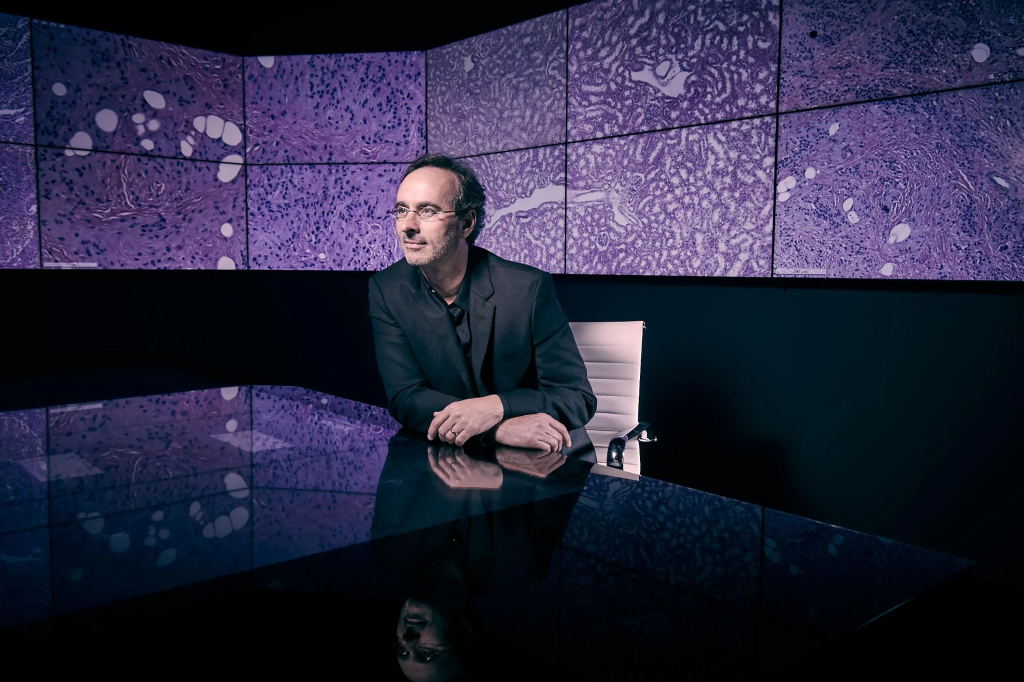

After a quarter century as a serial entrepreneur, Eric Lefkofsky wants his latest unicorn, health tech firm Tempus AI, to be the “enduring legacy” of his career. Here’s how he hopes it will dramatically change millions of patients’ lives.

This story featured in Issue 14 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Walking through health technology firm Tempus AI’s midtown Manhattan office, Eric Lefkofsky brushes past stick-straight fronds of snake plants in neatly arranged planter boxes and employees chatting over lunch in the open-floor-plan space which, unlike the company’s Chicago headquarters, doesn’t have an actual laboratory. In his signature oval glasses and a navy button-down, the billionaire walks into a nearby conference room, doesn’t bother closing the door and skips the small talk.

“I tend to be very singularly problem-focused,” the Tempus founder and CEO says, swiveling in his chair. “I get consumed by it, and then don’t spend time thinking about anything else.”

Those who’ve worked closely with Lefkofsky agree: In one-on-one meetings with him, he only wants to hear the bad news, right to the point. If a one-on-one “lasted more than five minutes, you knew you were in trouble,” says Gary Palmer, Tempus’ former chief medical officer. Tempus’ former chief scientific officer Joel Dudley adds, “If you tell him, ‘Hey, this is going well,’ he’s like, ‘Who cares? Tell me what’s going wrong,’ which was weird at first, but that created a culture of candor that was very healthy.”

Lefkofsky never imagined he’d end up here, nine years into helming a health tech company he founded. Even after starting companies in the disparate industries of apparel, printing, logistics, media and, most famously, e-commerce, with Groupon, he’d insisted to himself that he would never create a healthcare company.

The industry was too regulated, he reasoned. Then, in 2014 his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer. He was puzzled at how little data permeated her care. He spent a year talking to oncologists, and then, despite having no healthcare background, founded Tempus in 2015. The firm began as an oncology-focused data company, sequencing cancer patients’ tumor samples and analyzing them with AI models to help determine a more accurate diagnosis and personalized treatments. It’s now expanding to some psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, ADHD) and cardiology with a broad goal to apply artificial intelligence to “all disease areas globally.” And it’s licensing parts of its dataset to pharmaceutical firms like AstraZeneca and researchers at such places as the Mayo Clinic.

