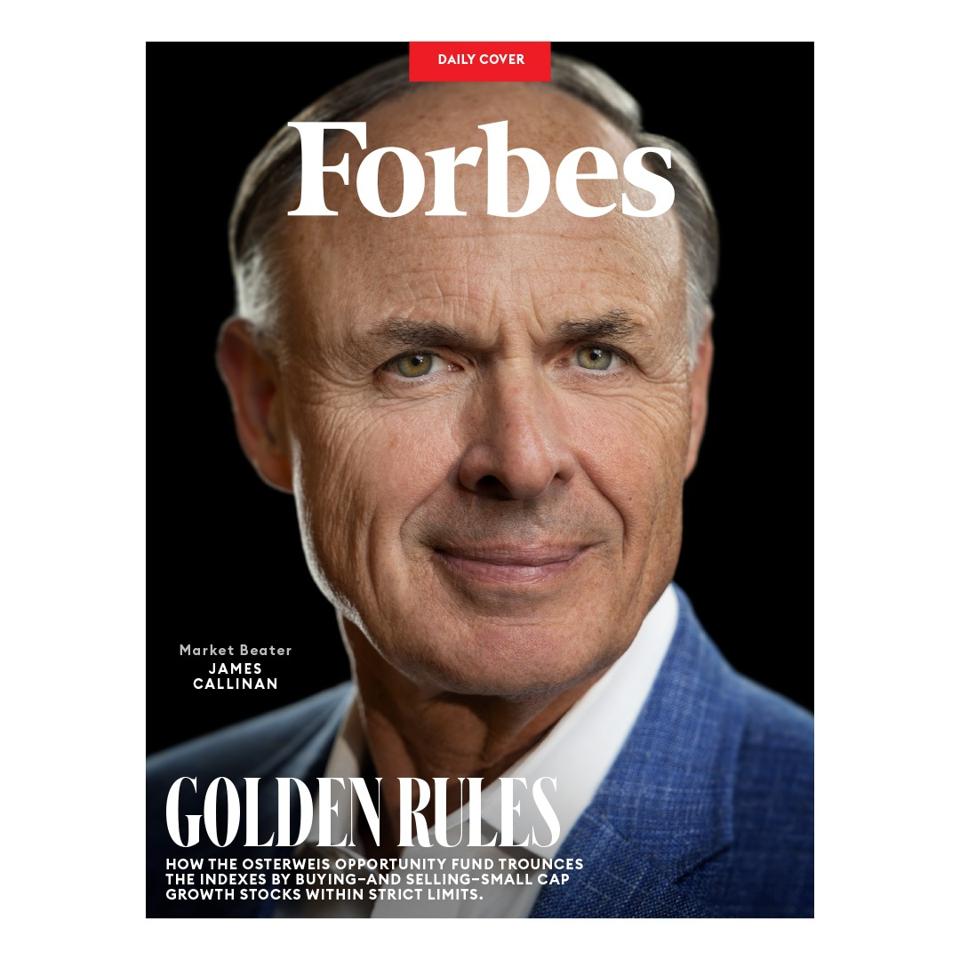

James Callinan’s Osterweis Opportunity Fund has trounced its Russell 2000 benchmark by applying specific P/E limits for buying–and holding–small cap growth stocks.

For most small-cap stock investors, 2024 has been yet another year to grumble about their chosen playground being ignored, even while trillion-dollar market-cap companies like Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft and Nvidia get ever more expensive. The Russell 2000 Index is still 14% below its November 2021 peak, while the S&P 500 has gained 15% in the same period.

The doldrums have pushed many small-cap portfolio managers to go hunting for deep value bargains. Not James Callinan—his $365 million Osterweis Opportunity Fund is winning with the formula he’s honed over nearly four decades: buy stocks with revenues and margins increasing faster than their peers, but do it with discipline.

“The small-cap indexes are filled with lousy companies,” says Callinan, age 64. “Forty-five percent of the companies in the Russell 2000 don’t make money. Another 20% of the index are non-growers. You probably only have around 20% of the Russell that’s even investable for the growth investor.”

Based in San Francisco, Callinan and his team make a living picking the right ones, and over the last 10 years, they’ve outperformed not only their peers but the S&P 500 as well. Osterweis posted a 13.2% 10-year annualized return through June, beating the S&P 500’s 10.8% annual return during that span and trouncing the 7.4% figure for its benchmark Russell 2000 Growth Index. So far this year, the fund’s 18.7% return after costs—currently 1.12% of assets—is among the best in its category, with the Russell 2000 Growth’s 4.4% gain lagging nine percentage points behind the S&P 500.

One of the keys to its success has been embedding strict valuation guardrails into its process despite its growth DNA. Before Callinan invests in any stock, he expects at least 100% upside over a five-year time horizon. But he has another hard and fast (and more unusual) rule—it can’t exceed an industry-specific price-to-earnings ratio to get to that doubling point.

