A grandfather and grandson teamed up to tackle the lethal global problem of antibiotic resistance, inventing a new class of drug in a Perth garage, and now getting it into phase-3 trials.

This story featured in Issue 13 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

The minor scratch had festered, and a red line was streaking up the leg of a retired fund manager now known in the scientific literature as “Patient X”.

The bacteria causing the ulcer were not responding to antibiotics, so Patient X was facing a long stretch in hospital, painful debridement, acute care and, in the second-worst-case scenario, amputation.

But Patient X, 71, had experience in the med-tech space. He started researching what was out there. He saw that antibiotic-resistant bacteria, so-called “superbugs”, were predicted by the UN to kill as many people as cancer by 2050. He looked at ASX-listed Next Science, which seemed to be doing interesting things with “biofilms”, but then came across another ASX-listed company, Recce Pharmaceuticals, which claimed to have an antibiotic that was resistant to resistance.

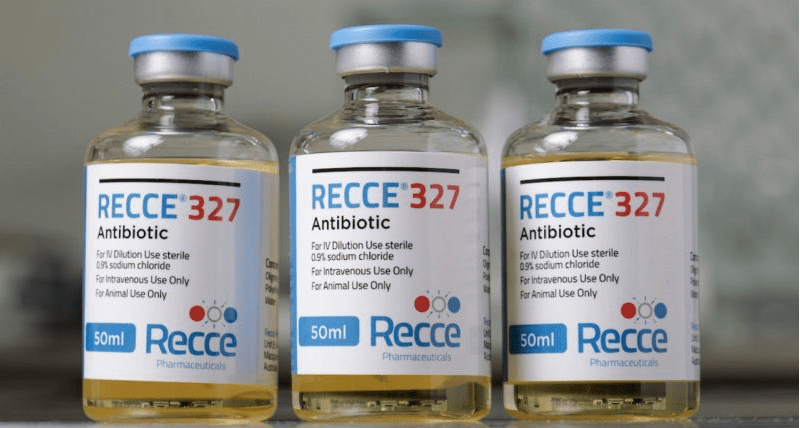

“I realised you could access it through the TGA’s [Therapeutic Goods Administration] special-access scheme,” Patient X tells Forbes Australia on a phone call, asking that we respect his medical confidentiality. He got his doctor to fill in some forms and was delivered a tube of clear gel. Without realising, as he dabbed it into the angry red hole in his ankle, he had become one of the first humans to use Recce Pharmaceutical’s formulation, R327.

“A day or so later, we took the gauze off to dress it,” Patient X says. “And the damn thing had just about cleared up. It was unbelievable.” His wife took photos and put more gel on. When they looked next, it had healed some more, and all that was left was a hole where the infection had drilled into the bone. “I can’t think of sufficient words to describe it,” he says. “It disappeared almost like a magic wand.”

Patient X did what any self-respecting retired fund manager would do; he bought Recce [ASX: RCE] shares. When he visited orthopaedic surgeon Dr Andrew Wines, who he was seeing about another issue, Wines asked how the infection was going. Patient X lifted his leg and pulled down his sock.

“I’d never seen anything like it,” recalls the doctor. “And I look after a lot of patients who get ulcers and things. It piqued my interest, so I looked at their webpage and saw the preliminary data, and I thought, ‘Wow, this seems amazing’.”

Wines went on to use R327 with other patients under the special-access scheme and saw consistent results fixing a variety of ailments, including infections around the site of prosthetics and bone infections [osteomyelitis] – the most intractable of chronic bacterial infections and the bane of orthopaedic surgeons. Wines is now working with Recce to organise a randomised controlled trial on such bone infections.

He did not buy shares. It would be a conflict of interest, he says. “But if I weren’t recommending it to patients, it would be a sensible investment because I think it’s got a lot of potential.”

More than 100 people have now been dosed with R327, showing promise in solving the growing resistance of deadly bacteria to antibiotics. It has undergone Phase-2 trials in Australia and is in a Phase-3 trial in Indonesia. Recce is seeking approval to commence Phase-3 trials in the US, having received a $3-million grant from the US Department of Defense.

It’s been an extraordinary journey for a company that started in a Perth garage in 2012, when a then 22-year-old entrepreneur, James Graham, dropped in to visit his 78-year-old entrepreneur/inventor grandfather, Graham Melrose.