Lefkofsky took the now 2,300-person company public this summer at a valuation of $6 billion, renaming it Tempus AI when he did so. It generated $600 million in revenue in the year through June, but isn’t yet profitable. Net loss for the period was $720 million, more than half of which was an accounting loss tied to converting preferred stock to common stock at the IPO.

Since then, its share price has increased by 22%, giving it a market cap of $7.6 billion. Lefkofsky’s stake is worth around $2.5 billion, accounting for more than half of his $4.4 billion net worth and landing him on The Forbes 400 list of richest Americans this year for the 12th time.

“You have to convince me why I shouldn’t back this guy,” says venture capitalist Peter Barris. He first invested in Lefkofsky’s printing company InnerWorkings in 2005 while he was a managing general partner at New Enterprise Associates. “In my 30-plus years in venture capital, he is the best entrepreneur I have ever dealt with.” One of Lefkofsky’s biggest supporters, Barris has invested in every Lefkofsky company since, touting his ability to experiment with different ideas in “rapid-fire succession” and quickly let go of the ones that don’t work until he finds the one that does.

On top of Lefkofsky’s obsession with solving problems, employees, business partners and investors say he has built so many successful businesses because he is decisive, detail-oriented and almost overconfident—which also makes him one of the best salespeople they’d ever met. But Tempus is different and could signal the end of Lefkofsky’s streak as a serial entrepreneur. He hopes it will overtake Groupon as the “enduring legacy” of his career. Not only is this the first company Lefkofsky has founded alone, it’s also by far where he’s spent the longest as CEO. Before Tempus, he’d only really been CEO of a public company once—at Groupon, in an interim, co-CEO role after its board (which Lefkofsky chaired) fired Andrew Mason.

“When I decided to start Tempus, I knew that I kind of never again wanted to not be the CEO,” he says. “I like making calls. I like being responsible if it goes right. I like being responsible if it goes wrong.”

Born in West Bloomfield, Michigan, to an engineer and a teacher, Lefkofsky was the youngest of three, all of whom went to the University of Michigan. Lefkofsky realized as a freshman that he had a knack for business when he began selling carpets to college students and made $100,000 a year doing it, according to a blog post he wrote in 2012. His early track record followed a pattern more akin to venture capital than to “typical founders”: have an idea, build a business, cash out, move on—all at warp speed.

“I have never been afraid to act. It is one of my greatest strengths in business. When I have an idea or reach a conclusion, I act on it, immediately and without reservation,” Lefkofsky wrote in the blog post.

In 1999, Lefkofsky and his law school classmate Brad Keywell moved to Chicago and founded early internet company Starbelly, scaled it at an astronomical pace and sold it nine months later for $240 million to a company that soon went bankrupt.

For the next few years, it seemed like each new problem Lefkofsky faced quickly led to a new company centered around fixing it. In 2001, he cofounded InnerWorkings to help him print and ship books and magazines. After having trouble “finding the trucks to deliver the stuff,” Lefkofsky and Keywell started Echo Global Logistics in 2005. A realization that a lot of Echo’s marketing materials were used by media buyers led to MediaBank in 2006.

Then came Groupon, after one of Lefkofsky’s InnerWorkings employees, Andrew Mason—who would be in the office even before Lefkofsky arrived around 5:30 a.m—pitched an idea based on collective e-commerce. Lefkofsky and Keywell seeded the company, with Lefkofsky contributing $1 million. Groupon’s meteoric rise culminated in a $13 billion IPO in 2011 and put Lefkofsky on The Forbes 400 for the first time. But Groupon struggled to make money, and its share price quickly cratered. It now trades at less than 5% of that market cap, and a majority of its board members, including Lefkofsky, resigned last year.

Along the way, Lefkofsky and his longtime business partner Keywell leaned into being investors, setting up venture capital firm Lightbank, which now has more than $700 million invested in nearly 100 companies.

From the beginning, Tempus has been a departure from everything this serial entrepreneur had subscribed to throughout his first two decades in business. Twelve years ago, he wrote that he was “unlike typical founders,” for whom “monetary success is an afterthought and the attachment they develop toward the company is … no different than a parent’s attachment to a child.” This time around, Lefkofsky says a personal passion fueled Tempus: “Building a business is like raising a kid,” he told Forbes last month.

At first, he says he wasn’t even sure whether Tempus would be a company or a nonprofit, so he largely funded the business himself early on with some $100 million, a combination of personal cash and an investment from his venture capital firm Lightbank. “I was afraid that it might not make anyone any money,” Lefkofsky says.