For example, Callinan praises software as “the greatest industry in existence.” Yet he won’t buy a software stock that would have to rise to more than 30 times his team’s five-year earnings estimate in order to double. That cap is around 28 times for medical devices, while semiconductor capital equipment firms get a limit of 22 times earnings, and consumer stocks are confined to a multiple in the high teens.

If that sounds a bit complicated, the rule is actually pretty simple when you see it applied. If Callinan’s team estimates a software company will earn $5 per share in five years, he won’t pay more than $75 per share for that stock today, because its share price wouldn’t be able to double during that span without exceeding the 30x P/E cap.

Moreover, the rule isn’t a one and done exercise. It’s used on current holdings and often has helped the fund sell in time to stay out of trouble. In 2020, its best year, the fund gained 83%, fueled by the strength of stay-at-home stocks like Teladoc Health and digital health firm Livongo, which Teladoc acquired late that year. Spotting trends toward surging online traffic and ecommerce early, Osterweis started buying Teladoc in the first quarter of 2020. But after it tripled in value in the first seven months of the year, the fund could no longer justify the valuation. By the end of the third quarter, Osterweis had unloaded its whole stake, missing out on a 30% move higher into early 2021—and a 97% crash since then which has haunted holders like Cathie Wood’s Ark Invest.

“Once telemedicine became ubiquitous, it commoditized and everyone got into it. Covid was short-term good and long-term bad, so their competitive advantage went away,’’ says co-portfolio manager Matt Unger. “This was kind of an easy sell, especially considering how well it did.”

It’s a lesson Callinan learned through several market cycles before he started the current iteration of the fund. A Harvard alum who starred at running back for its football team and is enshrined in the school’s sports hall of fame, he received an offer to try out for the New York Giants in the spring of his senior year, but stuck with his job offer in consulting and auditing at Arthur Andersen instead. Three years there and two years back at Harvard Business School led him to Putnam Investments in Boston in 1987, where he was inspired by a seminal paper by Morgan Stanley’s director of research Dennis Sherva to zero in on emerging growth stocks.

In the mid-1990s, Callinan moved to San Francisco to work for Robertson Stephens Investments—just in time to live through both the inflation of the dotcom bubble and its epic bursting in March 2000. That led him to self-impose his valuation rules to mitigate risk. With few venture-backed growth companies going public in the 2000s, he created a fund with a concentrated portfolio in 2006, which is effectively the fund he still manages today after spinning out from RS Investments to go independent in 2012 and partnering in 2016 with Osterweis, a firm that offers three other mutual funds and now has $7.4 billion in assets. Unger, 38, left RS Investments to join Callinan’s team and Bryan Wong, 41, moved over from a separate Osterweis fund. Callinan named them both portfolio managers in 2021.

In the first half of this year, the Russell 2000 was propped up by a mere two stocks—data servers firm Super Micro (boosted by demand from artificial intelligence customers) and bitcoin and enterprise software play Microstrategy. Both grew so large that they graduated out of the index in June, though Super Micro has lost half its value since the start of July to trim its 2024 gains to 36%. Osterweis, despite its outperformance, owned neither. Overall, most of its portfolio is in health care, tech and consumer stocks that meet its limits.

“AI has the most long-term potential of almost any technology we’ve seen. I agree with that premise, but I also think we’re undergoing a little bit of a hype cycle,” says Wong. “There’s not a lot of AI revenue right now.”

Osterweis does have some AI exposure, including a stake in semiconductor servicing firm Onto Innovation, which is up 16% this year, though much of its outperformance is coming from its picks in other sectors. Two medical device companies in its portfolio, Shockwave and Axonics, were acquired by Johnson & Johnson and Boston Scientific this year at handsome premiums. Osterweis’ suite of healthcare stocks still includes Procept Biorobotics, which developed a minimally invasive way to treat enlarged prostates. Osterweis invested in the first quarter, and the stock has gained 55% since, buoyed by 74% sales growth in the last 12 months.

Fast casual salad chain Sweetgreen is another stock the fund bought in the first quarter, reaping most of the rewards of its share price tripling this year. After an expensive IPO in 2021, Sweetgreen’s stock fell 80% through the end of 2023 despite its sales continuing to grow, opening an opportunity to invest at a reasonable valuation. Wong compares its 225 locations to Chipotle’s 3,500 in citing its long runway for double-digit unit growth per year, and it’s beginning to roll out robotic kitchens that make salads more efficiently.

The result of the volatile moves these stocks make is high churn as Osterweis takes profits or reevaluates whether to set future earnings expectations higher when stocks hit their initial price targets. The fund turns over more than 100% a year, which Callinan sees as “a feature, not a bug,” if profits are realized fast enough to invest them into the next great opportunity.

“This is a category where you can make exponential-type returns on startup companies that are mysterious to a lot of investors,” says Callinan. “As companies come out of that mysteriousness into the light, it can really yield multi-bag returns.”

This article was originally published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.