Melrose had invented No More Tears shampoo for Johnson & Johnson. He’d reformulated their baby powder when fears arose that it was toxic. He’d gone corporate and consulted on marketing matters, then started an ag-tech company, Chemeq, that was an ASX star in the early 2000s, selling a prophylactic animal feed, but which went belly up three years after he left it – losing him $180 million in the process.

“He lost his life’s work,” explains Graham. “Never sold a single share and went down with the ship. This is somebody who had a brilliant product, and through no fault of their own, it’s completely gone to shit.”

Graham says many others lost a lot, too, in that 2007 Chemeq failure, and it weighed on his Pop. He’d become reclusive, so Graham would drop in to his Perth home as often as he could.

“What are you up to, Pop?” Graham asked that day in 2012. “I’d love to see if we could

create a company together.”

Melrose went to his garage laboratory under the stairs and pulled out a vial. “I think this has antibiotic properties. Maybe we should do something with it.”

James Graham, now 34, had never been academic. He didn’t get an ATAR at high school but managed to get into university with a TAFE qualification. “I went to university to get a piece of paper. My dad [Stewart Graham] invented CommSec’s stock trading system [through

a company called Min-Met] and had a bunch of other successes over the years. Still, he always said, ‘If only I had a piece of paper, people would have believed me earlier’.”

“My grandfather would tutor me twice a week. He was effectively hiding from the media and the public – people had lost a lot of money. There were court cases. He was never in trouble for

anything, but I watched him become a recluse. Under the stairs was his little laboratory. He’d be tinkering.”

Graham left university and had success with a folding boat company, Quickboat. By the time his grandfather pulled out that vial of R327, he was already an angel investor.

The grandfather explained to him that it was a polymer – a large molecule made from smaller repeating molecules – that was soluble so it could get into the bloodstream. It would get into the bacterial cell via multiple entry points, disrupting metabolism and cell division, but would leave human cells alone.

“I love and respect my grandfather dearly, but as a person, he’s a ruthless warlord.”

James Graham

Graham didn’t need much pitching. “My Pop’s an incredibly dedicated person. When he says it has antibiotic properties, you better believe it because it will. With all the controversy and crap he’d dealt with, why would somebody want to go through that again unless they’re really, really sure it’s worth their time.”

For Graham, it was more a matter of figuring out what tests needed to be done to prove this thing worked, how much it would cost, and what it could pay.

