The Rolex Sydney Hobart is probably seen live by more people than any other sports event, bar the Tour de France. Stewart Hawkins talks to Matt Allen and James Mayo, two race veterans who are strongly tipped to win this year’s race about the romance that surrounds what is arguably the toughest ocean race of them all.

This story featured on Issue 14 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Another storm brewing: I hear it sing i’ th’ wind. Yond same black cloud, yond huge one, looks like a foul bombard that would shed his liquor. If it should thunder as it did before, I know not where to hide my head.” – William Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

It’s uncomfortable, it’s tough, it takes you away from your family around Christmas time and puts you seriously in harm’s way. It’s expensive, fraught with complications – technical and navigational – you’re at the mercy (or mercilessness) of the sea gods, and it can be damned dangerous. So why do it? And an even more compelling question, why do it more than once?

We’re sitting in Matt Allen’s surprisingly homely Sydney harbour-view apartment surrounded by the detritus of his various senior roles in global sport. Files, reports, and papers spill from his desk, and hung on the walls are the wooden models of the hulls of boats he has raced. The effect, though, particularly given we’re meeting on a grey-sky day with a storm threatening, is more Prospero’s library than eccentric professor’s – there’s an orderly disorder to the place – purposefully lived in, probably describes it best.

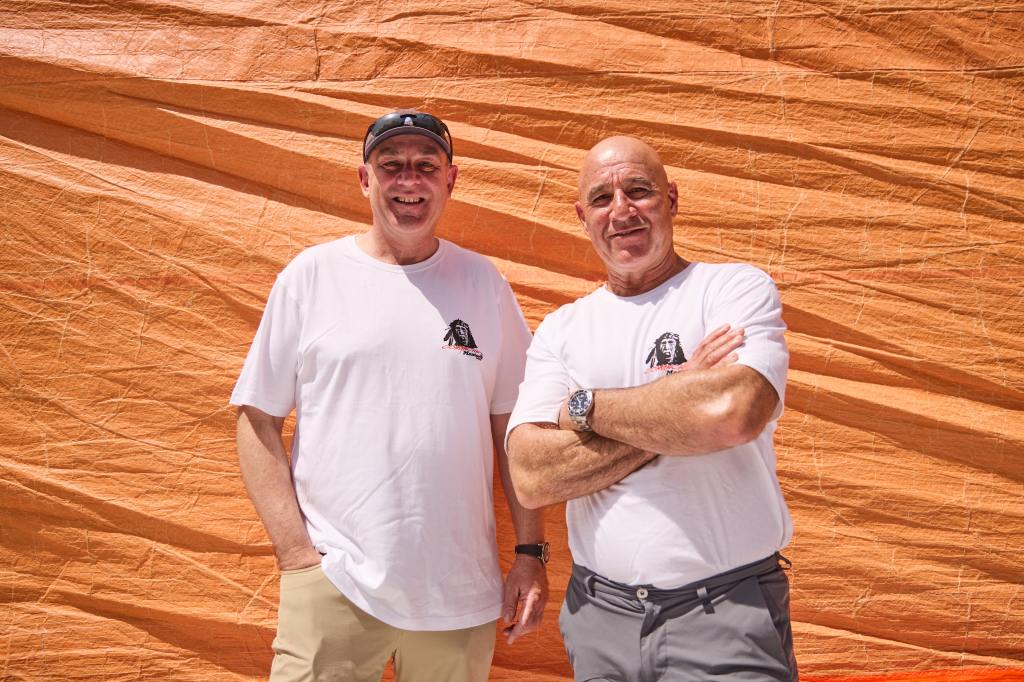

Allen’s provenance is impressive; former commodore of the CYCA, Australian Olympic Committee Vice President and Vice-Chair of World Sailing’s Oceanic and Offshore Committee, he has also sailed the Rolex Sydney Hobart 31 times and won it four times. This time, he is co-skippering the 100ft Master Lock Comanche (sailed by John Winning under the name Andoo Comanche last year. It was pipped at the post in a dramatic finish by another 100-footer LawConnect.)

