. “I believed that our equity would 10x in value, so it was an amazing arbitrage,” he says.

It’s a bold move, and unusual among VC-backed startups. Is paying interest (effectively as high as 20% in the case of the Level Equity loan) the best use of Invisible’s limited funds? “You’d have to be confident to put on a big stack of debt just to lower people’s dilutions,” says David Wanek, CEO of one of Silicon Valley’s oldest debt funds, Western Technology. And wouldn’t that money be better spent on growth rather than effectively increasing Pedraza’s stake? That decision was a no-brainer for Pedraza. Turning employees into (small) owners was his shortcut for high growth on a low budget.

A $500 million valuation (over three times revenue) seems modest for a service company, but shockingly low for an AI firm. When Pedraza bought out his “passive” investors in 2021, he wasn’t just the only buyer—he also got to set the $50 million price. “It was a good outcome for everybody, but the incentive was to keep the valuation low,” he says.

Angel investor Edward Lando was one such seller after writing one of the first checks to Invisible at a $5 million valuation a decade ago. “The company keeps doing really well, and I often wish I hadn’t sold part of my position,” he says.

Pedraza thinks it’s a win-win. He gets more control. His early VCs—who long ago probably wrote their investments down to zero—get a clean exit.

An easy exit is especially appealing because Pedraza has been vocal about his intention never to sell Invisible or IPO early. “You don’t need to sell the company or go public, and that gives you more freedom,” he says. VCs might also be eager to take the cash and lose the sophomoric posturing. Pedraza’s rambling business updates are larded with references to Daoist philosopher Laozi, Napoleon and Ronald Coase, the Nobel laureate economist. “He’s a visionary,” says one clickworker who was recently let go. Former investors are more skeptical. “It’s intellectual masturbation,” says one.

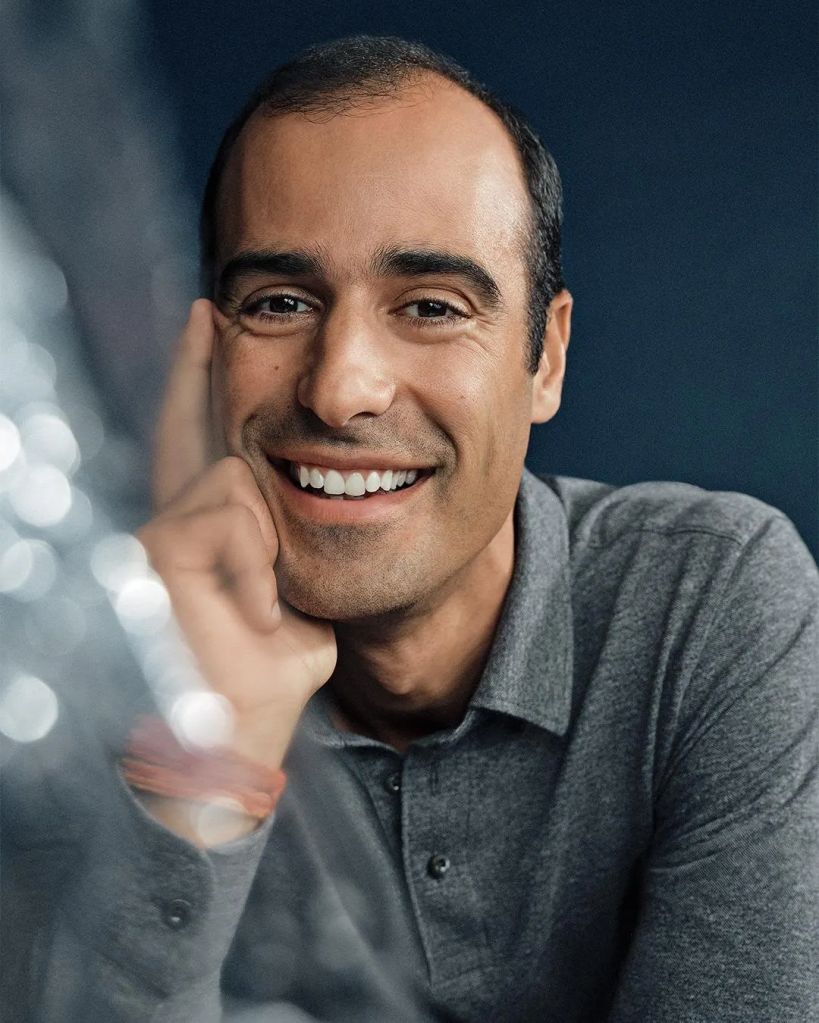

“There will always be some things humans are better at.”