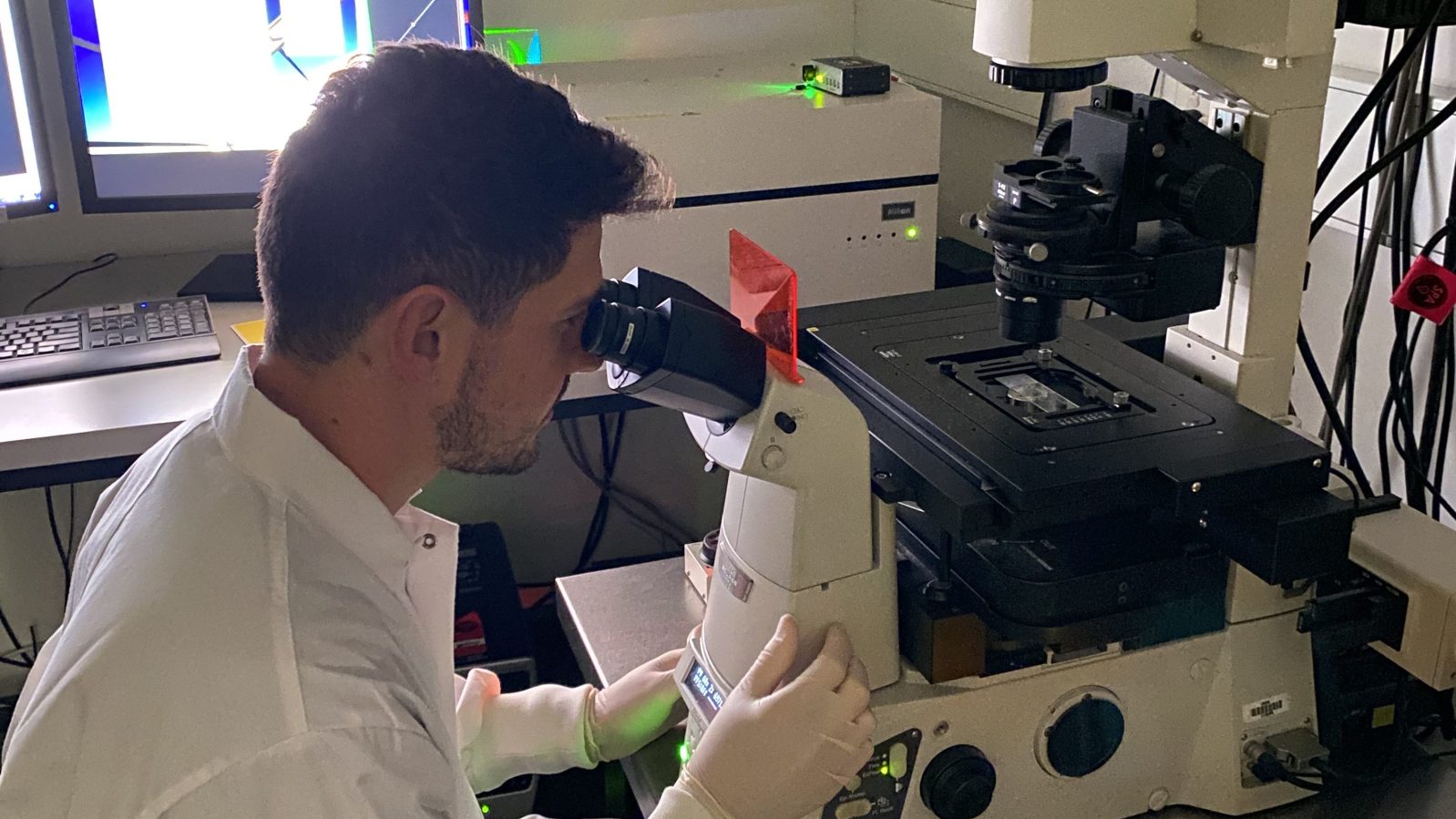

But his first job as executive director with the new company was lifting all the heavy testing equipment out of the garage and taking it in the back of his car to a small laboratory they’d secured in Bentley Technology Park in southern Perth.

Melrose had formed a company to utilise the government’s 43% R&D rebate on the $20,000 he’d already spent, and they spent more again doing early tests. “The one I found interesting was the ‘25-repeat test’, where it showed no loss of effectiveness after 25 doses,” says Graham. “Then there are the tests they don’t know you do, but you do do. I went down to the pet shop, got a whole lot of goldfish, and put them in water. You see how much [R327] you can put into that water before the fish start to get a little woozy. Because, when this stuff is passed from the body into the sewage system and the harbours, you want to make sure there’s no environmental impact. You take it to where the fish start just to tilt a little bit. We’re not out to hurt anything. It took mega concentrations.”

For the first three years, it was a part-time interest for Graham, securing investments from family and friends and “mates’ mates” till the register grew to 47 investors.

“In 2015, I hired myself, then we hired colleagues, put a board together, a prospectus, and we listed on the ASX in January of 2016.” Graham was executive director and his grandfather chief research officer.

By that time, they’d demonstrated safety and efficacy in animal studies. They had patents, and they’d shown the molecule was cheaper and faster to produce than traditional antibiotics. The polymer only has three ingredients, and they’re all cheap.

“We could compete on price with any other antibiotic in the market right now, including generics,” says Graham.

The IPO raised $5 million at 20c per share, valuing the company at about $14 million. The capital raised allowed them to step into the clinical realm. “We went from a few scientists mixing it in a beaker to fully automated.” The first humans to take it were in 2019, under the special-access scheme, “also known as ‘last resort’ dosing”.

Graham recalls the first patient. “They had a multi, multi-drug-resistant pseudomonas bacteria in their sinus. They’d been unresponsive to all existing antibiotics, to half a dozen surgeries. They had a PICC line [catheter] into their chest. They were on the way out. They were like, ‘I’ll do anything’. The clinicians have to assess the ethics and the potential for success. It was sprayed up into their sinuses, and a week later, the person was cured of their infection.”

The stock price soared over $1.60 in September 2020 during the early COVID-19 love affair with biotech. It’s been down and up – but mostly down – ever since.

“The antibiotic pipeline has never been drier while the need has never been greater.”