“I think it’s the most interesting yacht race in the world,” Allen responded in his characteristic understated way when asked the elephant-in-the-room question. So, I took a different tack. What scares you the most about it?

You’ve heard the expression “howling wind”? Allen talks about the “screaming wind”.

“1984 was one of those really bad races where not many boats got to Hobart; the wind was screaming. You might never have heard it, but I’ve heard it about three times in my life,” he says.

They were about 80NM south of Sydney amid a “classic southerly” with very steep waves. “I was down below, and we launched off one of those [big] waves and the frames in the bow of the boat, carbon frames, five out of six, broke. I saw this almost dematerialise before my eyes, and we had broken carbon fibre everywhere. I thought the boat was going to break in half. I just screamed on deck, ‘turn the boat around’.”

Allen says one of the biggest challenges of the event is the “racetrack” itself.

He sees it as a fine balance to ensure you’re pushing hard but not so hard that you break something and then have to slow down.

“A number of years, we’ve been on the right or wrong side of that,” he admits.

“The coast of New South Wales is very affected by the East coast current, so the tactical side of that is always quite interesting. Where do you want to go for the current? How important is the current versus what’s happening with the wind? Depending on the weather, sometimes you’re a long way out because often in the southerly, you can get a left shift as you approach Tasmania.”

Adding to the challenge, Allen says that after all the drama of the open water, by the time you get to the River Derwent and Storm Bay, you can become becalmed, and even if you’re winning the race as you enter those waters, you could be 10th by the time you reach the finish line.

“You can come in sometimes, and it’s the most beautiful sailing breeze. And other times, you can sit there for half a day trying to get across the finish line in a small boat. I’ve often said, you’ve got to have the right boat, you’ve got to have the right crew. But then you’ve got to have a bit of luck as well in that final stretch of the race. A lot of people go, oh, that’s a bad thing for the race. But in a kind of a way, it’s a good thing. It creates a bit of intrigue.”

This was evidenced by the finish of last year’s event, where LawConnect snatched line honours in the closest end to the race in four decades. Comanche was in the lead going into the Derwent only to have LawConnect, skippered by Christian Beck, take advantage on the last gybe.

Allen’s co-skipper is James Mayo (Director of Mayo Hardware), who last did the course in 1987 – when the boat he was on, won both line honours and on handicap – and he had his reasons for returning to the iconic race – many of them had to do with the availability of Comanche.

“On a big race craft,” he says, “the decisions have got to be good, calculated, in-time and in-flow so that you don’t get caught out with too many sails up and heading in the wrong direction.

“[That boat has] had such an amazing track record, and for me, it’s like a racehorse. If you’ve got it under control, you’re going to go well, but if you’ve lost control of it, how the hell do you get it back in control?”

He not only has every intention of winning the race, he’s also out to break the race record and is adamant he and Allen have the team to do it.

“They’re battle ready because a lot of these guys sail on a hundred footers in other parts of the world. So if it’s in Bass Strait and [the wind’s] 60 knots or 70 knots, these guys have seen it before.”

Intriguingly, when asked who he thinks his main competition will be, Mayo answers, “Ourselves”.

It’s such a technical challenge that what he’s talking about is the preparation of the boat, the crew, the sails, the engines, the hydraulics, the maintenance and then, slightly esoterically, he speaks about “how we respect the boat”.

More prosaically, he cites LawConnect as being the biggest challenge for line honours. “Obviously [the] LawConnect [crew are] an incredible bunch. I’ve sailed with some of those guys. They are a great bunch of sailors with a huge amount of experience. I have the absolute utmost respect for them, and they did it last year. Never underestimate,” he says.

“But the ultimate goal has to be that THAT record has to be broken.”

“Ships are but boards, sailors but men” – Merchant of Venice… or are they still?