Francis Pedraza, Chairman and founder of Invisible Technologies

Invisible is not Pedraza’s first rodeo. At Cornell, he spent a summer at Google slinging ads and realized he wanted to start his own business rather than slog up the corporate ladder. His first idea was Everest, a goal-setting app. He parlayed an airport meeting with a Peter Thiel acolyte into an audience with Thiel himself and, eventually, modest backing from the billionaire PayPal godfather. The project raised $2.7 million and sparked an initial flurry of interest. Pedraza ground away at it for three years before shutting it down in 2014 due to an inability to retain users. “I wasted a few years of my team’s lives. It was more than a decade of human time and energy,” he says ruefully.

He atoned with a penitent march along Spain’s 500-mile Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route. Back in San Francisco, a new idea struck him. A forest of apps and software had sprouted claiming to solve virtually every problem, but many business tasks remained painfully manual. Throwing employees at bottlenecks worked but was expensive and caused headaches for management. Pedraza raised $500,000 in 2015 to start a company that could bridge the gap. “Honestly, it was just a bet on Francis,” says Masha Bucher of Day One Ventures, who invested $175,000.

Pedraza’s initial idea was that platoons of remote workers, and AI, could serve as super-secretaries helping busy executives book meetings and flights. That was a bust. “We were spending $20,000 to make $10,000,” he says. He realized that time-strapped executives, most of whom already had competent human assistants, weren’t his user base after June, a San Francisco–based startup that makes digital ovens, started using Invisible to take over the time-sapping work of finding, screening and scheduling calls with new hires. Pedraza started to hunt for other annoying and hard-to-automate jobs like reviewing insurance claims for health company Headway, or cleaning Nasdaq’s data. In other words, exactly the type of drudge work that corporates have outsourced for decades to offshore teams from the likes of Accenture, Cognizant and Infosys. Some jobs were parceled out to remote workers; other, simpler tasks were automated by Invisible’s engineers.

“The most capable models will be those that integrate artificial intelligence and human intelligence into one solution,” Pedraza says. “There will always be some things humans are better at.”

As he slowly reestablishes himself (and his employees) as the sole owners of Invisible, he has suitably ambitious plans. Target one: Accenture and its fat $245 billion market cap. Pedraza is betting that his clickworkers are not only smarter and cheaper but that Invisible’s inside track on AI training will help him automate tasks faster than Accenture. Pedraza’s latest hire, Matthew Fitzpatrick—who formerly led McKinsey’s AI lab—will lead this. “There’s an opportunity for us to compete on their territory, which is going after $50 million to $100 million enterprise deals,” Pedraza says.

Landing deals of that scale would make Invisible’s current contracts look like table stakes. And if everything goes according to plan, Pedraza—and his very lucky employees—won’t have to share the pot with anyone.

PAY IT FORWARD

Francis Pedraza might be America’s most generous boss. He has given 300 or so of Invisible Technologies’ current and former staff 55% of his startup, a stake worth some $275 million. Bad for Pedraza’s pocketbook but great for motivation. “Everyone is working harder because they own more,” he says. Here are some other benevolent bigwigs.

Donald Friese

When the rag-to-riches billionaire sold glass industry supply business C.R. Laurence in 2015 for $1.3 billion, he gave $85 million of his take to every employee who had worked there longer than a year. Everyone got at least $5,000; some got more than $1 million. “It was only fair that I should share,” Friese told Forbes in 2015.

Mark Cuban

The serial entrepreneur says he always gives employees a cut of his windfalls. His $5.7 billion dot-com-bubble deal to sell Broadcast.com made 300 of his 330 employees millionaires. Dallas Mavericks staffers got $35 million when he offloaded a majority of the team in 2023, almost as much as superstar Kyrie Irving earned that season.

Sara Blakely

The shapewear billionaire celebrated selling a majority stake in Spanx to Blackstone in 2021 by treating her employees to two first-class tickets to anywhere in the world and $10,000 of spending money to stuff into their suitcases.

Hamdi Ulukaya

The billionaire Turkish immigrant behind yogurt giant Chobani made his 2,000 or so workers a sweet deal in 2016, dishing out 10% of the private company’s equity to them, based on seniority.

This story was originally published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.