James Graham

With the price sitting around 50c, MST analyst Chris Kallos has a risk-adjusted price target on Recce of $2.46. However, Recce is a client, and he warns that such companies have risk profiles similar to mining explorers. And if they fail to jump through the regulatory hoops, everything can come to naught. “These things can be binary. But the fact they’ve got multiple indications underway gives some hope that something will hit the target.”

Graham is baffled by the market. “We got a $3-million grant [in July 2024] from the US Department of Defense for topical burn wound work – and the stock went down. The World Health Organisation (WHO), in its global antibiotic pipeline review, said we were clinically the most capable against what they considered the most deadly bugs – and the market barely moved. Whereas we’ll get a patent in some obscure country, and the stock goes nuts.”

While Graham has focussed on cracking the US – which comprises 48% of global antibiotic sales and where R327 has been granted a fast-track designation and 10 years of market exclusivity post-approval – an opportunity arose closer to home. “The Indonesian government knew the WHO was about to announce us as the most advanced new class of antibiotic, so they approached us,” says Graham.

Health Minister Budi Gunadi Sadikin agreed to expedite a Phase-3 trial in Indonesia. “We agreed if the results were compelling, it would get expedited approval for sale,” says Graham. “It’s a gateway to ASEAN. If you’re approved in Indonesia, you’re approved in Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam. There’s a total population of 680 million people.

“They have an 11% diabetes rate in Indonesia. If you have diabetes, 48% get a diabetic foot ulcer, if you don’t treat that infection – and there is no drug approved for it specifically – your foot will be amputated.”

The day after speaking to Forbes Australia in August, Graham was flying to Indonesia to discuss government subsidies for poorer people to access R327. Graham says even if it weren’t subsidised, in a country of 280 million, there was still a considerable market for Recce.

Only 300 people are being dosed in the Indonesian Phase-3 trial. “The coolest thing in this space is you don’t have all the costs and complications of other pharmaceuticals. Bacteria are really easy to identify. If colonisation is going down, it’s working. And if it’s going down in all of them, you don’t need many people to say you’ve got a statistically reliable result.”

Graham did not expect the Indonesian data to sway US regulators but was hoping Australian Phase-2 data would be enough to get a US Phase-3 trial going in the first half of 2025.

The trials are being broadened to treat a wider range of infections, including burns, sepsis [blood infection, for which Recce has an intravenous version] and, if Dr Wines has his way, bone infections [osteomyelitis].

If all goes well in Indonesia, Graham expects Recce R327 to be on the market by the end of 2025.

The global antibiotic market is worth $56 billion – growing at a whopping 10% in the diabetic foot ulcer and sepsis sectors.

“So your market is growing and the antibiotic pipeline has never been drier while the need has never been greater,” says Graham.

All this does bring a smile to his Pop’s face. Graham Melrose, now 90, retired from Recce in 2020 and lives in a Perth nursing home. He still owns about 20% of Recce.

“I love and respect my grandfather dearly, but as a person, he’s a ruthless warlord,” Graham laughs. “He’s a businessman to the core – that guy is an incredible person in so many ways; with deep authority and dictatorship-type tendencies. Christmas can be challenging if I haven’t met objectives!

“But yes, he does crack a smile. He’s absolutely supportive of what we do. I’ll speak to him every couple of weeks, and he’ll tell me in no uncertain terms what he thinks, and we act accordingly. I don’t always take on what he says, but we do work in a very harmonious way.”

A recce of R327’s milestones

| Date | Achievement |

|---|---|

| July 2023 | Phase I intravenous safety and tolerability study in 80 healthy human subjects. |

| February 2024 | MOU with Indonesia to facilitate late-stage clinical trials. |

| June 2024 | Phase II clinical trial into acute skin infections is broadened beyond diabetic foot ulcers. |

| June 2024 | Phase I/II intravenous urinary tract infection and sepsis clinical trial begins dosing. |

| July 2024 | Wins US$2m from US Department of Defense to create a gel for burns. |

| Q3 of 2024 | Start Phase II trial of intravenous treatment for urinary tract infection and sepsis in Australia. Starts Phase III trial on topical use with diabetic foot infection in Indonesia. Starts US Department of Defense burn-wound program. |

| Q4 of 2024 | Interim data due for the Phase II acute skin infection trial. |

| 2025 and beyond | Submit investigational new drug application to US Food & Drug Administration for R327. Completion of Phase III trial in Indonesia. Commence commercialisation in South-East Asia. |

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.