Like F1 and other big-money sports, technology in yachting is evolving fast – changing the face of racing globally – probably most dramatically with the introduction of F50 foiling catamarans in SailGP in recent years. The technology in the right conditions allows the boats to exceed 50 knots.

When asked if we would ever see a hydrofoil boat compete in the Sydney Hobart, Allen was certain the time would come – with the caveat that the route is not “the perfect racetrack” for that kind of vessel, with one of the biggest problems being wind angles.

“It’s a north-south course,” he says, “but we’re going to see it. We had, was it 2016? A good-reaching wind coming across the boat, so more of a westerly type breeze. And that’s an example where a foiling boat would obviously do well; [foiling] is around the corner.” The other thing that’s coming is increasingly boats driven by computers, Allen says.

Today’s computers can steer a compass course or steer to wind angle, but what is evolving quite quickly is having autopilots with AI and the ability to see the waves and wind with LIDAR [Light Detection and Ranging] technology. “Using AI to steer the boat, it won’t get tired at three o’clock in the morning,” Allen quips.

But for the moment, the rules of the race only allow conventional autopilots for double-handed boats, and while the technology used on some of the vessels is the equivalent of anything in Formula 1 – something which, ultimately according to Allen, adds to the appeal.

“There are four 100-footers in the race, but it’s really a showdown between LawConnect and Master Lock Comanche.”

Matt Allen, race veteran

Prestige & tradition

In March this year, Rolex re-signed as naming rights race sponsor for another 10 years on top of the 20-year relationship the company already had with the event.

It’s an extraordinarily long and consistent corporate relationship by any measure, and the current CYCA commodore, Sam Haynes, explains the appeal of the event:

“It’s a 600NM race, so it [has] an in-built challenge in the length and the track between Sydney and Hobart – it’s a true test,” he says.

“It’s an internationally renowned race [and] one of the most famous races [in the world]. It’s definitely the most watched start and, overall, the most watched race that happens anywhere.”

Haynes says this year’s 79th edition of the race will feature a lot of double-handed boats and opines that a double-handed team could well “win this race one day given the right conditions.”

“It depends on your weather windows, but there are quite a lot of those boats which are very competitive. So those are [one] of the things to look out for.

In the commodore’s opinion who then is looking good to win? He wouldn’t be drawn, saying it’s “so wide open depending on the weather.” Matt Allen was prepared to be a bit more specific: “There are four 100-footers in the race, but it’s really a showdown between LawConnect and Master Lock Comanche. It’s a matter of which boat is going to perform. What are the weather conditions? The boats are moderately different, but there’s no Blackjack, no Wild Oats, there’s no Scallywag. It’s going to be a rematch of last year’s and for the crew on our boat that were on the boat that got beaten last year, it is a lovely opportunity for them to roll the dice again.”

Skilfully lucky

There’s a compelling argument that the very fact that the race is so unpredictable, so much a “human endeavour” with all the vagaries and pitfalls that entails, is what makes it so compelling.

Allen closes our discussion with an anecdote demonstrating just that:

“It’s 1983. I’m 21 years old. I was the boat captain, which means I was in charge of the mechanical side of running the boat systems maintenance. We’d sailed a really good race down to Tasman Island. And we got round at 11 o’clock at night, and we were leading the race by a long way. There was no wind. Over the next few hours, we could just see more lights come, so all the boats behind us were catching up – you could see their port and starboard lights. It was hugely frustrating. We had the race won. I looked and there was just this bit of breeze on the water. You could see the ripple on the surface just in a bit of moonlight. I said to [the bloke] who was driving, ‘Just over there, get over there.’ And he goes, ‘shit, there’s wind there’. Everyone else had given up, and then the front of the boat just got into the breeze.

“That breeze; it never got to the boats that were a hundred meters behind us or if it did, it was about four hours later. We won the race, lost it, and won it again.”

Was it luck or skill?

“There was skill,” he says. Then pauses, and adds: “and there was luck”.