Lefkofsky has always been profit-minded. Olufunmilayo Olopade—a renowned oncologist at the University of Chicago and founding scientific advisor to Tempus who worked on a paper that used Tempus data to analyze differences between African American and European American populations—remembers asking him to donate money to help with research. “He said, ‘why would I give you $50 million when I can start my own company” to solve the issue for every university and hospital? Lefkofsky doesn’t remember saying this but agrees that at the time he believed that a for-profit entity was needed in order to bring the benefits of technology and AI to healthcare.

Olopade also recalls Lefkofsky being “consumed” with figuring out how cancer worked and why there was so little data to inform and personalize a treatment plan. In Lefkofsky’s words: “I was just completely fixated on understanding everything, and I understood nothing.”

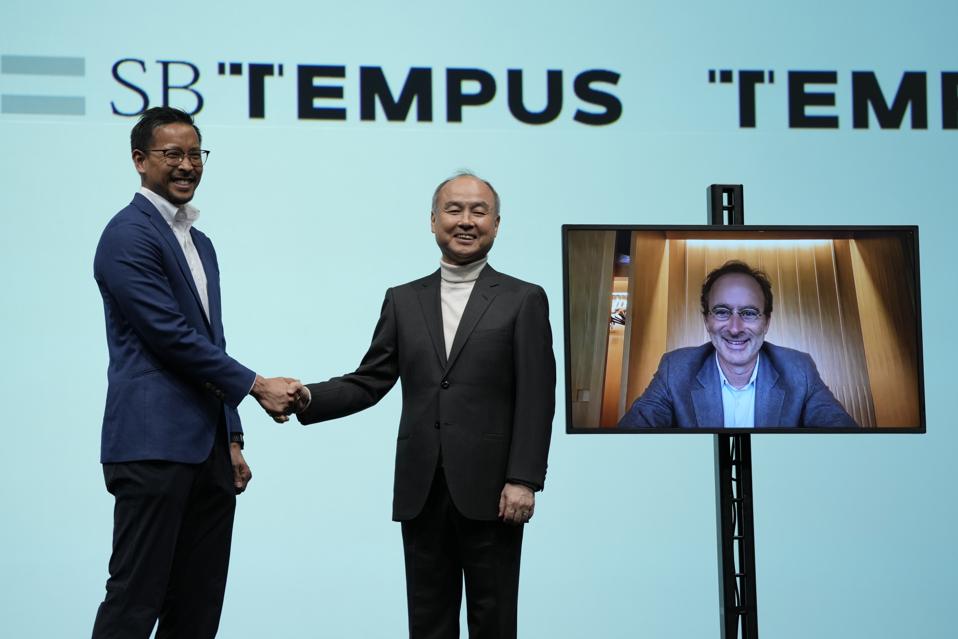

That soon changed. As Tempus grew, Lefkofsky says he made sure to do “pretty much the opposite of what had failed before.” The company scaled more slowly, and stayed in one country—the United States—for much longer. (Tempus entered its second country, Japan, earlier this year via a $200 million joint venture with SoftBank; Groupon, meanwhile, was in some 50 countries by its third year.) Lefkofsky is no longer “multiprocessing” as much, as Barris put it; per an SEC filing, he spends “virtually all of his professional time” with Tempus. After 25 years of building businesses together, Lefkofsky and Keywell stopped working together in 2019, when Keywell resigned from Tempus’ board. Tempus also waited much longer to go public, nine years compared to the four or five in Lefkofsky’s three other IPOs. And aside from Pathos, which he cofounded in 2020 and does similar things to Tempus but with drug development instead of diagnostics, Lefkofsky hasn’t started any new ventures in a decade. (Tempus owns 20% of Pathos, and they share data and a C-suite executive.)

While the pace was much slower than what Lefkofsky was used to, some healthcare veterans didn’t feel the same. For all the talk about growing “slower,” though, Tempus still expanded rapidly for a healthcare company, per former chief scientific officer Dudley, who is now a full-time healthcare investor at Google billionaire Eric Schmidt’s Innovation Endeavors. In part, that was due to Lefkofsky pushing his employees via at-times “unreasonable” expectations, one side effect of having a software guy trying to do healthcare, Dudley says. Lefkofsky would ask for a project to be done in three months, for example, that would typically take a year. Everyone would think he was crazy, until they got it done in six months—much faster than they’d expected.

Tempus gets a bit more than half of its revenue (55% in the first half of 2024) from genetically analyzing patient samples sent by doctors and hospitals. A doctor using Tempus might find a tumor in a patient, then send a little slice of it to one of Tempus’ labs in Chicago, Atlanta or Raleigh for genomic sequencing to help explain the specific gene mutations driving tumor growth. Tempus then analyzes the results with its 200-petabyte machine-learning-trained dataset of similar patients’ lab tests (patients’ names and other identifying information are not linked in the data) and clinical data. Then Tempus sends a report to the doctor with the test results, a list of suggested treatments and links to related research, with the goal of helping arrive at a more accurate diagnosis and a personalized treatment plan for the patient. After the process, Tempus removes the patient’s identifying information from the data it generated and adds it to its dataset. In 2023, Tempus sequenced 288,000 patient samples, up from 63,000 in 2019.

The remainder of Tempus’ revenue—about 45%—comes from licensing its massive trove of data for research use, particularly to help with clinical trial design, drug discovery and drug development. Nineteen of the 20 largest pharmaceutical companies in the world license slices of Tempus’ 200-petabyte dataset paying anywhere from $150,000-$500,000 (per a JPMorgan analyst report) to hundreds of millions of dollars. On the upper end, Tempus has five-year contracts with AstraZeneca (through at least 2028) and GlaxoSmithKline (through at least 2027) worth up to $300 million each. Certain biotech firms and university research centers also license Tempus’ data.

Tempus was a pioneer in combining these two revenue streams under the same company. Between the two, it works with approximately 50% of U.S. oncologists, up from 30% five years ago. That—combined with Lefkofsky’s aggressive networking to partner with large cancer centers, like Olopade’s at the University of Chicago, and biopharma firms around the country to exchange data—allowed Tempus to grow as quickly as it has. And while Tempus is not yet profitable, the two-prong approach helps there too, as its data & services segment has higher margins than the genomic sequencing, which may be difficult to expand in a large-scale way to non-cancer disease areas, per analyst Bruce Quinn. Another largely untapped area could be figuring out how to more aggressively monetize its actual AI algorithms, which currently only generate around $1 million in revenue per quarter, though Olopade cautions that AI cannot simply solve disease. “There’s a lot of hype that AI is going to deliver, but until we have good doctors making good judgments, a test is just a test.”

Tempus’ path forward is not going to be easy. It competes with several large competitors—including Foundation Medicine and Flatiron Health (both purchased by pharma giant Roche for a combined $4.3 billion in 2018), as well as Guardant Health (which went public in 2018 and has a $2.7 billion market cap) for access to patient data from hospitals and pharmaceutical companies and the same lab samples from doctors who can independently choose where to send them. Oncologist David Agus and Olopade, who are both scientific advisors for Tempus, say they have worked with both Tempus and Foundation and don’t see a huge difference between the sequencing results. Tempus is different thanks to its ability to layer additional similar patients’ information like imaging data and patient records on top of the test results, Bank of America Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Ryskin wrote in a note.

Tempus is currently involved in two lawsuits with Guardant over intellectual property. For the first, Guardant sued Tempus, alleging patent infringement for some of Tempus’ liquid genomic tests (the complaint was filed some five years after Tempus started using the tests). In the second, Tempus sued two of its former employees, alleging they downloaded trade secrets for use at their new jobs at Guardant. “We are confident we have strong defenses against the frivolous claims and ultimately, our focus remains on patients,” a Tempus spokesperson wrote to Forbes.

Additionally, Tempus’ Chicago lab staff unionized in March over concerns about better patient care, staffing levels and safer working conditions—the first time an AI company has successfully unionized—with negotiations set to start this month. “People felt like they were bringing issues to management and not getting listened to,” says Tempus employee and union bargaining committee member Anson Poe, emphasizing the union’s desire to improve burnout and decrease turnover. Poe noted that management has been listening better since the union organizing started in 2022. Per Lefkofsky: “I don’t have a strong opinion on whether people should unionize, but we’re happy to negotiate.”

Challenges and skeptics aside, Tempus is projected to be profitable (on an adjusted EBITDA basis) within the next year, Lefkofsky says, with plenty of room to grow. It’s playing in a “very large sandbox” that is the intersection between artificial intelligence and healthcare, per Barris. “Who’s the next Google, the next Amazon? I think it will come from this space.”

Lefkofsky, of course, agrees, saying that there will be several big companies in genomic sequencing, big data and AI—and Tempus is swimming in all three of those lanes. “I do hope that Tempus is the enduring legacy of my career,” he says. “It has the potential, unlike anything that I’ve ever built. …. There was never a moment in any company I was ever at where I’m like, this could be as big as Apple.”